As a child growing up in the American Midwest in the early 1960s, I experienced the kitchen as a place of large, gleaming domestic appliances. There was the toaster; the large white fridge that let out a sigh when its door was opened, as if reluctant to divulge its contents; and the cooker with four burners and a large oven, its capacities massively underexploited as my mother used it mostly just to heat up the so-called TV dinners she was fond of serving us.

That kitchen was a place that would have been unrecognizable to our ancestors, who cooked basic, unprocessed ingredients over open fires.

I left the comfortable and unchallenging world of my childhood when I was in my early twenties, eventually settling in Japan where I married a farmer. We are resident in rural Shikoku, and I have got acquainted with the roots of cooking through my relationship with my husband’s mother, whom I call Okaasan.

The kitchens she knew as a child and toiled in as a young married woman were at no far remove from the earliest of places set aside for the preparation of food, those we glimpse when we watch documentaries about living arrangements still prevalent in certain third-world countries, where someone—nearly always a woman—is squatting before a fire, stirring the contents of a pot, feeding twigs or grass to the flames.

Okaasan has lived all her life in an old traditional Japanese farmhouse: a building with black mud-wattled walls that huddles under a heavy grey tile roof, sited in a dusty courtyard enclosed by high stone walls. Okaasan grew up in one such house, surrounded by rice paddies, to move, in her mid-twenties, to another, ten kilometers distant, surrounded by orange groves, on her marriage.

My husband recalls that such traditional old Japanese farmhouses were built to face south for the light. The northeast corner was reserved for the kitchen: east, to take advantage of the sun, and north, to diminish the impact of the sultry summer heat. The well was dug near the kitchen. The toilet was sited in the southwest corner of the house, as far as possible from the place where food was prepared and eaten.

The kitchen of the hundred-year old house Okaasan moved into as a bride was a large, dark space with a hard dirt floor. There was no refrigerator or stove, and electrical equipment was limited to a single light bulb dangling from the ceiling. Okaasan and her mother-in-law cooked over a wood-burning brazier. My husband remembers that, from his earliest boyhood days, he was expected to collect twigs and branches from the slopes of the mountain a half-kilometer from the house for the kitchen fire and for the fire that would heat the family bath.

I think the Japanese have a peculiar genius for making a virtue of necessity. In the case of food, with no gas or electric stoves at their disposal, countless generations of Japanese in past centuries perfected the art of grilling and roasting meat and fish, of stewing vegetables over a low flame, and of preparing exquisitely presented platters of raw fish and vegetables. With no refrigerators or freezers to chill food, they became adept at pickling a wide variety of vegetables to complement the daily fare of rice. Sweets were provided in the form of dried fruit. In autumn, it is still not uncommon to see a line of dried persimmons strung out like a festive line of yellow Christmas-tree bulbs on the porch of a Japanese farmhouse.

My husband talks of having had to share a single egg with his brother at breakfast when they were children. The rest of the eggs provided by the family’s poultry needed to be sold. He had few sweets. But there was always enough to eat and all of it of good quality or, as we would say now, ‘locally sourced.’ Their vegetable garden supplied okra, cucumbers, tomatoes, potatoes, onions, leeks, lettuce and daikon. There was also a strawberry patch, and a line of fig trees bordered one orange grove.

When we first met, the Japanese man I would marry was dismayed at what he obviously perceived as my ‘bad food’ habits. He refused to accompany me to the local McDonald’s, for example, ascribing my fondness for fast food at that time to my being an American. As a Japanese, he was raised in a far different way than I had been, and with quite different ideas about food and about eating.

Accustomed to the strong flavors of Western food, I found it difficult to adapt to the milder, more subtle tastes of Japanese cuisine. As a child in America, I was a devotee of root beer stands and hamburger joints. I loved the warm buns cradling succulent thick patties, their salty meatiness complemented by slices of tomato and lettuce and lashings of mayonnaise, ketchup and mustard. Soft drinks were the perfect accompaniment, the intense sweetness of the drink contrasting with the saltiness of the food.

But, over the years, my palate adjusted, my interest in Japanese food heightened by the prominence it played in daily life. In my first years in Japan, I was surprised by the large number of cookery programs on television and the popularity of shows featuring attractive young girls traveling about the country, sampling regional culinary delights.

After thirty years here, I am still struck by the reverence Japanese display towards food, something I never encountered in America. I am moved by the Japanese custom of prefacing and ending mealtimes with a set phrase indicating gratitude. The habit of pressing the palms together, as if in prayer, before uttering these phrases imparts a worshipful air. I attribute this attitude towards food not only to Japan’s native religion Shinto, which recognizes the presence of god or a divine spirit manifesting in nature, but also to the food deprivation of the war years, when even farmers like Okaasan’s family faced starvation. When we first got acquainted, I was surprised by Okaasan’s habit of eating with a sort of furtive haste and relish, a practice I later observed in others of her generation.

When I was growing up in a small town in the middle of America, I had little direct connection with food. It was something that was packaged in boxes or covered with cellophane wrap that we bought on weekly shopping expeditions to Sam’s grocery downtown. We would fill a shopping trolley with goods and load all the bags in the car to take home. As my mother was an indifferent cook, we often had meals of processed food that needed only to be heated: pizzas, TV dinners, pot pies. There were cases of Coca Cola in a refrigerator in the basement. The freezer was packed with ice cream, the cupboards with cookies and crackers and tins of soup and vegetables and fish.

Although she was content to serve us such fare, my mother had a very different relationship with food when she was a child, and one that was not at such a far remove from Okaasan’s. My maternal grandparents owned several large farms in central Indiana. They grew tomatoes for a local ketchup factory as well as cultivating fields of corn for animal feed and soybeans. There were pigs and cows and horses.

Like Okaasan, my mother’s mother cooked with fire, preparing her meals on a big iron wood-burning stove. Light was provided by kerosene lamps. There were no flush toilets. Any water to be used for cooking or baths had to be pumped by hand. There was a large pink pump with a trough situated in one corner of the kitchen, and a windmill just outside.

My elder brother and two elder sisters and I would spend at least a month each summer at what we thought of as the paradise of our grandparents’ farm. Grandma used to give each of us a saltcellar, and we were invited to stroll through the tomato fields to select a juicy, ripe and sweet tomato and eat it as if it were an apple. I recall, too, excursions to the cornfields, when Grandma would hastily pick an armful, entrusting a few ears to each of us children, and we ran back to the farmhouse, husking the corn as we ran, to throw it into the pan of boiling water on the stove. Grandma stressed the importance of cooking the corn as soon as possible after it had been picked to ensure its greatest sweetness and flavor.

In my own family, my grandmother’s culinary skills were not passed on to the next generation. I attribute this partly to my mother’s being the lazy spoilt darling of the household. The women of my mother’s generation felt they had been liberated from the slavery of household chores. They relished the abundance of processed food: meals made in factories, that could be bought at stores and heated in an oven, were meals they need not prepare in their own kitchens.

When I return to America, I am horrified by the prominent role fast food or convenience food or ready meals plays in everyone’s life. I also feel aghast at the waste of good food that everyone seems to take for granted. When I visit the homes of friends or relatives and happen to be asked to fetch something from the refrigerator, I am greeted by the spectacle of an appliance packed full of cartons and boxes and bags of food, with items retrieved from the rear often in a state of advanced decay.

My practices as the manager of a kitchen in Japan are quite different. Without consciously intending to, I find I have adopted many of Okaasan’s and my grandmother’s habits. Like them, for example, I keep poultry. We have nine plump brown hens and one intimidatingly large and fierce white rooster. We can usually get seven or eight freshly-laid eggs each morning.

My husband, like Okaasan’s and my grandmother’s, is a farmer. We eat the fruits of his labors. He returns home most summer evenings with bundles of onions with dirt still clinging to their roots or with bags of tomatoes or okra or with heads of lettuce that he deposits on our kitchen counter for me to prepare as I will. Naturally, we are well-supplied with citrus fruit: not only with mikan, the small, sweet Japanese oranges, but also with navel orange, a fruit called dekopon and limes.

Like Okaasan and my grandmother, I try to use every scrap of food we have. When summer’s bounty results in more fruit and vegetables than we can possible use, I present the surfeit to friends and colleagues. I make a point of keeping the fridge only half-full, determined that nothing in it should be thrown away. Any peelings or rinds or scraps are given to the poultry.

I work in a Western-style kitchen imported, with our log house, from America. I cook with a large range with four burners and an oven rather than over an open fire. I enjoy modern conveniences Okaasan and my grandmother could only have dreamed of: a rice cooker, a toaster, a coffee maker and a microwave. But I try to maintain their tradition of using seasonal ingredients to prepare delicious meals and to make my kitchen the heart of our home.

We humans are fond of imagining that what we call ‘progress’ proceeds in a linear fashion. However, the modern age is characterized by an abundance of food for the inhabitants of ‘developed’ nations, including processed goods with a long shelf-life but containing questionable ingredients. We live in a world of plenty, but we are eating too much and eating the wrong things, leading to the recent explosion in cases of obesity and diabetes, heart disease and strokes and various kinds of cancer. It is chastening to reflect that the individuals who endured the war years of the mid-twentieth century, who were forced to significantly limit calorific intake, were healthier than us, and that the generation growing up today is the first in centuries whose life expectancy is predicted to fall below that of the generation preceding it.

My American grandmother was active in cultivating her vegetable and flower gardens until her early seventies, and Okaasan was picking oranges and sorting and packing them until her mid-eighties. They enjoyed good health until advanced old age. My own parents, on the other hand, both contracted adult-onset diabetes in their fifties, no doubt largely attributable to their habit of drinking large quantities of soda and their fondness for packets of cookies and store-bought cakes.

I have read that nearly a third of British homes nowadays lack a dining room table. In our current reliance on fast food and packaged ingredients, our preference for the ‘ready meal’ as opposed to making dishes ‘from scratch,’ we have lost sight of where food comes from. It strains credulity, but studies have shown that many inhabitants of so-called advanced countries do not know, for example, that cattle supply beef let alone dairy products, that potatoes grow underground, or that apples ripen on trees.

Whether in Japan or in America, we ignore the example posed by our thrifty, hard-working and active forebears at our peril. We need to re-establish the centrality of the kitchen in the home and observe regular mealtimes. We should accord food its proper importance in our daily lives: living to eat, not eating to live. Domestic science classes for both boys and girls should be reinstated in schools. We must learn to understand where food comes from and become proficient in preparing it in ways that will nourish our bodies and minds. The adoption of such measures represents no step backwards, no retreat to a romanticized past. Our lives depend on it.

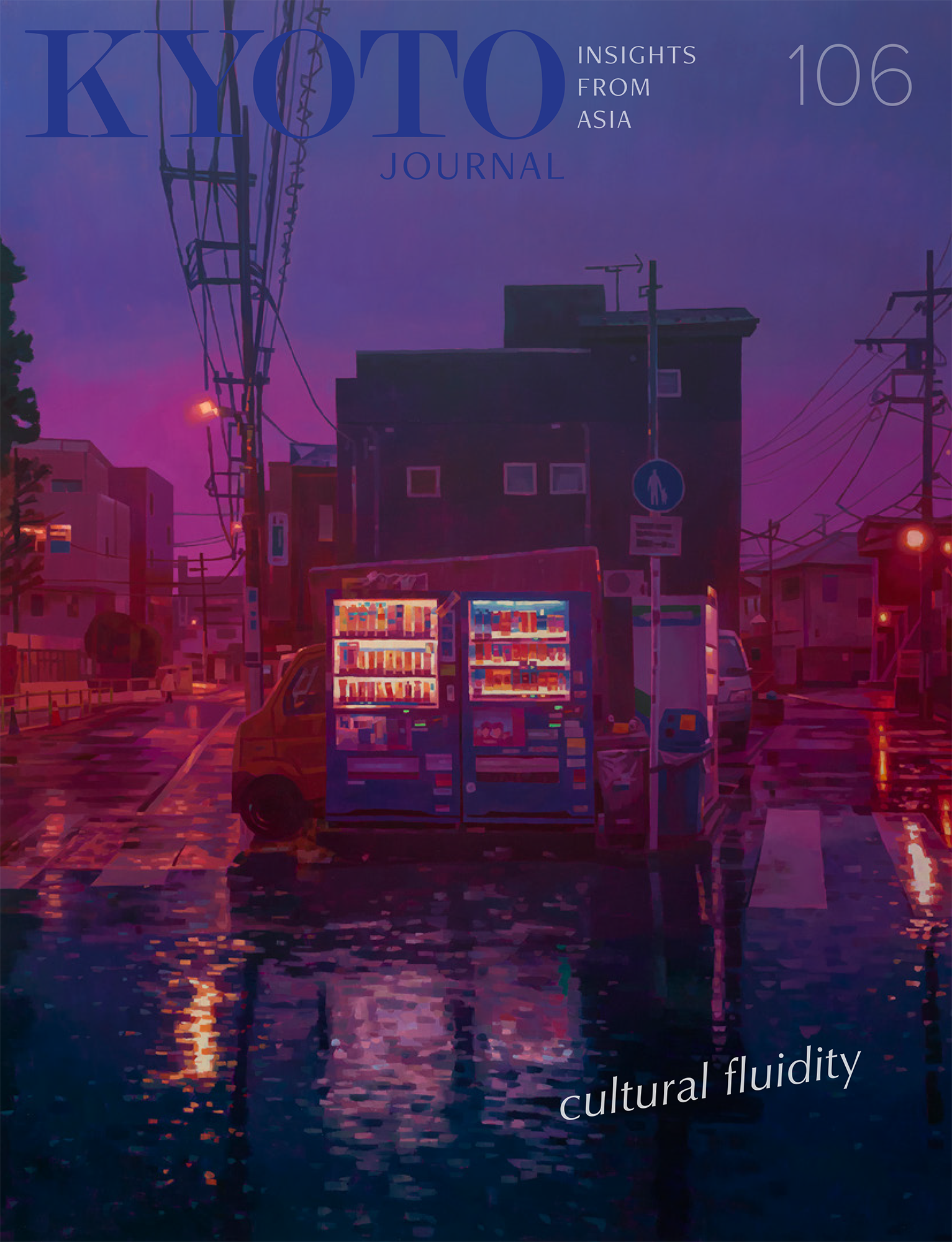

KJ93: Food is out now.

Author

Wendy Jones Nakanishi

Author's Bio

Wendy Jones Nakanishi, an American by birth, has been resident in Japan since the spring of 1984, since earning her doctorate in literature at Edinburgh University. She has been employed full-time since her arrival, first for five years at Tokushima Bunri University and now at Shikoku Gakuin University. She has published extensively on 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st-century literature and also, in recent years, writes on her personal experiences as a foreign woman, an academic, the wife of a Japanese farmer and the mother of three sons, inhabiting a rural area of Japan.

Credits

Illustrations by Yasmin Flett