Page Contents

[I] started climbing snowpeaks in the Pacific Northwest when I was fifteen. My first ascent was on Mt. St. Helens, a mountain which I honestly thought would last forever. After I turned eighteen I worked on ships, trail crews, fire lookouts, or in logging camps for a number of seasons. I got into the habit of hiking up a local hill when I first arrived in a new place, to scan the scene. For the Bay Area, that meant a walk up Mt. Tamalpais.

[I] started climbing snowpeaks in the Pacific Northwest when I was fifteen. My first ascent was on Mt. St. Helens, a mountain which I honestly thought would last forever. After I turned eighteen I worked on ships, trail crews, fire lookouts, or in logging camps for a number of seasons. I got into the habit of hiking up a local hill when I first arrived in a new place, to scan the scene. For the Bay Area, that meant a walk up Mt. Tamalpais.

I first arrived in Kyoto in May, 1956. Because the map showed Mt. Atago to be the highest mountain on the edge of the Kitano River watershed, I set out to climb it within two or three days of my arrival. I aimed for the highest point on the western horizon, a dark forested ridge. It took several trains and buses to get me to a complex of ryokan in a gorge right by a rushing little river. The map had a shrine icon on the summit, so I knew there had to be a trail going up there, and I found it. Dense sugi groves, and only one other person the whole way, who was live-trapping small songbirds. Up the last slope, wide stone steps, and a bark-roofed shrine on top. Through an opening in the sugi trees, a long view north over hills and villages, the Tamba country. A few weeks later I described this hike to a Buddhist priest-scholar at Daitokuji, who was amused (“I’ve never been up there”) and mischievous enough to set me up with a friend who had Yamabushi connections. I was eventually invited to join a ritual climb of the northern summit of Omine, the “Great Ridge.” As it turned out I was inducted as a novice Yamabushi (sentachi) and introduced to the deity of the range, Zao Gogen, and to Fudo Myo-O.

After that experience on Mt. Omine I took up informal mountain walking meditations as a complement to my Zen practice at Daitoku-ji. I spent what little free time I had walking up, across, and down Hieizan or out the ridge to Yokkawa, or on other trails in the hills north of Kyoto. I did several backpacking trips in the Northern Japan Alps. I investigated Kyoto on foot or by bike and found an occasional Fudo Myo-o — with his gathered intensity — in temples both tiny and huge, both old and new. (Fierce as he looks, he’s somehow comforting. There is clearly a deep affection for this fellow from a wide range of Japanese people.) I studied what I could on the Yamabushi tradition. What follows, by way of prelude to a description of a pilgrimage down the length of the Great Ridge, barely touches the complexity and richness of this rich and deeply indigenous teaching. My own knowledge of it is, needless to say, rudimentary.

It must have started as prehistoric mountain-spirit folk religion. The Yamabushi (“those who stay in the mountains”) are back country Shaman-Buddhists with strong Shinto connections, who make walking and climbing in deep mountain ranges a large part of their practice. The tradition was founded in the 7th or 8th centuries CE by En-no-Gyoja, “En the ascetic,” who was the son of a Shinto priest from Shikoku. The tradition is also known as Shugendo, “the way of hard practice.” The Yamabushi do not constitute a sect, but rather a society with special initiations and rites whose members may be lay or priest-hood, of any Buddhist sect, or also of Shinto affiliation. The main Buddhist affinity is with the Shingon sect, which is the Sino-Japanese version of Vajrayana, esoteric Buddhism, the Buddhism we often call “Tibetan.” My mountain friends told me that the Yamabushi have for centuries “borrowed” certain temples from the Shingon sect to use as temporary headquarters. In theory they own nothing and feel that the whole universe is their temple, the mountain ranges their worship halls and zendos, the mountain valleys their guest-rooms, and the great mountain peaks are each seen as boddhisattvas, allies, and teachers.

The original Yamabushi were of folk origin, uneducated but highly spiritually motivated people. Shugendo is one of the few [quasi] Buddhist groups other than Zen that make praxis primary. Zen, with its virtual requirement of literacy and its upper class patrons, has had little crossover with the Yamabushi. The wandering Zen monk and the travelling Yamabushi are two common and essential figures in No dramas, appearing as bearers of plot and resolvers of karma. Both types have become Japanese folk figures, with the Yamabushi the more fearful for they have a reputation as sorcerers. Except that the Zen people have always had a fondness for Fudo, and like to draw mountains even if they don’t climb them.

Yamabushi outfits make even Japanese people stop and stare. They wear a medieval combination of straw waraji sandals, a kind of knicker, the deer or kamoshika (a serow or “goat-antelope” that is now endangered) pelt hanging down in back over the seat, an underkimono, a hemp cloth over-robe, and a conch shell in a net bag across the shoulder. They carry the shakujo staff with its loose jangling bronze rings on top, a type of sistrum. A small black lacquered cap is tied onto the head. (I have a hemp over-robe with the complete text of the Hannya Shingyo brush-written on it, as well as black block-printed images of Fudo Myo-O, En-no-Gyoja, some little imps, and other characters. The large faint red seals randomly impressed on it are proof of pilgrimages completed. The robe was a gift from an elder Yamabushi who had done these trips over his lifetime. He had received it from someone else and thought it might be at least a century old.) Yamabushi will sometimes be seen flitting through downtown Kyoto begging and chanting sutras, or standing in inward-facing circles jangling their sistrum-staffs in rhythm at the train station while staging for a climb. They prefer the cheap, raw Golden Bat cigarettes. Yamabushi have a number of mountain centers, especially in the Dewa Sanzan region of Tohoku. Then there’s Mt. Ontake, where many women climb, and shamanesses work in association with Yamabushi priests who help them call down gods and spirits of the dead. At one time the men and women practitioners of mountain religion in its semi-Buddhist form provided the major religious leadership for the rural communities, with hundreds of mountain centers.

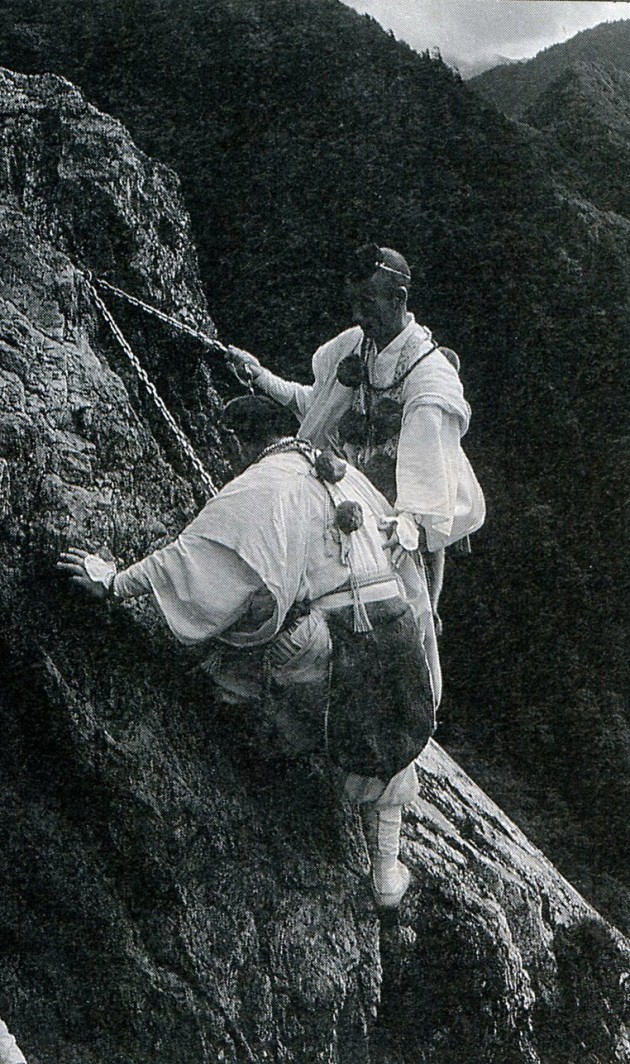

The “Yamabushi” aspect of mountain religion apparently started at Omine, in eastern Wakayama Prefecture, the seat of En-no-Gyoja’s lifelong practice. The whole forty-mile-long ridge with its forests and streams was En’s original zendo. Two main routes lead the seven or eight miles up, with wayside shrines all along the route. Although the whole ascent can be done by trail, for those intent on practice the direct route is taken — cliffs scaled while chanting the Hannya Shingyo. Near the top there is an impressive face over which the novices are dangled upside down. There are two temples on the main summit in the shade of big conifers. When you step in it is cooler, and heady with that incense redolence that only really old temples have.

A jangling of shakujo staffs and the blowing of conches in the courtyard between buildings.

A fire-circle for the goma or fire ceremony — mudras hid under the sleeves — and the vajra-handled sword brought forth. Oil lanterns and a hard-packed earthern floor, the uguisu echoing in the dark woods. A Fudo statue in the shadows,

focused and steadfast on his rock,

backed by carved flames,

holding the vajra-sword and a noose.

He is a great Spell-holder and protector of the Yamabushi brotherhood. His name means “Immovable Wisdom-king.” Fudo is also widely known and seen in the larger Buddhist world, especially around Tendai and Shingon temples. Some of the greatest treasures of Japanese Buddhist art are Fudo paintings and statues. His faintly humorous glaring look (and blind or cast eye) touches something in the psyche. There are also crude little Fudo images on mountains and beside waterfalls throughout central Japan. They were often placed there by early Yamabushi explorers.

A great part of the Shingon teaching is encoded onto two large mandala-paintings. One is the “Vajra-realm” (Kongo-kai) and the other the “Garbha-realm” (Taizo-kai). They are each marvelously detailed. In Sanskrit “Vajra” means diamond (as drill tip, or cutter), and “Garbha” means womb. These terms are descriptive of two complementary but not exactly dichotomous ways of seeing the world, and representative of such pairs as: mind / environment, evolutionary drama / ecological stage, mountains / waters, compassion / wisdom, The Buddha as enlightened being / the world as enlightened habitat, etc.

For the Yamabushi these meanings are projected onto the Omine landscape. The peak Sanjo-ga-dake at the north is the Vajra Realm center. The Kumano Hongu shrine at the south end is at the center of the Garbha Realm. There was a time when — after holding ceremonies in the Buddha-halls at the summit, the yamabushi ceremonists would then walk the many miles along the ridge — with symbolic and ritual stations the whole way — and down to the Kumano River for another service at the shrine. Pilgrims from all over Japan, by the tens of thousands, were led by Yamabushi teachers through this strict and elaborate symbolic journey culminating in a kind of rebirth. A large number of pilgrims now make a one-day hike up from the north end, a few do a one-day hike up at the south end, but it’s rare to walk the whole Great Ridge.

In early June of 1968 three friends and I decided to see what we could find of the route. My companions were Yamao Sansei, artist and fellow worker from Suwa-no-se Island, Saka, also an island communard and spear fisherman, and Royall Tyler, who was a graduate student at that time. He is now an authority on Japanese religion.

Early morning out of town. From Sanjo eki in Kyoto take the train to Uji. Then hitch-hike along thru Asuka, by a green mounded kofun ancient emperor’s tomb shaped like a keyhole, as big as a high school. Standing by quiet two-lane paved roads though the lush fields, picked up by a red tradesman’s van, a schoolteacher’s sedan — reflecting on long-gone emperors of the days when they hunted pheasants in the reedy plains. All ricefields now.

As we get into the old Yamato area it’s more lush — deeper green and more broadleaf trees. Arrive in Yoshino about noon — meet up with Royall & Saka (we split up into two groups for quicker hitching — they beat us) at the Zao Do, an enormous temple roofed old-style with sugi bark. A ridge rises directly behind the village slanting up and back to the massive mountains, partly in light cloud. Yoshino village of sakura-blooming hills, cherries planted by En-no-Gyoja (“ascetic” but it would work to translate it “mountaineer”) as offerings to Zao the Mountain King. In a sense the whole of Yoshino town stands as a butsudan / altar. So the thousands of cherry trees make a perennial vase of flowers — (and the electric lights of the village the candle?) — offerings to the mountain looming above. Here in the Zao Do is the large dark image, the mountain spirit presented in a human form, Zao Gongen — “King of the Womb Realm.” (“Manifes¬tation (gongen) of the King (o) of the Womb (za).”

I think he was seen in a flash of lightning, in a burst of mountain thunder, glimpsed in an instant by En the Mountaineer as he walked or was sitting. Gleaming black, Zao dances, one leg lifted, fierce-faced, hair on end. We four bow to this wild dancing energy, silently ask to be welcome, before entering the forest. Down at the end of the vast hall two new Yamabushi are being initiated in a lonely noon ceremony by the chief priest.

Zao is not found in India or China, nor is he part of an older Shinto mythology. He is no place else because this mountain range is the place. This mountain deity is always here, a shapeshifter who could appear in any form. En the Mountaineer happened to see but one of his possible incarnations. Where Fudo is an archetype, a single form which can be found in many places, Zao is always one place, holding thousands of shapes.

We adjust our packs and start up the road. Pass a small shrine and the Sakuramoto-bo — a hall to En the Moun-taineer. Walk past another little hall to Kanki-ten, the seldom-seen deity of sexual pleasure. Climb onward past hillsides of cherry trees, now past bloom. (Saigyo, the monk-poet, by writing about them so much, gave these Yoshino cherry blossoms to the whole world.) The narrow road turns to trail, and we walk uphill til dusk. It steepens and follows a ridge-edge, fringe of conifers, to a run-down old koya — mountain hut — full of hiker trash. With our uptight Euro-American conservationist ethic we can’t keep ourselves from cleaning it up and so we work an hour and then camp in the yard. No place else level enough to lay a bag down.

I think of the old farmers who followed the mountain path, and their sacraments of Shamanist / Buddhist / Shinto style — gods and Buddha-figures of the entrance-way, little god of the kitchen fire, of the outhouse, gods of the bath house, the woodshed, the well. A procession of stations, of work-dharma-life. A sacramental world of homes and farms, protected and nourished by the high, remote, rainy, transcendent symbolic mountains.

Early morning, as the water is bubbling on the mountain stove, a robust Yamabushi in full gear appeared before the hut. He had been up since before dawn and already walked up from Yoshino, on his way to the temples at the top. He is the priest of Sakuramoto-bo, the little temple to En the Mountaineer. Says he’s doing a 200 day climbing and descending practice. And he is grateful that we cleaned up the mess. The racket of a kakesu: Japanese Jay:

The Omine range as headwaters sets the ancient boundaries between the countries of Kii, Yamato, and Ise. These mountains get intense rainfall, in from the warm Pacific. It is a warm temperate rainforest, with streams and waterfalls cascading out of it. Its lower elevations once supported dense beech and oak forests, and the ridges are still thick with fir, pine, hemlock, and fields of wild azalea and camellia. The slopes are logged right up to the ridge edge here & there, even though this is in the supposed Yoshino-Kumano “National Park.” (National Park does not mean protected land wholly owned by the public, as in the U.S. In Japan and many other countries the term is more like a zoning designation. Private or village-owned land may be all through the area, but it is subject to management plans and conservation restrictions.)

On the summit, center of the Diamond Realm, we visit the two temple halls, one to En the founder, and the other to Zao. He makes me think of underground twists and dips of strata, the deep earth thrust brought to light and seen as a slightly crazed dance. And like Fudo, he is an incarnation of deep and playful forces. In Buddhist iconography, sexual ecstasy is seen as an almost ferocious energy, an ecstatic grimace that might be taken for pain.

We blow our conch, ring our shakujo, chant our sutras and dharanis, while standing at the edge of the five hundred-foot cliff over which I was once suspended by three ascetics who then menacingly interrogated me on personal and Dharma points. In the old days, some stories say, they would just let a candidate drop if he lied or boasted. From the 7th century on no women have been allowed on this mountain. [Several college women who loved hiking changed that in 1969]. Elevation 5676 feet.

We descend from the summit plateau and are onto the branch trail that follows the ridge south. It is rocky, brushy, and narrow — no wide pilgrim paths now. We go clambering up the narrow winding trail, steps made by tree-roots, muddy in parts, past outcroppings and tiny stone shrines buried in kumazasa, the mountain “bear bamboo-grass” with its springy thriving erect bunches and sharp-edged leaves. We arrive at the Adirondack-type (open on one side) shelter called “Little Sasa” hut and make our second camp.

Rhododendron blossoms, mossy rocks, fine-thread grasses —

running ridges — wind and mist — it had rained in the night.

A full live blooming little tree of white bell flowers its limbs embracing a dead tree standing —

moss & a tuft of grass on the trunk.

The dead tree twisting — wood grain rising laid bare white —

sheen in the misty brightness. When a tree dies

its life goes on, the house of moss and countless bugs.

Birds echoing up from both steep slopes of the ridge.

And now we are in the old world, the old life. The Japan of gridlock cities, cheerful little bars, uniformed schoolkids standing in lines at castles, and rapid rattling trains, has retreated into dreamlike ephemerality. This is the perennial reality of vines and flowers, great trees, flitting birds. The mist and light rain blowing in gusts uphill into your wet face, the glimmer of mountains and clouds at play. Each step picked over mossy rock, wet slab, muddy pockets between vines. Long views into blue-sky openings, streaks of sunlight, arcs of hawks.

A place called Gyoja-gaeri — “Where the ascetics turn back”. For a rice-ball-lunch stop. These trails so densely overgrown they’re almost gone.

Now at Mi-san peak, the highest point along the Great Ridge, 6283 feet. Another place to stop and sit in zazen for a while, and to chant another round of sutras and dharanis. A little mountain hut a bit below the summit. White fir and spruce-mist blowing afternoon. Yellow-and-black eye of a snake. A fine polish and center line on each scale.

Here for the night. Tending the fire in the hut kitchen — open firepit on the dirt floor — weeping smoky eyes sometimes but blinking and cooking — sitting pretty warm, the wind outside is chilly. Lost somehow our can of sencha, good green tea. We have run onto our first hikers, the universal college student backpackers with white towels around their necks and Himalayan-style heavy boots. They had come up a lateral trail, and were shivering in the higher altitude cool. Hovering over the cook-fire stirring I mused on my family at home, and my two-month old baby son. Another sort of moment for mountain travelers

Oyama renge — a very rare flowering tree “Magnolia Sieboldii” found here.

A darshan, the gift of a clear view of, a Japanese Shika Deer’s white rump. Deep water deep woods wide. Green leaves — jagged and curved ones, a line-energy to play in. White-flowering low trees with red-rimmed glossy leaves.

We angle up an open flowery ridge and leafy forest to Shaka-dake, Shakyamuni Peak, and have lunch. Chant here the Sanskrit mantra of Shakyamuni learned in Nepal — “Muni muni mahamuni Shakyamuni ye svaha” — “Sage, sage, great sage, sage of the Shakyas, ye svaha.” Shakya means “oak.” Gautama’s people were known as the “Oak Nation.”

All this trip we have stayed over 5000 feet. Then stroll down a slope to the west into a high basin of massive broad-leafed trees, without a hint of any path, open and park-like. An old forest. A light wind rustling leaves, and a dappled golden light. Thick soft fine grass — Tibetan cat’s-eye green — between patches of exposed rock. A rest, sitting on the leaves: sighing with the trees. Then a sudden chatter shocks us — a rhesus monkey utters little complaints and gives us the eye.

(Old men and women who live alone in the woods, in a house with no trail or sign — characters of folktale or

drama —)

To hear the monkey or the deer leave the path.

And I realize that this is the stillest place I had ever been — or would ever be — in Japan. This forgotten little corner of a range, headwaters of what drainage? Totsugawa River? Is it striking because it is seems so pristine and pure? Or that it is anciently wise, a storehouse of experience, hip? A place that is full, serene, needing nothing, accomplished, and — in the most creative sense — half rotten. Finished, so on the verge of giving and changing.

Maybe this is what the Za of Zao’s name suggests — za (or zo — Chinese tsang) means a storehouse, an abundance, a gathering, or in esoteric Buddhism, “womb.” Sanskrit alaya, as in “storehouse of consciousness” (alayavijnana) or Storehouse of Snow: Himalaya. The three divisions of Buddhist literature are called zo. Pitaka in Sanskrit, “basket.” Baskets full of the wealth of teachings. Could it be analogous to the idea of climax in natural systems? (Translating “Zao” as “King of the Womb Realm” is the Imperial Chinese reading of his name. “Chief of Storage Baskets” would be the Neolithic translation. “Master of the Wilds” is the Paleolithic version.)

We walk back up to our packs. Down the east ridge, loggers are visible and audible high on the slope. Load up and push through sasa on down the trail. A view of a large hawk: some white by the head. Likely a hayabusa — falcon — to judge by its flight and dive.

(I find myself thinking we in America must do a Ghost Dance: for all the spirits, humans, animals, that were thrown aside.)

— And come on a small Buddha-hall below Shaka-peak. We slip into it, for halls and temples are never locked. It is clean swept, decked out, completely equipped, for a simple goma service, with a central fire pit, an altar tray with vajra-tools, all fenced off with a five-colored cord, and a meditation seat before the fire spot. We know thus that there are villages below from which ascetics climb to meditate here. We are nearing the south end of the Great Ridge.

Another hour or so later, the trail that was following the top of the ridge has totally disappeared into the kumazasa and brush. It has started raining again. We stop, unload, study the maps, confer, and finally decide to leave the ridge at this point. We take the lateral trail east, swiftly steep and endlessly descending, stepping and sliding ever downward. Go past a seven-layer dragon-like waterfall in the steady rain. Sloshing on down the overgrown trail, find leeches, hiru on our ankles, deduced from the visible threads of blood. They come right off — no big deal. And still descending, until dark, we arrive at a place called Zenki, “Front Devil.” (Zenki is one of Fudo’s two boy imp helpers. Somewhere there’s a place called “Back Devil.”) We camp in another damp wooden hut along the trail. Someone has kindly left dry wood, so we cook by smoky firelight, and I reflect on the whole Omine route as we cook.

We are not far now from the Kitayama River, and the grade from here will be gentle. The Kitayama flows to the Kumano, and goes on out to the seacoast, ancient site of fishing villages and Paleolithic salmon runs. It would seem likely that from very early times, neolithic or before, anyone wishing to travel between the pleasant reed-plains of Yamato and this southern coast would have followed the Great Ridge. No other route so direct, for the surrounding hills are complex beyond measure, and the Great Ridge leads above it all, headwaters of everything, and sinuous though it be, clear to follow. The mountain religion is not a religion of recluses and hermits (as it would look to contemporary people, for whom the mountains are not the direct path) but a faith of those who move simultaneously between different human cultures, forest ecosystems, and various spiritual realms. The mountains are the way to go! And Yamabushi were preceded, by a mix of vision-questing mountain healers and sturdy folk who were trading dried fish for grains. In a world where everyone walks, the “roadless areas” are perfectly accessible.

The humans were preceded by wildlife, who doubtless made the first trails. The great ridge a shortcut for bears between seacoast fish and inland berries? All these centuries Omine has also been a wildlife corridor and a natural refuge, a core zone, protecting and sustaining beings. A Womb of Genetic Diversity.

Next morning find the start of a dirt road going on down to the river. A pilgrims / hikers register on a post there, where we write “Sansei, Saka, Royall, Gary — followed the old Yamabushi route down the Omine ridge 5000 above the valleys walking 4 days from Yoshino and off the ridge at Zenki. June 11 to 16, 1968.”

By bus and hitch-hiking we make it to the coast and camp a night by the Pacific. Hitching again, parting with Saka who must head back to Kyoto, we make our way to the Kumano “new shrine”, Shingu. Dark red fancy shrine boat in the museum and an old painting of whaling. A coffeeshop has a little slogan on the wall, “chiisa no, heibon na shiawase de ii —” “A small, ordinary happiness is enough.”

Travelling on, riding the back of a truck. Up the Kumano river valley running parallel to cascades of cool sheets of jade riverwater strained through the boulders. Houses on the far side tucked among wet sugi and hinoki, we are let off directly in front of Kumano Hongu at dusk. Found a nook to make a camp in, cook in, sleep the night. Riverbed smooth-washed granite stones now serve as the floor of the god’s part of the shrine. Grown with moss, now that no floods wash over.

Then dreamed that night of a “Fudo Mountain” that was a new second peak to Mt Tamalpais in Northern California. A Buddhist Picnic was being held there. I walked between the two peaks — past the “Fudo Basketball Court” — and some kami shrines, (God’s House is like the house the Ainu kept their Bear in?) and got over to the familiar parking-lot summit of Mt. Tamalpais. I was wondering how come the Americans on the regular peak of Tarn didn’t seem to know or care about Fudo Mountain, which was so close. Then I went into a room where a woman was seated crosslegged, told she was a “Vajra-woman” — Vajrakanha — a tanned Asian woman on a mat, smiling, who showed me her earrings — like the rings of a shakujo. Smiled & smiled.

6.30 AM the next morning we enter the center of the Garbhadhatu at Kumano Hongu, “The Main Shrine at Bear-fields.” On a wood post is carved:

“The most sacred spot in Japan, the main holy ground of the Womb Realm.”

And it goes on to say that on April 15 every year a major fire ceremony is conducted here. Shinto, way of the spirits, outer; Buddha, way of the sentient beings, inner. It’s always like this when you walk in to the shrine and up to the god’s house. It is empty; or way back within, in the heart of the shrine, is a mirror: you are the outside world.

They say — Kannon is water — FudO is uplift — Dainichi is energy.

Mountain and Water practice. Outer pilgrimages & inner

meditations.

They are all interwoven: headwaters and drainages,

The whole range threatens & dances,

The subsiding

Mountain of the past

The high hill of the present

The rising peak that will come.

Bear

Field.

And poking around there, in back, we come on a carpentry shed, mats on the ground, and workers planing hinoki beams. With that great smell. We have run onto a miya daiku, a shrine builder, Yokota Shin’ichi. We chat at length on carpentry tools, and forestry, and the ancient routes of supply for perfect sugi and hinoki logs to be used in the repair of temples, and the making of sacred halls and their maintenance. I ask him how would one build a sacred hall in America? He says, “know your trees. Have the tools. Everyone should be pure when you start. Have a party when you end.” And he says “go walking on the mountain.” He gives us fresh fish, he was just given so much.

deep in the

older hills

one side rice plains

Yamato

one side black pebble

whale-spearing beach,

who built such shrine?

such god my face?

planing the beam

shaping the eave

blue sky

Keeps its shape.

Thinking,

“symbols” do not stand for things,

but for the states of mind that engage those things.

/ Tree / = tree intensity of mind.

We hitch-hike on up the Totsugawa gorge, cross the pass, and in some hours are out in the Nara prairies and ricefields. With ayu (“sweetfish”) and funa (a silver carp, a gibel; lyrinus auratus) given us by Shin’ichi-san — tucked into a cookpot along with shredded ice to keep it cool, arrive in Kyoto by train and bus by 9 PM. We hello and hug and all cook up the fish — and brown rice for our meal. And I hold the baby, crosslegged on the tatami, back from the Great Ridge, linking the home hearth and the deep wilds.

That was 1968. It is doubtless drastically changed by now. The Yamabushi have much given way to hikers and tourists. Roads, logging, and commercial tourist enterprises spread throughout the Japanese countryside. Japan has extended its baleful forest-product extraction habits to the world. We in North America have nothing to be proud of, however. In the twenty some years since I returned to Turtle Island we have worked steadily to reform the US Forest Service and private logging practices. We are finally beginning to see a few changes. Nonetheless, in these years since 1968 Northern Califor-nia, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and South¬east Alaska have been subjected to some of the heaviest logging and destruction of habitat in the twentieth century. As Nanao Sakaki ruefully suggests, “Perhaps we shall have to change Du Fu’s line to read “The State remains, but the mountains and rivers are destroyed.”

Gary Snyder, as one of the most influential writers of his generation, should need no introduction. Lauded by Jack Kerouac, he was already a legend in Beat days, when he was among the first wave of post-war gaijin students of Zen here in Kyoto. His deep interests in Asian traditions encompassed Daoism and shugendo, and his friendship with the anarcho-nature poet Nanao Sakaki was also important. Taking what he had learned here, he returned to the US and became a vitally engaged voice as poet and essayist in the long-established tradition still mislabeled as “counter-culture.”

KJ deeply appreciates Gary’s longterm support and friendship. We first published “Of All the Wild Sakura,” excerpts from his 1959 journals, in KJ 24 (Allure of the Exotic), followed by “Walking the Great Ridge Omine,” in KJ 25 (Sactred Mountains of Asia). His essay “Language Goes Two Ways” appeared in KJ 29 (Word), “Coyote Man, Mr President and the Gunfighters” in KJ 51, and “Writers and the War Against Nature” in KJ 62.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013