[I]t is dusk when Khampone and I arrive at the edge of his village, in the Xekong river valley in the remote southeast corner of Laos, about fifty miles from the border with Vietnam. As the sun drops below the horizon behind us, some of the heat lifts, but it is still in the high nineties, and there is no breeze in this valley in April, nearing the height of the dry season. Around us the trees of the dry tropical forest have dropped most of their leaves, revealing in the distance the foothills of the Annamite mountains, the beginning of the frontier, where the upland forest tends into evergreen.

[I]t is dusk when Khampone and I arrive at the edge of his village, in the Xekong river valley in the remote southeast corner of Laos, about fifty miles from the border with Vietnam. As the sun drops below the horizon behind us, some of the heat lifts, but it is still in the high nineties, and there is no breeze in this valley in April, nearing the height of the dry season. Around us the trees of the dry tropical forest have dropped most of their leaves, revealing in the distance the foothills of the Annamite mountains, the beginning of the frontier, where the upland forest tends into evergreen.

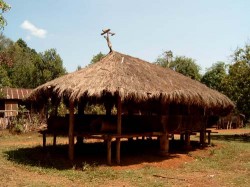

Khampone’s village is a collection of a dozen thatch-roofed houses on six-foot stilts, arranged in a circle around a central communal structure, in the style typical of the ethnic minorities indigenous to this part of Southeast Asia. Each house is home to a family of five to ten people, making this village small, even by the standards of the indigenous groups in this thinly-populated part of Laos.

Tonight, however, there are several more inhabitants making their presence loudly known: a crew of Vietnamese loggers camped out by the near-dry creek that runs behind Khampone’s house. They are done with their tree-felling work for the day, now concentrating on an aggressive game of cards spiked with rough rice whiskey. A boom box hooked up to a corroded motorbike battery blares out the plaintive pop of a well-known Vietnamese diva.

Tonight, however, there are several more inhabitants making their presence loudly known: a crew of Vietnamese loggers camped out by the near-dry creek that runs behind Khampone’s house. They are done with their tree-felling work for the day, now concentrating on an aggressive game of cards spiked with rough rice whiskey. A boom box hooked up to a corroded motorbike battery blares out the plaintive pop of a well-known Vietnamese diva.

“The logging started a few years ago, first at the south edge of the village, now around the middle and towards the mountains,” says Khampone, who like most indigenous people in Laos uses only one name. “We don’t agree with the decision to log, but their bosses come with government officials from the province, with papers signed by the Governor himself. They have made it legal, so what can we do?”

In the last few years, an increasing amount of timber has been mined out of the frontier forests of Laos, nearly all of it bound for Vietnam, the “big brother” of its smaller, less developed, landlocked neighbor to the west. Here in Xekong province, as in most other areas in Laos, almost all the remaining forest with stands of commercial timber fall within the customary boundaries of indigenous groups like Khampone’s, subsistence farmers whose lives have traditionally existed on the margins of society, largely outside the cash economy.

But as more accessible forests in Laos are logged out, and as Vietnam’s economy — and particularly its wood industry — develops at a breakneck pace, communal forests on the frontier like those of Khampone’s village are increasingly being targeted by the Lao political elite and their Vietnamese private sector partners to supply the raw material for the lucrative timber trade. In the process, and despite national laws to the contrary underwritten by Western donors, villagers are paid a pittance, if anything at all, for the precious hardwoods removed from their lands, timber that fetches high prices on the international market. Much of the wood ends up as furniture in North America and Europe.

It is a reality that stands in stark contrast to the image of Laos touted by the tour books: the “Shangri-La” of Southeast Asia, the new hip destination for a growing number of eco-chic travelers drawn to Laos as an unspoiled natural wonder, where the “real Asia” can be experienced. Beyond the high-end ecotourism retreats, in frontier country, logging and the timber trade are stripping countless villages of their most valuable resource — the timber removed from Khampone’s village last year alone was worth upwards of half a million dollars — while enriching a small clique of the Lao political elite and Vietnamese sawmillers, all in the name of economic development. “Laos is a paradise, like I told you in Paris… Only, like paradise, Laos doesn’t exist; it’s a figment of the imagination of a few French administrators.” So writes Jean Larteguy in his 1967 novel The Bronze Drums, which chronicles the political machinations of a French intelligence officer posted to Laos after World War II. This kind of characterization of Laos, as an imaginary country, is rife in popular writing about the country. It is often described as a non-state, an artificial construct, an accident of history, in part because the ethnic Lao themselves constitute only just over half the total population of about six million people. The other half is a collection of a huge diversity of ethnic groups (the government counts sixty-eight groups officially, but an anthropologist recently found 236 distinct language groups) whose customs, languages and livelihoods share few similarities with that of the Lao.

The borders of modern Laos were first staked out under a treaty agreed between the French and Siamese in 1893, as France sought to expand the boundaries of l’Indochine to include both banks of the Mekong River. During its fifty-year colonial rule, France mostly ignored the “land of the lotus eaters,” a term of paternalistic endearment for les Laos, who were considered care-free, malleable and lazy. Laos itself was never considered worthy of nationhood in its own right; on the contrary, many colonialists argued that France should facilitate a Vietnamese takeover of the hinterland to its west, which in any case was seen as inevitable.

“We cannot attempt any enterprise in this country, so rich but so unproductive due to the fault of its possessors,” wrote Jules Harmand, who headed one of the early French expeditions to southern Laos. “It is necessary first that the Laotians be eliminated, not by violent means, but by the natural effect of competition and the supremacy of the most fit.” By the most fit he meant the Vietnamese, who were brought in to labor on the few development projects undertaken in Laos, to populate the towns, and, most important for the colonial regime, to pay taxes. By the 1940s, the country’s capital, Vientiane, was over half Vietnamese; in the Mekong town of Thakek, one of the largest in Laos, the figure was eighty-five per cent.

Unfortunately for the French, this mixing with the Vietnamese carried over into the political realm, with a faction of the nascent Lao independence movement ultimately joining the Indochinese Communist Party, founded in Hong Kong in 1930 by an exiled Ho Chi Minh. At the end of World War II, confusion over France’s colonial holdings reigned; Ho stepped into the power vacuum, declaring Vietnam independent and inspiring a group of Lao communists – the Pathet Lao – to resist a return to French rule. For the next nine years, France struggled to regain its foothold in Indochina, ending famously with its defeat at the hands of Vo Nguyen Giap’s army at Dien Bien Phu. The resulting peace accords, signed in 1954 in Geneva, split Vietnam at the seventeenth parallel into north and south, and declared Laos, along with Cambodia, to be a neutral and independent country in the emerging Cold War cauldron.

The secret sideshow to the Vietnam War that followed in Laos in the sixties and early seventies pitted the CIA-backed Hmong against communist North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao troops in seasonal battles on the Plain of Jars. At the same time, the US military ran near-constant bombing missions up and down the Ho Chi Minh trail, the ever-mutating network of forest tracks that were mostly inside Lao territory. The war left Laos the most bombed country per capita in history, suffering the equivalent of all the bombs dropped on Europe during World War II combined, or one bombing mission every eight minutes, every day for nine straight years.

Despite these jarring statistics (not to mention the grim continuing reality of unexploded ordnance that maims thousands every year to this day in Laos), the war was never much a part of reality for most of the populace living in the big Mekong towns, far from the fighting. Nor was there much revolutionary fervor among most of the Lao. A small band formed a hard core of the communist Pathet Lao in the “liberated zone” in the northeast, but all the arms, training and ideology (and indeed the bulk of the troops) came from Hanoi. The man who emerged as the leader of the Lao revolution, Kaisone Phomvihane, was himself half Vietnamese, trained in Hanoi, and married to a Vietnamese woman. From the very start, the “rebellion in Laos,” as the propaganda brochures written and printed in Hanoi called it, was closely managed by the North Vietnamese.

When the war was over and the Lao People’s Democratic Republic was declared in early 1976, few of the dramatic scenes that accompanied the fall of Saigon took place in Laos, and nothing even close to the “Year Zero” mania that gripped Cambodia under Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. Thousands of Hmong fled Laos, and many with connections to the deposed Lao royal family were jailed, but the revolution was, by comparison, a decidedly un-revolutionary affair. There was little industry to speak of to be nationalized, and agrarian collectivization was abandoned after a few years of failed experimentation. The new Lao government – under the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party – displayed little of the bombast and confrontational theatrics that the Vietnamese seemed to relish, even allowing the US Embassy in Vientiane to stay open, the ambassador post merely downgraded to a chargé d’affaires.

This lack of zeal for hard line Marxist reforms revealed the extent to which the Lao were accidental communists, and reflects the deep ambiguity felt among most Lao people about the philosophical roots of their government, an ambiguity that has only grown over time. In stark contrast to Vietnam, where streets are named after revolutionary heroes, and nearly everyone can quote (or spin elaborate jokes) from the sayings of Ho Chi Minh, most Lao people display a startling lack of interest in their so-called revolutionary history. The Communist Party has responded to this by deploying some of the tried-and-true methods of communist propaganda: socialist-realist artwork on billboards, exclamatory revolutionary slogans on bright red banners, even an attempt, in the wake of the Soviet collapse, to create a cult of personality around Kaisone Phomvihane.

But it has all failed rather obviously. The revolutionary posters are peeling, the banners hang lopsided, and the sprawling Kaisone museum at the edge of Vientiane, fronted by a surreally large golden statue of Kaisone (a gift from North Korea), is almost always deserted. (In Hanoi, by contrast, still to this day, droves of the faithful stream in from the countryside on weekends to get a glimpse of Uncle Ho in his mausoleum.) Ask the average Lao person to tell you a vignette about Kaisone or to recount a tale of the revolution, and you are likely to get little more than a laugh and a shake of the head. Most Lao people simply don’t care much about the revolution, and bear all the propaganda with their trademark light-hearted fatalism.

[D]espite these failed attempts to engineer the kind of revolutionary zeal found in neighboring Vietnam, the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party maintains a remarkably firm grip on political discourse and decision-making in the country. While Vietnam has slowly allowed for limited decentralization and greater press freedoms since introducing economic reforms in the 1980s, the Lao regime has resisted any political opening.

“Since the formation of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic in 1975, all political power has been monopolized by the Party,” says Martin Stuart-Fox, a professor of history at the University of Queensland, Australia, who covered Laos for United Press International during the war and is one of the few academic authorities on the country. “Political dissent of even the most limited kind, in the form of political study groups or small peaceful demonstrations, is quickly suppressed, using the full coercive power of the state. Simply put, anyone with political ambitions has no alternative but to join the Party.”

Whereas in Vietnam and China party bureaucracies are struggling to stay relevant and keep members, in Laos the Party is as strong as ever. Membership is by invitation only, and even government officials can expect to wait ten or fifteen years, going through elaborate pre-membership rituals and evaluations to prove their commitment to the Party, before being accepted at a junior level. (The process is of course much speedier, or simply skipped altogether, for those with family connections to top-level cadre.) In short, it is the kind of highly centralized system that once dominated many communist countries during the Cold War years, but which has largely disappeared elsewhere, with the exception of North Korea.

Behind, throughout and on top of the Party is the Army. Of the eleven-member Politburo, the most powerful decision-making body in the nation, the majority are military men, giving the Lao leadership the distinct feel of a military junta, not unlike Burma, though much less widely reviled.

“In Laos there are two political realities,” according to a US State Department official, who like most other foreign nationals interviewed for this article requested anonymity to safeguard access to the country. “On the face of things there is the civilian government, which is ultimately a rubber-stamp body. It is mostly a showpiece for outsiders. Then there is the Party, which is controlled by the military. They make all the decisions. They are the real government.”

Ties to Vietnam, which kept over thirty thousand troops in Laos until a few years ago, are still extremely strong. Virtually the only way up in Lao political life is through Vietnam; without spending a year or two at the Ho Chi Minh National Political Academy in Hanoi, or one of a handful of other Party schools in Vietnam, it is nearly impossible to be promoted. “It is hard to overemphasize how much Vietnam still controls decision-making in Laos,” says the State Department official. “It is still in many ways a vassal state relationship. Even with seemingly insignificant decisions, like approving small development projects, the leadership in Laos still turns to Vietnam for advice.”

Continuity in the apprentice relationship established back during the war years is still of great strategic importance to the Vietnamese, though now the impetus has changed. If during the war Laos was strategically important as a route to send arms and men to South Vietnam to aid in the insurgency, now Laos is important as a source for the raw materials needed to fuel Vietnam’s economic growth, which has consistently ranked second in the region in recent years, just behind China.

Laos is the perfect source: next door, politically docile, thinly populated, and rich in rivers, minerals and timber. And it is in places like Xekong province, on the lands of indigenous villages, where the frontier is being exploited most severely.

[ T]he main road to Xekong, paved only a few years ago, comes up from the big Mekong river town of Pakse, winding up over the Bolaven plateau and then down into the valley of one of Southeast Asia’s great rivers, the Xekong. These days the drive takes only two hours or so, but in traveling its arc over such wildly divergent landscapes, it seems to take much longer. Leaving the lowland Mekong plain, with its distinctive fluorescent green rice paddies dotted with ragged palms, the road climbs steadily up to the hill town of Paksong, the vegetation getting darker and wetter with each passing village, their sloping roadside home gardens crowded with coffee trees.

At the top, 4,500 feet above sea level, pines appear, and it is almost always shrouded in a misty grey rain. Heading across the plateau, the landscape turns to a savanna-like woodland, with tall grasses and scattered low shrubs. Patches of forest hang over the plains on the wetter hilltops, a few old-growth emergents stamped against the sky. Crossing into Xekong province, the long, slow descent into the river valley begins, and the vegetation changes again, back to lowland forms. Created only in 1984, Xekong province is still a wild, strange and very different place. The World Wildlife Fund identifies it as one of the most important places on earth for biodiversity, with some of the largest tracts of intact primary forest remaining in mainland Southeast Asia. These forests are home to several critically endangered large mammal species, including tigers and Asian elephants, plus two deer-like animals only recently described by science.

Matching the province’s biological diversity is its richness in human cultures. A patchwork of fourteen distinct indigenous groups, who collectively account for over ninety-five percent of the province’s population, live spread out over the mountains of Xekong. They employ a wide set of subsistence-oriented strategies for survival, and rely heavily on the forest for practically every aspect of their livelihood — food, water, shelter, fuel, crafts, and religious practice.

“Xekong is still a very peripheral place,” says a Canadian development worker who works with indigenous groups here. “It still has all the elements you read about Laos having – the big forests with endangered wildlife, the isolated cultures with strong traditions – but that are in fact increasingly hard to find in this country, or anywhere else for that matter.”

But Xekong is almost done being so peripheral. Upon crossing the provincial border, the road gets bumpy and slow, pocked with potholes the size of hubcaps, which are the marks of fleets of old Russian-made log trucks that rumble through here during the logging season. Nearly all their cargo — huge tropical hardwoods, some up to one meter in diameter, that can fetch upwards of $7,000 per stem — comes from indigenous villages out on the periphery.

Year by year, the logging frontier moves on, leaving in its wake villages that have had their most valuable resource removed, often with no compensation. If they are lucky enough to be given some cash, it usually amounts to around one dollar per cubic meter, or less than one percent of the market value of even the low-grade species in their forests.

“Most of the time, the logging companies and the government don’t pay us at all,” one village chief downriver from Khampone’s village tells me. “If they do, what they give us is enough to eat in the hard months. But what they take away makes the hard months last even longer. And soon there will be no trees left.”

The systematic removal of timber from their lands is in direct violation of Lao forest legislation, pushed through by the World Bank and other donors. The laws, written initially in English by foreign consultants and passed by the government in 2003, require that timber harvesting only commence in areas designated as “production forest” with an approved management plan, developed together with local villagers. The legislation also requires that villagers be involved with all aspects of forest planning and management, and that they be paid the equivalent of 17.5% of the roundwood market value of the timber harvested.

“A great deal of energy and time and money has been spent on improving forestry in Laos over the past ten or fifteen years,” says a European development consultant who has been working on forestry issues in Laos for over a decade. “Unfortunately, there is not really much support from the government to implement the policies that have been passed. Nor is there much interest in confronting the issue honestly and discussing it with outsiders. It is hard to admit, but I haven’t seen much real progress on the ground, despite all the investment. If anything, in recent years, it has gotten worse.”

On paper, the government has been restricting timber harvesting each year since 2001. But in reality, all indications suggest that logging is on the rise. A recent report by the US government estimated that over 600,000 cubic meters of timber was being illegally harvested and sold out of Laos every year, with a market value of at least $300 million. But other estimates vary widely, and in fact there are no reliable statistics.

“It is almost impossible to know just how much is being logged,” according to an American forester working for an environmental conservation group here. “There are too many layers of interests, and there are so many ways that they cover up what they are doing. The government itself recently admitted to more than fifty thousand cubic meters of illegal harvesting per year. But of course what they admit to has to be far below the real figure. I usually triple whatever it is I’m told is being removed, and this is only tallying what the civilian agencies are logging. Then there is the whole world of the Army, who control all the border forests, and who do everything hand-in-hand with the Vietnamese. No one can get access to information about what they are doing. The fact is that no one really knows just how much is being logged out of Laos.”

What is clear, however, is that many of the Lao political elite, along with their private sector partners from Vietnam, are getting very rich off the timber trade. At its root, this is the reason why, despite considerable pressure from Western donors, forest laws are not enforced. In places like Xekong, there is little else to make money from, and the forest seems inexhaustible. It is, as the American forester put it, “a curse of abundance.”

[O]ne of the most powerful individuals in the Xekong government is Bounthone Panyalith, special assistant to the Governor and chief for the province’s foreign affairs. His office is on the third floor of the main provincial administrative compound, a hulking mass that is a strange meeting of blocky socialist-realist architecture and the swooping eaves of a Buddhist temple, situated just off the main public square of Xekong’s capital, called Lamam.

[O]ne of the most powerful individuals in the Xekong government is Bounthone Panyalith, special assistant to the Governor and chief for the province’s foreign affairs. His office is on the third floor of the main provincial administrative compound, a hulking mass that is a strange meeting of blocky socialist-realist architecture and the swooping eaves of a Buddhist temple, situated just off the main public square of Xekong’s capital, called Lamam.

Lamam is a recent invention. Aerial photographs taken by Soviet reconnaissance in the early 1980s show nothing but a bend in the river and the crowns of riparian forest trees in the place where the town now stands. Like the ultra-modernist capitals of Brasilia or Naypyidaw, Burma’s new seat of government, the dream with Lamam, when it was established in 1984, was to domesticate the frontier by carving a city out of the wilderness that the province’s overwhelmingly indigenous population would migrate to, sparking economic development and ultimately assimilation to ethnic Lao ways.

Today, the town is a simple grid of half-paved roads straddling the main north-south highway in southern Laos, sprawling out over an area that seems excessive for its population of about five thousand people. At the west end of town is a large open public space, Xekong’s Red Square, which is mostly weeds and low grasses, except in the places where regular foot or bicycle traffic has worn through to form trails. The square is bordered on one side by an overgrown and largely ignored shrine to Kaisone, some half-hearted graffiti sprayed over a revolutionary slogan engraved beneath his copper-hued bust. On the other side, a lone wolf tree, randomly left standing during forest clearance, mercifully shades an arc just off the official viewing bleachers, a whitewash structure presumably built for the kind of military parades common in Laos in the 1970s and 80s, but which never took place here.

Emblazoned across the top of the bleachers is a kind of triptych articulating the vision for Xekong. The left panel shows a river with thick forest along its banks, high mountains hanging in the distance, and birds circling above. On the right is a modified picture of the same scene, but now with the right-angle patchwork of rice paddies, a wide blacktop road, and a Buddhist temple. In the middle, the enabling bridge, is the coat of arms of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

Bounthone’s job, as he puts it, is to attract as much foreign investment as possible to Xekong, in order to develop the province’s infrastructure and services, and to pull the indigenous groups out of poverty. Most of his partners in this work are from Vietnam.

“The toughest job here in Xekong is getting the investment,” he tells me, the blast of air conditioning in his office mixing with cigarette smoke and hot air coming in through a propped-open window. “In general, Laos is poor. But even among other Lao provinces, Xekong is the poorest. So the question is, how do we attract long-term investment to a place that has no roads and no labor force? That is why we have to start from the bottom up, with our province’s abundant natural resources. This is the way we can build up the economy.” On his desk, prominently displayed, are contracts with several of Vietnam’s biggest timber processing firms.

Bounthone is part of a small group of men that form the inner circle of Party members in Xekong. Headed by the Governor, this inner circle meets once a month, and in keeping with the Leninist principles of total Party loyalty — but also in a kind of incarnation of a traditional Lao village-level council of elders — they make consensus-based decisions on virtually every matter of any significance in Xekong, from political shuffles to approval of investment projects to managing rural development efforts. It is the height of micromanagement. For those outside this inner circle, it is almost impossible to exert any influence over their decisions, without considerable political clout and considerable cash. And in Xekong, the few who have either are Vietnamese in the timber business.

[L]e Trong Hung is one of the great success stories of Vietnam’s post-Cold War economic boom. Born into a poor household in Vietnam’s Central Highlands, his hometown was mostly on the side of the US during the Vietnam War, and his family was full of South Vietnamese soldiers, yet somehow he managed to avoid persecution after the fall of Saigon. Like so many others in his country of voracious entrepreneurs, he jumped at the chance to start up his own business when the Vietnamese government opened the economy in the late 1980s.

Skinny and hollow-cheeked, with a comb-over of black hair, Hung now has the markers of wealth so coveted by his countrymen – a successful garden furniture business with six sawmills feeding a processing plant, a fleet of shiny new cars, a pair of mansions (one outside of Ho Chi Minh City and one near his hometown), and two children studying in the US. “We dumped everything we had into building up our capacity in the early days, and we had to survive on almost nothing, faith alone,” he recounts for me, chain smoking through dinner at one of Xekong’s two restaurants. “But by 1999, we were exporting dozens of shipping containers per month to the US and the EU. Now our business only continues to grow.”

Hung isn’t alone. The Vietnamese wood processing sector has exploded in recent years. In 2006, wooden furniture exports alone reached nearly $2 billion, a ten-fold increase from the year 2000, with the vast bulk of it going to Europe and North America.

The problem, however, is that there is almost no domestic wood supply in Vietnam, which is thinly forested and overpopulated. For the past ten years the Vietnamese government, at the urging of Western donors and environmental groups, has severely curtailed timber harvesting in its natural forests, focusing instead on protection and plantation establishment.

“While Vietnam has made impressive progress in reducing natural forest loss within its national boundaries, the Vietnamese authorities have stimulated expansion of the country’s already significant timber processing industry,” says Mike Davis of Global Witness, a London-based environmental group. “The effect has been to export the environmental, social and economic problems caused by illegal logging and forest degradation to its neighbors, particularly Laos, which has weak natural resource governance and high levels of corruption. The Vietnamese government appears to be deliberately taking advantage of these conditions, which raises the question of whether Vietnam sees its relationship with its weaker, more resource-rich neighbor as being one based on genuine partnership, or exploitation.”

Though some Vietnamese companies with links to markets in the EU and North America have pledged to source their timber only from forests that have been certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, an international benchmark of sustainable management, in fact only a small proportion of the wood they use is from legally verifiable sources. Much of the undocumented and illegal material that fills the void is from Laos.

Last year, Hung’s operations in southern Laos, previously minimal, tripled to 20,000 cubic meters (nearly 8.5 million board feet), and he is now building a new sawmill in Xekong, off the road running up to the plateau.

Again, he is not alone. At least five sawmills are under construction in the province, all with Vietnamese investment. At one of Xekong’s two restaurants – which stand next door to each other and compete in a strange sibling rivalry, one being owned by a half-Vietnamese man, the other by his sister – the bulk of the clientele are Vietnamese in the timber business. Their SUVs – Land Cruisers, Lexuses, and Mercedes – compete for space under the few trees that give shade in front of the wood-and-thatch eateries.

More often than not, one of the Xekong clique of Party members is in attendance, being wined and dined on a Vietnamese tab. These dinners and other more expensive “gifts” to the inner circle are their ticket to receiving quotas for timber removal. Each year, the players are ranked according to the gifts they give – those with the higher quotas having given the more impressive gifts.

“In other countries, the political culture surrounding timber is often termed a ‘kleptocracy,’” explains a development worker here. “But to me, here in Xekong, it is more of a ‘tributocracy.’ The way that it is handled is very much in keeping with both the traditions of Lao politics and the long history of paying tribute to more powerful entities, be they internal or external.” This tributocracy of timber explains how, on an official salary of less than $100 per month, the top leadership in the province can afford to own a $50,000 car and several large houses. It also explains why there is so little incentive to implement the laws passed at the insistence of foreign donors.

[T]he opening party of one of the Governor’s new sprawling mansions, a “gift” from a local sawmiller, is one of the biggest gatherings Lamam town has ever seen. In a literal arrangement of the constellation of power, at the center of it all are several of Xekong’s inner circle – flanked by two of the province’s biggest sawmillers. A Lao woman in full traditional regalia serenades them, hitting perfectly the staccato off-rhythm notes of a Lao lam, an ancient singing form whose melodies are rooted in word tones. With each turn of stanza, she moves with unerring and postured grace to the next man in the circle, wishing long life and prosperity in recitation, offering up a tiny porcelain cup with a shot of Minh Mang wine, a Vietnamese specialty believed to be an aphrodisiac.

The Governor’s newly-unveiled gift, like the handful of others that have sprouted up in this town, is a rambling three-story colossus whose walls, flooring and moldings are of the two most precious Lao hardwood species – rosewood (Dalbergia cultrata) and padauk (Pterocarpus macrocarpus) – as is all the clunky furniture, so heavy it seems fixed to the floor. Inside, Khampeth Chanthavong, the most powerful figure in the forestry agency in Xekong, holds forth on the issue of logging with a bottle of Johnnie Walker and Thai-brand soda water.

“One thing that has to be understood is that this province needs to develop, and we cannot get enough money from the central government to help our people,” he says, clad in a button-down Batik silk shirt in the style made famous by several of Southeast Asia’s most notable dictators. “That is why we are seeking investment from the outside. The money we make from logging will be used to develop the countryside, to lift our people out of poverty, and bring them out of the forests. The foreigners who are trying to run projects here, they are not interested truly in poverty alleviation, in developing Xekong. Their only interest is to keep the forest, to save the monkeys, but for who? If their plans are followed, the people will stay poor and Xekong will never change.”

[K]hampeth’s words sum up the basic ideological battle that has unfolded on the frontier in Laos. To many in the government, the forest is seen as an impediment to development, something that must be removed and then transformed if the country is to move forward. To Western donors and aid organizations, on the other hand, it is a precious and endangered resource that should be used sustainably and maintained largely as it stands now, while giving a significant share of the profits from timber harvesting to the indigenous population.

“Basically, what we are asking them to do is to both stop enriching themselves off logging, which they see as their due, and which constitutes the major source of income for nearly every official in the administration, and at the same time embrace democratic values,” says the American forester. “It seems unlikely that they will ever do either. Fundamentally, it is a difference in values. To us, the frontier is beautiful and unique and should be conserved. To them, it is wild and unmanageable, and needs to be transformed. That is the work of statecraft in their minds.”

Ever since the Pathet Lao takeover in 1975, the strategy for rural development in Laos has been to convert forests into more “productive” landscapes, spearheaded by a policy of resettlement which has forced hundreds of thousands of indigenous villagers to move from their ancestral lands in the mountains down into valley regions. The assumption has been that once these groups learn Lao ways, like intensive wet rice cultivation, and then form linkages to the market, they will be uplifted out of poverty.

But in fact resettlement has been an almost unmitigated failure. In most cases it has produced increased poverty, both material and cultural. One recent study by a French aid group carried out in northern Laos found an increase in all poverty indicators – including decreased food production and increased mortality rates – among a sample of resettled villages. As a result, some government officials, mainly those who are in liaison roles with foreign aid donors, have stated that a new approach needs to be taken.

Privately, however, a different, more Darwinian view continues to be taken. “We see that the resettlement policy is not working for everyone,” a high-level official in the Department of Forestry in Vientiane told me. “But, in fact, it will remain a main element in the development approach we will take in Laos. If you look at it objectively, all it is really doing is implementing through policy what has taken place naturally all over the world throughout history… Societies develop, and as they do, certain ways of living have to be changed, for the good of the whole nation. It is painful in some cases; but sometimes we have to ask our people to starve for a day, to sacrifice, to make the country stronger.”

As the forestry official’s words make clear, the conflict over how Laos should develop is ultimately a clash of values. As one international aid worker in the capital put it, “this is not about science, or anything empirically-based. We can produce all sorts of studies showing how government development policy is bad for people, is even killing people, not to mention opening the door for the plunder of natural resources. But it won’t be effective because, in fact, it all fits into their vision. They look at what the Western donors are proposing for Laos to look like in 50 or 100 years, and they see a country that’s still half forested, mostly inaccessible by road, and populated by indigenous groups that don’t speak Lao, have little to no connection to the government, and who still live off the forest, outside the cash economy. They consider that this would be a major failure.”

The vision of the Vietnamese government and major private sector players, however, is a lot closer to what the Lao leadership has in mind. This approach is articulated best in an economic cooperation agreement called the Development Triangle Initiative, signed by the prime ministers of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. This Hanoi-led plan for the development of several border provinces in the three countries, including Xekong, is essentially a strategy for the conversion of the frontier areas of Laos and Cambodia into vast “forest gardens” that will supply the raw material for Vietnam’s rapidly expanding economy.

As a first step, the primary resources are to be exploited – meaning dams, mines and timber – generating the capital to invest in longer-term projects like tree plantations. Over time, the vision of Xekong will be realized through resettlement and “spontaneous migration” by indigenous communities to jobs in the plantations and processing facilities that will spring up. This is the blueprint for how the frontier will be transformed. The first round, liquidation of timber resources, has already commenced.

[B]ack in Khampone’s village it is hard to sleep. There is still no relief from the heat, and tonight, added to the usual sounds of the frontier at night – the cicadas and owls – is the whine of an old Russian log truck as it winches another stem onto its load. It is the height of the logging season, just before the rains, so the crews work through the night, hauling out logs to a landing some thirty kilometers down an unpaved track that will be rutted four feet deep by the end of the season.

It is also hard to sleep for all the commotion coming from Khampone’s house. A group of village elders is meeting with the Vietnamese logging crew boss, raising the issue of payment. A project supported by an international organization here has been working with Khampone’s village and others in the area to increase their involvement in forestry, and raise awareness about the national legislation that entitles them to clear rights in management and payment. Over the past year, they have learned the market value of what is being removed from their village, and they have calculated what they say they are owed from the previous three years. They are now showing the crew boss these figures, following the new Lao laws which are virtually unknown in villages like this, and which are vehemently opposed by government officials.

The over one thousand cubic meters being hauled out of Khampone’s village this year has a value of approximately half a million dollars, and this just as roundwood – after processing and export it is worth at least twice that amount. The logging boss is explaining that he and the Xekong forestry agency have agreed to pay $1,200 to the village for the year’s operations, noting that this is double the rate paid in neighboring villages. But Khampone and the village elders wave the legislation in front of him, signed by the Lao Prime Minister, and insist that more like $85,000 should be paid. A raucous laugh comes from the house, and the crew boss storms out, shaking his head, back to supervise his team.

As the awareness of villagers in this part of Xekong has grown, so have the conflicts. Last year, a group of minorities downstream from Khampone’s village organized a posse and burned a whole landing of logs waiting for transport to a Vietnamese sawmill. They were protesting the fact that they had not been paid for the timber removed on their lands, and demanded fair compensation, following the law. A few months later, the chief and two deputies from a neighboring village traveled to Lamam town, a two-day walk, to lodge a complaint directly with the Governor, an act of social protest almost unheard of in Laos.

Despite such demands for justice, it seems hard to believe that much will change. A few months after these incidents, the project supported by the international group working with these villages was discontinued by the government. The Xekong government’s official reason was that the project was not authorized to address logging, which is the sole realm of the state. But those close to the project reported that government officials were paid off by Vietnamese wood industry interests to stop the work.

“We supported the work of the project,” says Khampone. “Unfortunately, the government does not like to follow its own laws.”

Author

Credits