Ken Rodgers interviews Frank Stewart & Patricia Matsueda of Mãnoa, on expanding cultural horizons

“The translator’s work is more subtle, more civilized than that of the writer: the translator clearly comes after the writer. Translation is a more advanced stage of writing.” —Jorge Luis Borges

“A translation can only complement, not replicate, the original.” —Howard Goldblatt

“Horace was the first to warn against verbo verbum translation. Octavio Paz notes, ‘Every poem is a translation.’ With roots in Greek, Latin, and German, and with an admixture of foreign terms that have become Americanized through common usage, the English language itself is a translation.” —Sam Hamill, ‘Sustenance: A Life in Translation,’ The Poem Behind the Poem

“The whole practice is based on paradox: wanting the original leads us to wanting a translation. And the very notion of making or using a translation implies that it will not and cannot be the original. It must be something else.” —W.S. Merwin, ‘Preface to East Window: The Asian Translations,’ reprinted in The Poem Behind the Poem

“The translator must first be a medium between the natural and human worlds, between the living and the dead, and among cultures, languages, and peoples. The translator of poetry must also be a historian, a linguist, a magician, a composer, an intuitionist, a lover, and a midwife, but most of all, he or she must be a poet.” —Leza Lowitz, ‘Midwifing the Underpoem,’ The Poem Behind the Poem

“To make a Chinese poem in English we must allow the silence to creep in around the edges, to define the words the way the sky’s negative space in a painting defines the mountains.” — Tony Barnstone The Poem Behind the Poem

[T]he Hawaiian word ‘mãnoa’means “vast and deep,” and is a literal description of the lush green valley on O‘ahu that is home to a unique bi-annual publication of the same name. Mãnoamore than lives up to its derivation, through its vast and deep coverage of contemporary writing. Frank Stewart, editor, and Patricia Matsueda, managing editor, make excellent use of their central location on the hemisphere-wide radar screen of the blue Pacific to sweep the surrounding Rim and its hinterlands — and the island nations in between — searching out the most vibrant and engaging contemporary literature, much of it appearing for the first time in translation. Over the years they have garnered dazzling collections from traditions as diverse as Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, the People’s Republic of China, Tibet, Korea, Aotarea (Maori New Zealand), Malaysia, Nepal, the Pacific islands, Japan, Cambodia, Viet Nam, and Taiwan. These are presented either in unified anthologies based on a nation or cultural group, or in volumes of diversely mixed new work from throughout the region, including the Americas, creating a stimulating intercultural dialog.

Ken Rodgers visited Mãnoa in early December 2004, just after Frank had hosted a special evening performance by Cambodian rapper praCh, who was featured in Mãnoa’s summer 2004 collection, In the Shadow of Angkor: Contemporary Writing from Cambodia.

KJ: Frank, how did Mãnoa get started?

FS: In the late 1980s, when the state’s economy was booming, the University of Hawai‘i decided that journals were important, and that there was room for a few more here. So the administration asked interested faculty to propose ideas for new journals, and those selected would then be subsidized for three years to get them off the ground. My friend Robbie Shapard and I proposed a contemporary literary journal with an emphasis on work from Asia, the Pacific, and the Americas. We wanted to create a journal ambitiously beautiful and large, and if we couldn’t maintain the quality and size after the initial three-year subsidy, we would at least have tried to do something extraordinary. Our proposal was accepted, and in 1989 our first issue was published through the University of Hawai‘i Press. Robbie was editor, I was associate editor, and Mãhealani Dudoit, a student, was our managing editor. Robbie’s background was in mainstream American writing, and my interest was more in Asia and the Pacific. So in our first issue I think we had Ann Beattie and Joyce Carol Oates — authors like that — plus new Chinese fiction selected and translated by Howard Goldblatt. It was great to be mixing East and West together, and in the beginning our contents page didn’t even identify which author was from which country; we thought we would just stir all the authors together and see what kind of salad it made. The result was well received. No other literary journal was attempting anything quite like it. Robbie stepped down in 1995 to pursue his own writing, leaving me — with the help of Pat Matsueda, our first full-time managing editor, and a crew of part-time student assistants — to keep the project going. By this time, we had developed many contacts in Asia and the Pacific and were in an even better position to seek out international authors and translators. The following year, we began to give greater emphasis to translation, and we also redesigned Mãnoaso that it could be sold as a book as well as by subscription. The first in this new series was Seeing the Invisible , featuring Korean women fiction writers of the post-democracy period, guest edited by Bruce Fulton. Before we began production, we convened a workshop in Seoul, with a grant from Samsung Foundation, which brought the authors and translators together face-to-face. Mãnoa’s mission increasingly became defined as “seeing the invisible,” as we focused on publishing superb non-Western authors, most of whom were simply “invisible” to American audiences because embarrassingly few books of literary translation are published in the U.S. In this same spirit, we’ve published volumes focusing on Tibet, Indonesia, Nepal, Cambodia, and elsewhere.

Pat, how did you get involved here?

PM: I started working here in 1992, but before that I was a volunteer. I’ve seen the journal change a lot in these 12 years. When I joined the staff, we had one room, a PC with a 286 microprocessor, and a small table that I used for a desk; I sat on the couch and worked at the table. Now we have real desks and several Macs, we’ve put out over thirty book-sized issues, and something like three or four dozen staff members have come and gone. I was the journal’s first full-time staff person, and we’re hoping to add another full-time position soon. I think I’ve changed too. Working with several hundred authors on their pieces, reading and editing work from all over the world — this has changed my thinking, even who I am. In fact, I would say I am no longer the person I was when I started.

Among all these issues from different places, different social contexts, do you have a favorite?

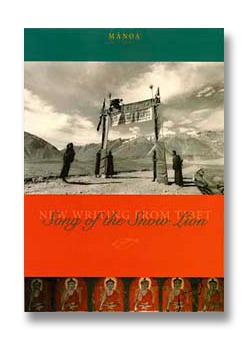

FS: Each issue is singular and develops its own power over us as we become immersed in it and develop relationships with the authors and translators. I’m reluctant to have to choose. But I’d have to say I’ve been deeply moved — spiritually, intellectually, artistically, etc. — by editing recent volumes on Indonesia, Tibet, and Cambodia; and on Korean American immigration. For example, when we started to compile the work of Indonesian writers for Silenced Voices, guest edited by John McGlynn, the Suharto dictatorship was still in power. Nearly all the Indonesian authors we chose had suffered terribly under military rule, and their works had been censored in whole or in part. Just as we went to press, the first democratic elections in over four decades were being held. With funding from the Ford Foundation, we were able to cosponsor an American tour by three Indonesian authors. In our volume of Tibetan writers, Song of the Snow Lion , similar issues with censorship were at stake. For In the Shadow of Angkor , guest edited by Sharon May, we were able to translate for the first time some of the excellent Cambodian writers who were killed or exiled by the Khmer Rouge regime, and to publish some younger Cambodian American writers as well. Becoming so familiar with Cambodia’s devastating journey through genocide — and the resiliency of the Cambodian spirit today — can’t help but alter you.

PM: For me, a favorite issue is Silence to Light: Japan and the Shadows of War , which is all about Japan in WWII. A few of the pieces come from that period, and others were written afterwards. That is one of the most important issues that we have done, because the subject of the war is so large, complicated, and emotional. Japan’s behavior during WWII was really abominable, but if you read Silence to Lightfrom cover to cover, you’ll see that the pieces arouse a lot of sympathy for the Japanese. They were victims of war too. Nicholas Voge’s translation of a group of letters written by kamikaze pilots to their families was reprinted in two British newspapers and in ITALICS Harper’s magazine. Soon after 9/11 happened, we were contacted about reprinting them. I think people found those letters of great power and relevance.

I guess that your family was originally from Japan?

PM: Well, I was born in Japan, on an air force base in Kyushu. My father was a sergeant in the U.S. Air Force, and he married a Japanese national. I came to Hawai’i shortly after they were divorced, as his parents wanted us kids nearby.

Have you revisited Japan since then?

PM: I haven’t, but for a long time I felt that was where I belonged. We were very poor, so I grew up outside the mainstream, and I always had an outsider’s point of view. Silence to Light for me brought together so many things — it made things cohere for me on a psychological and spiritual level, even geographical level. I think that is one of the most important things that Mãnoacan do — it allows you to live the lives of other people, to experience their histories and fates. It changes what you think of humanity, life itself.

How do you actually go about creating an issue – from selecting a theme and finding translators and a guest editor?

FS: An issue might begin because there is a country we’re interested in, and we go looking for a guest editor who knows about that country. In other instances, we call upon editors we’ve worked with before, and ask them if they’ve got something they’d like to develop. Often, serendipity has a role. For example, the guest editor for In the Shadow of Angkor, Sharon May, is someone I happened to meet briefly at a conference in Portland. She later wrote a story for us called “Kwek,” which was set in Cambodia and received an honorable mention in the O. Henry Prize anthology of best American fiction in 2000. I think she was returning to Cambodia soon, and I off-handedly asked her to keep a lookout for what was happening in regard to literature there. She said “sure,” and we corresponded a bit by e-mail. At the time, I was doubtful there would be enough material from Cambodia to fill a volume, so I had in mind to include Burma and Thailand as well. In early 2001, Sharon was in Southeast Asia and had begun actively searching out Cambodian writers. So in March, after more e-mails between us, I just asked her to guest edit a volume on Cambodia. I didn’t know her well, and she was a little tentative too. But she turned out to be the perfect person for the task. She threw herself heroically into a project that eventually involved making contacts on several continents, translating from various languages, tracking down leads. I think neither of us could have foreseen how difficult the project would be — nor how rewarding. Sometimes things happen by accident. With Silence to Light we approached Leza Lowitz, with a general idea about an issue on Japan. She is always interested in work out of the mainstream, so we knew that she would come up with something wonderful. She started work, and she did come up with some very avant-garde, exciting, interesting stories that are not what one would expect from Japan. Tentatively, she suggested we gather stories around the theme of “family.” I realized that we were approaching the fiftieth anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, just as I realized that many of the pieces Leza had found were somehow related to the Second World War, from an Asian perspective. This was a perspective I knew that Americans would not get in the media attention that would surround the anniversary.

PM: Leza worked on two Japan issues. The first that she worked on, published in summer 1995, contained what she called — borrowing the phrase from Kenzaburo Öe — “a literature of the periphery.” For example, there’s a story called “The Pepper Tree,” written by Hiromi Ito, which challenges traditional Japanese ideas about home, family, insiders and outsiders. Another story, “I Want to Be Holding the Sea,” is by avant-garde writer Ango Sakaguchi. It’s very moody, dark, strange. For Silence to Light she was gathering material concentrating on the family in Japan, and then as Frank read those pieces, he realized that the war was the central thing…

FS: Then I said, “Leza! Let’s drop all that, and do this other idea.” And she said, “Okay!” She did a brilliant job. You start out with nothing, and you think you know where you’re going, but…

PM: You start with individual pieces, and then you find that you are telling the story of a whole nation, a story that has never been told. It was when we were working on Silence to Light that I realized how terribly the Japanese had treated the Chinese and Koreans. It really made me feel ashamed. And when we worked on Century of the Tiger [100 years of Korean Culture in America 1903-2003], I had the chance to work with Jenny Foster, who’s a Korean adoptee — she was adopted by a family in Michigan. It was a chance for us to work on healing what had happened between our countries, even though we hadn’t been born at that time and we had nothing to do with those events. But some healing between Korea and Japan took place through us. When I was helping Frank to train the docents, the volunteer guides, for an exhibition at the Bishop Museum that was tied to that issue, one of them was a Korean man who had suffered a great deal under the Japanese. At the training session, he expressed all his hurt. My response was something like, “I don’t think any Japanese with awareness of those deeds can refrain from feeling shame and guilt, but if you combine that sense of shame and guilt with a sense of responsibility and obligation, you get Century of the Tiger.” FS: The exhibition at the Bishop Museum was an example of the way we try to create community response around each issue of Mãnoa. The wisdom and insight of great stories and poems are never just for the pages in a book, but must be released into a larger setting involving communities of people.

I was impressed to see that probably a hundred people from the local Cambodian community came out for praCh’s performance, in which he used rap to focus on post-holocaust Cambodian identity. They obviously saw value in what he is doing…

FS: praCh’s performance was another example of how we like to use publication as a means of bringing people together. Publication is only a small part of what we understand our mission to be. As much as we love the volumes we produce — the design, the art, the beauty of the language — community-building and raising awareness are the other activities that keep us going and the energy flowing. We know that many people will not buy a copy of the journal, but we still want them to know something about what’s inside, what the content reveals about the world and how it is relevant to them.

Kyoto Journal’s “perspectives on Asia” are very much a product of our home environment, Kyoto, being a kind of cultural crossroads. Do you see this applying to Mãnoa, as well?

FS: Oh, absolutely. I think one of the reasons no other American publications have done this is because of location. Hawai’i is primarily an Asian and Polynesian place, with a minority of Euro-Americans. It is very distinct from the U.S. mainland — culturally, geographically, and historically. People who have lived here for a long time have a different mindset. We are nearly as close to Tahiti as to San Francisco, and closer to Shanghai than to New York. And everyone here is part of a minority. We bring a different sensibility to the international situation.

PM: We say in our applications to the National Endowment for the Arts that one of the things we want to do is make Americans more aware that part of their heritage has an Asian-Pacific aspect, and we want people from those countries to be aware of that aspect and to feel proud of it. praCh was already on that road, and he happened to intersect with us. There was one interesting thing that happened at his performance. Some of the people buying In the Shadow of Angkor were very hesitant; they were not used to reading books, and they weren’t sure what value it might have. What praCh said at his performance made them see that by reading the book, they could re-experience what he was sharing about Cambodian culture and history.

I liked how he said that he felt most proud not of being in Newsweek or having a number-one hit song for three months in Cambodia, but for having stimulated students to ask questions of their professors, and teachers to ask for more books to be put into the libraries there.

FS: The Cambodian community here is quite small; a sizeable percentage may have been at the performance, I don’t know. But they are in a sense an invisible minority, even in this predominantly Asian-Pacific place. Our intention in producing In the Shadow of Angkor was not only to show Americans that Cambodian culture is alive and growing, but also to show our local community that there are Cambodians here, and that they have brought their heritage, their history, and their culture with them. This heritage is, as Pat says, now part of America.

In looking at different regions in Asia, are there any concerns among writers that seem to be shared?

FS: Well, just one example is Nepal. We had wonderful guest editors, Samrat Upadhyay, who lives in the U.S., and Manjushree Thapa, who lives in Kathmandu. They are very sensitive to the writing community in Nepal and were able to gather stories and poems that show many aspects of the artistic situation. For all the cultural differences between Nepal and other places, we were surprised by how similar the central questions are: who gets to speak and to be published, who gets listened to, how are minority languages treated, how should one deal with the tension between tradition and modernity. Those issues are really everywhere.

PM: And whether literary experimentation is Western or part of the tradition of that country. That’s another thing that comes up in the Nepal issue.

We usually think of literature as about individual expression, within the writer’s own cultural context. Do you see any essential Asian characteristic that seems to contrast with Western writing?

FS: We encourage unsolicited work, and we get thousands of submissions yearly, mostly from American writers. Unfortunately, we find that the vast majority seem to be — I hate to say this — mostly about nothing. By which I mean, the writing tends to be solipsistic, domesticated, stylistically safe, and artistically lacking in ambition. This is a big generalization, I know, and I don’t mean to say that good writing will always be the opposite of these things. But writing can, and therefore must, engage us completely — intellectually, emotionally, physically, spiritually, morally, and with an expressiveness that feels alive and somehow inevitable. Now I’m sure there’s also a lot of Asian writing about nothing, but because Mãnoa is able to look outside the boundaries of America and of the English language, we can draw work from a much larger pool than many other journals can.

‘World music’ has become a genre. Do you see any possibility of an equivalent in ‘world fiction’ or ‘world poetry’?

‘World music’ has become a genre. Do you see any possibility of an equivalent in ‘world fiction’ or ‘world poetry’?

FS: I see a lot of American influence on the poetry and fiction of other countries, and I fear there is not enough influence going in the other direction. I was at a conference last month in Boston, at Simmons College, and we talked about this quite a bit in regard to Chinese poetry, in the PRC, Taiwan, Singapore, and elsewhere. Taiwanese poetry has been beautifully translated by Michelle Yeh and a few others — and because it is a hybrid of so many influences and is very volatile and exciting, there is a lot that American writers could learn from it. Likewise contemporary PRC poetry can be very daring. I regret that this energy and innovation are not reaching more American readers and writers. Through translation, that is. As you know, Chinese and Japanese poetry, by way of Pound, has had a great influence on several generations of American poets. Pound turned to Asian poetry as a way of overcoming the deadness and exhaustion of late Romantic and Victorian poetic mannerisms. Americans could gain much by following his example, looking to international poetry for fresh ideas and inspiration.

It’s also interesting to see praCh realizing the essential emptiness of gangsta rap, and investing it with something else, Cambodian history, and making it big back in Cambodia…

FS: Very much. Hip-hop is world music, and changes as it travels and is absorbed by local traditions and taste.

You deal with translation year in, year out, spending up to three years on an issue. What is translation, to you?

FT: Well, as an editor, it is very important to me that if we do an issue concerning a non-Western country, that what we publish be as excellent as it can possibly be so that the reader becomes engaged by the country’s writers and wants to read more. We want to help place the work of the country’s writers in the context of international literature, and that requires an insistence on a very high quality. We could fail by not finding the right authors, or by not finding the right translators. So we try to be very thoughtful.

You have a great quote here in your recent groundbreaking compilation of translators on translation, The Poem Behind the Poem, saying that “the worst infidelity is to pass off a bad poem in one language as a good poem in another.” How do you monitor the quality of translations?

FS: We go back and forth a great deal with our translators, as we do with all our writers. We copy-edit very closely, trying our best to understand “the poem behind the poem.” We might go back to the translator and say, “Would this be an equivalent?” or “Is this an improvement, or are we distorting it?” We have an intense working relationship with translators in whom we already have a lot of confidence. An editor is a servant to the translator as well as to the author and the reader — not a slave but a servant, and we have to bring everything we have to the task. Translation in many ways is impossible, and we all recognize that. Each work has its own challenges that are, in particular respects, insurmountable. But as Robert Bly once said, you may come across something in another language that’s so wonderful, so beautiful, that you’d rather have a bad translation of it than none at all. There’s a lot that one could argue with about that, but perhaps some wisdom in it too. And we have the example of Rilke — the most nuanced of poets — giving his Elegies to his Polish translator to do whatever he wanted with them, because Rilke believed there was something “unsayable” at the heart of his work, and these unsayables were just as unsayable in Polish as in German. Translations add to the store of possible human responses to existence, and it’s silly or arrogant to think that all of these possibilities can be expressed in a single language or language group. Even if a translation from, say Nepali, into English does not convey everything of the original, nevertheless a kernel of it may cross over that, without the attempt at translation, would otherwise not reach us.

PM: A corollary of that idea is what writers who write in English as a second language can show us. Our issue Century of Dreams contains Filipino writing, and a lot of that material was originally written in English, because English is a second language in the Philippines. I really felt that if the American writers published in that issue had read the Filipino work carefully, they would have been awestruck by it because Filipino English is so beautiful, so graceful and intelligent. So I think we are also trying to expand American writers’ idea of literature and language. And if they read translations, they will have a sense of what’s possible, a sense that they won’t have if they only read American fiction. I know that’s true for me now. Some of my favorite writers are Filipino, Tibetan, Malaysian… I love Ge Fei, Ma Yuan, Soth Polin, Kiyoko Murata, Ramón Sunico, Cesar Ruiz Aquino, Ch’oe Yun, Tashi Dawa — just a fraction of the writers I think of when I think of the best work we’ve published. There’s a conference in Vancouver in March, put on by the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, a national program. I proposed a panel for it called ‘Writers, Editors and Translators As Cultural Representatives.’ What I want to talk about is the responsibilities that writers, editors and translators have when they represent, or render, non-Western cultures to Western readers. I think this idea of responsibility is very important. The flip side of that is, how responsible are Americans willing to be when it comes to trying to understand the world they live in? Given the current politics of the U.S., I think that worldview is really shrinking, so what Americans want to experience in the world will depend a great deal on their own desires, their drive and energy.

What other sources are there for Western readers to gain that vital experience of other cultures?

FS: There are many admirable ones, and we are seeing more translation journals, literary journals in the US focusing on translation recently. That is a good sign, I think.

PM: I can think of one right now: the Center for Art & Translation, which is in California. They publish a journal called Two Lines

FS: There’s also Hyperion, in New York, which has a history of publishing censored writing from Viet Nam, Indonesia, and other Asian countries. Also, I recently learned about Poetrysky, the first bilingual poetry web site publishing both English and Chinese versions of poetry. It was founded recently by Yidan Han, a Chinese poet based in Providence, Rhode Island.

I especially like this idea of creating a greater awareness at a time when America in particular, and the whole world, needs to be more aware of other cultures.

PM: I think there is this idea in the U.S. that is very bad, and it seems to be gaining more believers, that the American way of life is all that you need in order to exist in this world. Just think American, and buy American and be American, and you’ll be fine. I think that’s ridiculous. I think it could lead to self-destruction in the end. I would say you need to read the Filipino writers, the Malaysian writers, the Japanese writers. You need to experience what they’ve experienced, you need a larger sense of humanity — something that a single language or nation can’t give you. Here in the U.S., there has to be a force that’s expanding outward, that’s reaching toward other countries and cultures. Mãnoa, in its very quiet way, is trying to be part of that force.

Ken Rodgers is Kyoto Journal’s Managing Editor.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013