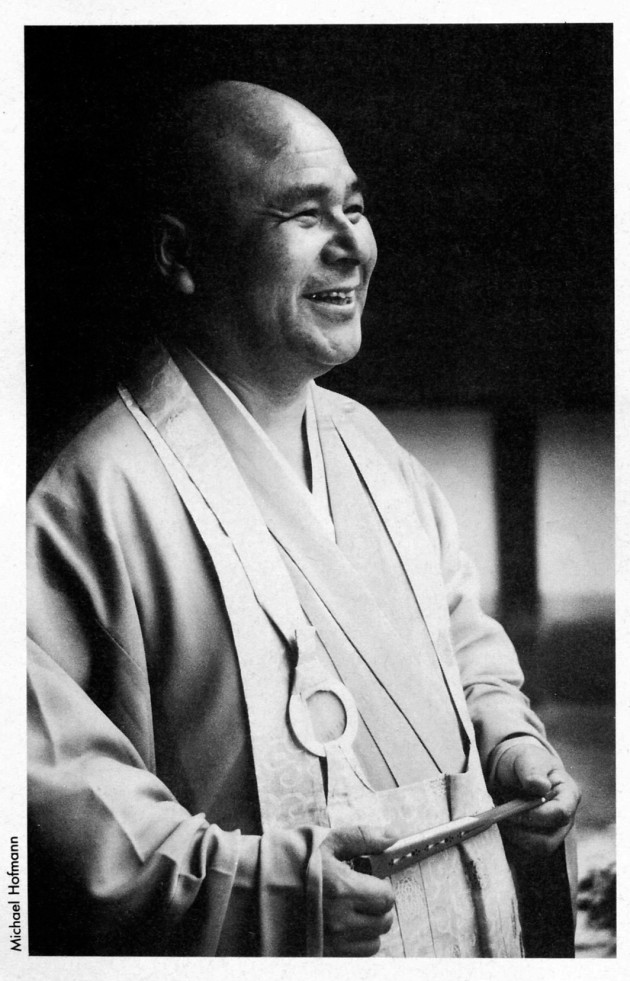

[A]s the Zen master of Tofukuji Monastery, one of Kyoto’s “Five Great Temples” Keido Fukushima-roshi at 56 is one of the youngest men in Japan to fill such a position. A frequent visitor to the U.S., Fukushima-roshi expresses concern about the development of Zen in the West.

On a warm afternoon last spring, with the cherry-blossoms dotting the eastern hills, Fukushima-roshi talked with Pico Iyer, a writer forTime Magazine, and Michael Hofmann, a long-time friend from California, who has spent the last 17 years pursuing Zen sumi-e painting in Kyoto. Speaking in both Japanese and English, and using as interpreter disciple Alex Vesey, who has spent five years training at Tofukuji, Fukushima-roshi delivered a stern warning about the state of Zen in America, and talked at length about Buddhism’s place in a secular and materialistic Japan.

Can you tell us a little about your impressions of Zen in America during your most recent trip?

I was very worried. While we were there, we heard about a man, the head of a Zen Center, who says that he has trained ten or twelve Zen masters. He claims to have created these Zen masters in just 7 years! And that’s impossible! The style of training in American Zen centers has a certain simplified, “easy” aspect to it.

If you think you would like to become a Zen master, the minimum time for a Japanese man would be at least 10 years. And after you leave the monastery, you have a training in which you become a resident priest of a small temple, and this too is a process that will take at least 10 years. It’s aimed at furthering your enlightenment process after you leave the monastery. For a Japanese monk, therefore, the minimum amount of time needed to become a Zen master would be 20 years. For an American monk, it would take at least 25 to 30 years. It is a long path.

In America, however, Zen masters are made with a lot more facility, and Zen masters who have not completed a real training will go on to create more Zen masters who are even less qualified. This will ultimately have the very bad result that Americans will not be able to understand what real Zen is. A whole revision of Zen in America is needed.

Some centers are doing a pretty good job, so we can see that it is possible for Americans to master Zen training. There is always a possibility for Americans to attain satori. But in America, people ask the question, “What is the fastest way to get satori?” Japanese lay people don’t think in terms of gaining satori or becoming a Zen master. But Americans have a lot of pride; they love to take on challenges. So everyone immediately starts to think, “I want enlightenment.” Americans have to settle down and think more about these things. I think it’s an important time for proper leadership and a revision of Zen in America. I worry a great deal about what will happen to Zen in America.

Are there any particular obstacles that would make it especially difficult for Americans to come to terms with Zen?

Americans are more intellectual in nature. But in koan studies, one must proceed with great discretion, with care. Some people in America, without having even completed the full training, write books on koan study that include not only the questions, but the answers! Yet koan study is not just like a puzzle that you can solve. So books that include answers are really only a hindrance to those who wish to study. Among my disciples, these kinds of books are regarded almost as dirty books. Americans who do not take care on this point will end up causing lots of problems.

Is it also a problem that foreigners tend to read too much about Zen?

No matter how much you study, that is good! But if you go through Zen as an “intellectual investigation,” that interferes with your training, because it’s all in your head. Still, the things you studied can be of use later in explaining Zen to other people.

What is the most difficult challenge for any student of Zen, Japanese or American?

The main obstacle to pursuing Zen is that you tend to approach it with your head. One should not talk about the koan; one should become the koan. Rather than just understanding the koan, it’s better to experience it. Even for Japanese monks, though, this is a difficult problem. The experience of satori is one in which you transcend dualities. So, ideally, you should transcend dualities, even though you have to live in a world that is very dualistic. In the beginning, the training emphasizes transcendence of dualities. However, our own intellect comes from a dualistic basis. So you have to forget your own intellect.

Zen Buddhism does not condemn, or look down upon, the intellect per se; that’s why there are many written records in the Zen tradition. Yet, understanding Zen through the intellect is a mistake. That is why in the first three years of my own training, my master, Shibayama-roshi, kept on telling me for a whole year, “Be an idiot! Be a fool!” This was very good advice.

Today more and more people in the West tend to associate Japan mostly with its technological and economic aspects. Certainly the country seems to be changing at a record-breaking pace. Do you think that Zen has to change to keep up with it?

Zen itself — the experience of Zen — does not need to change. But in order to speak to modern people, Zen must change its expression. This has been a factor throughout all periods in history. Religion tries to teach people, here and now, how they should live.

For people in this day and age, for example, the question of what happens when you die must be explained fully and clearly. One hundred years ago, say, people would have thought that Buddhism was not a religion if it explained things in this way. Until the point of death, one must live as fully as one can.

The thing that Zen wants to emphasize is I as I am, here and now, and the thing that Zen wants to teach you is how to live in the here and now. However, in more ancient times, Buddhism taught that if you did bad things, you’d go to hell, and if you did good, you’d go to the Pure Land, or whatever. But if you tried to explain things in those terms today, modern people would just not believe it. They’d ask you in return, “You show me where hell is!” You would have to explain to them that going to paradise or to hell is not something that happens after your death; it’s something that happens right now. Either you’re living in paradise, now, or in a hellish fashion.

For the Jodo, or Pure Land, Sect of Buddhism, for example, there is a belief that the Pure Land exists in the West. However, if you were to explain to an elementary school child that the Pure Land exists in the West, he wouldn’t be able to understand it.

Let me tell you a story. One day, an old man was trying to explain to his grandchild about these things, and he said, “In the West — that’s where the Pure Land is!” And the child pointed out that if you go west and west, you go right around the world, and come back round to where you are!

Yet the Zen student cannot afford to turn his back on the world.

No. The ultimate purpose of Zen is not in the getting away from the world, but in the coming back. So while it is understood that you may go into the mountains by yourself to train, this is only one part of the training. However, if you do not go into a training center, like a monastery, or the mountains, to create that fundamental understanding, it’s very difficult to complete your training outside that kind of seclusion. But that is only half of the job. And so, after experiencing things in the monastery, when you go back out into the world and carry on your training in that situation, that’s when Zen really becomes a religion.

No matter what religion you’re talking about, in the end one must come back into a world of love and compassion. Zen Buddhism is not just a matter of gaining enlightenment; it’s a matter of helping other people.

Do you find that interest in Zen is declining as modern Japan keeps changing?

Not at all. In fact, the number of people who attend our monthly zazen session and lecture has increased greatly, as it also has at my twice-monthly lectures at the Asahi Shimbun Cultural Center in Osaka. Indeed, there are many companies now that wish their employees to undergo a little Zen training, or at least to have some experience of it. In the spring, new company employees are often shipped off to a Zen temple for a couple of days to undergo a little zazen.

But does being in a temple for such a short time really do any good?

That’s a good point. You’re not going to be able to get any understanding of satori in such a short time. But in a Zen monastery, there’s a very simple, traditional way of life, while in the outside world — especially somewhere like modern Japan — there’s a very extravagant way of living. So by coming into the temple for even a short time, people can be taught that there’s a simple way of living, too. Also, in a monastery, it’s a very structured life, a life based on rules. Most importantly, for the modern man who’s so wrapped up in progressing, sitting in a temple for even one night, and sitting zazen for even one period, forces him to stop — and this is a rather big experience for most people. So they see a different way of living, a certain calmness and quietude that doesn’t exist in ordinary life.

Most young Japanese people don’t want to go to a temple these days, for they believe that temples are just for funerals. But in fact it’s very necessary to go while you’re alive. A temple should not be something connected only with death, but with life.

What do you think the Zen monastic experience can offer that cannot be found in, say, the Tibetan or Greek or other monastic trainings?

I think that the comparison between a Catholic monastery and a Zen monastery is a very good one. But training in a Zen monastery is a little like running a 100-meter dash, whereas training in a Catholic monastery is like running a marathon. A Catholic monk enters a monastery for life. However, for a Zen monastery, the minimum length of stay is only three years — though there’s no upper limit. Even if you’re in a monastery for 10 years, it’s only one part of your life. However, in the time that you are in the monastery, it’s a very severe, concentrated kind of training. So while a Catholic monastery does clearly have a very religious way of life, it does not have this kind of concentrated training period.

For me, the way of the Catholic monk has a certain charm. It’s not a case of which religion is good or bad; there are just two ways. As to which is better for you, you must choose freely.

Still, I do think the severity of Zen produces good results. In the Zen way of training, in which you don’t think about likes or dislikes, you’re able to concentrate on developing the fundamentals.

However, there is one problem with the Zen system, and that’s the three-year minimum length of stay. I think that this is a bad rule. I think it would be better to be in here for 10 years — that’s the ideal, I think.

How would a monk in his 10th year be different from a monk in his 3rd year?

In 10 years, a Japanese monk can usually finish all his koan studies.

But in terms of behaviour, what would be the difference?

For the monk who’s only been in a temple for a year, the robes don’t really fit. By the third year, they begin to suit him. After 10 years, there’s no problem.

In my own case, for example, up until my third year of training, I still occasionally thought about my college girl-friend. By the fifth year, that had disappeared. So in my tenth year, even if I thought of my girl-friend, it did not present a problem.

By ‘severity,’ do you mean the physical hardship of living in a monastery?

One becomes used to the physical severity rather quickly. However, the spiritual severity is rather more difficult.

What is the most difficult lesson a monk can learn?

Cutting the ego! Look at the process whereby an aspiring monk must wait for seven days in the entrance-hall to gain admission to a monastery. Even that removes a little of one’s egotistical self. Some people who have graduated from, say, Tokyo University or Kyoto University, the two best colleges in Japan, develop a certain pride. In the course of applying for admission to a monastery, however, their egotism starts to fade away. It makes no difference where you come from — you have to sit for seven days in any case.

And often the very wish to become a purer person, or to lead a better life, can itself be an expression of the ego?

Right! When one thinks of human life, one sees that the ego is very strong. Sometimes there are people who do many things for others, yet fundamentally, they are still really doing them for themselves. In order to suppress this fully, 3 to 5 years is not enough.

If, for example, you wish to study very hard, I think that’s very good. But if you do it just in order to enter a good company, that’s not so good. And if you enter a company without the ultimate idea of helping people, I think that’s not very good at all. Anything you do with the idea of increasing your pride is a very bad attachment.

Baseball players, for example, do zazen in order to increase their powers of concentration. And when the power of concentration increases, so too does the power of remembrance. When I was still a student, for example, I could remember as far back as when I was 3 years old. But after spending some time in the monastery, I began to remember things that happened to me when I was, say, two and a half years old. And because these kind of memories come forth, lots of things start coming into your head, and the ego becomes very strong. So by cutting off these ideas as they come forth, you can start to do good zazen by the third or fourth year. So the longer you stay in the monastery, the better.

How do you think Zen can help the average man — the typical American, say, who’s never had any contact with a Zen center?

Modern Japanese are in too much of a hurry to progress, to go forward all the time. When, for example, I go from Kyoto to Osaka, I can see that the people there walk a lot more briskly. And in America too, I have noticed that people in Kansas tend to walk in a more relaxed way than the people of Dallas or Los Angeles. Isn’t it true that people these days are in too much of a hurry? Most people think that this is only natural because everyone around them is doing the same thing. Thus one naturally thinks, ‘I don’t want to be behind everyone else,’ and so egotism naturally comes forth.

One effect of Zen for the average man is that it makes him stop and think. It’s like the one day of rest in the week. The reason for this day is to make you stop and calm down.

Like the Sabbath in the Jewish tradition?

Right! And one should use this ‘holy-day’ well, and to good advantage. Indeed, Americans probably use their free time better than Japanese: Japanese even go to work on holidays. Yet even during these holiday periods, the ego is often not stopped. There’s always a feeling of ‘I want to enjoy this holiday.’ And if you do not use that time to try to find yourself, I cannot really say that it’s a ‘holy-day.’ When you’re hurrying around too quickly, there’s a part of the world you cannot see. However, when you stop, you can see things. If, for example, you’re taking a wrong direction in your life, it’s only when you stop and look at things clearly that you can revise your direction and take a more proper course. So Zen teaches us that in order to find ourselves, we’ve got to learn to stop.

Pico Iyer is a prolific author and regular contributor to Kyoto Journal.