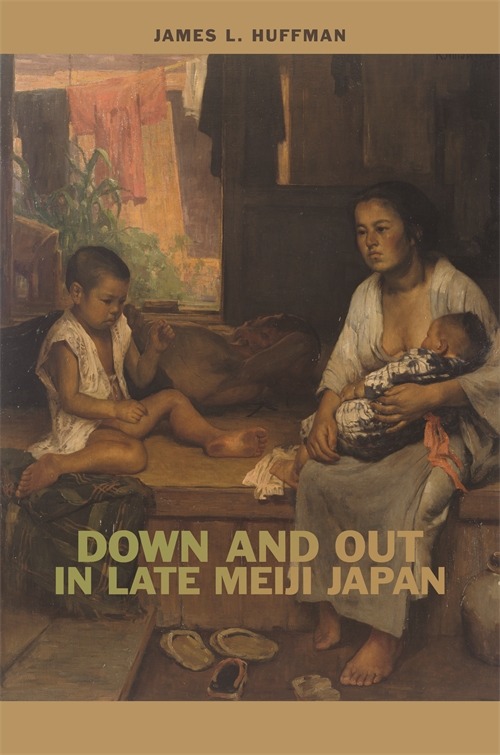

Down and Out in Late Meiji Japan by James L. Huffman. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 362pp., $68.00 (cloth).

James Huffman’s 2018 study of poverty in industrializing Japan is, in one sense, an extremely straightforward book. It seeks to answer that most naïve of historical questions: What was it really like to live in a certain time and place? What did one eat, wear, and think about? How did one work, love, and feel? Huffman focuses his inquiry on the very poorest of Japan’s urban poor—the hinmin, or paupers, who flooded into Tokyo at a rate of up to 1,000 people each week in the late 1800s and early 1900s, victims of government policies that pushed farm families to starvation and forced their sons and daughters to seek jobs in the swelling cities. By the early 1900s they made up between 12 and 20 percent of Tokyo’s population. They worked as matchbook-makers and rickshaw-pullers, prostitutes and porters, living in conditions that today seem hardly survivable. Huffman, a professor emeritus of Japanese history at Wittenberg University and a former journalist, is keenly aware of this gap between readers, writer, and subject—so much so that he explicitly asks what right he, a white middle-class American, has to explain the lives of poor Meiji Japanese. His slightly surprising answer is that a “peasant” childhood on a hardscrabble Indiana farm gave him the bone-deep empathy required to excavate his subjects’ lives without patronizing them. His aim, he writes, is simply “to understand how it felt to live the life of a hinmin.”

For all its simplicity, the task is not an easy one. The poorest of the poor walk quietly through history. Since few have the resources to tell their own stories in lasting ways, they must rely instead on outside observers often distracted by more glorious subjects. Fortunately for Huffman, the urban underclass was a popular topic for Meiji-era journalists like Mainichi reporter Yokoyama Gennosuke. Huffman draws heavily on newspaper reports of the day—particularly the sensational “page three” stories that many papers carried—to craft his Dickensian portrait.

One feature of the late Meiji era was that poor people began to cluster in slums, or hinminkutsu (literally “caverns of the poor”), instead of being scattered through cities as they were before. In Tokyo these slums were located overwhelmingly in the shitamachi neighborhoods of Asakusa, Shitaya, Fukagawa, and Honjo; in Osaka they were in Namba and Tennoji, and later, Nipponbashi and Kammagasaki. They were dirty, smoky, crowded, and—as Huffman is careful to point out—brimming with life. Streets thronged with beggars, peddlers, women cooking on outdoor grills, and children headed to work and school. For rural newcomers and ambitious bootstrappers, the energy could be thrilling.

Housing and food, on the other hand, were unequivocally miserable. The average mid-Meiji slum-dweller shared a two- or three-mat room with around five family members. Rent was paid daily, and it wasn’t unheard of for a poor laborer to pawn his quilt in the morning for a few sen, then pawn his jacket that same evening to get the quilt back to sleep under. The even less fortunate could rent a futon or strip of bare floor in a noisy, lousy (but sometimes companionable) flophouse. Food accounted for seven-tenths of the average household budget but consisted of little more than rice or gruel—although a bit of saké was considered essential. Quite a few hinmin shopped at “leftover food shops” that specialized in reselling scraps from military schools and barracks.

Commentators of the day attributed these miserable conditions to laziness and other moral defects, but their real root cause was the inadequate pay workers received in Japan’s budding capitalist society. Factory workers, cooks, clerks, and other bottom-rung employees worked ten to fourteen hours a day, most days a month, but still made far less than their basic needs demanded. This forced families to send women and children into the workplace, at pay rates even lower than men. The nature of work was changing, too. Artisans in particular lost their elevated status and became, in Huffman’s words, “links in the capitalist chain” forged by modernity.

Huffman’s portrait is much more nuanced than this, however. He constantly points out the agency the poor had over their lives, the diversity of their experiences, and the “slivers of light” in the “heavy layers of darkness” that made up their version of modernity—festivals, protests, camaraderie, and the hope of a better life. He offers endless quirky stories and factoids (What might one find alongside that quilt in the pawnshop? Why, stray cats, canaries, and a family mortuary tablet, of course). There is a comparative chapter on rural poverty, and one on the Japanese hinmin who labored on Hawaiian plantations. He has succeeded at what he set out to do: depict the poor not as pieces in some political or economic puzzle, but rather “as important in and of themselves, for their inherent worth.”

For close to a decade, Winifred lived in rural Japan, where she divided my time between writing, translating, growing organic rice and vegetables, and absorbing a second culture. She returned to the United States in 2014. www.winifredbird.com/