Page Contents

(Art) confronts the livingdying going on. . . from within and letting the cry most compassionately come forth and move out – in all direction – wherever the human touches.

I

[I] walked by many times before I finally walked in on a rainy day in November. I needed a place to write a letter, and the shop looked convenient. My girlfriend at the time (now my wife), lived nearby and had been trying to get me to go into the shop since I arrived in Kyoto two years earlier. She thought I’d like the atmosphere and the homemade American icecream and cake. I wasn’t so sure. A small shop wedged in between many other shops lining Marutamachi Street, it looked worn and dusty. What attracted me was the name, painted in white letters on a faded blue awning in a flowing script resembling a Japanese brush painting. The letters formed a face, each “C” an eye with periods tucked into them, the “‘s” a nose. The coffee shop was dark and quiet the way my girlfriend had described it. I had just read Tanizaki Jun’ichiro’s book In Praise Of Shadows and was interested in the aesthetics he spoke of: “When we gaze into the darkness that gathers behind the crossbeam, around the flower vase, beneath the shelves, though we know perfectly well it is mere shadow, we are overcome with the feeling that in this small corner of the atmosphere there reigns complete and utter silence, that here in the darkness immutable tranquility holds sway.” Tanizaki would have loved this shop. Inside, a round paper shade softly diffused the room’s only light; the floor was made of stone, large uneven slabs of various sizes and shapes. The walls were covered with brown, finely-textured cloth. The furniture was of rough cut wood. Nothing shined. Even the silverware was worn to a dull finish.

After I sat down and ordered coffee and a slice of chocolate cheesecake, I noticed a few poems on the wall at the back of the shop, and I rose to take a closer look. I found three poems, two in English, the other in Japanese. The English ones were from the “On the Bus” series of poems that the San Francisco City government displays in city buses for the public. The poems were by Cid Corman and George Evans. As I was standing there, the baker came out to stand beside the register. “Do you know who Cid Corman is?” he asked. “Yes,” I said, slowly, surprised by the question.

I knew Corman was an American poet. I’d seen his poems around; I liked them and had bought two of his books of essays in a second-hand store in Seattle the year before. “He lives nearby and comes in often,” the baker continued, and handed me a slip of paper with Corman’s number on it. “You should give him a call; he’d like that. “

II

I first heard of Cid Corman when I was in high school; we were using Hayden Carruth’s anthology, The Voice that is Great Within Us. I found a few of his poems there; one poem in particular struck me:

There are things to be said. No doubt.

And in one way or another

they will be said. But to whom tell

the silences? With whom share them

now? For a moment the sky is

empty and then there was a bird.

This was in 1972, the end of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, Watergate on the horizon. We had witnessed the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King. It was a time of confusion and distrust. People argued and fought in the streets, in the courts, at home, and on campuses. Four students died at Kent State University protesting the war, victims of the times.

Out of the confusion and fighting, this voice comforted me: There are things to be said. No doubt. The poem acknowledged the use of language and its limitations at once, then went on to urge something more: the need to share our lives, the need to see what is before our eyes. By the time I finished reading the poem, I was standing in a new land with empty sky above me. I trusted the poem, and felt that if I listened to it hard enough I could clarify important issues in my life, issues as central as what I was going to do in my life, what I was going to live for. It worked on me like a Zen koan. I didn’t understand it, I liked it, puzzled over it, remembered it, lived with it for years. I recited it to friends at odd moments when I felt particularly lost for words, and they enjoyed it, began saying it back to me. The words rang and echoed.

I left the coffee shop thrilled to have Cid Corman’s phone number. I mentioned the encounter to a poet friend of mine, and he called Cid. We arranged to meet at my friend ‘s home. In that first meeting, we introduced ourselves, told each other where we came from, our histories, and what interests we had in poetry. I learned that Cid was from Boston, that his father and mother came from Russia, and that he had attended Boston Latin School, Tufts University, and the University of Michigan where he received the prestigious Hopwood Award in poetry in 1947. In short, I learned details about his life, the kind of details that allow people to get to know one another, that bring ease and friendship into a relationship. Cid was and is candid.

When he was in his mid-twenties, he started a poetry program on a Boston radio station, This is Poetry. The program ran for over three years and consisted of a fifteen-minute reading of modern verse on Saturday evenings at seven-thirty. The program featured such writers as John Crowe Ransom, Archibald MacLeish, Stephen Spender, John Ciardi, Theodore Roethke, Pierre Emmanuel, Allan Curnow, Richard Wilbur, Richard Eberhart, Katherine Hoskins, and Vincent Ferrini. A number of the programs were bilingual, in English and French, Spanish, German, or Italian.

This is Poetry led to some important meetings and contacts. For example, this is how Corman met Robert Creeley. Robert Creeley was in his twenties, and his work had not yet come into prominence. He heard the program and responded as many other listeners did: he wrote a letter. Cid wrote back immediately to invite Creeley to read on the program. Their meeting was a fortunate one for it would help bring a wave of new poetry into American letters. In 1951, partly to ensure that new poets, such as Robert Creeley could be read as well as heard, Cid founded Origin magazine. Robert Creeley would be a contributing force in getting the magazine off the ground, so too would be another influential early contact, Charles Olson.

Today Olson is thought by many to have been a grand American genius, in the spirit of Melville, Whitman, and Pound. A pioneer in American poetry, he pushed it into new territory, opening new ground. His seminal essay, Projective Verse, published in Poetry New York in 1951, detailed those intentions.

A poem is energy transferred from where the poet got it (he will have some several causations), by way of the poem itself to, all the way over to, the reader… the poem itself must, at all points, be a high energy-construct and, at all points, an energy-discharge. So: how is the poet to accomplish same energy, how is he, what is the process by which a poet gets in, at all points energy at least the equivalent of the energy which propelled him in the first place, yet an energy which is peculiar to verse alone and which will be, obviously, also different from the energy which the reader, because he is a third term, will take away?

This is the problem which any poet who departs from closed form is specially confronted by. And it involves a whole series of new recognitions. Prom the moment he ventures into FIELD COMPOSITION — puts himself in the open — he can go by no track other than the one the poem under hand declares, for itself. Thus he has to behave, and be instant by instant, aware …

Cid invited Olson to be a contributing editor for Origin. It is hard to know whether or not Olson welcomed the idea of being part of a magazine that would help bring out what he wanted to see in American poetry. Being an outsider, unassociated with any magazine or university, gave him certain freedoms he feared losing. Not knowing Corman well, Olson was suspicious of his intentions. He fired a letter back to Corman to clarify his position. Tom Clark, in his biography of Olson, The Allegory of a Poet’s Life (Norton, 1991), gives an interesting account of this reply:

Olson wasted no time on preliminary courtesies, snowing the would-be editor under an extended set of directives thrust forward with a mixture of dictatorial bluff and generous conjecture. To start with, Corman was put on notice he would have some adjusting to do. When he reported attempts to negotiate subsidy for the magazine from Brandeis University, it was suggested by Olson that he was dangerously soft on academia. And when Corman confessed to harboring certain residual sympathies for the middle-of-the-road poets of the day, Olson sniffed at the idea of colluding in the creation of just another predictable forum for the “well-made poems” of such “decidedly impressive” contemporaries as “o, say Harvey Shapiro, or Richard Wilbur… or, Stephen Spender (intimate) or who[ever] else … you think of publishing.”

Olson knew what he wanted the magazine to be, but did it fit with what Corman wanted it to be? Corman and Olson corresponded for years. Both dialogic and dialectic, their letters were passionate, argumentative and tough. [Charles Olson and Cid Corman: Complete Correspondence 1950-1964, Vol. I, ed. George Evans (Orono: National Poetry Foundation, University of Maine, 1987) ]. They detail the emergence of a “new push,” to use Olson’s epithet, in American poetry, a push that Origin and Corman would help bring into existence and further. The poems of Charles Olson and Robert Creeley were featured in Origin Vol. 1 and Vol. 2. Wallace Stevens was featured in Vol. 3, with one of the first detailed essays on Steven’s work.

Cid edited and published Origin for the next 30 years, a difficult task as he had little if any financial backing. Despite many hardships, the magazine succeeded in publishing some of the best new poets writing in English from around the world, poets as fine as Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Louis Zukofsky, Larry Eigner, William Bronk, Lorine Niedecker, George Oppen, and Gary Snyder, to name only a few.

I was thrilled to be in the presence of someone who knew so much about poetry, a linking figure in postmodern American poetry. Here was a poet who could tell stories of visiting William Carlos Williams’ house at 9 Rutherford Street and having Williams ask him to read Asphodel, that Greeny Flower when it was in draft. A man who could tell you stories about Zukofsky, Oppen, Goodman from first hand experience, from years of correspondence and friendship. What Corman had to say was unobtainable in books; it was a private storehouse. I marveled at his wealth of experience, his knowledge, and wondered why I hadn’t heard more of him when I was in the U.S. Why hadn’t I heard anything of him in the universities where I studied literature and creative writing?

In the late fifties, Cid was awarded a Fulbright scholarship, recommended by Marianne Moore, and set off for France. He lived there for seven years and began translating Celan, Char, and Ponge. He was the first to translate Celan into English, begging Celan to allow him to do so. Celan did not want his work translated and refused to consent. Corman went ahead anyway, even under threat of litigation. He believed that strongly in the value of the work.

After his stay in France, Cid went to Italy where he was promised an English teaching job that would allow him time to write, working for the U.S. Foreign Service in a small mining town called Matera. It was an impoverished community, but a community with vitality, rich in culture and history. The poetry of Sun Rock Man (Origin, 1962) is infused with the spirit and life of this place:

The labors

Men work. Usually

hardly at all. In the hills

they lazy about in gangs,

let machines grind rock to gravel.

In tandem, but freely,

they shovel buckets full and

heave them up to the shoulder

and up into the truck beside.

Slowly rock is eaten

away. Slowly the men eat

up the day. Slowly the day

dies. The truck pulls out. Rock remains.

On a ridge above them

a shepherd crowding some grass

lets his flock browse corralled by

only a barking bounding dog.

Beyond them clouds go on

covering sky. Somewhere the

sun descends. And dog sheep men

rock hills collect between them night.

In 1963, Cid arrived in Japan almost by accident. He had applied for 27 teaching jobs in Asia, 26 of them outside Japan. As luck, or fate, would have it, he was offered the job in Japan. Since then, excepting a short stay in the U.S. in the eighties, Cid remained in Japan, returning to the U.S. only rarely for visits and readings. He married in 1963, and together he and his wife, Shizumi, founded C.C.’s, the coffee shop I walked into that rainy day in November. After running the shop for over twenty years, Cid and Shizumi sold it to Shizumi’s brother.

What has Cid been doing in Japan these thirty plus years? Poetry. And more. He has worked as editor, translator, and critic. He has published over a hundred books, and seen Origin through five series, one series comprising twenty issues. His translations of Japanese poetry, notably Basho’s Back Roads To Far Towns, (Tokyo, Mushinsha, 1968), Kusano Shimpei’s frog poems, Frogs and Others: Poems by Shimpei Kusano (Tokyo, Mushinsha, 1968; New York, Grossman, 1969), and more recently Santoka’s haiku, Walking Into the Wind, (San Francisco, Cadmus, 1990) benefit from Cid’s first hand knowledge of Japan, its culture and language. Both Sam Hamill and Donald Keene, exceptional translators of Japanese literature, have recommended Corman’s translation of Basho, Hamill calling it “essential reading.” I met with Cid every other Sunday for the next few years. The meetings lasted 5 to 6 hours. The group grew to four, sometimes five members. Cid came to the house with a worn satchel bursting with books; the zipper broken. He began by reading poetry, a short story, an essay, or a letter. This sparked conversations that could go anywhere. Once, he began by reading The Wreck of the Deutschland and had us discussing Hopkins, Rilke, Holderlin, Goethe, Catholicism, Picasso, Zukofsky, the history of both World Wars, and sumo wrestling, all in one afternoon. The meetings were thrilling, and Corman’s breadth of knowledge daunting.

When I gave him one of my poems to look at, he screwed his eyes down and leaned into it. He warned me he would tell the truth. He told me that when it came to poetry and talking about it he had been told he had bad manners. I welcomed his seriousness. He cut into the poem with intense honesty, intense passion. The soft-spoken poet disappeared; he became the editor. He wanted every word to function fully, with the language worked hard. “Your whole life has got to be on the line, and it’s got to be a hot line.”

When looking over a poem or speaking about poetry, Cid has opinions and holds to them, remaining open to others’ opinions, provided they speak when he is finished. On more than a few occasions, I wanted to crawl away after a session and not show another thing to him until I was sure it was as good as it could be. Cid doesn’t see himself as a teacher and no one sharing their poetry with him should be confused on that point. Cid is an editor, and he has experience. He tells you the way he sees it, bad manners and all. No doubt, sometimes he may be wrong. More often though, you know he’s right.

For me, Cid has been a source of moral support. He is the seventy-year-old poet telling me it is worth it, telling me it is tough, telling me he’s spent a lifetime doing it. He has little money or fame to show for all his years, but he has the poetry and a life rich in it. He has been the elder who has responded to every postcard, letter, or phone call. The man never too busy to listen and offer help. Typical of his generous spirit are the excerpts below, taken from his letters to me:

Talent? Every one has unique talent/s. BUT I have had long experience with wdbe poets and have seen to my surprise and chagrin early on that talent alone accomplishes little and often – badly used – deteriorates into slick shit On the other hand, I have seen quite a few people – men and women – with very modest gift by sheer persistence find their way into poetry – quite incredibly.

You have to be painfully ruthlessly honest with yourself (even more than with others – where tact has some place – tho as you will have long since noticed – I have little of it).

I had been questioning whether I had enough talent to warrant a life in poetry. Corman’s response was encouraging, though tough. In this, it was characteristic of him. Another excerpt:

Life is the music – Greg – and your life your music. No one can take it from you – or give it to you (beyond those who did) -but you may need time to hear it or let it come through. It happens when you are moved beyond yourself into the open. It requires an honesty with oneself that is always rare – and often when you think your ARE being honest – you are deceiving (kidding) yourself most. It needs a terrible ruthlessness.

It isn’t a matter of sounding good but of being good – living each word in its fullness as they OCCUR. Not to get ahead of yourself but not to fall behind either. It WILL come, if you have the staying power. And even if you fail – it may still feed richly into your life.

Ego – despite all the accent put upon it – isn’t the issue. But how to share life with others and in a way that makes it even yet (in the face of what we all face) possible. Given what it is -for any of us – there’s nothing to get hoity-toity about.

We’re all small potatoes – Nobelists and Presidents, Kings/Queens and Champions.

Why should what you feel or have felt be of any interest or concern to ANYONE ELSE?

And how can it be unless you open to others to core? This is hard to do. We hide from ourselves as well as others.

The poem you want to write maybe will not come clear to you till within moments of your death. That’s the way it goes.

There’s no sense praying that I suffer no more sorrows. It comes with the territory. There is nothing to pray for – as my poems try to make clear. If life means anything to anyone it means precisely life and living this very moment aware of it and how it is shared – generously – magnanimously – tenderly.

Your a good guy – unmistakably, but you will have to suffer for it and from the suffering (without looking for it) you will find such depth of joy that every single moment offers.

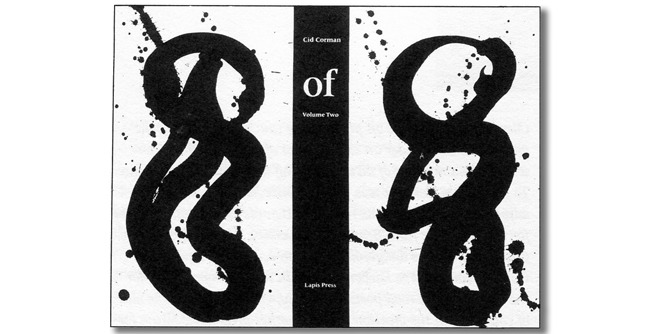

Presently, Cid is writing and putting together a large book entitled OF. The first two volumes were published in 1992 by Lapis Press, a beautiful boxed edition with jacket art by the American painter Sam Francis. Three volumes remain to be published. When it is completed, it will be, “in 5 vols. – each about 750 pp.” It will be “ONE book, very carefully edited (7 years in editing) (decades in writing), not a collected or selected job. “

When the first two volumes of OF were published, they received little critical attention, two reviews: one in a small mimeo magazine and the other in Arts Magazine (New York), a magazine one would expect to be more concerned with the book’s design than with the poetry. The review did however, praise the poetry, calling Corman “the best kept secret in American poetry.”

I puzzled over that comment, intrigued by it. How could a man so involved in shaping American poetry over the last 50 years be a “kept secret?” The comment raised questions about his life, work, and poetry. I wrote to Cid to inquire.

III

An Exchange of Postcards

OF received only two reviews in the United States, and in one of those reviews, you were said to be one of American poetry’s best kept secrets. How do you feel about being referred to in this way? Is there anything you would do to change that? Do you mind being viewed as a secret?

There are plenty of people who know of my work. The work is there – over 100 books – over a period of 40 years! And most libraries have something. Sadness is that I believe the work speaks more clearly to ALL than any other poetry of our time. And speaks to root matter. Most of my books have never had ANY notice. Fact.

Does this make you bitter? Does it disappoint you?

What I say above is simple truth but there is not bitterness here — only sadness. Since the work is not done for fame or money -but only for others.

1 have no bitterness (have gone out of my way and lost friends sometimes because of it) to avoid publicity. Not because I have anything to hide – the most shameful things in my life are openly found in my work. Simply: the work is my life – my life the poetry. If you turn to them you have all of me that anyone cd want -1 trust it will be of some kind use in the difficulty of being anyone -or all.

Could you say more about “All” and “root matter,” how do you mean the work speaks to them?

My poems invariably address themselves to people of all ages, creeds, countries, and times (even the dead) & invariably probe human nature to the root (to the ground of being it comes from).

You’ve said it is important to be heard as a writer. How do you balance that need, desire, with writing itself? I mean, how important is it to be heard in comparison with the writing itself?

Writing and being heard go together. I’m not writing for myself, all work meant to bring others to face the fact/act of being.

How patient should a young writer be about being heard, published?

As patient as his or her feeling for the word of living/dying being offers.

How much self promotion of one’s work should one do? What dangers should one be aware of, careful of?

Self-promotion? The work has to speak for itself, always, and you send it where you think it may be heard.

You have said that you wouldn’t give an interview unless it dealt specifically with your work. Do you still feel that way? Why?

Interviews I dislike. They make one too important. Let the work speak for itself and in quiet moment/scale.

Though you dislike interviews, you are always receptive to people who are interested in poetry. You invite them to your home and give generously of your time. How would you say such an interaction differs from the interview? What interests you in it, about it?

An interview is a publicity deal. Always has been. Part of journalism. It has nothing to do with poetry. Where are the interviews with Homer, Sappho, Tu Fu, Li Po, Shakespeare, or Blake? Who needs them? In the early 50’s when WCW and Floss took me into their house like one of their sons -1 learned decisively to want to share such cordiality in my own life – to the extent I could. To share life is what life is all about.

You receive letters from around the world. Younger poets find your work, are drawn to it, and contact you. What do you think it is that draws these young writers to you?

Some youngers find me somehow – often by accident. My work is clear and tends, I think, to make an immediate impression or none at all. Too direct for some, perhaps.

Do you respond to all the letters you receive?

Invariably. And at once. As long as they clearly want response.

What is the most surprising thing that has happened to you through your correspondence in letters? Is there anything that stands out as remarkable?

Everything. Every letter is my news. Is poetry.

You’ve been working through the mail this way for years -this exchange of postcards for example, this interview. What role does correspondence play in the world of your poetry?

As you know – I live at a distance, as it happens, from most of my poetry coevals. Any mail becomes a life-line.

Why have you remained in Japan all these years? What attracts you? How has the experience of being in Japan affected your work?

Above all – Shizumi wants to live here. Does that make any sense to you? And I have lived in Kyoto over 30 years: have you ever lived that long in any one place? Try it – Then you will find my answer for me. Japan is home: how does home affect anyone?

Yes, that makes sense to me. I have been in Japan, on and off, eight years and I am married to a Japanese woman. I feel reasonably at home here. I guess what I was trying to get at was how the culture itself might affect you, might affect your work. You have spoken in your work of silence and of having places in our lives where we might inhabit the silences, share them even. You have spoken in some of your essays about the American culture’s near distrust of silence. Could you say something about what aspects of Japanese culture you have felt yourself attracted to and why?

All cultures (peoples/histories) stories interest me. Kyoto is a good city for a poet to work in. Relatively quiet – the largest village in the world. The Japanese have a deep interest in poetry – even if they don’t read it much. It is a natural (now) part of their lives. This may not remain so – but during my lifetime it will.

One last question. You have sometimes said that it is very hard to write poetry these days because there are so many temptations leading the other way. Could you explain more what you mean by temptations, what you see them as?

Temptations? The life of poetry is – as it happens – reliably ascetic (unless like James Merrill or Robert Duncan etc. you happen to be born or brought into money / ease). You can answer this better than I can. Money, family needs, nice things, health problems, etc. All these can and do deflect I And there are no guarantees of “success” (whatever that means).

Cid Corman is probably the most precise and clear poet alive. His clarity is what makes him so mysteriously alive… Further experience in the rhythm of the language and also in the real precision of diction, and in the precision of rhythm were being carried on by people like Cid Corman, wonderful poet, very neglected.

—James Wright, Collected Prose

Cid Corman’s work is familiar to some in the U. S., but is not well or widely known. A kept secret. American poetry cannot afford to allow Corman to remain a kept secret. If that sounds presumptuous, I’m among a long list of people who have spoken for the quality and interest of Corman’s work over many years, among them: Denise Levertov, Hayden Carruth, Hugh Kenner, Louis Zukofsky, Basil Bunting, John Ciardi, and Clayton Eshelman. This said, one wonders why his work has not received wider attention, at least enough to prevent him from being referred to as a “kept secret.”

Several years ago, I met Cid in the coffee shop after visiting a Zen temple in the mountains outside of Kyoto. I’d been up at the temple for a week, participating in a retreat, a seshin. While there, I saw a brush painting that I thought Cid would have liked. In translation, it read, Gain is Illusion, Loss is Enlightenment. When I mentioned it to him, however, he showed little interest. He told me in a tired voice “Of course, but the thing is you know, it’s got to be lived, the thing has got be lived.”

Riding home on the bus, going over that afternoon’s discussion in my mind, I hit upon the similarities between that sign and the first poem I’d seen of Cid’s. Both sign and poem talked about loss, the sign directly, the poem less so. In the poem, the speaker addressed the question of what can be said, knowing life is made up of the distance between “is” and “was:” … For a moment the sky is/empty and then there was a bird. In other words, life is coming and going, and we know it, feel it. We want to say something to this condition, about it, but what can we say? What will we say? The poem begins: There are things to be said. No doubt./And in one way or another/they will be said. But to whom tell / the silences?….

The moments in our lives when we come to see the reality of this condition of loss, are to be taken, I believe, as “the silences.” They come casually as when we look at blossoms falling from a tree, or tragically as when we lose a loved one. Whatever the case, we are rendered silent by the experience in so far as we are unable to offer any explanation for it. Who can explain why there is loss, why there is dying, any more readily than he can explain why there is life, why there is living? The explanation remains out of bounds, unspeakable, of silence. The poem probes into the question: how are we to live, knowing loss is the central condition of our lives?

Corman’s poem says Gain is Illusion, Loss is Enlightenment. The bird comes and the bird goes, and in the intervening time something has been quieted and learned. It is an enlightenment of sorts, and it comes through loss. Rather than saying something definitive, something gain-sayable, the poem directs us away from words to no words, to silence. It invites us to pause here, leaves us looking up at an empty sky where a bird once was. We are forced to encounter this loss and consequently the realization that follows, the awareness of reality in its striking beauty and mystery:

Did I have to come

to Iowa to

meet the world — greet all

of human being

in the name of word?

We speak in the night

cicadas deafen

and crickets work through

making as much of

what they are as we

to keep going. Come

to Iowa too

nameless to nameless

of no account and

perfectly attuned.

In their namelessness the cicadas, crickets and speaker are “perfectly attuned.” Animals: they live a short time, sing a brief song, die. Referred to in the poem is the Iowa of The Iowa Writing Program, the premier graduate writing program in the United States. Corman had been invited to read and teach there. Though honored to have been invited, presumably, he guards against the honor going to his head. He maintains a life founded in knowing nameless-

The point is

not ourselves,

not me – nor –

as it turns

out – you. Then –

we ask – Who?

No who, no

what, no known,

and nothing

to be known.

No point. And

none in this.

And never

the less, this.

Speak to man.

This is not a pessimistic view, but a sane and gracious view. We need each other. It is knowing loss that actually prope Is us towards the other. This reaching for another is the meaning of greatest significance to Corman. He asks nothing in return, no gain: “No who, no/what, no known,/and nothing//to be known.” He helps us see the clear condition of our lives and how that condition unites us, brings us together, and provides a compassionate place for us to begin to speak our urgent words to each other.

Up against it

at the very

edge, knowing it

will give or has

been given on

no other terms

than this. Not a

matter of life

or death. But of

life and death. In-

stead of a gun

I reach for you.

Corman has been living Gain is Illusion, Loss is Enlightenment for a long time, and knows how difficult it is to keep your eyes open that way. He is a man who has never, to my knowledge, sought gain. He lives today in the neighborhood of, if not in, poverty. He writes poetry, gets by on little. The life that has come to him through poetry is what he lives, nothing more and nothing less. He accepts the difficult condition of not having money enough to buy new glasses, fix his teeth, fly home to see a dying brother. “It must be lived.” Tough as his life is in material terms, Corman is a loving, joyous, and generous man. His poetry shows this.

Corman’s most recent books are [as of 1996]: how now (Spike/Cityful Press, Boulder, Colorado, 1995), a “transvising” of the Tao Te Ching; Walking Into the Wind, a Sweep of Poems by Santoka, versions by Cid Corman (Cadmus Editions, San Francisco, 1993); OF (Lapis Press, Venice, California, 1992), a beautiful, 2 volume boxed edition mentioned herein; Where Were We Now (Broken Moon Press, Seattle, 1991) a collection of essays. These books, older books, and volumes of Origin magazine can be obtained through Longhouse Book Company, Jacksonville Stage, Green River, Brattleboro, Vermont 05301 (c/o Bob Arnold).