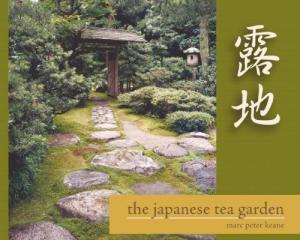

The Japanese Tea Garden by Marc Peter Keane. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 284pp.

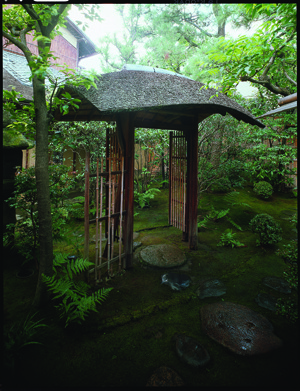

[A]s the Meiji era art critic Okakura Kakuzo says in his classic Book of Tea, “Teaism is a cult founded on the adoration of the beautiful among the sordid facts of everyday existence.” On a similar note of willing disassociation, Japanese garden authority Marc P. Keane writes, “To walk the length of a roji (tea garden) is the spiritual complement of a journey from town to the deep recesses of a mountain where stands a hermit’s hut.” In both instances, the journey down the green, powdery corridor of the tea garden is understood to be transformative.

The Chinese, who first provisioned the Japanese with the plant, characterized green tea as liquid jade. My own initiation into a greater appreciation of tea came not in my native England, where packets of anemic Brooke Bond tea bags did service for most people, but many years later in China’s Yunnan Province. There, in the courtyard teahouses of Lijiang and Dali, tea drinking became a rarified pleasure as one sampled Tibetan, eucalyptus, hay, liquorice, chrysanthemum, and the acerbic, woody taste of Snow Tea. Elevating plain sampling to ritual pleasure, was an elaborate Three Courses tea set, consisting of bitter tea made with Mao Jin Spring Tea, a second course with thin slices of local cheese and black tea with honey and walnuts, followed by a “return tea taste” course, consisting of dry, fragrant tea mixed with prickly ash.

Keane, who is extraordinarily well-grounded in the history, institutions, arts and aesthetic priorities of China, explores the customs and state of mind requisite for the higher appreciation of tea in the Middle Kingdom and acknowledges Japan’s historic debt, but is at pains to point out that the Japanese achievement was not simply to refine the consumption of tea, but to create a distinctive tea environment. The tea garden and teahouse were places where a specific and particular social ecology existed, where etiquette, aesthetics, and a multitude of other graces deemed necessary for a person to be truly urbane, could be acquired.

Keane’s book, like the process by which a novice enters the tea world, is an initiation into finer things. The writer possesses the uncommon ability to situate the reader in the roji, to recreate the spirit and texture of either a contemporary or a four-hundred-year old garden, and does so with the skill of a master cultural navigator.

Arguably, of all types of Japanese garden, it is the roji that is the least understood. Compared to the grand gardens of the Edo period, the tea garden is small, but at the same time subtly enlarged through an entire cosmology of elements, symbolism and themes. It is this enhanced world that Keane explores. The author reminds us that to understand one art you must be learned in others. It may, for example, be initially difficult to grasp the idea that, “the fundamental pillar of tea was, and is, Zen Buddhism,” but this fact illustrates the inter-connectedness of Japanese practices and art forms. With its philosophical and Buddhist accretions, the veneration of tea can become almost a cultural séance, an esoteric practice baffling to the layman.

Arguably, of all types of Japanese garden, it is the roji that is the least understood. Compared to the grand gardens of the Edo period, the tea garden is small, but at the same time subtly enlarged through an entire cosmology of elements, symbolism and themes. It is this enhanced world that Keane explores. The author reminds us that to understand one art you must be learned in others. It may, for example, be initially difficult to grasp the idea that, “the fundamental pillar of tea was, and is, Zen Buddhism,” but this fact illustrates the inter-connectedness of Japanese practices and art forms. With its philosophical and Buddhist accretions, the veneration of tea can become almost a cultural séance, an esoteric practice baffling to the layman.

Keane helps by explaining the social, religious and martial background, realms the relevance of which may not always be apparent to the casual tea garden visitor. Placing the practice of tea into the complex perspective of class, wealth and accomplishment, he notes a degree of contrived humility in creating a modest tea garden—an extremely costly undertaking. The soan chashitsu, the rustic-style teahouse is a purely aesthetic contrivance: constructing one is beyond the means of all but the wealthiest. The tea world is full of such exquisite oxymorons.

Keane traces the development of ostentatious tea ceremony events from more chaste and muted affairs that allowed for a permissibly brief social leveling. Looking at tea and gardens from original perspectives, he ponders the tea aesthetics of three very different masters: Rikyu, Oribe and Enshu. He examines their respective tastes and ideas by analyzing the type of ceramic bowls they favored.

Rather than fixate on the tea master Sen Rikyu, as many writers have done, the author profiles the lives of several figures pivotal in the formulation of tea and garden styles, such as Takeno Joo, Imai Sokyu and Tanaka Soeki. It is interesting to learn that many of these masters, far from being the forest hermits and recluses we might like them to have been, were often men of the world. Sen Rikyu himself was a trader, successful in, among other things, the arms procurement business.

The extremely detailed text will require your full attention. The author’s collective entries on the function and place of the chozubachi (water laver), for example, are longer than the entire texts of some tea garden books. We learn of physical forms that are more symbolic than utilitarian, such as the chiri-ana, a hole for placing garbage. More likely to contain a picturesque assemblage of leaves, broken twigs and bamboo than actual trash, it has traditionally stood for the “dust of the heart,” that should be left behind before entering the tea room.

Keane steers us through the difficult nomenclature of tea aesthetics, the fine-tuning of taste, connoisseurship, and the appreciation of beauty. Along the way, there is discovery and gratifying recognition. No one has ever been able to tell me the name in Japanese of the circular pedestal stones supporting wooden columns in Buddhist temples that are used to lend an air of antiquity and spirituality to certain gardens. Now I know they go by the name garan-seki, and that the correct term for stepping-stones with a disk shape carved into their tops, is niwa-garan. And the hitherto un-translated nezumi-mochi in my own garden, I now know to be called a “Japanese privet.” Thus, the book succeeds as lexicon and treatise, glossary and tractate.

Impeccably written, erudite without being burdensomely intellectual, what sets Keane’s beautifully measured and considered prose style apart from other garden writers is the carefully created mood of his text, which aspires at times to verbalized contemplation. It is the first book of this depth and scope to appear in English, and is likely to remain the standard work on the subject for a very long time to come.