Page Contents

When I first started translating Notes of a Crocodile, I showed a draft to a friend from Taipei who once worked as a journalist and had read one of Qiu’s novels for her research. She couldn’t remember exactly what the book was about, she told me, but when she was cleaning out her apartment, it occurred to her that she should donate her copy. But then she hesitated. She didn’t think it was a good idea to donate a book that might not be a positive influence on teenagers.

Notes of a Crocodile is not a book that shows teenagers how to live a straight life, in any sense of the term. And yet it is intended to be a survival manual for teenagers, for a certain age when reading the right book can save your life. The author lived as an outsider. She went to the best private school, got into the best university. She started writing. She became the first writer in her society to come out as a lesbian. Then she escaped and started a new life on the other side of the world. And then, in the final act, she threw her life away. A suicide. All of these circumstances are inseparable from her heroism. These survival lessons are intended for adults, too, for whom comfort and security come at the incremental cost of individuation, for there will be recurring moments when one feels as though life has yet to be lived, and the truth is, certain mistakes are better than nothing.

Nobody wants to read morality plays anymore, but a lot of people still want to know how to live. And when you want to know how to live, you study great lives, you read Plutarch. But heaven also lets in a few dark stars, and it is best to be exposed to this fact while one is impressionable or has a tall stack of chips sitting on the table. Freedom of speech is based on a degree of faith in the noble potential of all individuals, whose ethical development cannot take place under strictly controlled social conditions. The higher self does not follow orders. It obeys a more mutable and sensitive thing known as conscience, which must be entirely cultivated on the level of the individual. This notion underscores the extraordinary loss in the recent passing of American publisher Barney Rosset in February last year. As the founder of Grove Press, he made an enormous contribution to our shared ethical imagination by offering examplars of beauty and moral complexity through the medium of literature, and moreover, providing access to the rest of the world through the English language. Elsewhere in the world in 1987, a young Qiu Miaojin was just graduating from high school, and during that magical summer, Taiwan revoked martial law after 38 years. It was an opportune time, if you had the courage and the experience as a writer, to come of age and speak your piece.

Qiu is what you’d call a writer’s writer, usually someone you read because you love to follow the motions of his or her voice. Her prose reads like non-fiction, a genre which is, above all else, about cultivating a style. It lays out its own aesthetic blueprint, a constellation of writers and filmmakers of real spiritual conviction and of real artistic risk, a somewhat reserved school of thought which answers a work’s own call to necessity, knowing that whether it succeeds or fails, it all looks the same from above. The epigraphs on the first page of Notes of a Crocodile are entirely made up, but they clearly indicate what gifts she wanted to receive from her literary forefathers who, in this case, are all giants of modern Japanese fiction. From Dazai, something erotic and personal. Not quite autobiography, yet impossible to separate the author from the story. From Mishima, the most beautiful writer in the language, easily the mightiest pen. Burn his biography and perfect artistry will survive in his works regardless. From Murakami, a brand-name degree that means nothing unless you can communicate with the general public. The easier the sentence, the further it will travel. These are all aspects of a single persona that come together organically, exquisitely in the voice of a young woman writing in Chinese. At the same time, there’s a bit of swagger in the mouth. Partly a natural boyishness, partly the college kid talking, and partly the mature writer who openly flouted linguistic conventions and boundaries. This motif can be found again in her last novel, which takes its epigraph from “Amor,” a story by the Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector. Hers is a voice that deliberately carves its own mannerisms and inflections into the language.

It takes an unfamiliar voice, if sometimes a damaged one, to reveal something of humanity to itself. I imagine that a translator ought to approach a literary composition in much the same way that a musician approaches a score, namely with performance as the object. When you pick it up and read it for the first time, which reaches you first, the sound or the meaning? If you manage to capture the sound, the meaning is likely to arrive on its own. It seems a tad unnatural to try to figure things out in the reverse order, since the former emphasizes knowledge and the latter technique. In an interview, Gregory Rabassa confessed that he translated Julio Cortazar’s Hopscotch without reading it beforehand, simply doing it as he went along. The highest beauty lies in improvisation, a blindness of technique in which a battle is played out between one’s individual gifts and absolute faith. It requires fidelity to style, as well as true stamina. Some would call it living by your wits, an instinctive state of being that cannot be taught. But thankfully, it can be put into fake manuals for teenagers, and it can be translated.

Notebook #1

1.

July 20, 1991. Picked up my university diploma at the service window of the registrar’s office. It was so big I had to carry it with both hands. I dropped it twice walking on campus. The first time it fell by the sidewalk, into the mud. I wiped it off with my shirt. The second time the wind blew it away. I chased after it ruefully. All the corners were bent. In my heart, I held back an embarrassed laugh.

When you come visit, will you bring me some presents? the Crocodile wanted to know.

Very well, I’ll bring you some new handmade lingerie, said Osamu Dazai.

I’ll give you the most beautiful picture frame on earth, would you like that? said Yukio Mishima.

I’ll plaster your bathroom walls with copies of my Waseda degree, said Haruki Murakami.

And that’s where it all began. Enter cartoon music (insert the closing theme to Two Tigers).

Forgot to return my student ID and library card, but didn’t realize it. At first I’d actually lost them. Nineteen days later, both were anonymously returned to me in an envelope, instantly transforming their loss into a lie. But I couldn’t stop using them, either, just out of convenience. Also didn’t take my driver’s exam too seriously. Took it four times and failed, although two of those times were due to factors entirely beyond my control. What’s even better, I publicly claim to have failed only twice. Whatever, I don’t care…

Locked the door. Shut the windows. Took the phone off the hook and sat down. And that’s how I wrote. I wrote till I was exhausted, smoked two cigarettes, went into the bathroom and took a cold shower. Outside were the torrential winds and rain of typhoon season. Halfway undressed, I realized there was no soap left. Got dressed again. Emerged from the bedroom with a bar of soap, then climbed back into the shower. That’s how it is, writing a bestseller.

With soap in hand, and the sound of late-night radio in the background. There was a sudden clatter, as if a fuse had blown. I was enveloped in silence and pitch darkness. The power had gone out. Nobody else was around, so I ran out of the bathroom completely naked, searching for a candle without so much as a lighter. Carried three tiny tealights with me into the kitchen, stumbling into an electric floor fan along the way. Tried to light them on the gas burner, but the wax instantly melted down to the very bottom. There was nothing left to try. I threw open the door to the balcony and stepped outside to cool off. I hoped I would catch a glimpse of other kindred souls standing naked on their balconies. That’s how it is, writing a serious literary work.

Even if this is neither popular or serious, at least it’s sensational. Five cents a word.

It’s about getting a diploma and writing.

*

2

In the past, I believed that every man carried in him the innate prototype of a woman, and that he would love the woman who most resembled this prototype. Although I am a woman, I also share this prototype of a woman.

My prototype of a woman was the type who would appear in hallucinations at the last moments of your freezing to death at the top of an icy mountain, a mythical beauty who blurred the line between dreams and reality. For four years, that’s what I believed. And I wasted all of my university days—during which I had the most courage and honesty I would ever have towards life—because of it.

I don’t believe it anymore. It’s like the impromptu sketch of a street artist, a little drawing taped to my wall. When I finally learned to leave it behind, I gradually stopped believing it, and in doing so, sold an entire collection of priceless treasures for next to nothing. It was then that I realized I should leave behind some sort of record before the entire vial of my memories ran dry. I knew that these feelings would vanish one day, as if they had been only a dream, and that the list of what had been bought and sold—and at what price—would never be recovered.

It’s like a two-sided warning sign. The back says: Don’t believe it. The front says: Wield the axe of cruelty. It dawned on me one day, as if I were writing my own name for the very first time: cruelty and mercy are in fact one and the same. Existence in this world relegates good and evil to the exact same status. Cruelty and evil are but natural, and together they are endowed with half the power and half the utility in this world. As for the cruelty of fate, it seems, I have to learn to be crueler if I’m to become the master of the situation.

Wielding the axe of cruelty against life, against myself, against others. It’s a rule that conforms to animal instinct, ethics, aesthetics, metaphysics—and is the axis of all four. And the comma that punctuated being 22.

*

3

Shui-Ling. Wenzhou Street. The white bench in front of the French bakery. The #74 bus.

We sit at the back of the bus, the aisle between us. Shui-Ling and I occupy the window seats on either side. The December fog is sealed off behind a layer of glass. Dusk starts to set in at six. Taipei is now devoured in a sea of black. Traffic creeps along Heping East Road. At the outer edge of the Taipei Basin, where the sky meets the horizon, is the last wedge of a dark orange sun whose natural radiance floods through the windows and spills onto the traffic behind us, as if the blessing of some mysterious force.

Silent, exhausted passengers pack into the aisle, heads hanging, bodies propped against the seats, stone oblivious. Through a gap between their draping winter coats, I peer over at her, trying to contain the enthusiasm in my voice.

“Did you look outside?” I say in my most ingratiating tone.

“Mmm,” comes her barely audible reply.

After a light pause to frame the moment, Shui-Ling and I are sitting together in that hermetically sealed bus. Through the windows around us, the dark silhouettes of human figures wind the streets in a magnificent night scene, gorgeous and restrained. The two of us are content. We look happy. But underneath, there is already a strain of something dark, malignant. Just how bitter it would become, we didn’t know.

See more, at the Brooklyn Rail’s In Translation site.

And here, at The Margins

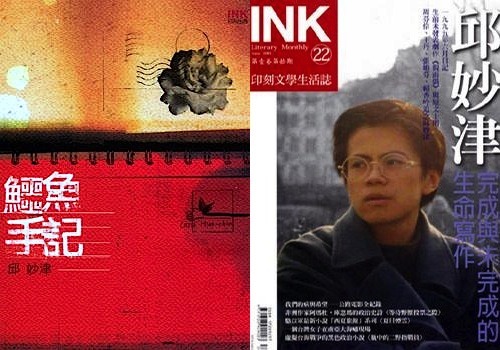

Qiu Miaojin (1969-1995) was a Taiwanese novelist. In 1995, she was awarded the China Times Honorary Prize for Literature. Her works garnered mainstream attention and critical acclaim for their queer politics, countercultural ethos, and international scope of artistic influence, ranging from European cinema to modern Japanese literature. She was educated at National Taiwan University and Université Paris VIII. She committed suicide at the age of 26. A two-volume set of her diaries was published posthumously in 2007.

Bonnie Huie is a writer and translator. She was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and educated in the US and Japan, and she has also lived in Germany and the Czech Republic. Her translation of Qiu Miaojin’s Notes of a Crocodile, for which she was awarded a PEN Translation Fund Grant, is forthcoming from New York Review Books.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013