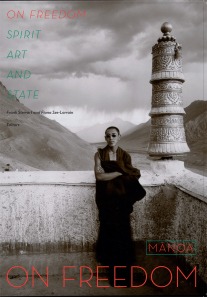

On Freedom: Spirit, Art, and State (Manoa, Volume 24 number 2). Edited by Frank Stewart and Fiona Sze-Lorrain. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 200 pp., $20.00.

[A]s I sat down to read On Freedom: Spirit, Art, and State, one of the first thoughts I had was how difficult it is to peg a term as loaded as “Freedom.” At about the same moment as I had this thought, the chorus of the jaunty Calypso song on my stereo sang out, “Always remember somebody suffering more than you.”

This was absolutely fitting, as the word “freedom” rings hollow when said by people who actually have it, particularly when said in my own American vernacular. The freedom sought in this volume published by Manoa goes beyond the political, and even beyond the freedom of spirit, art, and the state, as promised in the title. Within this book’s pages, we find freedom in memory; in “dreams”; in escaping; in not knowing.

So far be it for me to define freedom, for as the book itself states,

the various meanings of freedom are difficult to clarify in the discursive language of theory and philosophy. But authors of fiction, poetry, and other narrative forms—using metaphor, parable, and figurative speech—are often at home with what is difficult and too subtle for reason alone. Residing in countries throughout Asia and North America, the authors in On Freedom help us understand the need for cultural, spiritual, and intellectual freedoms in order to have a life that is fully realized.

The publication is more formally referred to as Manoa: A Pacific Journal of International Writing. This award-winning literary journal was first published in 1989 through the University of Hawai‘i Press. Mãnoa is a Hawaiian word meaning “vast and deep,” a pair of adjectives that could best describe each issue, highlighting as it does American, Asian, and Pacific fiction, poetry, essays, plays, and artwork. Often publications that cast such a broad net tend to include one or two pieces that were better to have been thrown back, but Manoa consistently publishes the best work of award-winning writers and artists of great renown. There’s a vitality in the voices of the writers and poets in this particular volume, often because they’d lost their physical freedom. Judging by the strength of the writing, their thoughts had continued to roam ever free.

Living as I am in Japan, I was of course most drawn to the Japanese writers. Mutsuo Takahashi’s story, “The Snow of Memory,” expresses the freeing tendency of memory, as the main character attempts to conjoin the woman who returns to him after the war with memories of the mother she once was. In the story “Visitation” that follows, Sukrita Paul Kumar examines escape as freedom, in this case escape from a woman who stalks him in dreams. Later, Andrew Lam’s emotional “Step Up and Whistle” examines the freedom that comes from escaping an identity bound by family.

As many of the contributors originate from countries with particularly repressive political regimes, escape is a common theme. This includes Woeser’s “Garpon La’s Offerings,” the story that I personally consider to be the centerpiece of the book, coming ironically midway through the 180 page volume. It is a riveting story and one of the best written, telling of the long imprisoned Garpon La, who is the sole master of a certain Tibetan performance ritual. His story shows the importance of freeing ourselves from our own intentions. Then again, intent may be all we’re left with, as demonstrated by the final story in the book, Jose Y. Dalisay Jr.’s “In the Garden,” where Mr. Pareja must protect the children in his care from a roving band of guerrillas.

It is inevitable that all anthologies, even those centered on a single theme such as this one, are bound to contain a great deal of diversity. This is inherent in the quote above with which I closed the third paragraph of this review. Yet what is equally inevitable is the freeing tendency of story itself, perhaps not necessarily for the characters within the story itself, but certainly for those who create them. As stated by Phil Choi in his “Choosing Burden,”

Arranged marriages. Lost children. These are the stories that attend the movement of our generations through history. The empty spaces are slowly being filled in, but there are so many of them. I am an American, among the first of my family born outside Korea. Disconnected and without memory, I grope my way among these tales, not sure what belongs to me and what I should not touch. Stories run away, hand-in-hand with time, and change even before they are told.