Stephen Mansfield interviews photographer Jacqueline Hassink on her 10-year quest to photograph Kyoto's gardens

[A]mong its many distinctive attributes, Kyoto is a city of gardens. These living artworks change with each season, and draw millions of visitors to the ancient capital each year. Most are centuries old; some of the most elegant lie hidden away in temples that are closed to the public. For the past ten years, the internationally-known Dutch visual artist Jacqueline Hassink has been making photographs of some 200 of Kyoto’s temple gardens, that clearly reveal a unique integration of nature, architecture and human culture. Her efforts have culminated in a collection of these photographs, View, Kyoto, which was published earlier this year. She has published many books including The Table of Power 2, which was nominated for the Paris 2012 Photo/Aperture Book Award. She has exhibited at Huis Marseille in Amsterdam; [Fotomuseum Winterthur, Winterthur; ICP in New York;Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Tokyo; the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Guangzhou Museum of Modern Art, Guangzhou.

Stephen Mansfield: There are over 200 listed gardens in Kyoto, and others like the Ueki designs in Nanzenji that you might have gained permission to photograph. What were your criteria for selecting your final list?

Jacqueline Hassink: In the first place my criteria was that the gardens had to be in the Kyoto area, so that is how a temple like Hosen-in became part of the project. As an artist my starting point is different to that of a scientist or a person who creates a book about Japanese gardens—as you can see, the title of the book is View, Kyoto with the subtitle “A study of space and nature.”

Since 1993 I have been interested in the identity of space and how humans create spaces. I also have a general interest in economic power. An example is the series The Table of Power and The Table of Power 2 (published 1996 and 2011) in which I photographed the boardroom tables of the largest corporations in Europe without people being present.

I focused on the meaning of the table as an object and also on boardroom spaces. How do huge corporations project their corporate identity and position of power through one single space and one single object? Private and public space plays an important role as well: where did I get access and where did I not? It is a way of mapping.

In the project View, Kyoto there is something similar going on. I was drawn into the temple grounds because of a unique architectural phenomenon that takes place in Japanese gardens and Buddhist temples. This is why I chose to focus on temples over the myriad of other forms represented in Kyoto; there is no divide between the private and the public realm when one is seated on a tatami mat viewing the garden.

My initial idea was to explore this undefined border between private and public space by photographing the garden from deep inside the temple, balancing the areas of tatami/meditation space and garden space equally in the image.

Over time I developed two other series. One deals with space inside the temple. The head monks of two temples (Shunkōin and Ōbaiin) allowed me to freely move the rice paper sliding doors inside the temple to create new gigantic open spaces. I worked with the material of the temple to create unusual photographic compositions based on sculptural considerations. This working process allowed me to comprehend how architectural space is used in a temple in relation to nature.

The second series focuses on nature. The large moss garden of Saihō-ji (founded in 729) is located far from the main temple. This unique setting shifted my attention from inside the temple to the garden. This garden is covered by 120 types of moss and represents the Buddhist concept of paradise. I visited the garden four times.

Both boardrooms and temples have historically been male domains, and are the products of great wealth. Was accessibility to each equally hard; was one more difficult than the other, and why, and what arguments did you use to gain accessibility?

It is more difficult to get access to the temples in Kyoto than to get access to boardroom tables. Corporations are very structured and organized. They are used to people approaching them. My request to photograph the boardroom as part of an art project was kind of unusual. But in the end I got my answer within several months.

The monks in Kyoto are a whole different world and situation. Kyoto has so many people visiting every year and the monks are approached by many of these visitors. They have nothing to gain from outsiders so would rather not be disturbed in their daily life. Over time when you do connect with them they treat you with great kindness. Several monks have welcomed me again and again to their temple grounds. Keido Fukushima, of Tofukuji, who I dedicated the book to and passed away in 2011 was one of those monks whom I visited many times. We had talks about life and Buddhism while eating sushi and drinking sake.

Could you share with us your reflections on how these two types of space differ in what they express and how they express it? It is interesting, for example, to consider what is on display in these rooms…

Boardrooms are very important to corporations. They represent corporate identity, as I mentioned before, as well as a vision of a company or CEO about economic power. There is a long history in these places and the tables reflect the way the CEO is ruling the organization.

Temple spaces or rooms are completely different. They are more or less accessible to the public and the materials used are all roughly the same. There is no meeting point like a boardroom table, and the gaze is directed toward the outside space or garden. There is a connection with nature that has great influence on the way one experiences the space. While the temples are accessible to the public these defined spaces are also geared towards a more private inner life. One tends to withdraw and contemplate about life while sitting on the tatami.

Garden publishing is quite an industry these days. In what way is your title different?

It is an art project and an artist book. It not only shows the results of a ten-year-long project, but also my personal notebooks as well as two other bodies of work that I created during the same time: the film View, Kyoto and a self-portrait, the maiko as an artist, the artist as a maiko.

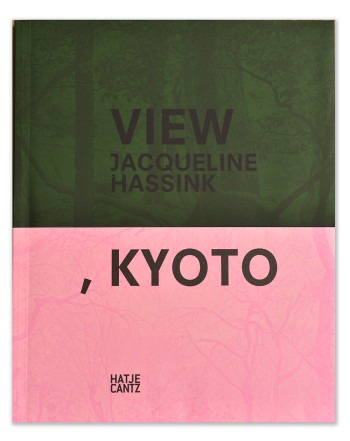

At 28 by 35cm, the book is big. It is designed by Irma Boom, one of the world’s most well-known book designers. All of her books are part of the MOMA collection in New York. This sets View, Kyoto apart from other books out there.

The cover of the book is also quite unusual—it is an American dust jacket with an invention inspired by a Japanese obi. The green part has a touch finish that feels like moss and the pink part is printed on matt paper referring to fresh cherry blossom. You can fold out the cover and it reminds people of origami.

What was her concept behind the design? With so many photographs, what kind of approaches did you discuss?

The concept behind the book was a long process that took months. It is not just one idea but it developed over time. Irma worked on the book with her Japanese studio assistant Akiko Wakabayashi. I remember she thought it was important from the beginning that the book should be big, so that you could really experience the gardens. It becomes more physical. The notebooks were also essential in showing the long process of making the work. Since 1991 I have always kept a notebook with me while traveling. I write down new ideas and things that happen.

Irma wanted to use a coated paper from an Italian mill called tatami but in the end it was too expensive. The idea how to place the photographs on paper is quite important, too. There is either white space on the left side, right side or on both sides. It has all to do with the view of the camera. A photo taken from the left corner gets a white border on the right side and vice versa. A frontal image is framed equally from left and right by white space.

The cover design is something that we discussed towards the end of the process.

The head monk of Ōbai-in Taigen Kobayashi found View, Kyoto to be unique. The way I looked at the gardens and the amount of time I took to develop this project is highly unusual. He was very moved by it.

The book has almost sold out in half a year, which means that other people felt something similar. It won a major award in Germany for best photo book of the year and was reviewed by The New Yorker. Hatje Cantz, my publisher, and I are preparing a reprint.

Did you have a conscious target audience for View, Kyoto?

For the artwork, no. For the book there was a discussion with Ulrike Ruh, Program Director at Hatje Cantz, that it should appeal to a wider audience. The size of the book, the design by Irma Boom and the scans made by Jan Scheffler in Berlin all contributed to this.

Did you have any specific intentions for the way you wanted viewers to perceive your images?

I never think about that. It is an art project created by me, and how the viewer experiences my work is something up to them. At this moment, the book View, Kyoto as well as the exhibition is traveling all over the world. There have been exhibitions in London, Amsterdam, Cologne, Kyoto and New York. It is in this instant that the artwork becomes public domain. It is again a transition piece and I am always curious to see how people react. I hope people enjoy the work. I also hope that they are able to read the interviews with the four head monks as well as Gert van Tonder’s Q&A.

Can you tell us something about the photographic hardware and printing techniques used to achieve these images?

I work with a Pentax 67 II camera and use Fujifilm. We develop the film and prepare the images in New York in my studio. The negatives are scanned for the book in Berlin, and the photographs for the exhibitions are printed analogue in my lab in Amsterdam in the dimensions 127 by 160cm.

How has the great painting tradition of your home country influenced your photography? Is the reason you make exhibition prints large is that you want them to have the impact of paintings?

I am drawn to the work of Vermeer and Rembrandt. I look at these paintings at least four times a year in de Rijksmuseum when I am in Amsterdam. There is something about the light and the space that I like very much. I am sure it has influenced me but I am not sure how. I was born on 15th July, the same day as Rembrandt— maybe there is a subconscious connection.

The reason I make large-scale prints is because I think that the size is really the best for the work. Vermeer’s paintings are small and my museum prints are much larger, 160 by 127cm or 200 by 160cm.

Were you influenced by the work of other photographers, writers and artists in creating View, Kyoto? I’m thinking of people like Christian Tschumi and his work on Mirei Shigemori, and David Hockney’s montages at Ryoanji.

Not really. I was more influenced and inspired by Kyoto and the people that I met like Gert van Tonder, Yasu Suzuka and the monk Keido Fukushima to whom I dedicated the book.

Your images, often taken of interiors and from a kneeling height and perspective, reminded me of stills from Yasujiro Ozu films. Is that a valid comparison?

That is possible. I put the tripod on three square rubber pads as recommended by the monks. I tried to position the legs as low as possible so that the viewpoint is similar to how one views a garden.

You put in a lot of fieldwork for this project. How did this fit in with your other commitments?

As an artist my commitment is to myself and what I want to create. So there is no conflict other than making new work, attending openings of my shows, giving lectures and doing workshops. Very often I work on similar projects at the same time. The Table of Power 2 (2009-2011), Car Girls (2002-2008) and Arab Domains (2005-2006) were all created concurrently with View, Kyoto (2004-2014).

Tell us more about the fieldwork behind the self-portrait, The maiko as an artist, the artist as a maiko. What did you learn from ‘becoming’ a maiko? How did you feel during that experience?

Becoming a maiko is a transformative experience. You are another person and you play a role. I understood how it is to be in that place only by becoming a maiko. The ‘mask’ of the white face is really what does the trick. If your face is painted white you are not the same person anymore. I really liked it and I started to ‘play the role’ as maiko. People on the street in Gion thought I was Japanese. That was quite an incredible feeling.

From your experience, how would you describe Japanese ‘ma’ to a first-year art student? How is it special and what did you learn most about it?

Ma is difficult to explain to people who have not visited Japan before or who haven’t spent a lot of time there. Ma must be experienced. It relates to space and can be physical space but also mental space. I think ma becomes more important in the digital age in which we live.

I would say that in a conversation the moments of silence are ma. These in-between ‘empty spaces’ are as important as words. Americans and Europeans have a hard time accepting this moment of ma between two people, but when it is there without discomfort it is really quite beautiful and meaningful.

Emmet Gowin wrote, “My photographs are intended to represent something you don’t see.” Do your photos attempt to correct that inattentiveness to our field of vision?

For me photography is a reflection of my soul. It is how I experience and look at the world. I am very interested in the world we live in. I travel six months a year all over the world, and in my travels I connect the dots and that is how I am inspired to make new work.

For some people it is hard to understand how I make such different bodies of work, going from boardrooms to Buddhist temples, photographing Car Girls in Frankfurt, businesswomen in Yemen and ending up on the island of Yakushima. For me it makes sense because it is all created by me.

You’ve mentioned that you want to photograph temple kitchens next. Can your tell us a little about that project and what you’re working on at the moment?

I am working at the moment on a major project called Unwired Landscapes. By this I mean places in the world unconnected to the Internet and without cell phone reception.

The project I am considering on kitchen temples contemplates places where monks practice meditation, and how gardening and cooking can be ways to practice zazen. I envision it as a connecting series to View, Kyoto.

Stephen Mansfield is a British author and freelance photo-journalist based in Japan. He has lived and worked in, among other places, London, Barcelona, Cairo, and the south of France. His work has appeared in over 60 magazines, newspapers and journals worldwide, including The Geographical, South China Morning Post, The Middle East, Wingspan, Japan Quarterly, Travel Plan, Critical Asian Studies, and The Japan Journal. He is also the author of Japan: Islands of the Floating World, the Insight Pocket Guide to Tokyo and Eyewitness Travel Guide Tokyo (Dorling Kindersley). Tokyo: A Cultural And Literary History was published by Signal/OUP in 2009. Top 10 Tokyo came out in November 2009. Japanese Stone Gardens: Origins, Meaning, Form appeared in 2010. His next history book, Tokyo: A Biography, will appear in the spring of 2016.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013