[pullquote]Tradition is something that needs to be created, not simply protected. If we are to protect anything, it is nature itself, which supports tradition.”[/pullquote]

[Y]ears of war, genocide and misrule devastated the Cambodian economy and society, leaving most Cambodians poor and focused only on survival. The cataclysms that swept away millions of lives also destroyed the land, burning forests and riddling the soil with countless landmines. Declaring “year zero” the Khmer Rouge willfully tried to strip the nation of its rich culture and heritage. Today, in concert with efforts to rebuild shattered lives, some projects aim to restore arts such as music, dance and architecture. The casualty that Japanese expatriate Morimoto Kikuo is trying his hardest to save is Cambodia’s traditional art of silk weaving and dyeing. At its heart, Morimoto’s is an eco-cultural enterprise bringing back lost skills as well as the vanished raw materials they require, once plentifully provided by the land.

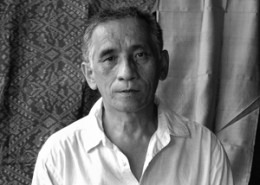

As with many who possess deep wisdom, it is nearly impossible to get a straight answer from Morimoto. In his gentle voice and quick laugh, he illustrates with vignettes instead of dry explanations. “Wisdom from the Forest” is the tangible culmination of what all these stories mean to Morimoto: a project to revitalize war-torn Cambodia’s environment, people and textiles.

Siem Reap, a town and regional center famed for its proximity to Angkor Wat, is home to Morimoto’s non-governmental organization, the Institute for Khmer Traditional Textiles, founded in 1996. It’s commonly called “IKTT,” a wordplay on the term for the pre-dyed silk weavings known as “ikat.” Thirty kilometers north of Siem Reap is Chot Sam, about 23 hectares of land where his Wisdom from the Forest project is located — a new and nearly self-sufficient village with about 500 residents of different ethnicities and backgrounds, each doing a small part of the huge operation of creating splendid silks from scratch.

Born in Kyoto in 1948, Morimoto grew up the son of a factory guardsman who kept a vegetable garden on the factory grounds. The young Kikuo’s own career began with a five-year apprenticeship in the yuzen technique of dyeing and painting kimono. Earning only “tobacco money,” a small stipend barely enough to live on, he spent it mostly on dyes and brushes, trying constantly and in vain to copy his master’s work. Morimoto pored over the man’s books of original Edo-period works, and drew inspiration from pictures, fabrics and kimono at the Kyoto National Museum. He became, in his own right, highly skilled.

Born in Kyoto in 1948, Morimoto grew up the son of a factory guardsman who kept a vegetable garden on the factory grounds. The young Kikuo’s own career began with a five-year apprenticeship in the yuzen technique of dyeing and painting kimono. Earning only “tobacco money,” a small stipend barely enough to live on, he spent it mostly on dyes and brushes, trying constantly and in vain to copy his master’s work. Morimoto pored over the man’s books of original Edo-period works, and drew inspiration from pictures, fabrics and kimono at the Kyoto National Museum. He became, in his own right, highly skilled.

Eventually, his interests reached outside of Japan to Thailand, where he volunteered in refugee camps in 1983. He taught hand-weaving and natural dyeing in projects there until 1995, when UNESCO asked him to help in the revival of ikat in Cambodia. He went and he stayed, founding IKTT and starting the Wisdom from the Forest project, which earned him the Rolex Award for Enterprise in 2004.

[pullquote]Sometimes he asked about a

technique surpassing her

years, spanning back to her

mother’s or grandmother’s

generation. Om Chia would

try to remember and

together they would attempt

to figure it out. [/pullquote]

The project started small. He bought five hectares of land from the mother of one of his staff members. He had very few workers on his staff, but recalls that this made it possible for the project to grow naturally: “If at the beginning I had four or five hundred, it would’ve been impossible, but in the beginning, I just had five, and working under one of them were two more.”

In Morimoto’s projects, everything grows naturally. For silk made in Chot Sam, the beginning of the process is in the land: “A good soil gets a good color. We have cows for natural fertilizer, to improve the soil. After that, we plant mulberry trees, cotton trees, indigo trees, and (for food) vegetables and fruit trees.”

He brings the trees or their seeds — some having gone wild — from other parts of Cambodia for planting at Chot Sam. Locally the trees essential to creating silk, like the mulberry that the silkworms feed on, were cut down or burned during the war. In order to dye the silks naturally, which Morimoto insists on, lac insects are also needed to produce a vibrant red, characteristic of Cambodian ikat and unrivaled by chemical dyes. However, the finicky lac breed only in very specific conditions, which he is recreating at Chot Sam.

Besides the decimating of forests, during wartime the Cambodians lost many agricultural traditions. “They know how to survive in war. But it’s not a normal situation… They lost those normal life experiences,” Morimoto says. It took him one or two years to teach his staff to grow and harvest their own vegetables. In addition, the village owns about a dozen cows.

Continually looking to help the environment, Morimoto wants to make Chot Sam entirely sustainable and self-sufficient. Currently, the village buys propane and uses electric generators, but he wants to switch within the next year to biogas and a small hydro-electric generator using the excess rainy season water.

Although it took years of research and preparation before Morimoto’s wisdom took root in the forest, at first he faced a tight deadline: “In ’95 I had just five months to research the situation. Exactly how, where and what kind of textile we needed. Also, I had many questions. I found specialists in sericulture, specialists in spinning. I wanted to complete the research, but I didn’t have the budget. So I asked the Toyota Foundation and they helped me. I got that farmland (near Siem Reap) and I continued to do the research for about two to three years more.”

Part of that investigation included searching Cambodia for someone who remembered the old ways of silk weaving. Finally he discovered a grandmother and master weaver named Om (“old woman”) Chia.

Om Chia had survived many hardships in her life due to illness and war. She’d had three marriages and raised five daughters. When Morimoto approached her to ask for help, many of her fellow villagers regarded him with suspicion. They questioned why she would reveal the secrets of weaving to an outsider.

Om Chia, however, recognized Morimoto’s love for traditions and textiles. She respected his motivation to produce textiles the correct way, not the easy way, using natural colors, preparing the soil and planting trees. For ten years Morimoto relied on her wisdom and weaving knowledge. Sometimes he asked about a technique surpassing her years, spanning back to her mother’s or grandmother’s generation. Om Chia would try to remember and together they would attempt to figure it out.

Being new to Cambodia, Morimoto still struggled with the language, though he now speaks Khmer, Thai and English. He recalls that Om Chia “understood my feelings” and jokes that their communication “was not so good, but it was possible!”

After surmounting the language barrier, he found more tangible obstacles buried in the ground of Cambodia: landmines strewn throughout the country. His village has only experienced one explosion, but Morimoto once found a TNT cache used to make rockets and weapons. Which is why there is one staff person — a retired soldier — in charge of getting rid of the leftovers of war.

“We have many specialists working together. About cotton, about the silkworm, about the weaving, about the dyeing, about the life, how to care for the kids, how to care for the cows…”

Living the artisan’s life in Kyoto helped him style the system he now uses at Chot Sam. In Kyoto, the kimono-making process requires numerous differently-skilled craftsmen, each contributing to the final piece through specialized steps. Likewise, in Chot Sam, the 500 workers are divided into 24 groups, each with specialties. All are connected and treated equally, since every step is important to getting a fine piece of silk.

In addition to the manufacturing of silk, a carpentry group makes weaving tools such as looms and builds traditional-style wooden Cambodian houses. A 75-year-old carpenter who spent about eight years working for Morimoto began teaching other young and old men, so that a ten-person group now continues after the leader has retired. Another five workers constantly make banana ash, used as a dye, since the ash formerly bought from other villages caused uneven coloring.

In Morimoto’s vision, everyone works together cooperatively and equally. He accepts anyone, his weavers coming from Takeo and Kampot provinces in Cambodia, Khmer and Cham ethnicities, and Chinese and Vietnamese as well. He describes it as diverse cultures, “different backgrounds, working together,” with a common goal of survival. To achieve that goal, they must be willing to mix and share traditions.

“I always say that tradition is not only for preserving; we also create a new tradition. This is my basic belief,” Morimoto says. Bringing together the Khmer and Cham is one example of Chot Sam’s new traditions. As Morimoto deepened his research, he saw a great difference in the weavings between these two distinct ethnic groups: The Khmer favored small designs and motifs, similar to the Edo period Japanese komon. The Cham, however, used big patterns.

Morimoto noticed that the Khmer weavers had trouble copying some of the ancient patterns that might have come from the Cham hundreds of years ago and realized that their sense of beauty was so different that they couldn’t reproduce them. He began integrating the Muslim Cham group into a workshop with the Khmer. Not only could the Cham copy the Khmer patterns, but combining the Cham’s and Khmer’s opposite senses of beauty has created textiles that are altogether new, with a unique loveliness. Now, at least 20 Cham women are training in his workshop.

Currently, Morimoto’s village is so full that when a man or woman asks to join he adds their name to his waiting list and then waits for them to come back. If they do, Morimoto knows they are the kind of person who will contribute to beautiful textiles. “Those people have stronger motivation. This is very important to me,” he says. “I have just 500 people, but their power is double that.”

This does not, however, mean constant overwork. In fact, Morimoto will never push any of his staff to do anything, instead supporting and nourishing their interests. He calls this philosophy “物を作る心” (mono wo tsukuru kokoro) — the love of making fine work. As is his way, he explains his philosophy with a story: One of the women showed an interest in learning English, so Morimoto lent her a foreign children’s book. Eventually, her interest grew to the point that he gave her money to learn English in a school. She also learned to do math, so he asked her to become the village’s accountant. He gave her a computer, which someone taught her to use. Still, she wanted to learn even more, so Morimoto paid for her to go to a computer school. She subsequently made an English-Khmer dictionary for handling receipts, and she now takes care of the accounting for the textile village, using Excel spreadsheets.

All of the profits generated from the beautiful textiles go directly back to Chot Sam to pay the salaries of the workers and cover living essentials, a complete change from the system in place before Morimoto arrived. Formerly, middlemen controlled the market for textiles, keeping weavers and artisans in poverty. They were paid very low prices for their finished work, which was sold for high prices to consumers. Nowadays, due to the unique mixture of backgrounds and sensibilities in the textiles being produced at Chot Sam, those middlemen find it impossible to cheaply replicate the works in the operations they still control.

Morimoto emphasizes that in Chot Sam even young trainee artists who are years away from having the skills needed to produce marketable work are paid a salary. “We take a risk. We spend that money. The return may be five years, ten or twenty years later, but if we don’t have these people we don’t have a future.”

To make sure everyone can take part in the work, Morimoto has learned to make working more convenient for the villagers. For example, the daily demands of caring for a household and baby had kept one young woman from attending Morimoto’s weaving center, even though her house was only one hundred meters away. “Now I accept the woman bringing the baby with her,” says Morimoto. “If she leaves her baby at the house, she is always worried sick. If the child is with her, she has no need to worry and she can concentrate on making good work.”

Nevertheless, Morimoto’s plans are far from completion. He admits that currently it is impossible for native Cambodians to buy the fabrics because of the price. Only foreign buyers can afford to appreciate the fabrics from Chot Sam. They come from all over the world, including Japan. Morimoto’s institute has a branch in Tokyo and another in Germany. IKTT Germany may hold an exhibition for the fabrics next year to raise support for the weavers. Morimoto makes sure to specify that these support groups are not donors, but buyers.

The job of the IKTT Japan spokesman is to create opportunities for selling the work, not to ask for handouts. He believes this is the only true “fair trade” policy, one where the Cambodian weavers create high-quality, beautiful textiles and then consumers, recognizing the value of the work, wish to buy them. He emphasizes that there must be risk involved in a “fair trade” endeavor. On the Rolex Award website, Morimoto is quoted as saying, “Without risk, neither good art nor anything else worthwhile will happen.”

His risk is also in believing that hearts intent on producing good work will continue the project until a more prosperous future for Cambodia arrives, when its people can once again take pride in themselves owning well-made traditional textiles.

“Their living condition, and salary, from just five years ago until now, is improving. In ten years, twenty years, if Cambodian people want to buy their traditional fabric, but there is no one to produce it — lost already, gone — it is very sad. Now, the (Cambodian) people say our products are very expensive and impossible to buy. But this is not correct.” He compares the situation to ownership of kimono in Japan. Prices limit most families to owning only one or two kimono during a lifetime, but they take pride in those few garments because of their fine quality.

In Morimoto’s book, Bayon Moon, he writes of old Cambodia silks: “Textiles woven by people who felt such attachment to their raw materials and tools are proof of the spirit that existed in this country, that revered textiles as culture and tradition at the heart of daily life.”

As he works to rekindle that spirit, Morimoto mourns its loss in Japan as well. The rich traditions of the kimono he studied in Kyoto seem now to be fading. “It’s not normal people’s work.” Referring to his own master, whose knowledge of materials and brushes led to the detail Morimoto found impossible to emulate, he adds, “I couldn’t reach my master’s level.”

The textile renaissance that started around the 15-16th century — the time of Oda Nobunaga and the revitalization of the Gion Matsuri by rich Kyoto craft and merchant guilds — has reached its end, according to Morimoto. To produce a new textile renaissance, he says, Japan needs “new thinking,” such as a return to the use of natural materials instead of the cheap fabrics bought from China. In the past few years, he has noticed a small revival of natural fibers in Japan, which he does his best to encourage.

Before WWII, many Kyoto kimono artisans went to Indonesia both to learn and to teach. Many Indonesian sellers today make products using the Kyoto kimono motifs. Likewise, Morimoto wants to inspire young artisans worldwide and finds hope in stories of retired Japanese craftsmen starting textile projects in Myanmar, India, Nepal and China. Even though these projects have had mixed success, he sees the efforts as most important. Older artisans transfer knowledge to the next generation. “It surprises me that they want to try. This is good, I think,” he says. “I hope for the next generation to grow, so I give a seed or something small.”

People familiar with Morimoto, and his altruism, would disagree that his gift is small. He expands on his eco-cultural philosophy in Bayon Moon: “Tradition is something that needs to be created, not simply protected. If we are to protect anything, it is nature itself, which supports tradition.”

Molly Harbarger is a senior at the University of Missouri studying journalism and international studies. She interned with Kyoto Journal while studying abroad in Japan. She has written for local newspapers The Columbia Missourian and Perry County Tribune.