[D]read clouded the joy that surged in Tomé’s heart when she heard the voice call out “Obachan, I’m back.” In May, 1945, the only pilots who came to Chiran were volunteers for the Special Attack Corps, boys who rammed their fighters into the American ships off Okinawa. Tomé dried her hands on her apron and walked out the kitchen. Lieutenant Mitsuyama stood inside the restaurant, his figure dark against the glare from the glass doors. “I won’t be here long this time, Obachan,” he said. Eighteen months had passed since she saw him last, when the airfield in Chiran was an Army Air Corps flight school and the pilots, just boys, had crowded into her restaurant.

They called her Obachan, “little mother,” a pet name, full of affection, reserved for older women. Forty-one, a bus driver’s wife with two daughters, Tomé looked after the boys as if they were her own. Lt. Mitsuyama, quiet and gentle, was one of her favorites. While the other boys sang and boasted and cuffed each other, Lt. Mitsuyama stretched out on the grassy banks of the brook flowing behind the restaurant. Sometimes he and Tomé’s daughters, Miako and Reiko, took long walks along the Fumotogawa River. The day he told Tomé he was a Korean, she understood why he kept to himself. After Japan colonized Korea in 1910, all Koreans became Japanese citizens—and suffered brutal discrimination from their subjugators. Lt. Mitsuyama’s parents brought him to Japan when he was a child. The war started, and Lt. Mitsuyama enlisted in the Army Air Corps. Now he was here to die. Tomé tried to find her voice. “I’m happy to see you again, Lieutenant,” she said.

He came to Tomé’s every day and lay beneath the trees, staring into the light that patched the leaves. On the evening of May 10 he told Tomé he was leaving at dawn. “We’ll miss you,” Tomé said. She called Miako and Reiko to come say goodbye. “Obachan, may I sing a song?” he asked. Tomé was surprised, but pleased. She knelt on the tatami next to her daughters.

Arirang, Arirang, Arariyo

Now that you have left me

And gone over the pass of Arirang….

It was a Korean folksong. Tomé and her daughters sang along, struggling to stifle their grief. When he finished, Lt. Mitsuyama handed Tomé his empty wallet. “It’s all I have,” he smiled. He walked into the night. He never returned.

Tomé sat down to write the letter to Lt. Mitsuyama’s parents. Sometimes the boys were only there for a day, sometimes for a week, but she always wrote to their parents: “My name is Torihama Tomé and I run a small restaurant here in Chiran and I had the honor of knowing your son and I would like to tell you how he spent his last….” She wrote quickly, holding her head away from the paper so her tears didn’t make the ink run. But she didn’t have Lt. Mitsuyama’s address. She looked through the wallet and asked the boys and the senior officers, but nobody knew. The war ended, but Tomé, hoping her memory of Lt. Mitsuyama’s last night would bring his parents peace, kept searching until the end of her life. She never found them.

Tomé came to Chiran, a small town on the southern tip of Kyushu, with her husband, Yoshitoshi, in 1922. Twenty and attractive, she blushed when a kimono manufacturer asked her to model for a series of advertisements. She took the job; they needed the money. Miako was born in 1926; Reiko in 1930, a year after Tomé opened her restaurant. The first “red dragonfly” trainer landed at the airfield in Chiran in 1941, three days after Pearl Harbor. When the flight school commander asked Chiran’s chief of police what the best restaurant in town was, the chief scratched his head and said he didn’t know, but the friendliest was Torihama Tomé’s. The next day a sign hung from Tomé’s doors: Military Designated Restaurant.

The pilots, some as young as fourteen, staggered into Tomé’s on Sundays. Homesick, exhausted from the training, they slumped behind the tables. Many had never been in a restaurant before. Tomé slung a towel over her shoulder. “Well, what do you want?” she asked. Excuse me, Torihama-san, it’s not on the menu, but could you make this? My mother used to make it for me. “I’ll see what I can do,” Tomé said. But Torihama-san, I don’t have any money. Tomé laughed. “Men don’t talk about money,” she said, and disappeared into the kitchen. The boys ducked their heads and grinned. She called us men. Tomé brought their orders. “Well, how is it, then?” she asked. Good, they said, better than my mother’s. “Don’t say that,” Tomé said, “just ‘good’ is fine.” She started toward the kitchen. “Obachan?” Was the boy talking to her? “Thank you, Obachan.” Tomé stopped. You’re welcome, she said. “Obachan?” another boy called. “Can you make this?” I’ll try, she said. “Obachan?” another boy called out. “Obachan?” You wait your turn, now, she said, and laughed.

When the boys’ training finished they came to say goodbye. “Obachan, thank you for everything. You were more than a mother to me.” What could she say? The boys almost never got a chance to say good-bye to their real mothers. “You be careful up there,” Tomé told them. We will, the boys grinned, and saluted. They lifted their Hayabusa fighters off the ground and dipped the wings in farewell before disappearing behind the clouds. Tomé knew some of them died in the sky, but she never knew who or where. When the new boys came and asked if Tomé could make the food their mothers had made, she pushed her worries behind her and smiled and said she’d see what she could do.

On a Wednesday morning in the spring of 1943, Tomé woke with a pain in her right side. It’ll pass, she thought. But the pain didn’t let her sleep that night. The next morning Reiko was surprised to see a car tearing up the road to the farm where she and her classmates were pulling potatoes from the fields. The war had drained the country of men; girls spent most of their school days on farms. Reiko’s teacher ran up. “Your mother’s been taken to the hospital in Kaseda,” she panted.

Miako was sitting on a bench in the corridor, staring at her folded hands. Reiko sat down. “Mother’s appendix has burst,” Miako said, “and peritonitis has set in. The doctors say she probably won’t make it through the night.” Their father was huddling with relatives at the far end of the corridor. The words “plans for the funeral” floated into Reiko’s ear. The doctors packed Tomé’s abdomen in ice to kill the infection. Two days later the fever fell and Tomé opened her eyes. The doctors called it a miracle. Another six months and Tomé left the hospital. “God didn’t take me,” she told Reiko, “because there’s something left for me to do.” 1944 was two months away.

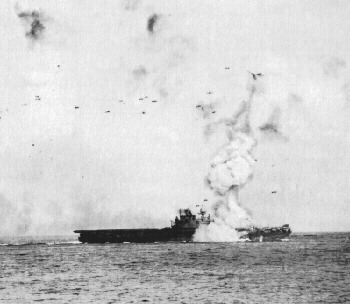

On July 9, 1944, after nearly a month of fighting, Saipan fell. Twenty-seven thousand Japanese troops were killed; the Americans lost 3,116. In Guam, 1,744 Americans laid down their lives; 18,250 Japanese died. The lopsided numbers followed the Americans island after island, while British, Australian, and Chinese troops mauled the Japanese in Asia. B-29 bombers took off from Saipan and dragged thick lines of bombs through the neighborhoods of Tokyo. In March, 1945, Allied ships and planes rained a half millionshells and rockets on Okinawa to soften the island for their assault. Desperate, the Japanese high command turned their eyes to the heavens: The winds of the gods had saved Japan from invaders in the thirteenth century; maybe the gods would intercede again.

The pilots lived in the forest, in half-buried huts hidden beneath branches and grass. Their camouflaged planes, loaded with explosives, waited nearby. “I’m sorry you’re missing school for us,” a boy told Reiko. Reiko said they were proud to help. “I’m glad,” he said. “Don’t worry. Once we destroy the American ships, Japan will win and you can go back to school.” Thank you, Reiko said, and bowed.

The boys went to Tomé’s at night and drank and smoked and wrapped their arms around each other’s shoulders and sang:

You and I, blossoms on the same branch,

Have bloomed in the garden of the Air Corps.

Once a flower blooms,

It knows it must fall.

So, come let us fall,

For the glory of our country.

Tomé put her arms around them and sang too, feeling the life in the heat of their bodies and in the rise and fall of their lungs against her chest, and although she tried not to cry, tears burned her eyes.

In the beginning the pilots died in a flurry of flames and cherry blossoms. Pink clouds billowed from the gnarled branches of the cherry trees in Chiran at the end of March.In the purple darkness before dawn, Reiko and her classmates snapped off the branches where the flowers clustered the thickest and scurried to the airfield, hugging the branches to keep the petals from flying.

While the ground crew dragged the tarps off the planes, the boys puffed on their last cigarettes and toasted each other with saké cups filled with water to symbolize their vow—they would never return. The girls dashed up and the boys took the blossoms and thanked them and turned to their planes. Sometimes the boys’ parents came to say good-bye. The army drove them to the airfield in trucks. They had time for a handshake, a few words, a last bow. “Obachan, sayonara!” the boys shouted to Tomé above the sound of the engines hacking into life. “Sayonara,” Tomé called back. She bowed deeply to hide her tears.

The girls waved and smiled and shouted sayonara, sayonara while the boys slid the canopies over their heads and pulled their goggles down.The engines snorted oily plumes of smoke and the blast from the propellers flattened the grass. The fighters circled around to the north and pitched their noses low and screamed back over the airfield, wings rocking in farewell. Tomé often tried to follow a favorite boy’s plane as it roared overhead, but there were so many, and they all looked the same. The girls waved until the fighters speckled the dawn sky.

The American ships were ninety minutes away. The girls crowded around the entrance to the radio hut. Any word from Lieutenant Kimura? “Nothing,” the operator said. How about Sergeant Suzuki? “He said he was going in, then his radio went dead.” After static shredded the last boy’s voice, the girls stumbled deep into the woods where they couldn’t be seen. Then they cried. There were no incense sticks for prayers, so they pushed up mounds of dirt and stuck the dead boys’ cigarettes on top and murmured into the strings of smoke.

Lieutenant Fujii kept to himself. Tomé tried to reach out, but the way he hefted his solitude shied her away. Lieutenant Fujii had lived near Tokyo, close to the high banks of a river, swift and deep, called the Arakawa. He had two baby daughters and a wife who saw further into his heart than he ever could.

At the start of the war, he trained boys to be pilots. Near the end, he heard where his boys were going. “It’s not right,” he grumbled, “that they should die and I should live.” He volunteered for the Special Attack Corps. The army turned him down. A wife and children. Too old. After his second transfer request was rejected he wrote the third in blood. His wife watched him from the hall. Before dawn on December 15, 1944, she left a note: “We’ll be waiting for you.”

She bundled her daughters to her chest. Frost crackled under her feet. At the edge of the bank she cupped her babies’ heads in her hands and threw herself into the Arakawa. His family gone, the army relented. Lieutenant Fujii led a squadron out on May 28, 1945. They never returned.

Tomé’s military designation got her rice, flour, and other staples, but the boys wanted more. “Obachan, I’d sure like to eat daifuku one more time.” “Obachan, if you can, shiítake would taste good now.” Cash was worthless; the men who rattled the doors late at night came to trade, not to sell. What did Tomé have? Reiko watched things disappear from the house. “Those boys are dying for our country, for us,” Tomé said. “Can’t we do this for them?” Tomé’s kimonos, which she got for modeling so many years ago, were the last to go. She never told the boys. “Here’s your daifuku,” she said. “Shiítake? Let’s see what I can do,” she said.

On a Thursday morning late in May, while Tomé was pulling open the restaurant’s doors, the front door of the Uchimura Hotel across the street creaked open. A couple, about Tomé’s age, dressed in the same kind of drab monpé she wore, bowed to Mrs. Uchimura and walked down the street toward the airfield. “Lt. Nanbu is their only child,” Mrs. Uchimura told her later. “They’ve come to say good-bye.” That afternoon, Tomé watched the couple shuffle back into the hotel. He must be leaving tomorrow, Tomé thought.

The next morning an army truck rolled up to the hotel at five-thirty. More than a dozen people from town, all in monpé, were going to the airfield to say good-bye. Tomé and Miako hopped up onto the bed. Lt. Nanbu’s parents were sitting just behind the gate. Lt. Nanbu’s father wore a gray hakama, and his wife was dressed in a formal kimono, so white it glowed in the darkness. Tomé was surprised to see the handle of a white parasol curling over his wife’s fingers. Why did she bring the parasol? The sun wouldn’t climb high into the sky for hours. As the truck rattled toward the field, Tomé’s astonishment turned to understanding, and then to grief: Once in the air Lt. Nanbu could pick his mother out of the crowd. But over seventy fighters were leaving that day—his mother wouldn’t know which plane bore her son.

At the airfield Lt. Nanbu cut through the lines of pilots streaming toward their planes and stretched out his hand. His father took it. Tomé watched the men’s lips move, their hands fall. Lt. Nanbu’s mother bowed. Her son saluted. They spoke less than a minute. Lt. Nanbu started toward his mother, but stopped. He saluted and fell in step with his comrades.

As line after line of the planes turned and howled back over the field, Tomé’s heart grew heavier—she knew the futility Lt. Nanbu’s mother must be feeling. Suddenly, a red streamer whipped out from a Hayabusa just coming out of its turn. As Tomé, astonished, watched, the streamer flapped twice and snapped taut behind the fighter. Tome heard a whoosh behind her. It was Lt. Nanbu’s mother. She had opened the parasol and was waving it above her head. Lt. Nanbu’s Hayabusa skimmed over the airfield. He dipped the wings, wrenched the plane high into the sky, and let the streamer go. It fell in on itself, coiling and uncoiling, a red thread against the fierce orange of dawn.

Lt. Kawasaki came from a small town not far from Chiran, Hayato, where many residents were old enough to remember when the first power lines went up. Twenty-eight, he had lived in Tokyo, where he became engaged to a girl who now refused to let him go.

Three days after he arrived, a young woman, pale, her monpé torn and filthy, dropped her pack inside the doors of Tomé’s restaurant. Did Tomé know a Lt. Kawasaki? Tomé brought her a cup of tea. “He’ll be here tonight,” she said, “but let’s get you into a bath, first.” The girl smiled, eyes glistening with tears.

Her name was Ayako. Tomé drew her bath and laid out a fresh cotton yukata. The guest rooms upstairs were empty, and Ayako was welcome to stay. Later, while Tomé was combing Ayako’s hair, still warm from the bath, Ayako said she was determined to marry Lt. Kawasaki. Tomé’s hand paused. “If we were married,” Ayako said, “I could meet him as his wife, when death came for me.” But Lt. Kawasaki’s parents were against it. “If they won’t let us marry,” she sobbed, “I’d rather die now, and wait the few days until he comes.” Her shoulders quaked under Tomé’s hands.

Lt. Kawasaki’s parents were already in Chiran to say good-bye. They knew about Tomé from their son’s letters, so when Tomé asked them to tea in an upstairs room, they accepted. She didn’t say anything about Ayako. Lt. Kawasaki came in at five. Tomé told him. “Thank you, Obachan,” he said, and headed for Ayako’s room. He was back in ten minutes. “She won’t listen to reason,” he said. “My parents are going to have to agree.” But his parents were adamant. Tomé hinted he was welcome to stay the night, but he returned to his barracks. That night Tomé didn’t sleep: She couldn’t prevent Lt. Kawasaki’s death, but she’d fight to keep Ayako alive.

The next day Lt. Kawasaki went up to Ayako’s room before he spoke with his parents. Ayako was in tears. His parents wouldn’t listen. He asked Tomé for help. Together they spoke with Ayako. Yes, Ayako said she understood. Yes, if that’s what he really wanted. No, she swore she wouldn’t.

Lt. Kawasaki piloted one of the thirty planes that left the next morning. Ayako had agreed with Tomé: She didn’t go to the airfield. When Tomé and her girls came home, Ayako was waiting, pack in hand. Tomé took her to the station, wiped away her tears, and told her to write. Ayako swallowed, managed a smile, and said she would.

A glass slipped from Tomé’s hand when Lt. Kawasaki staggered into the restaurant the following evening. Engine trouble had forced him to turn around. It was a familiar story: The army kept the best fighters for home defense and made the boys fly patched-up crates that often broke down. Still, to have sworn to die and come back alive was a sin. He went up a second time. And came back. “The pilots say it’s Ayako,” he said. “Her love is keeping me alive.” The boys shunned him. When he got his third plane he was elated. “She’s a beauty,” he told Tomé. “But I’m going to take her up tomorrow, just to make sure.”

Hayato was sixty kilometers away from Chiran. Lt. Kawasaki banked the plane and let the wind carry him. A flock of white herons winged over the river below, trailing their slender shadows over the silver water. Within minutes his home came into sight, its slate roof sewn into a patchwork of bright green rice fields. He came in low, hoping the engine’s whine would bring his family out.

Power lines are deceptive: when near, they appear distant. Two women, bent over a row of seedlings, looked up to see Lt. Kawasaki’s plane, landing gear dangling from the lines, shriek toward them. They turned to run. But it was too late. The plane tore into the field and killed them both. Lt. Kawasaki’s parents spilled from the house. But it was too late.

In the Battle of Okinawa, the Allied fleet numbered 1,457 ships and 500,000 personnel. The Special Attack Corps sank thirty-four ships and damaged 368, killing five thousand men.On April 1, 1945, the Americans staked out a beachhead on the island. Eighty-two days later, 110,000 Japanese soldiers and 75,000 civilians were dead. The Americans lost another eight thousand in the land battle. On August 6, a bomb exploded 576 meters over Hiroshima and the city vanished. Three days later, another bomb melted Nagasaki. The war was over.

The Americans were to come in the middle of December. Chiran’s chief of police scratched his head and asked Tomé to reconsider. Torihama-san, the town needs you. Sure, plenty of bars and cathouses have sprung up, but we need someone to make the Americans feel at home. “You’re asking me,” Tomé fumed, “to welcome the same men my boys died trying to protect us from?” The town needs you, Torihama-san. Tomé folded her arms. Well, the mayor planned to hold a welcome ceremony at Tomé’s; if she wanted to turn him down, the chief guessed she could.

A week later twenty-two marines shouldered their way into her restaurant. After the American captain topped off the mayor’s speech with a few words—Naka-san, a native of Chiran who’d lived in America before the war, doing the interpreting—bottle caps flew and the marines sprawled onto the tatami, bawling for food. As soon as Tomé slid the trays of satsumaáge, chikuwa, and fish and vegetable tempura onto the tables, the Americans started to holler. Naka-san fielded the questions: Of course, it’s edible, Tomé answered, it’s called chikuwa—chi-ku-wa; you hold the chopsticks this way; no, I don’t have any forks, and no napkins either. Amid the smoke, shouting, and thumps of empty bottles hitting the tables, a strange chanting filled the air. Naka-san shouted into Tomé’s ear: “‘More beer.’”

A week later, the marines burst through her doors again. “It’s a festival they call ‘Christmas,’” Naka-san explained. Japanese festivals were nothing like this, Tomé marveled. The Americans wrapped their arms around one another and, faces beaming, sang the cheeriest songs Tomé had ever heard. But then the songs—‘carols,’ Naka-san called them—sank into heavy dirges. Many marines, wiping tears from their cheeks, had to stop singing.

Naka-san came only on official occasions, but that didn’t stop the Americans from coming in to eat and drink and show Tomé photographs. “Take a look at these, Mrs. Torihama,” a boy with yellow hair called to her. A man about Tomé’s age, smiling next to a Ford. “This is my father,” the boy said. “And look, here.” A woman, gray-haired, in front of a picket fence. She was smiling, too, but in the way the woman clasped her hands Tomé saw an anxiety she knew too well. “And this,” the boy said. A girl, she reminded Tomé of Ayako. “We’re going to get married when I get home,” the boy grinned. “Mrs. Torihama, take a look at these,” another boy shouted. “Mine, too!” They all had pictures. “Hai, hai,” she said, and before she knew it, she was smiling. She couldn’t understand a word, but she knew what the boys wanted to say—she heard it under their voices, saw it behind their eyes.

A week later Tomé was slicing potatoes when Reiko marched into the kitchen. “Mother,” she said, “you’ve got to stop coddling these Americans. People in town are starting to talk.” Tomé put her knife down. “Reiko,” she said, “would you have me turn them away? Here they are, on the other side of the world, surrounded by people who hate them. Can you imagine how they feel?” Reiko knew what Tomé was talking about, but still…. “If you can’t,” Tomé said, turning back to her cutting board, “you can at least be patient; they’ll be gone soon.”

Tomé knew where the boys went most nights, and what they did. She couldn’t understand why they came to her restaurant, though. “Mama, another round here!” a marine called out. When had they started calling her Mama? Another boy waved a sheaf of paper at her. “Mama, let me read this letter to you.” She sat down and listened, smiling at the places where the marine’s eyes brightened. “No, they don’t,” Naka-san told her one night, after she’d mentioned the boys called her Mama, just like they did the bar girls and brothel madams. “They call them Mama-san,” Naka-san said. “The only one they call Mama is you.”

The Americans left at the end of February. “Mama, sayonara!” they called, waving from their jeeps. Reiko was astonished to see that many of the men were crying. Her mother and Miako were wiping tears from their eyes, too. Reiko had liked playing cards with the marines, and had enjoyed the festivals—“birthday parties,” they called them. Reiko ran into the street. “Sayonara, sayonara,” she shouted, as the line of jeeps, blurred through her tears, disappeared around the corner.

It happened early in the morning, a week later. The restaurant was empty. Tomé had just finished setting out the last ashtray. She sat down and slung her towel over her shoulder. Voices. Her boys’ voices. She looked up. Lt. Nakashima, sitting at a far table, raised his glass and smiled. “It’s good to see you again, Obachan,” he said. Lt. Abé and Lt. Kawano stepped in from the shadows. “Obachan,” Lt. Kawano said, “can you make this? Our mothers used to make it for us,” Yes, yes, of course, Tomé said, standing up. She pulled her towel down and headed for the kitchen. “Mama,” another voice. “Mama, how do you eat this?” She turned. It was the boy with the yellow hair. “Mama, this is Betty. Isn’t she a doll?” The boys’ voices faded. “Obachan, arigato. Wasuremasen yo.” Tomé closed her eyes, afraid that when she opened them her boys—all her boys—would be gone. “Thanks a lot, Mama. I’ll never forget you.” She opened her eyes. They were gone.

Tomé, bucking the wave of anti-militarism that swept the nation after the war, fought to have the government recognize the Special Attack Corps’ sacrifice. In 1955, Tomé attended the unveiling of the memorial to the pilots, a statue of Kannon, the goddess of mercy. The memorial was erected with government funds. Tomé prayed at the memorial every day for the rest of her life.

Reiko went to study in Tokyo that same year. Tomé was blessed with another grandson in 1960. In 1965, Tomé’s husband died. Nine years later, cancer took Miako. The people of Chiran built a museum to house the items the pilots had left behind. The museum was expanded and reopened in 1987.

On May 3, 1945, the last night of Lt. Katsumata’s life, he asked Tomé to come outside. The air was cool, and the stars glowed brightly. “I’m going to die, tomorrow, Obachan,” he said. Tomé drew in her breath. “You know the proverb, ‘live to be fifty and die content’?” he asked. “Obachan, you take my thirty years. Be happy.” Tomé passed away in 1992. She had lived Lt. Katsumata’s thirty years, and seventeen more.

In 1995, a television producer from Seoul called Reiko. He was making a documentary and wondered if Reiko could verify a rumor he’d heard about a Korean volunteer for the Special Attack Corps. Reiko’s grip tightened on the phone. She told him about the evening of May 10, 1945. Yes, she’d be glad to sit for an interview. Four days later ten men, shouldering cameras and microphones filed through her door. Reiko recounted her story, mentioned the song they sang, and—. Excuse me, the interviewer said, a song?

Yes, Reiko said, and began to sing:

Arirang, Arirang, Arariyo

Now that you have left me

And gone over the pass of Arirang….

The interviewer began to sing. So did the other men. Tears streamed down their cheeks. Lt. Mitsuyama was on his way home.

The documentary aired on Korean television. Three of Lt. Mitsuyama’s cousins were among its viewers. The eldest cousin flew to Tokyo to talk with Reiko. She told him everything she remembered: the walks along the river; Lt. Mitsuyama’s favorite spot under the trees. He enjoyed the sound of the riffles in the brook, she recalled, smiling. During the conversation, Reiko learned Lt. Mitsuyama’s story: His mother, determined to have her son accepted in Japanese society, fought to get him an education. He became a pharmacist, filling her with a pride rivaled only later, when she saw him resplendent in an Imperial Army Air Corps dress uniform. After she died, suddenly in December, 1944, Lt. Mitsuyama volunteered for the Special Attack Corps. He put his father and sister—she’d been born in Japan—on a steamer bound for Pusan. He left no address for Tomé to find. Lt. Mitsuyama’s father and sister have since passed away, the cousin told Reiko. They never knew how Lt. Mitsuyama died.

Since 1996, one of Lt. Mitsuyama’s cousins has joined Reiko at the memorial service held in Chiran every May 3. They pray, hold hands, and gaze into the southern sky. In Chiran, the cherry blossoms come out in late March. The winds, though, quickly sweep the fragile flowers from the branches and, by May, the petals have disappeared.

This article was adapted from the book, Hotaru Kaeru (The Firefly Returns), written by Mr. Ishii Hiroshi, based on the recorded oral recollections of Tomé’s daughter, Mrs. Akabane Reiko, and Mrs. Akabane’s extensive collection of letters, diaries, and other documents of the period. Hotaru Kaeru is printed by the Soshisha publishing company. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Mr. Ishii and Mrs. Akabane for granting me permission to publish this article. I am particularly indebted to Mr. Ishii, whose patient guidance was indispensable in preparing this article for publication.

Tomé’s restaurant, Tomiya, is now a museum.