[U]nlike many writers on Japan, Donald Richie advances no social theories. He has, after all, made the country his home for more than fifty years. What Richie offers instead of a “take” on Japan is the sensitive eye and heart of a passionate, fair-minded man. His intimate profiles, whether of famous or unknown people, are equally rich in engrossing detail. By portraying Japanese as individuals, and by doing so with insight and often with sympathy, Richie gives the lie to conventional notions of uniformity. His unerring feel for what is genuine also fuels his writings on film, customs, cuisine, erotica and countless other facets of Japanese culture and life.

The foremost foreign expert on the cinema of Japan, his volumes on Ozu and Kurosawa are two of the finest books on directors ever written. He has also scripted and directed many films of his own, documentaries and short subjects. Most recently he wrote the script of the Inland Sea, based on his much-admired book of that title, an elegiac memoir of his journey into the heart of an island nation. Few authors on Japan approach Richie’s scope or intelligence, and none his prolific output. Not content to focus on film, he has created books of lasting value on topics as diverse as the city of Tokyo, zen, tattoos, ikebana, etiquette, and Buddhist temples. He has written novels and kyogen plays and, as a critic, newspaper columns that enjoy wide followings in Japan and overseas. For all of this, he shares the modesty of the people he lives among.

Early this spring at a table in Tokyo’s International Press Club, high above the noisy streets of Yurakucho, Richie talked at length with Janet Pocorobba.

Your memories of Japan extend over fifty years now. Does it feel like a long time?

I know just how Rip Van Winkle must have felt, because it went by just like that. If I had stayed in Lima, Ohio, I think my life would’ve been endless, like two thousand years. But here, everything is so interesting, every day has something new you can do, people you can meet. Everyday you wake up and think “What am I going to learn today?” And, of course, that’s what kept me here, and what made things go so fast. There’s always something to look forward to. Of course, I’ve been lucky. I’ve never had a proper job, so I’ve never had a nine to five situation at all.

You’ve always been writing?

Writing, or doing something like it. The closest I got to a normal job was at the Museum of Modern Art, where I was curator of film. They don’t have punch clocks there but they think you should saunter in about nine. Actually, I probably worked the most of anyone, mostly because I didn’t know what else to do in New York and because I just love to work. People ask nowadays, “My god, when are you going to retire?” and I say, “I don’t have anything to retire from!” So it’s very nice. I’m not stuck in any routine except those I make myself.

And what is that routine like these days?

I think you can only get freedom within bounds. I don’t know who said that — Sartre? . . . but I believe it. You set your own boundaries and then within those you find freedom. If somebody gives you freedom, it becomes a dreadful freedom and it becomes chaos and you don’t know what to do. If you can structure life to your satisfaction, with your own rules which you follow, then you’re free.

So this is my recipe for my freedom. Get up about 6:30, get the coffee and the Japan Times down me, take the shower and by 8:00 sit down to do four hours of work. It doesn’t matter what it is. And in order for that to not be too much of a routine, I have four of five things going at once, so I can choose the one that I want to do. One of them is my column, which comes out every week. Another one is whatever big work I’m working on, that would be under the title of creative, or what comes out of me or something. The other would be a sort of scholarly work. I’m doing a big book on film for Columbia now, which is straight up the cliff. That’s not a big favorite to choose in the morning but I’ve got to choose it, at least two mornings a week. And then, if I’m really a slack-off that day, I do my mail. Anyway, I’ve got to keep at the boards for four hours. Then at noon, I’m free. I usually make my own lunch, take a nap if I want, and then go out and make a living, because even though I’ve got forty-some books, none of them would ever keep me in breadcrust, let alone anything else. I write books they collect in libraries, you know, I don’t make money off them.

It’s staggering to hear that.

It’s staggering, but unless you’re Steven King or something, I don’t know who can eat on books. So then I go out and do things to make money. I work at International House, I teach school at Temple, I do movie reviews for the Herald Tribune in Paris, so I go to see the movies. I do subtitles for films — that brings in a lot of money sometimes. By 6:00 I’m all finished and then the social life starts, curtailed only in that since I get up at 6:30 in the morning, there can’t be too much of it. By 10:30 or so, I’m settled in at home with a good book, sound asleep at 11:00. So that’s it. Within those confines, every day is different, and I can always break it up.

Tell me about your new books.

I like them both. One is called Tokyo: A View of the City. It’s not a guidebook or history book. Perhaps a meditation on the city sounds a little too grand, but it’s a description of the city, what is feels like to be here, very deconstructive. As you go through the book you realize the shape of the city. The other took me the longest to write of any book I’ve ever written. My historical novel, it’s called The Memoirs of the Warrior Kumagai. Ten years of writing, rewriting, checking all the facts. This is no historical romance, it’s a real reconstruction.

Could you elaborate more on The Memoirs of the Warrior Kumagai? What is its significance in your view?

Kumagai? He is mainly remembered as the gruff warrior who in the Tale of the Heike killed the young and beautiful Atsumori, an event later celebrated in a poem, print and play. Except that he didn’t. And he is consequently disturbed when he hears the blind priests down the hall at the temple maintaining that he did as they chant the verses which became the Tale of the Heike. The memoir he is writing turns into a search of the past as he must incorporate his present investigations. And my whole book (except this central core) is based on fact. But with a structure like this, what is fact, what is fiction?

Most of your books are nonfiction. Do you have a preference for writing fiction or non-fiction?

There’s a book being written about me now, the locus of it being that almost all of my writing is autobiographical. A biography disguised as a travel book, like The Inland Sea, or books which are purportedly about other people, but if you notice that big hole in the middle…

Like in Public People, Private People…

I tend to be a self-revelatory kind of writer. I think of reason I do it — I’m actually pretty cagey and not too good at revealing — but what I like to do is have a still center in the middle of whatever I’m doing, and that’s me. I think everybody feels that, but very few people go to the extent of actually including it, which is what I do. This biography about is called The Great Mirror. That’s not me, it’s Japan. The idea is that you look at yourself in Japan as if in a mirror. We all do that. If you don’t like what you see, you go home, but if you do, then you can spruce yourself up a little bit and maybe turn into a better person. It’s a very sound idea.

Living in another country has brought out from me books which are structured upon what I have decided, or discovered, my personality to be. Certainly this is true with Kumagai. When my wife saw the first draft ten years ago, she said, “Donald, this isn’t history, this is you.” She was right, so the next ten years was spent getting rid of that. It’s still me, but a more complicated subtle view of me. The book on Tokyo certainly has me as the center. One might say that my work is ego-bound, but I can say it’s not, because the eyes are always at the service of something else. But it certainly is self-bound.

Do you still feel like a foreigner in Japan?

Yes. I think if I didn’t feel like a foreigner, I wouldn’t be here. And if I were Japanese, I wouldn’t stay here ten minutes. I like being a foreigner. It’s so rewarding not to have to belong to things, not being allowed to belong to things. It’s really free. When I was taking things for granted back in Ohio, it never occurred to me that I could lead a life in which I set my own obligations and decide how I want to comport myself. Because if you never leave your native culture, you’re forever bound by it, without ever realizing it. If you ask a person in Ohio or Japan about their own culture, it’s like asking a fish about water. What can they say? When you come over here, or anyplace, and you get your eyes opened, you can never get them shut again.

Did you come here during the War or just after?

After, in January 1947. During the war, I certainly didn’t want to be in the army , because at that point in the war — ’42, ’43 — everyone, like boys from Ohio, went into the infantry and got killed. So with my father’s help I got into the Foreign Maritime Service, the Merchant Marine, which was dangerous but not dramatically so. We followed the armies in, so I was at places like Salerno, but I was always two or three days later, bringing in the toilet paper and the chocolate. When the war was over, I didn’t fancy going back to northwestern Ohio at all. I had heard that the Foreign Service was taking people to occupied territories. Germany, Japan. I opted for Germany, because I wanted to see more of Europe, and they, in their wisdom, sent me here.

How ironic. You hadn’t even opted for Japan.

I knew nothing about it. I’d been in Europe and I liked the idea of finding out more about it, but they sent me here. But I wasn’t here a week before I knew that I was onto something absolutely extraordinary.

Exactly what was that? Do you recall particular impressions?

Imagine the freedom of looking at something and not knowing if it was edible or not. My first view of wagashi, Japanese sweets. Or not knowing if it were a shoe or a tool. My first view of a geta. And imagine seeing things you know (A saw, for example) that worked backwards. Everything was fresh, lying there, ready to be picked up and explored. All except where I initially worked. I came over attached to a very uninteresting part of the Occupation. It was part of the legal section, foreign acquisitions. I came over here as a typist, because the one thing I learned in Lima Central High was how to type. I was our county champion typist, and while I have this great talent, I’m not particularly fond of it , so I didn’t want to remain a typist. Once I was here and found that I was to be put to work day after day doing columns of numbers, I started moving around and the Occupation was so fluid at that point that one could do this. I did a human interest article that happened to be at a time when they had just taken down the signs that said “No Fraternizing with the Indigenous Personnel” and they were deciding to change their attitude toward the defeated people they were occupying, and so now we were nice to them. My human interest article about a man who lived under a bridge occurred at just that point, and it appealed to the authorities. I soon found that I was a features editor at Stars and Stripes, as well as a film critic. So from then on I was able to write about anything I wanted to. I turned Japanese culture upside down like a cornucopia and out came all sorts of things for me to learn about, to write about and to instruct others in. this continued until I left in 1949, when I had a chance to go back to school at Columbia. But I knew was going to come back here. In 1953 I graduated and came right back, and stayed here fifteen years, until I went to New York to the museum. I was at MoMA until life in New York just got too awful. I missed Japan very, very much, especially Tokyo, so I came back in 1975.

So you were actually in New York for seven years?

Yeah, but I cheated. I would only stay there for three seasons and come back here every summer.

What do you think of New York, as compared to Tokyo?

I’ve seen New York change. I know the city quite well. During the war, I was there as a merchant seaman, and I found it was the most exciting place in the world, but by the time I got to MoMA, New York was changing swiftly and becoming the dangerous city that we all remember. And the coldness of New York began about then, when people were afraid to live there. So I had a wonderful time at the museum but I didn’t really have a good time in New York. I still think Tokyo is the warmer city, maybe simply because I’m a foreigner.

Japanese have many times told me that they consider Tokyo to be a very cold city, compared to, say, Osaka. Of course, the coldest city is Kyoto. It’s like Boston unless you are well-connected there. This is true, not particularly of foreigners, but of the Japanese themselves. Unless they’re born there, they simply don’t want to live in Kyoto. So if Kyoto is zero degrees, we get up to a sort of livable heat in Osaka, then someplace in between is frigid Tokyo. But as a foreigner, one is immune to temperatures. There’s no way of telling how the Japanese are feeling about anyplace because they regard themselves as so completely different from us. We’re always either a welcome or not-welcome exception to what is going on around us.

You’ve seen so many changes in Japan. Does anything in particular stand out in your mind that is so different from what it once was?

Physically, when I first came here, we used to walk up to the Wako building [in Ginza] from work and stand on the corner because it was the best place in town to view Mt. Fuji. And spiritually there was what John Dower calls the “culture of defeat.” The Japanese were extremely poor after the war and they were going to starve if the American airlift hadn’t saved them. They were quite aware of this and one of the things that they could do to make it more livable, was to make this “culture of defeat,” which had many litanies, one of which was, “Well, I’m just glad Japan lost the war, I’m just happy it lost.” And this is rationalized, of course, by the fact that if Japan had won the war, it would’ve been like Germany having won. This attitude was a way in which to live.

We, the conquerors, the Occupiers, were nonetheless quite aware of all this, and those of us who did not like the slapdash way in which the military did things (I don’t know about the American military now) formed a smaller core inside the Occupation, doing our best to discover Japan. I was working at Stars and Stripes, so I was studying very hard, and was learning a lot about Japan, which was a culture which had (one you take away the war-time military stuff away — and it was all taken away — and you get down to something more basic, which the military had indeed covered) something left over from its earlier days. I remember I was living by the Spanish Embassy then, and they were a repairing a wall near there, and there was a very large beech tree that was in the way, so they made a hole in the wall so that the tree could go through.

Things like this happened all the time. It’s unimaginable now. They’ve concrete-covered the whole island, they’ve ruined the coastline and dammed all the rivers. So what I really find changed is the Japanese attitude toward their surrounding. Now, it’s as though it’s been decided that there is nothing greater than monetary profit and everything will be done to achieve this, no matter what sacrifice you have to make. So, without thinking, all these wonderful attitudes toward human beings, toward nature, toward other life, has been pretty well eradicated.

To keep up with the West . . . ?

Well, originally it was that, but now it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. Once you get started, greed takes over and you want more and more. This unholy trinity of the construction companies, the government and the yakuza, it’s redone the country in the most shoddy fashion. England has the same problem, but at least managed to keep an attitude which the Japanese — maybe because no one was defending — lost. I mind that still. People ask me if I have any regrets. Well, that’s the only regret I have. Japan was the most beautiful country I’d ever seen, and I’d seen a lot during the war. It was heaven. When I visited the Inland Sea, it was astonishing.

When was your first visit to the Inland Sea?

The late 1950s.

So that book was written over a period of time.

Right. When they made the film of it twenty years later, they couldn’t use any of the original places. None of the island are the ones I wrote about because they’d all been concreted over at this point, or they’d launched the big bridge. So it’s this attitude toward life which struck me as being so much better than what I had come from, and that I’ve had to watch erode. I’m still looking for pockets, which I find, in Ueno, for example, where I live. A lot of it would seem to survive. We’re in next week for an absolutely orgy of cherry blossom viewing. But this institutionalized nature and that’s quite different. This is nature tamed. It was the respect for nature itself that was so impressive, and that I find increasingly rare now.

Anyway, those are among the differences, and I have to balance this by saying that when I first came here the average person lived to about 35 or 40 years old before s/he died, they had awful kids with club feet and cleft palates, blind. Now Japan has the longest life of any nation on earth, the incidence of child trauma, early death has gone way down, more things can be done now to improve life for more and more people. So in a trade-off. I don’t have any kids to worry about, but I do care about the aesthetics of things and so I do miss this attitude, and when I don’t see it in people anymore, I miss that as well. Those are among the changes.

Was there a time when you realized you didn’t want to go back to the U.S.?

Speaking in emotional terms, without any rational reason, how did I feel? I knew it the day I left here in 1949. I’d been toying with the idea of my career while I was here in 1947, ’48, ’49 — what to do. I remember waiting in Yokohama for the boat to take me — we went by boat then — back to America, and thinking, “What am I doing? I don’t want to leave. My life is here!” And I carried that feeling all the way through school. It really changed me.

I would get boxes from friends in Japan that I would open up and the smell, which I associated with Japan, would come out of the newly-opened box and I’d burst into tears. So obviously some great emotional investment had been made. I knew that something had happened to me, although I hadn’t made any decisions, something very important. Some research is being done in that area now — it’s much-neglected — of how Japan in that period (the 1950s) affected people emotionally.

Do you think you would have become a writer if you’d gone back to Ohio?

Yes, I absolutely would. I know this for a fact because that’s the first thing I started to do when I was little. I wrote my first book when I was ten. Not much of a book, it had maybe two pages, but nonetheless, I made the attempt. I discovered the wonder of words when I was a child, and I discovered going to the school library that words empowered me, that I could read about certain things and I could visualize, make them real to me. And that empowerment gave me first, a way to get out of Ohio for an afternoon, and second, later on, the realization that if this writer’s words can move me, I can do the same thing and move somebody else.

What’s your feeling on revision? Are you obsessive about it?

I didn’t used to be. I learned to be, and I learned to love it. Now I like rewriting more than writing. For me, writing is drudgery and labor: to put the bucket down into the well and try to find out what’s squirming around the inside and throw it on the typewriter and be dissatisfied with whatever you’ve done with it. I let it sit, like in an oven, for a day or two. If I do it too much longer, I lose whatever impetus or interest I had. I want to keep up the interest, but at the same time to approach it fresh. Twenty-four hours will do wonders. I see all sorts of things. What I can move around, what word to change. I like that kind of work. And I don’t let anything go out of my hands until it’s just about as good as I can do it. It depends on the difficulty. To spend ten years on a book argues for a lot of things.

On the other hand, the way that I do my book review columns, which are perfectly decently written, is I read the book and take notes. Then I will sit down with the notes — I already have in mind the shape of whatever the review’s going to be like — and I simply write it in one hour, never more than that. Then I spend the next fifteen minutes going over it again, changing things very lightly, and I send it out. But that is only because I’m there dealing with a shallow professional layer of myself, and I know all the rules now and what my voice is and I don’t have to experiment with what I mean, and I know what my reader is like, all too well, and my editors. So given all these boundary lines, I find my own freedom to do these little columns every week.

However, with other writings, it’s entirely different, once I don’t have rules. For example, the things I’m writing now — the new Columbia University book on Japanese film, and also a new novel which has come knocking at the door unannounced. It just appeared, so incomplete, without any sort of introduction. It would have been a mistake to turn it away. I’ve done that before and I’ve paid for it. So I headed in and started tooling around with the home computer and it took the most interesting shape. It dictates itself for an hour every morning, I don’t have any reins on it, I just let it trot where it wants. Occasionally I can say, “Too dumb,” and nudge it over, and then the following morning I’ll go over it, and since I know more than it does, I’m able to block it into some sort of shape.

It’s a very strange novel. It picked its own title: Other Islands. It’s not about Japan. It’s about time and death and age; I think it’s about my long-forgotten parents. It’s the story of a man who goes to an island, very classical, he’s on a boat and he doesn’t know why he’s going, and on the island he meets people. The way I think it’s going now, is that these people — a very nice girl who works in the hotel there, a guy on the docks — these are his parents before they had him, before they married. He’s very attracted — he’s an old man now — to these young people, and I think what the novel wants me to do is to procreate myself. I don’t know. I’ll have to wait and find . . .

You don’t know the ending, you’re just going with it?

Right. I’ve never done that before. I’m usually an obsessive, picture-straightening kind of person, so to trust myself with something that I think is important like this is unparalleled. So in the morning I’m torn between doing something I know I can do very well, which is write a history book, or put on my hip boots instead and go out and wade in the swamp. I try to do it every other morning to keep some sort of balance.

Do you tend to write all in a burst, or make little notes along the way, or get mad flashes of inspiration?

Again, it depends on the type of writing. If you’re doing expository writing, like history or something, you really to stop every two minutes for a footnote anyway, and so it’s more like a mosaic. You watch its progress and you gauge it so that your critical faculty and your creative faculty are working simultaneously. However, in the case of a novel, the way I function is to get something down. I get something down in order to have something to correct, because it’s the most difficult thing in the world to even think about something when you don’t have anything in front of you. So I get it all out, or as much as will come out at that point.

And keep the editor at bay at the moment? That’s hard to separate the two.

Being creative, no matter how romantic it sounds, is never really very much fun. It’s always so easy to call in the critic because he appears to be beneficial when he stops the flow of things. “Oh, that word’s wrong,” or “You don’t need a comma there,” but every time you do that, you lose something of the alpha wave, something of the push, and even if the push is in the wrong direction, at least it’s a push . . .

Once you’ve decided who’s going to do the telling, then you’ve decided the voice and once you’ve decided the voice, you’re in. It comes natural after that. That was part of my trouble with Kumagai. The reason it took me ten years was that I had it in the third person and it lacked everything. It was patronizing and stodgy. I wrote the whole thing and then it hit me that it should be in the first person and then instantly everything changed.

What about advice to write about what you know, as opposed to pure invention?

It depends on how well you know what you don’t know, if you’re going to write about something like Ursula LeGuin, who’s obviously never been to any of the places she writes about because they don’t exist. But her imagination is something she knows and that’s something real so she can write about it. I think that advice is probably for beginning students, for people who can’t really be trusted to know their interior limitations, so therefore, write about their life. You’ve got to get all the details right. I think that’s what they mean, but on the other hand you can’t write without imagination. Kumagai — I’ve got all the physical facts but that’s just the bones. It’s what I do with the muscles, the skin. It’s my imagination. So you re-live what you’re writing about.

Do you read a lot of American fiction?

Right now, not so much. There’s a lot of Americans I like. I like John Cheever, I’m very fond of Raymond Carver. I’m fond of southern writers like Carson McCullers, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor.

Is there an equivalent to Raymond Carver here?

I would think so. There are a number of minimalist writers here. Whether they’re as skilful as Carver I have no way of knowing. What he’s writing is really cut down. He would start with a big story and just chop thing up — and plastered the whole time, too. Whether we have any Japanese writers that approach his modesty I don’t know. His is a true modesty. We have here abjection, which is different from modesty, and we have show-off modesty, which is again different. I know that in translation he’s very popular here, everything’s been translated and sold and sold and sold. He treats of a social strata that doesn’t have any voice here, which is the upper proletariat, the rural proletariat, right? And that has no one speaking for it here that I know of.

What about Japanese writers?

Well I certainly admire the older generation. Tanizaki, extremely, Kawabata very much. I like the freedom of form that literature very often takes here, where it’s not subjected to the Augustan cadence of Samuel Johnson for example, but something much more natural. Look at how a Kawabata novel flows, and yet it really is not impoverished, it has its parallels, it has everything that makes a novel go. Very often it doesn’t end, it just stops. But this kind of attitude toward literature, the idea you can do an essay, a zuihitsu, which is just a following of the brush. This kind of freedom that I see in Japanese writers is very appealing to me.

I don’t like it so much when a Japanese writer will then ape Western form. Mishima, for example, who lacks entirely the spontaneity I admire. I’ve been commissioned to do a book on Mishima now, and I don’t know, I’ll think about it. I don’t want to do anything that pretends to be other than it is. I knew him quite well, he was a friend of mine, so this would be my reason for doing it. On the other hand, I’m in disagreement with half of his work, so that doesn’t seem very fair, does it?

Particularly I admire the Japanese confessional mode. My favorite Japanese writer is Nagai Kafu, who wrote about Tokyo, of course. Ed Seidensticker has the most wonderful book on Kafu called Kafu, the Scribbler. I’m consumed with envy when I read that book. I’d love to do one like that. So I guess I admire Kafu best. Certainly I enjoy reading him the most.

Besides yourself, who among Westerners are doing the best job nowadays of writing article or books in English about Japan?

Well, I’ve already mentioned Ed. I would add John Dower, Ian Buruma, William LaFleur, Karel van Wolferen. There are many other as well doing excellent work in Japan. One of the similarities is that they are not theorists, they do not write Nihonjinron. They are draughtsmen who draw Japan precisely as it is, not as it should be, nor even as they would have it.

Do you have any favorite Japanese woman writers?

Most of them. I find that women write better than men, usually.

In Japan?

In the world. All of my favorite writers are women. Flannery O’Connor, Lady Murasaki, Sei Shonagon—I read all the anonymous court ladies and get a tremendous insight through their candor and lack of bullshit. And then contemporary writers, there are a good many that I like, although I don’t like Banana Yoshimoto very much, but that’s because she’s busy trying to be a boy and if she were to bring what she has naturally, it would be a different question. Amy Yamada I like a lot, and Yukio Tsushima, Dazai’s daughter, who’s a marvellous writer. And then there’s Michiko Yamamoto, she wrote a book called Betty-San. I like women writers for their perceptions. They’re in a non-privileged position, just as a foreigner is. For a male foreigner here, it’s almost an emasculating thing. It takes care of your macho when you suddenly realize what it’s like to live in a minority—a fairly powerless one—and there is a majority that attempts to dictate what it is you’re doing. So you can appreciate the way in which women through the ages have lived and at the same time you can appreciate the honesty and candor with which the greatest—Colette, for example—have written about their condition and you really trust that. I trust Simone de Beauvoir more than I trust Sartre, and Colette more than Scott Fitzgerald. These guys are trying to prove something beyond what they’re writing.

When asked to name your favorite Japanese authors you listed Tanizaki, Kawabata, Kafu. But a few moments later you said that all your favorite writers were women. Is this one of those “I contain multitudes” contradictions we all make?

Or “Do I contradict myself? Very well, I contradict myself.” I suppose because I am a man I thought of men first but, really, I read more women and I like them better. Except for a few men. I find James Boswell irresistible.

You’ve travelled extensively over the years. What is one of your favorite places in Asia?

Bhutan. I’ve only been there once. I can never go again. At 8,000 feet it gave me a heart attack. Bhutan is really an eighteenth-century country. The airport is a fieldstone hut with a turf roof and your transportation is two yaks. They have roads, a couple of cars, too, but the architecture is still thirteenth century, the people don’t know anything except the native garb. And yet, the priests send each other sutras on e-mail and everybody speaks English as that’s the second language. It’s the most modern and ancient civilization at the same time. Absolutely fascinating. I was there fore ten days and I didn’t even notice I wasn’t breathing. I think that’s the most exciting and interesting place I’ve ever been, but for a more comfortable time I’m very fond of Bangkok, and of the Thais, as indeed who isn’t? Places I’m not too fond of? Singapore. I shan’t go there again . . . city-states like Shanghai, Hong Kong, Jakarta . . .

What about in Japan? Tokyo of course . . .

Yes, Tokyo, and Tokyo’s what all of Japan is going to be someday anyway. I’m very fond of Satsuma, which is very far south in Kyushu, on the Satsuma peninsula. One of those places that the Tokugawa cookie-cutter missed. Chiba and Ibaraki too. The feudal power didn’t extend that far so you didn’t get punished for being yourself as you did in Sendai or Edo. I like Satsuma people a lot. They’re like Elizabethans—boisterous and opinionated, hot-headed, much given to fisticuffs. At the same time they’re very human and very reasonable. They’re extremely open.

But Tokyo is home.

Tokyo is home. I know Tokyo better than any other city on earth, so why don’t I feel that way about Tokyo? Well, it has to do with the fact that I live here. So what I’ve done is I’ve used up my tourist self in these other places.

Do you have a favorite area in Tokyo?

Where I live, Shitamachi. I’ve been living there off and on for a good many years. A lot of it is nostalgia, because it’s old Tokyo. It’s the last place in Tokyo to get the latest whatever it is, and even so, the latest doesn’t quite cover up the old as it does in other places. That’s the main reason I like it. The other reason is that people are still recognizably people there, they’re not like a new breed. When I go to Shibuya, even if I were to talk to some of the people there, I don’t think I could think of anything to say that would interest them. I feel the young are taken up with whatever shinhatsubai [new product] is in that week. They’re interminably self-conscious, and their own relations with each other are such that I can’t imagine then being able to learn very much. This is certainly true of commercial centers such as Omotesando and Aoyama. Not true in Ueno. There, you still talk to people, and get answers.

I’m an old codger to be saying this, but it does seem to me that a lot of the old virtues that I knew—the spontaneity of the Japanese, all these things that we don’t really think about, the dedication to this and that, their craftsmanship, the basic honesty with themselves, with the world— are still there. The country has changed so elaborately that I don’t find it existing to the extent that I used to in most places. It’s still very much here in Shitamachi, so, I like living next to what I consider Japanese nature, or being a part of it.

Of the traditional Japanese arts, which do you prefer?

The kyogen.

That’s right. You’ve written kyogen plays.

Yes. I also like the Noh. Whenever I have a chance—that is, a freebie, because it’s so expensive—I go to the Noh. I like Noh very much. Kabuki, I’ve always been of two minds about. I feel that I sort of know it. In 1961, when the Grand Kabuki went over [to New York], they took me along as interpreter/translator. I gave the simultaneous translation for the repertoire, so I got to know the repertoire and the actors of that period very well indeed. And little by little, the charms of Kabuki wore thin, as far as I was concerned. It’s such a compromised drama. You can probably tell from my writing that I’m nothing if not an elitist. So the idea of this grab-bag that constitutes the Kabuki, plus some highly questionable moral values, by which I mean, plays that turn upon the wisdom and virtue of sacrificing your own son so that the lord’s is not killed. That sort of thing makes me sick. What Kabuki is about, is bad faith most of the time. Of course, I realize this is absolutely not the way to approach an art. But nonetheless, I’ve decided I don’t like it. So Kabuki is not high on my list of things Japanese that I pay much attention to. Film, however, is my passport, so I keep up on that.

But I specialize in people, really, and they happy to be Japanese since I happen to be here. I hold the opinion, even now, that Japan is madly pluralistic, just as much as America is. That we have just as many different points of view, really. The thing is, it’s hard to see without help. It takes an amount of attention that foreigners don’t want to give. So they settle for the ant colony and everybody looking alike, acting alike, which is not true.

You say that Japan is as “madly pluralistic,” as America is. Could you elaborate?

I should also add that everywhere is madly pluralistic, including Russia and China. People are just too various for states to impose mindsets on everyone. The only way to make people single-minded is to punish them. This is what the Tokugawa regime did, frightened people for centuries. But under this seeming order, the old disorder roiled. It still does and people are much less afraid of authority than they once were. There is some lip service to Japan the monolith but this is now mainly habit. If you want to see pluralism read Kenji Nakagami, see the films of Shohei Imamura.

Are there Japanese filmmakers working today—either in features or documentaries—whose movies are worth watching? Could you briefly describe the current state of Japanese cinema?

Yes, many. Imamura is still working, for example, and there are lots of new, younger filmmakers. Mitsuo Yanagimachi for example—he made Fire Festival. Or more recently, Makoto Shinazaki, who made Okaeri, or Hirokazu Koreeda who made Maboroshi and the splendid new After Life.

What view do you take of the phenomenon of Japanese animated films? Do you watch any? Do you like any? How does the success of animation shed light on the society or culture?

Japanese anime could be seen as the quintessential Japanese product. Most of the culture here is in the presentational mode (all the drama has someone to tell you the story, the gardens are created by hand and then called natural, flowers are cut and arranged and then named ikebana) and not in the representational (realism). Animated cartoons are pure presentation, nothing actual or real is allowed near them. They are purely expressionist—reality is thus always alternate. Alternative reality is notoriously flimsy, however. Perhaps that is the reason anime are so fast, and so violent, they have to make themselves apprehendable through splash alone.

As for the impact on society, anime, like the TV games that spawned them, gives the impression of control. One could, you will remember, starve the tamagotchi to death if one so chose. These gadgets give the power-deprived young the impression that they are in the driver’s seat. So do manga. So do anime—the ultimate presentational (every frame hand-digitaled) narrative.

You were talking earlier about changes in Japan. What’s really in danger here traditionally?

We live in a Heraclitean world, and things change. If they seem to change more slowly here it’s because Japan has a sort of taxidermal process going on where even if something’s no longer alive, it’s still propped up, like the Kabuki, the Noh, a lot of the so-called traditional arts. These are no longer viable as far as society goes, and yet, they’re kept. Now we don’t have any Victor Herbert operettas still being done, nor does any other culture, but Japan alone keeps these stuffed replicas up there, and then passes them off as traditional culture, which it is, but it isn’t alive anymore. This often gives the impression that we’re in the land where time stood still, but this is not true.

We’ve already reached the point where you almost cannot afford a kimono now because the unit price is so high, where tatami is going out so swiftly that soon you won’t be able to get it anymore. They’ll turn to plastic and then they’ll stop making it. When I first came here, houses were all tatami with one Western room, then it was all Western with one tatami room, and now the newer apartments, like the place where I live, have no tatami. Another thing, the young now complain that chopsticks are too difficult, that knives and forks are much better. And, of course, all the food that goes with a knife and fork. Recently the Japanese breakfast has gone way down. In the city people don’t want to make rice or miso soup. It’s toast and coffee, milk. Convenience always wins in the progress of civilization.

We’re changing, the whole world’s changing, and it’s accelerating because communications are so much more efficient. The Japanese family, which we didn’t think was going to evaporate, is now coming apart severely. Some of the old forms are sort of patched together and till manage to chug along, like the government. Really, there is no government. This country’s a chicken without a head. There’s nobody who runs this country. It’s run by oligarchies, but the oligarchies are all abandoned now. It’s just like the companies that are falling apart. No new bonuses this year—what’s this going to do?

Obviously, things are coming apart. The escalator to the top in a company has long since stopped. You’re lucky if you get to the top by the stairway. So structurally, all of these things which were something from the Jurassic Period anyway are finally coming unstuck. These are very real changes and these in turn will—domino effect—change everything in this country. We’ve seen it coming. It will become much, much more grand. I have no idea what the country’s going to become. At first, it’s going to have an unfortunate period where it’s going to turn into the Philippines, that is, sort of a toothless creature made of two cultures. But given Japanese pragmatism and energy, I daresay, something will occur to fill the vacuum. The mindset that we’ve been living with for the past 50 years is coming to very rapid and spectacular conclusion. So I’ll see the whole show, including the pyrotechnic finale.

You say you are no theorist, but do you have any way to account for what is occurring? Any lessons to be learned? How does one understand Japan’s handling of its own identity?

There used to be two schools of thought here. One is that in Japan the surface changed but the core held. There are a lot of people who propagated this, Reischauer for example, but this is no longer tenable. The core is not holding and indeed no core ever holds any place in history. Did the Aztec core hold? No. The Incas? No. So the Japanese are going to vanish as we know them, but 100 years from now, they will not be known as anything other than what they’ve become, except if you an antiquarian and read a book by me, for example. Change marches on.

But I imagine that Japan would keep its penchant for identity through the past. America identifies itself entirely in terms of the future. It’s in a bind now because no place to go, you don’t have the great west to conquer, forefronts of modern medical science of anything like this to live on. So what’s America going to do? I don’t know. What’s Japan going to do? It notoriously has predicated itself on the past, so much so that the Emperor was a god and we all descended from the sun and we’re 2008 years old. Well, this has all been brushed aside, but predicating on the past is still very much in evidence. I would imagine this would continue even more. Japan will become quite reactionary, I imagine, as more and more the threat of the present, rather than the future, becomes more and more real. I’m sort of looking forward to it because it’ll be so different. And so I can lament it and regret it as much as I like, but at the same time, I feel a very real excitement in being able to see it.

One of the great things about being an expatriate is that you have a grand sense for whatever’s happening. You’re up on the mountain, and back there where you came from they don’t know who you are and they don’t care, and you don’t have to care about them and they’re a funny tribe anyways. And down here is the Promised Land and you can’t go into it, you’re not allowed. So what you can do is compare, and the act of comparison is the beginning of comprehension. In the coming turmoil it’ll be very interesting to have such as good seat.

If you could return one thing to Japan, what would it be?

I’d move back the clock. I would like to return the attitude Japan had toward nature, by which I mean human nature, by which I mean the natural world. The way in which the Japanese related to their surroundings. I would like that to return. It’s impossible because what made them change was an economic imperative. We are an island nation the size of California, containing half the population of America in numbers. The most overcrowded place on earth. What do you expect them to do? They’ve all got to live here, and they don’t have an empire anymore, and they themselves don’t want to have a diaspora. They don’t want to live abroad. It’s getting worse and worse, despite the fact that there’s supposed to be a zero percent birth rate, as all these old codgers refuse to die. I can understand so well how it became the way it is now, but nonetheless if I had my wishes . . .

If you were going to give some kind of advice to foreigners here on how to live a happy or successful life here, what would be important for that?

Don’t try to join. Realize that we are on this planet merely in order to observe and understand. That the joys of comprehension are the only true joys there are. How’s that?

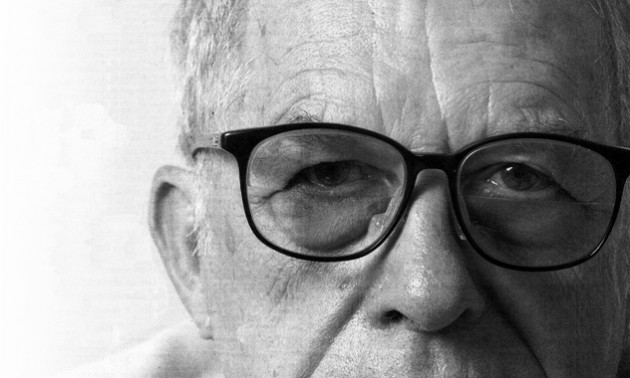

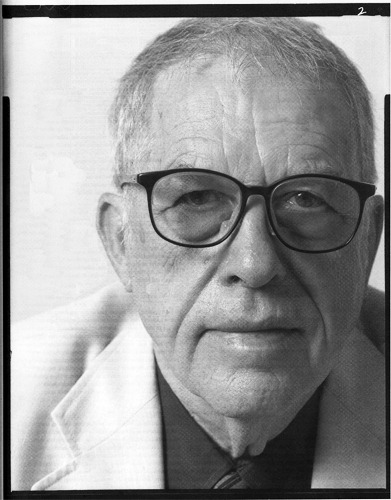

Photograph by Everett Brown