Photographs by Lane Diko

Spring has come again to Kyoto, and the Kyotographie International Photography Festival (KG) has adorned the city for the thirteenth time with a program that challenges expectations of what is considered “art photography.” Performative self-portraiture and vernacular photography engage in dialogues with history, and critical cultural perspectives are presented with humor and creativity to engage both artists and the general public. “Kyotographie 2025: Humanity” has invited internationally recognized artists—including JR, Martin Parr, and Pushpamala N—to share their diverse perspectives, drawing visitors from around Japan and abroad, reflecting Kyoto’s place as a growing center of contemporary art in Asia. The festival comprises 14 major exhibitions, three associate exhibitions, dozens of public programs and Kyotophonie concerts. In addition, their partner festival, KG+, features an astonishing 131 shows, KG Select shows, and other special exhibitions around Kyoto City.

Kyoto Journal and KG have long had a special relationship. In 2025, however, KJ is itself part of the KG line up as an associate program. KJ’s founding editor, John Einarsen, was given Kyotographie’s first Lifetime Achievement Award last year for his contributions to the art of photography, which came with an invitation from co-founders Lucille Reyboz and Yusuke Nakanishi to mount an exhibition celebrating the magazine’s nearly 40 years of words and images: “Sharing Visions: The Heartwork of Kyoto Journal.”

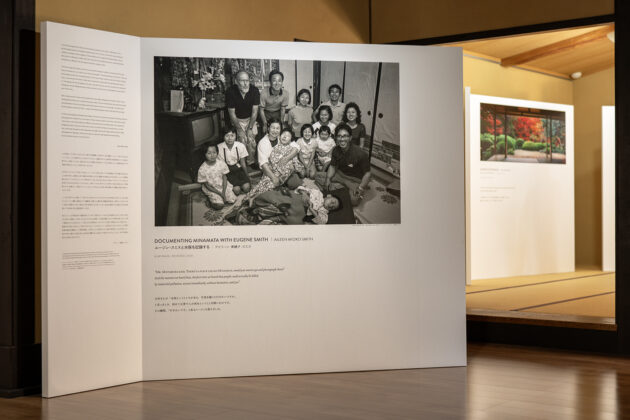

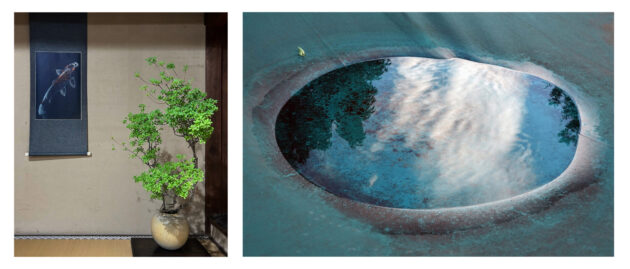

Curated by John Einarsen, Lane Diko, Reimi Adachi, and Susan Pavloska under the direction of exhibition manager Zoey Yi-Chun Lee, the exhibition features specially selected images that have appeared in KJ’s 108 issues to date, from 1987 to 2024. In collaboration with scenographer Spinning Plates, KJ’s design team, led by Hirisha Mehta, created byobu-style displays whose layouts reference the magazine format of text and images together. Each photograph is accompanied by its own unique story and its importance in the magazine’s history.

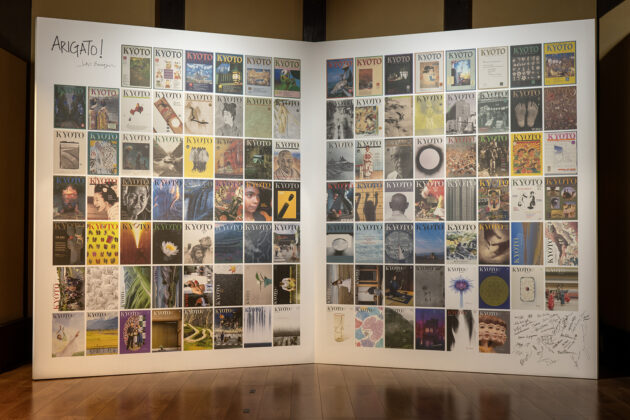

The exhibition—filling three rooms which surround a serene nakaniwa garden within the Shimadai Gallery, a historic former trading house in the center of the city—includes a large display of the covers of all 108 issues, a reading area in a tatami room overlooking the garden where visitors can peruse KJ back issues, and a documentary by filmmaker Felicity Tillack, featuring an extended interview with John Einarsen and other members of the KJ team and community. More photographs and their stories are displayed in wooden stands resting on the tatami floors, where visitors are invited to sit on zabuton cushions while viewing and reading. One of these is dedicated to the memory of KJ’s managing editor Ken Rodgers and includes a remembrance by frequent contributor Pico Iyer.

The images and stories encompass a wide array of styles and subjects, from fine art to journalism to science. They include Aileen Mioko Smith’s warm portrait of the Minamata family made famous through the iconic photographs by her late husband, W. Eugene Smith. One of Tōmatsu Shōmei’s haunting portraits of hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) accompanies excerpts from an essay by Arundhati Roy. A giant banner displayed across the gallery’s facade depicts Kyoto’s Jidai Matsuri procession (the cover of KJ 94), photographed by Czech/Canadian artist Tomas Svab with a unique, experimental camera. John Einarsen’s photography, influenced by the Miksang mindfulness approach, is given pride of place.

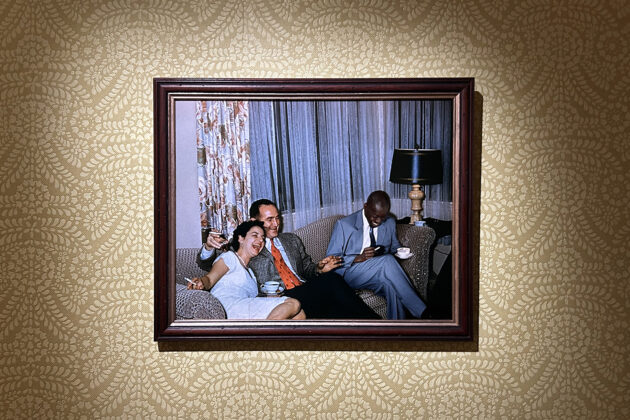

Kyoto Journal’s neighbor on the east side of Shimadai Gallery is the exhibition “Being There,” a collaboration between filmmaker Lee Shulman and photographer Omar Victor Diop. Within the same traditional Kyoto building, a replica of a suburban home from the United States of the 1950s has been constructed, complete with period furniture, carpets, wallpaper, and a Super 8mm film projection. The kura space has been transformed into a dining room with the Budweiser bottles and cigarette butts still left over from a party the night before. The effect is that of walking into a period film with a soundtrack by the Ink Spots and Ella Fitzgerald.

The many photographs on the walls of this home depict scenes from family vacations, parties, and domestic life of the 1950s, but with a subversive twist. Shulman merges his interest in vernacular photography, especially his large archive of anonymous slides, with Omar Victor Diop’s playful self-portraiture to craft a fantasy portrait of pre-Civil Rights America that is humorous, poignant, and disconcerting. In the photographs and ‘home movies,’ the artists appropriated real slides of white American families—vacationing, partying, and relaxing—and meticulously, digitally-inserted portraits of Diop, a striking African man, into each scene.

The carefree charm of the vintage images is indirectly superimposed with America’s dark history of racial terror and segregation: we know that these scenes of racial harmony would have been impossible. Viewers are put into an uncanny space—between a glimpse of an endearing fantasy and the living history of racial oppression at the heart of American culture—and challenged to consider our own present and possible futures. The exhibition is, on one level, genuinely delightful to experience and made even more haunting through this saccharine masquerade.

The international character of Kyotographie is on full display in this exhibition which is, as the artists themselves describe it, “a Senegalese guy and a Dutch guy creating an art exhibition about America in Japan.” Kyotographie’s curation has often highlighted African artists, especially West African, since its inception. The history of photographic portraiture in West Africa is long and deep, and has been explored in several previous KG exhibitions, including by Malick Sidibé in the first KG in 2013 and by Diop himself in 2020. When KG opened DELTA, a permanent multi-purpose space in the Demachi Shotengai shopping arcade, it also began an artists-in-residence program, hosting young African artists and exhibiting their work. In 2025 the featured artist was Ivorian photographer and activist Laetitia Ky.

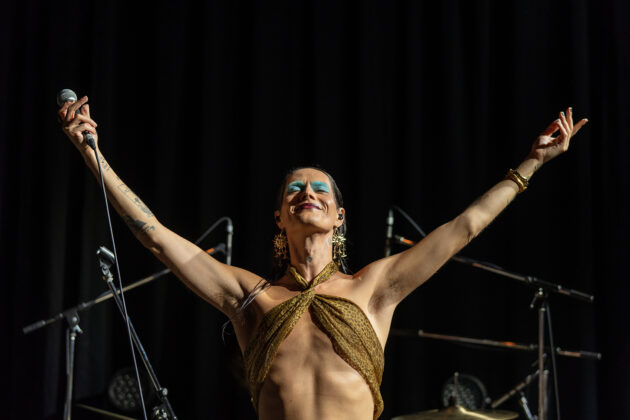

In Ky’s tongue-in-cheek self-portraiture, her hair is sculpted into various forms including everyday objects and symbols of female identity and empowerment. Her imagery—featured prominently in KG’s promotional materials, the Demachi Shotengai, and the “Love and Justice” exhibition at ASPHODEL—connects cultural heritage, identity, and daily life through the medium of hair. With intimate bonds formed through touching, grooming, and styling, hair is recognized as a subject, both personal and social, and a medium itself.

Although Ky is the literal poster artist of KG 2025, the star of the show is undoubtedly JR, the French street artist whose giant-scale public art pieces have developed into a global series of populist murals in the mold of Diego Rivera. After having created his massive photo-collages for cities such as New York and San Francisco, JR and his team visited Kyoto in autumn 2024, photographing residents in mobile studios all around the city. After an initial call for participants on social media drew a disproportionate number of foreign residents (especially French), they moved without public announcement to different neighborhoods each day, inviting random passersby to be photographed for the project. JR noted that Kyoto residents were especially hard to convince to participate. Once in the photo booth, however, they were natural and enthusiastic models. One family sitting along the Kamo River even allowed themselves to be cajoled into moving their entire picnic into JR’s mobile studio. To represent the diverse character of the city, JR also sought out subjects more directly. The Ohara morning farmers’ market was chosen as the place to find the city’s top chefs, and special photo sessions were arranged with cheerleaders, monks, firefighters, and drag queens.

In keeping with the egalitarian nature of the project, JR asked participants to choose their own clothing, pose, and accessories. To ensure equality of presence, everyone was photographed with the same lighting and focus. Along with the portrait sessions, short audio recordings were made of each participant introducing themselves and describing their lives. These voices of Kyoto can be heard, and the full “Chronicle of Kyoto” mural viewed in detail, at the JR Chronicles website.

The JR mural itself is installed at the entrance to Kyoto Station (at a size large enough to require a special exception from the city). Another exhibition at Kyoto Shimbun newspaper headquarters presents the overall Chronicles project with murals from several other cities. These are installed on curved walls sweeping through the utilitarian rooms of the newspaper’s former printing press, along with a making-of exhibition and documentary film. After passing through these displays, viewers enter the main hall of the former printing plant, a vast, industrial space unlike any stereotypes of Kyoto scenery. As they pass along a gangway, giant figures of Kyoto residents tower overhead, a nod to JR’s past public art projects.

While JR’s mural is packed with Kyoto residents, the city itself is filled with international and domestic travelers. Martin Parr’s “Small World” exhibition captures the absurdity, chaos, and kitsch of modern tourism. While his images are undeniably humorous, overtourism in Kyoto is no joke. Alongside iconic images from his long career, including books on the culture of the selfie, Parr unveiled a slideshow of new images documenting the height of Kyoto’s cherry blossom frenzy earlier this spring, set to a gratingly cheerful recorder tune. His works highlight what Kyotoites know all too well: the often-uneasy tensions between tourists and the communities they descend upon.

A highlight of the festival is a portrait of life in broader Palestine by the Palestinian American photographer Adam Rouhana. The photographs are simple, unpretentious images of families, fields, and daily life which hover between editorial journalism and personal travelogue. As with Diop and Shulman’s “Being There,” however, the warmth of the images is shadowed by our underlying awareness of a much darker reality. The exhibition’s setting on the 2nd floor of a traditional Japanese house, with tatami rooms overlooking an inner garden, is juxtaposed in viewers’ minds with the homes (or former homes) of Palestinian families. Recordings of conversations and everyday sounds of life in Palestine play throughout the rooms. The scenography in this exhibition space, as in past years, is especially impressive. Large scale images are displayed on the floors and in the place of sliding fusuma panels. One small piece that stands apart from the others is a photograph of a photograph: a portrait of the artist’s Christian-Palestinian family taken on a Palm Sunday in the 1970s.

Mao Ishikawa’s nearby exhibition, “Red Flower,” also presents a personal document of life in an occupied territory. Her intimate black and white photographs from the 1970s document the interactions of Okinawans—her friends, family, and acquaintances—with the American soldiers stationed on the island, which was officially under U.S. military occupation until 1972.

In “Dressing Up” the Indian artist Pushpamala N, like Diop, Parr, and Ky, uses performative self-portraiture and humor to break the ice of ‘fine art’ and political issues. Her work combines the melodrama of vintage movie stills with compositions appropriated from European Neo-classical paintings to tell deconstructed stories about gender, race, nationalism, and colonization. Stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata are enacted for the camera by the artist and her friends with a puckish sense of humor. She poses as cultural figures (Mother India), religious icons (the goddess Kali), and historical personages (Vasco da Gama) with costumes and hand-painted backdrops that have the feel of an amateur traveling theater. The references to painters like Ingres and Fuseli are well suited to the grand building, The Museum of Kyoto Annex, a designated Important Cultural Property.

A powerful exhibition, in terms of both content and scenography, is of the career of Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide. Her striking black and white images capture the depth of the rituals, symbolism, and contradictions of Mexico, as well as those of the human condition more broadly. Iturbide spoke of the difficulty in selecting the best images to convey the internal poetry that define her career, a celebration of life and death. The artist’s son, architect Mauricio Rocha, designed the exhibition as a cross-cultural dialogue, blending the warmth of Mexican stucco walls with Japanese washi paper.

Irish photographer Eamonn Doyle also addresses themes of family, life, and death, grappling with the enduring bonds of familial love in the afterlife. His work, which reflects on transcendence and grief, finds a natural home in the spiritual setting of Higashi Hongan-ji Temple’s O-genkan space. In 1999, the artist’s brother suddenly passed away at the age of 33, and over the following 18 years, his mother wrote letters to her deceased son, which were only discovered after her own passing. In the exhibition “K,” images of the letters are layered into dense, abstract compositions, forming a visual tapestry of maternal grief and enduring love. An otherworldly soundscape, based on the keen, a traditional Irish funeral lament, echoes through the chamber, accompanying photographs of mysterious, shrouded figures. Cloaked in wind-blown fabric, these forms resemble boulders shaped by the wind. Their presence is haunting and elemental, as if a spirit had briefly embodied the cloth, just long enough to be photographed, and then disappeared.

Kyoto Journal and Kyotographie are both vibrant cultural institutions, founded by Kyoto outsiders and expats who adopted the Old Capital as their new home. They bring the world to Kyoto through their international perspectives and represent Kyoto to the world in deep and surprising ways beyond the superficial and clichéd. Over KJ’s 38 years and KG’s 13, both have also presented Kyoto to itself as a thriving mix of contemporary art and traditional culture. “Kyotographie 2025: Humanity” embraces the intimate and complex dimensions of the human experience—from the global issues of overtourism and displacement to fraught questions of identity, as well as the simple beauty of everyday life.

American photographer and artist LANE DIKO has been a regular contributor to KJ as a writer, photographer, and editor. His work has been featured in VSCO, and he has exhibited at The Terminal KYOTO and EV Gallery in New York City. A solo exhibition of his work was held in 2024 at Ace Hotel Kyoto as part of Kyotographie/KG+.

LEWIS MIESEN is a freelance writer and translator who resides in Kyoto. A lifelong traveler, he rode his bike for two months across Japan. He enjoys exploring cultures and making new friends from all over the world. In addition to writing for Kyoto Journal, he is also KJ Marketing Director.