LANE DIKO

Interpretation and translation: Yamada Mariko

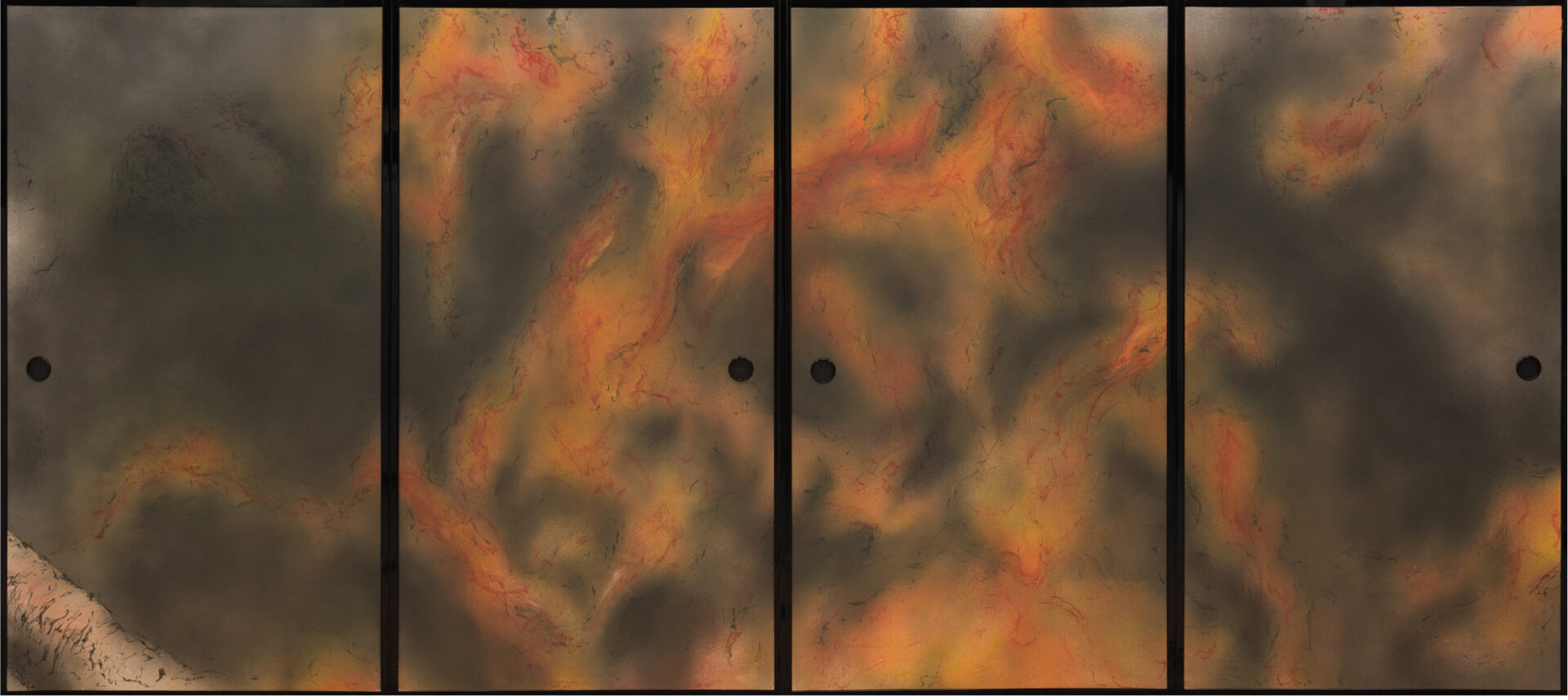

Gigantic salamanders, monstrous fish, chimeric tigers… In his portrayal of such fantastic beasts, the painter Niwa Yuta draws on a long artistic tradition of expressing the awesome power of nature through metaphoric visual language. In his dark, swirling paintings, Niwa combines modern and traditional styles to create images which are both playful and frightening. These large-scale works are often presented in the traditional forms of byōbu folding screens and fusuma-e sliding screen paintings. Some are semi-photographic renderings of the aftermaths of modern disasters: overturned boats, bent telephone poles, and fragile, kindlinglike houses. These almost documentary scenes are juxtaposed with images of great inky, stormcloud forms, creatures which fill the entire frame yet are at the same time shrouded and nebulous.

Niwa grew up in Tokyo, and moved to Kyoto to attend the Kyoto University of the Arts. It was in Kyoto that he first encountered the giant Japanese salamander, or ōsanshōuo, which is not found in eastern Japan. “I went to the Kyoto aquarium to look for inspiration for my classes, and was very surprised to see this large black creature that I had never seen before.” Niwa explained that in the Edo era Japanese people could only imagine the form of animals such as elephants and tigers, based on folk-tales, literature, and rare pelts that arrived from distant lands. When he first saw the ōsanshōuo, he felt the same sense of wonder. “That was the beginning of my work. I had never seen this creature before, and the surprise of this encounter led to my creation.”

Niwa also studied in Geneva, Switzerland, where there were no courses in Japanese painting. “I feel that this time overseas made me consider what Japanese art really was.” Attempting something he had never tried before, Niwa created a ceramic piece depicting the ōsanshōuo. This time abroad convinced Niwa that he needed to learn more about the Japanese aesthetic tradition, and upon returning to Kyoto, he created a new piece inspired by the work of the Momoyama period painter Hasegawa Tohaku, using the traditional materials of gold leaf and Japanese paper. “In Japan artists learn from those who have come before them and incorporate what they have learned into their own works.” This generosity of the Japanese artistic tradition is not a form of copying, but a cultural practice based on respect.

As Niwa began to explore the ōsanshōuo as a theme, he researched its history and discovered the tale of “Hanzaki,” about a giant, man-eating salamander over ten meters long from the Yubara hot spring area in Okayama prefecture. According to legend, when a villager was eventually able to slay the beast, his family was cursed by the monster. A shrine, Hanzaki Daimyojin, was built to assuage its vengeful spirit, and remains to this day. During festivals, a salamander-shaped mikoshi is paraded around the shrine. The story of this monster became both a symbol of and warning against flooding and disaster. The ōsanshōuo would have been well-known fauna in this part of Japan, so by imbuing this familiar creature with such frightening power, the legend was able to give a comprehensible form to invisible and inexplicable disasters. “I wanted to pursue this theme because I was fascinated with the idea of the people of Japan, a land where there are so many disasters, ascribing them to these giant creatures.”

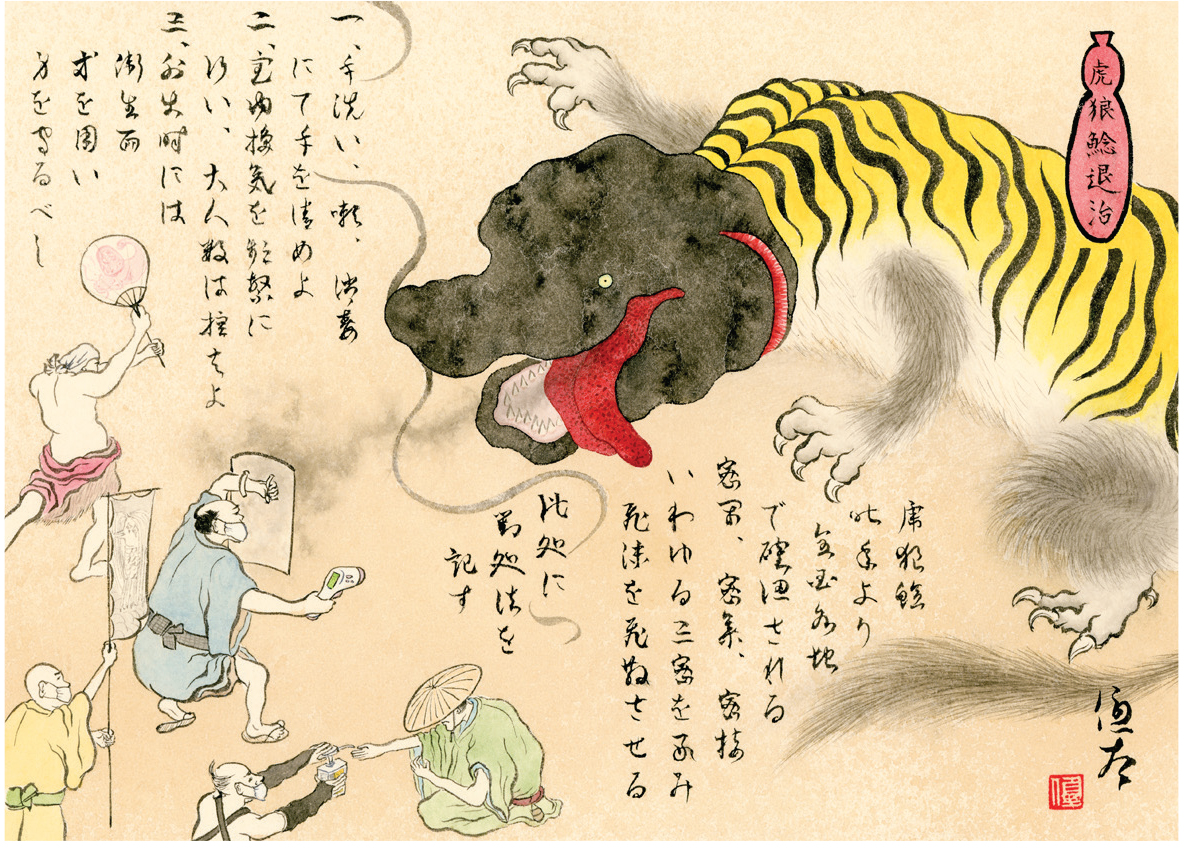

Just as the bounty and beauty of nature may be portrayed in religious iconography, in the forms of gods or kami, the destructive forces of nature are also given form through art. Earthquakes and disease in particular have no outwardly visible cause, making them that much more fearful and requiring entirely fanciful representations. Japanese legend tells of a gigantic catfish which lives within the earth and causes earthquakes. After several major earthquakes towards the end of the Edo era, ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) of catfish, known as namazu-e, became popular. To this day the catfish is synonymous with earthquake preparedness in Japan and is used as the ‘Earthquake Early Warning’ logo of the Japan Meteorological Agency. The Ainu of Hokkaido have a similar story of a great primordial trout which causes the tides with its breath and earthquakes with its shaking. Following cholera outbreaks of the Edo period, the invisible, mysterious disease was portrayed as a fantastic beast with the head and fore-legs of a tiger, the body and hind-legs of a wolf, and the giant testicles of a tanuki (raccoon-dog). “The idea is to give form to invisible fears, and perhaps to overcome those fears with humor.”

These depictions might seem humorously antiquated to modern eyes but Japan’s traditional zoomorphic folklore is still alive in modern popular culture, from the films of Miyazaki Hayao to Godzilla, whose popularity reflected an inchoate fear of nuclear war and pollution. “I have always loved Godzilla since I was a child, and had a large collection at home… my parents once saw one of my works and asked me if it was Godzilla!” In fact, despite prodigious scientific advancement, the invisible forces shaping our world today—from nuclear power to global warming—remain as difficult to visualize and comprehend as they would have centuries ago. In 2020, Niwa intended to continue his studies in Beijing, but was forced to return to Japan because of the coronavirus pandemic. “I have been addressing coronavirus as a subject since I came back from China.” Inspired by the Edo-era ukiyo-e, he created a piece called “Korona-mazu,” depicting a chimeric monster and the hand-sanitizer and face-shields used against its toxic breath.

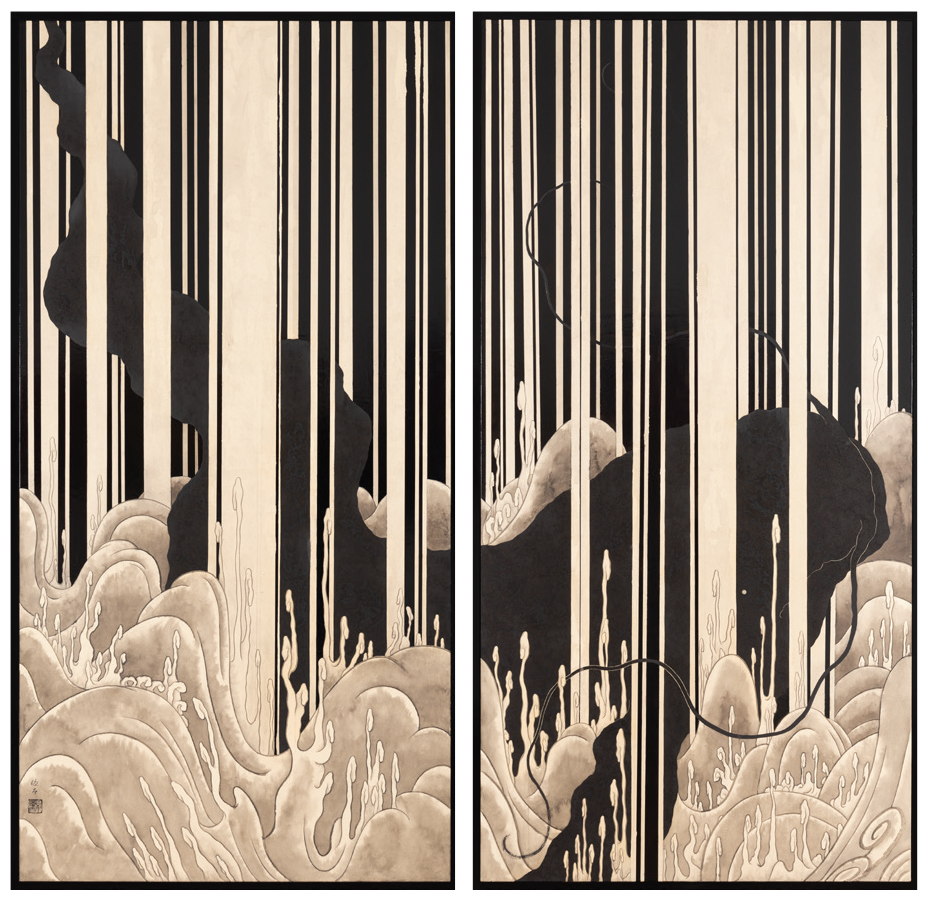

After returning from China, Niwa took up residence at Kōshō-ji Temple in Uji, Kyoto. “I was looking for a place to paint large works and I lived at the temple, doing zazen meditation in the mornings and evenings and painting during the day.” At Kōshō-ji, Niwa created large-scale sumi-ink paintings of animals representing the power of the coronavirus: a tiger, a wolf, and a tanuki. However, because of the pandemic restrictions, no exhibition was held. It was decided that the work should be displayed as part of a ceremony to pray for an end to the pandemic. Although he now lives in Tokyo, Niwa’s relationship with Kyoto continues to deepen. In order to continue his ceramic work, Niwa began to work with the Toan kiln, near Tofukuji Temple. Through Toan, he was then introduced to the priest of the nearby Komyo-in, a subtemple of Tōfuku-ji. “As I was working at the potter’s hermitage, a short walk from Komyoin, I would often spend my breaks there and started to build a good relationship with the priest. It was through this series of connections that I was able to first exhibit at Kōmyo-in.” Niwa staged a major exhibition of fusuma-e paintings there in 2021, and is now in preparation to create twenty-four new sliding door paintings for two rooms at Kōmyo in. “It has been a dream of mine to exhibit in a permanent space such as a temple, but I didn’t expect it to happen so soon in my career. The work will start in April of 2022 and will take about a year to complete. In the first room, I plan to paint an image of a large black creature in waves, with water flowing from a waterfall into the garden designed by Mirei Shigemori. I am inspired by the fusuma-e at Kompira-san Shrine in Kagawa Prefecture. The plan for the second room is influenced by Hasegawa Tohaku. I would like to take this opportunity to pay homage to those whom I admire.”

“When we look at nature, we may see it as divine. But there are times when we portray it as evil.”

American photographer and artist LANE DIKO has been a regular contributor to KJ as a writer, photographer, and editor. His work has been featured in VSCO, and he has exhibited at The Terminal KYOTO and EV Gallery in New York City. A solo exhibition of his work was held in 2024 at Ace Hotel Kyoto as part of Kyotographie/KG+.

NIWA YUTA’s fusama-e paintings are on display at Komyo-in Temple and nearby Kaho Gallery for the month of November 2025.