“Field”: the ‘i’ of inaka; also pronounced ‘den’ or ‘ta’ (rice field):

den-so: rice tax

den-en: rural district

den-gaku: ancient music

den-enshi: pastoral poet

ta-go: a peasant

ta-i: rice-field well

ta-mushi: ringworm

ta-ue: rice planting

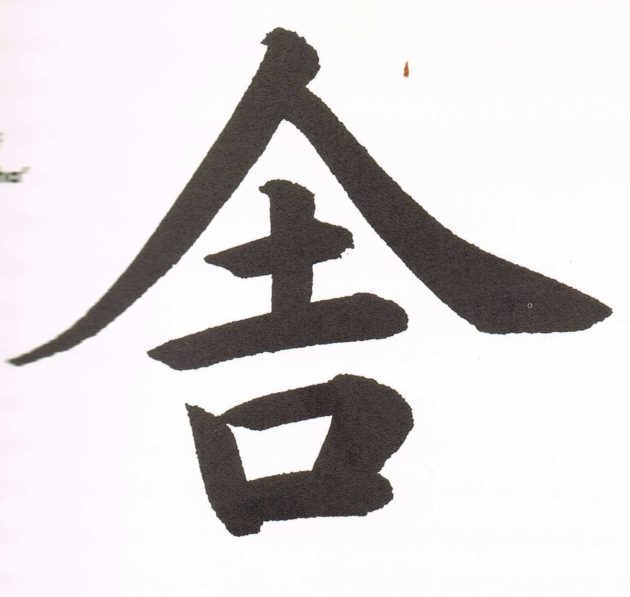

“Lodging”: the ‘naka’ of inaka; also pronounced ‘sha’ (inn):

i-naka-ben: provincialism

i-naka-fu: rural manners

i-naka-kusai: countrified

i-naka-sodachi: country bred

i-naka-ya: rural cottage

sha-taku: residence

sha-kei: elder brother

sha-ri: bones of the Buddha

Millions of Japanese and thousands of foreign visitors come annually to Kyoto and Nara, drawn by the chance to venture beyond the awesome metropolis of Tokyo and to sample the well-sung pleasures of “Japanese culture.” In geographic, historical, cultural or ecological terms, few of those who come so far have more than a faint idea about what they are seeing. A step or two away from the city, and the tourist is lost.

This is at odds with the general approach towards culture elsewhere. No true measure of Italy, after all, is possible without a taste of the campagna. Subtract the plains and prairies of the heartland, and American arts and letters lose their meaning. If one thinks of Japanese civilization as a great tree, the most brilliant blooms and succulent fruits adorned branches represented by the cities Nara and Kyoto. To fully appreciate those flowers and fruits one must follow the course of investigation right to the roots. These are firmly set in the soil of the inaka, approximately in English, ‘countryside.’

The translation is less than perfect. The English word implies a shunting of the ‘country’ to the ‘side,’ but says nothing of what actually happens there. Inaka is formed of two characters for ‘field’ and ‘lodging,’ which suggests days spent beneath the sky and nights around the hearth. It offers the specific image of a landscape in which humans take part, by working ‘fields’ and building ‘shelter,’ thereby instituting culture. The English term has come to carry a heartwarming gloss, to connote a sanctuary ‘aside’ from the urban jungle. The Japanese word is less explicitly nostalgic; it emphasizes a rhythm of manual work and repose.

Hegel spoke of a quantifiable relationship between natural beauty and “that which is spiritual,” an idea that has always found enthusiastic support among Japanese scholars. When Hirata Atsutane instituted the first formal studies of Japanese nativism in eighteenth century Edo he called his school the Ibuki-ya, borrowing the name of the peak on the Lake Biwa shore. His nineteenth and twentieth century heirs Tsuda Sôkichi and Karaki Junzô analyzed the Japanese view of nature in terms of the history of ideas and spiritual beliefs. Watsuji Tetsurô, the most illustrious of their peers, pioneered the methodical observation of landscape, and particularly climate, for the spiritual and emotional effects these produced upon the viewer, and went on to demonstrate their influence on art, architecture and philosophy.

Other languages provide deep conceptual tropes for land in the pastoral sense: the German Heimat (home), the Malay bumi (soil) and the Hebrew adama (earth, from which comes the name Adam) all carry psycholinguistic associations that make them more potent than mere conversational tools. They approximate the Japanese words sato, tsuchi and chi, words of specific concrete identity that are common modifiers for literally hundreds of common words. Sato (variously ‘village’ and a unit of spatial measurement) finds its way into the compounds that spell ‘milestone’ and ‘taro potato’; it is also etymologically related to the word for ‘reason.’ The character tsuchi (soil) appears in words as various as ‘climate’, ‘Saturday,’ ‘paradise’ and ‘wrestling ring.’ Without chi (earth) the terms for ‘surface,’ ‘post,’ ‘geography’ and ‘hell’ could not be written. These three characters, in modified pronunciation, add poetic dimension to many names, such as Mariko, Dôi and Tsukiji. Indeed, the vast majority of Japanese names refer to natural or geospatial objects.

Another word that links man to place is the Chinese guo, meaning country or realm. In its Japanized readings koku and kuni its meaning may be stretched to the lofty level of ‘state’ or narrowed to the site-specific ‘birthplace.’ The various characters in which kuni has been written at different times are, in chronological order, ‘protect by force,’ ‘landmark,’ and the current ‘jewel,’ each inscribed within an enclosure, recalling the German umfrieden, to “put at ease,” which means literally “to surround with a border.” Ancient interpretations of the word kuni included ‘earth,’ ‘ground,’ ‘district’ and ‘castle.’ Place names such as Kunii and Yoshino-no-Kuni (Province of Yoshino) are found at archetypal landscapes in which a flat area is surrounded by green mountains and traversed by clear streams.

The case of inaka is different. The twin characters give it a greater emotional scope, so that the field/shelter nexus can be made to carry an arcadian gloss in one instance, a derisory stain in another.

In the current, highly commercial condition of Japanese civilization inaka has a slightly repellent quality. It implies a lifestyle inferior to that of the city (ichi, literally ‘market,’ an exciting place where goods are bought and sold). Thus a lack of sophisticated entertainment facilities in a small town is admitted in terms of it being inaka-ppoi, left behind. A person from a rural area is an inaka-mono, literally a ‘country thing,’ meaning bumpkin. The English word ‘outlandish,’ meaning untenable, is perhaps comparable to this. In the 1950s, when over half of the Japanese population lived country lives and many more could recall a rural childhood, the stigma attached to the term was diluted by a sense of kinship among the many people to whom it could possibly be applied. But the current figure is 20%, and country people now cannot be blamed for feeling looked down upon. “The image of home, or homeland, in Japan today is laden with existential connotations,” wrote the environmental engineer Higuchi Tadahiko in a 1975 study of rural landscapes, “and with the eminently contemporary question of alienation, loss of homeland.”

The grouping of the population into ever-inflating urban centres has been matched by little of the Thoreauvian—or Blakean, or Tolstoyan—sense of ‘return’ to enriching roots. Nor is there a conspicuous move to develop futuristic paddy-girthed residential zones to counterpart the floating cities and reclaimed islands that will constitute new Japanese landscapes in the new century (although the historic ceramics district of Shigaraki and agricultural Wakayama have experimented with future-oriented temporary expositions). A formidable geographic profile has limited any serious development in these directions. In the place of utopianism there is the concept of fumi no sato, a sympathetic echo of the idyll expressed by Izaak Walton in “The Compleat Angler,” wherein urban man dips a toe from time to time from the therapeutic stream of rural existence. City dwellers who enjoy landscape painting, fishing or picking seasonal vegetables are well informed about where they must go to feel the embrace of nature. The increased availability of motor vehicles is matched by a surge in the number of young couples to whom country motoring has become a rite of courtship.

In a country notable for its art the landscape is still the greatest gallery of all. When the Japanese gardeners and artists of the past expressed ideal landscapes they painted and sculpted from natural models which are still recognizable today in rural Kinki, in much the same way as we can still see the lovers, autocrats, thugs, fools and other stock types of traditional theatre around us in the street. Classic Japanese art and literature would not have come into existence without the nourishing cocoon of the hinterland. The very last page of the premier classic of Japanese letters, the twelfth century Tale of Genji, contains a warning of sorts for those with the eyes to see. It is a poem about being lost in the mountains.

Purchase the Inaka: Japanese Countryside issue as part of our discounted Nature & Sustainability in Japan Bundle