The muggy warmth of summer still lingers on an autumn night in Kyoto, Japan in 2019, as a lone figure sits at the piano, surrounded by about 200 Japanese and other guests sitting on floor cushions and folding chairs in a dimly lit wooden hall. The night air is perfectly still, punctuated only by the sounds of notes and chord progressions, and the spaces in between them, that South African pianist Abdullah Ibrahim is playing in a special solo performance on the grounds of Kamigamo Shrine, one of the oldest shrines of Japan’s indigenous Shinto religion.

A couple of side-panels on opposite sides of the shrine hall have been removed to help circulate the air, and in the middle of Ibrahim’s performance, the first drops of rain announce their arrival from the evening sky. Mildly at first, and then gradually into a percussion-like crescendo, the rain pounds the wooden roof of the shrine hall. Ibrahim plays straight through it, with the strains of “Blue Bolero” and his other past compositions in the hour-long suite accompanied by the sounds of the natural world, the open windows providing a surround-sound system of nature’s own making.

The crescendo of rain fades into a diminuendo, tapering off as Ibrahim plays on. In perfect sync, just as the last drops fall, the chirping of crickets and other night insects in the shrine grounds outside take over and begin to fill the room, a background choir to Ibrahim’s piano concerto. Something magical, almost mystical, is happening. By the time Ibrahim segues into the haunting strains of his song “Did You Hear That Sound” in the second set of the evening and looks out at the crowd for a connection, those gathered around him can only reply in a silent affirmative: Yes. Sound heard, minds moved, spirits transformed. Kiseki… kiseki-teki is how one Japanese staff member of the event’s organizing team later openly described the experience of the evening — a miracle, miraculous.

Ibrahim, at age 85, has played some of the biggest concert halls and most famous jazz music clubs in the world over the course of his long professional career in music since the late 1940s, accompanied by everything from small combos to full orchestras. But it is doubtful whether any of those storied venues and varied accompanists could compare to that autumn night on sacred ground in Japan, when a simple symphony of sound and nature’s own acoustics played out in harmony with an intimate solo piano performance by Ibrahim.

His music rests on a firm spiritual foundation. Those earliest influences in spirit can be traced back to traditional African culture and the Christian church under which he grew up in Cape Town, South Africa, and later on, in 1968, his conversion to the religion of Islam. But just as importantly, the culture and healing traditions of the Orient, especially those of Japan, have also played a major part in the shaping of his life and music.

If that Eastern spiritual influence on Ibrahim’s work as an internationally renowned composer and musician could be summed up today in one word, it would be senzo 先祖— the Japanese word for ancestors, ancient ones. His more recent musical recordings pay open respect to the influence and inspiration that he has found in what he calls the “Japan cosmology” or the Japanese metaphysical view of the universe. In 2008 he released Senzo, an album of solo piano work recorded in Germany, where he now lives: “I dedicate Senzo to all my teachers — ancestral and present,” he writes in the recording’s liner notes. In 2013 he released a quartet recording with a Japanese title and concept, Mukashi 昔 — Once Upon a Time. As a composer and lyricist, his back catalog of more than 50 studio and live recordings is replete with such musical compositions acknowledging the rich traditions of both his African ancestry and Japanese spirituality.

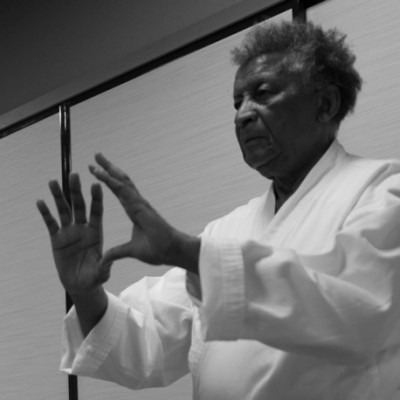

Beyond that, Ibrahim holds a 10th-degree rank of black belt in a specialized, ancient style of karate dating back about a thousand years, called Yashin, a style not commonly learned by Japanese karate students in Japan. Ibrahim has been studying for decades under Yukio Tonegawa, a karate master originally from Aomori Prefecture who spent nine years in Copenhagen, Denmark during the 1960s and 1970s teaching his family line’s budo (martial arts) practices to Scandinavian students. Tonegawa today heads the Kodosoku-kai martial arts organization in Tokyo. Ibrahim, as a master-level sodenke (successor, inheritor) certified by Tonegawa, is qualified to teach that ancient form of Japanese budo and pass the tradition on to others. Ibrahim likes to humorously recount the story of his humble ascension to becoming a martial arts master: “I’ve studied traditional budo in Japan for fifty years and a few years ago my teacher gave me a certificate to teach. I asked my teacher, ‘Why do you give me this? Because I don’t know anything.’ And he said, ‘That’s why I give it to you, because I too don’t know anything.’”*{1}

Abdullah Ibrahim shared his thoughts on this and other topics recently in Kyoto, where the veteran musician performed two nights at Kamigamo Shrine and then made a rare appearance at another master-class event of sorts and was feted by younger Japanese musicians.

Let’s start with budo. Most people the world over know you as a master musician, but they may not know you are also a master of Japanese martial arts. How did budo begin in your life?

I think it’s the story of most of the people that I know that have pursued this path. I was a very sickly child, so I tried to find something to develop myself physically. I used to run 800 meters, 1,500 meters, 3,000 meters. This gave me a good insight into myself physically, mentally, where I was. And also, there’s what they call the “runner’s high”: You run, and you get to a point where you feel like you can run all day. So, my great-grandfather and -grandmother’s people all come from that [running tradition], from the San people or “Bushmen” people [of southern Africa]. So, I used to run. But then, when I started going on the road [to perform], I couldn’t find time and space to run. So, this is what attracted me to budo.

I started with Eastern philosophy and religion, the Bhagavad Gita, all the European philosophers — I studied all of them. But the thing that drew me in was the Japan cosmology. I found that it resonates with our [African] concepts, especially this reverence for nature. Then I found my karate teacher, Tonegawa-sensei. I’ve been studying with him now for 50 years.

I met him in Europe [in 1969]. I was in Copenhagen; he was studying design. I heard that he was teaching at a little dojo there, so I went to introduce myself. I’ve been studying with him since that time. When he came back to Japan, I used to come to Japan and study with him.

What parallels or common points do you see spiritually between Japanese budo and being a musician on stage, playing in the moment?

Tonegawa-sensei says, “When you make a mistake, make a good mistake.” Because there’s no such thing as a mistake. For me, the application of the concepts of budo is the same as we play in jazz music. Musashi [Miyamoto, early 17th-century Japanese samurai-philosopher] said, “Under a sword lifted high, there’s hell to make you tremble.” It’s basically the same principles when you play jazz music. Because when you play jazz music, improvisation is scary. You’re going into a place that you’ve never been before. And it’s terrifying [laughs]. But you prepare yourself for any occasion. …You practice, and when you get used to choices, you can apply it. So, it gives you that confidence to keep going. It’s the same thing when we play jazz music.

You take a song, you practice it for 20 years, turn it around and play it in all the keys with all the possibilities — what’s the harmony, what’s the rhythm, what’s the melody? — and then when you play the song [improvised], you have this confidence. It’s the same with budo. But it’s not for fighting. It’s just to prepare yourself for when you get in a situation where you’ve never been before: How do you humanly resolve that at that point in time?

Is it fair enough to say that Tonegawa-sensei has been as much of an influence on you spiritually as American jazz masters like Thelonius Monk or Duke Ellington or [South African jazz legend] Kippie Moeketsi were?

My teachers all are younger than me [laughs]. It’s the just the sense of whatever it is that you’re doing or pursuing, it must be practical. It’s supposed to be for practicing. When you float [among] all these grand ideas, you have to have your feet planted. And that’s what I find with the masters like Tonegawa-sensei, with Duke, with Monk, with Miles [Davis], all of them. It’s grounded. They once asked Duke Ellington, “Duke, how do you manage to keep all these great musicians with you for all these years — Johnny Hodges, Russell Procope, Cat Anderson? How do you keep these people?” And Duke said, “I found a gimmick: I give them money.” [laughs]

It works every time.

So, this is what we learn from the masters — something practical. When you have these grand ideas floating around 24/7, you have to be grounded. And this is the principle of budo, the principle of jazz music.

Can you tell us a bit more about your relationship with Tonegawa-sensei? Perhaps in the beginning it was between a master and student, but now between a master and master.

You know, this concept of a student and a master is somehow a strange concept, that you have to go somewhere to get your learning. For us, when you are ready, that person will appear. I didn’t know this person was the master. And then, when I was ready, he said to me, “I’ve been waiting for you.” So, it’s another kind of relationship. It’s not something that you want to go to somebody and choose: “I’ll go to this one to study with or to learn from.” When you are ready, that person comes to us. It’s totally organic. And I think in any tradition, there’s this relationship between so-called student and master, student and mentor. It’s always when you are ready. When you are ready as a student, you will be introduced to the master and the kind of relationships that you have.

[About his level in karate] They call it “master,” but this is something personal. It’s a personal achievement. You don’t go around telling people that “I’m 10th dan [degree]” or so. It’s another consequence, whatever it is: a learning experience, your relationship with somebody else. It’s your personal achievement or non-achievement. You always have to be striving. Practicing — instrument practicing, budo practicing — is 95 percent. Performance is five percent.

Did your music turn toward the East when you embraced Islam as a religion back in the late 1960s or was it already moving in that way?

As somebody once said, “The only people who do not change are prophets and fools.” They change. Everything is in change. The questions that one asks when you’re young, you’re always asking but you can’t get answers because the people that you are asking also did not have that process. There’s no continuity in relationships at the individual level, at the social level. So, it sort of gives you the idea: “Wait a minute — this is not correct. The answer that you’re giving me is not correct.” Then you find out what is the answer. You’re always striving, asking questions about yourself. You just don’t accept things. Because whatever it is, it belongs to me. Not what makes other people comfortable, but how does it affect me and my life personally?

I grew up in the church, and this is part of the spirituality that we grow up with: our parents, our grandparents, our great-grandparents. Then when you grow up, you’re exposed to other concepts, and you find the concept that answers your questions — that makes you feel humane, makes you feel comfortable with it. Because there’s only one God. Many michi, many roads, but only one [God]. I think Rumi said it very beautifully: “There’s only one sound. Everything else is echo.” So, we don’t strive for the echo; we strive for that sound.

****

The day after Ibrahim’s two unforgettable night concerts at Kamigamo Shrine, he is set to host an informal two-hour-long “open class” in an upscale neighborhood of Kyoto, not far from the famous Yoshida Sanso ryokan, a favored retreat of Japan’s imperial family in olden times. In a private piano recital hall seating an audience of only 60, what was intended to be a kind of master class featuring Ibrahim becomes an impromptu jam session as he invites some local Japanese musicians up to the small stage right at the start. The musicians, a generation or two younger than him, open with the saxophone lines to “The Wedding,” a popular ballad of Ibrahim’s, and he laughs. It is a song in his repertoire that seems to have universal appeal and a healing quality all its own.*{2} The Japanese musicians segue into the quick pace of “African Marketplace,” another of Ibrahim’s signature songs that has traveled far over the years among his many fans in various countries.

Ibrahim fields questions from members of the Kyoto audience about his life and music, and being the natural storyteller he is, offers a teaching on piano about how to resolve conflicts, using the song “Seven Steps to Heaven” by jazz trumpeter Miles Davis as an example: In music as in life, no matter how far out there on a limb you find yourself, you can always “come home” again within a few notes or a few actions. There are no such things as mistakes, he says, only solutions. He closes the class by inviting the Japanese musicians back up to the stage, where they finish with an improvised rendition of “Tintinyana,” one of Ibrahim’s older Africa-themed tunes. The maestro himself looks on, swaying, raising his fists in rhythm, and obviously enjoying the tribute. It is clear that while Ibrahim has been intensely studying Japanese culture and ancient traditions over the years, a younger generation of Japanese musicians have come of age studying his musical traditions too.

****

There are many young people today who are inspired by you, like you were inspired by the greats in your day — Monk, Ellington and all the rest. How do you feel about the music being made today and the way it’s being presented? Are we getting that sound? Or is all the marketing and digital technology and video getting in the way of reaching people?

You know, [American jazz pianist] Art Tatum — I can never reach that level, whew, it’s unbelievable — Art Tatum wrote a song for piano called “Elegie.” It’s a very difficult piano piece. So, [educator/pianist] Billy Taylor once told us that he and Art Tatum were in concert and after hours they went to this small club. There was a young kid playing there and he came over and said, “Mr. Tatum, so glad to meet you, I’m so inspired by you. I would like to play one of your songs, ‘Elegie.’” So, he went up and says, “I’m playing ‘Elegie.’” Billy Taylor said Art Tatum didn’t even listen, he was drinking [laughs]. Then he said, “Art, he’s playing your song. They’re playing your music.” And Art Tatum says, “He knows what I played. He doesn’t know why I played it.”

So, when you say “young musicians,” it’s not a question of what, but why. We’re so concerned with “What did this one play?” But why did he play it? This is something personal that you would never know. Why did somebody do this? We just don’t have enough time [in a day] to practice is what the problem is.

Notes & quotes — Abdullah Ibrahim on the Japan cosmology:

*{1} All About Jazz, “Abdullah Ibrahim: The Sound of the Universe” (2019).

*{2} “I have this song called ‘The Wedding’ and people come up to us, couples come up to us, at concerts and say they used that recording for their wedding reception. We were playing a festival in London and the promoter told us that there was a man who would like to meet us. Apparently, he’d been waiting almost the whole day and we met with him and he said that he drove five hours to come to the concert. He’s a medical doctor and he deals with children in coma. And this young girl, she was comatose for a few years and nothing helped. Then one day he put on the earphones and played ‘The Wedding’ for her and she came out of her coma. In Tokyo, one of our friends gave us this message, that this lady had contacted them. She went for major surgery and she asked the doctors if they could play ‘The Wedding’ as she goes into surgery. So, these are the kinds of reactions that we get from people and I think it’s an organic way of people expressing what they believe through music. And this is gratifying in the sense that I don’t know how it works. Maybe I don’t want to know. We just play the music.” (All About Jazz, 2019)

—“To let that music or whatever it is flow through you is like a samurai. It’s like a state of Zen. You yourself have to be completely composed. This is what composition means — that you must be composed so that that message can flow through. When it comes to you, when it flows through you, it even serves as a means of purification. And this is the high. It’s a state of high, a state of spiritual high. And when musicians have to deal with this industrial society, with iron and steel, it’s very hard. The physical high: If you want to get high, you jump; you must come down. The spiritual high can only be obtained through spiritual means. Now, in order to maintain that constant high, the only way out to maintain your sanity and your health is that you must be completely composed and let yourself become the vessel of the Almighty.” (from the film A Brother with Perfect Timing, 1987)

“Miyamoto Musashi said, ‘Under the sword lifted high, there is hell to make you tremble. But go ahead anyway and you will find bliss.’ You’ll find that peace and repose. This is the same as the music. They call it jazz, this music we play. It’s samurai! And that’s why you find very few people who want to get involved in this music because it means putting your life on the line. You are given a set of circumstances, which is your song: You learn the head or the melody — now you have to improvise. Now, when you hit that first note that you play, you are putting your life on the line.” (A Brother with Perfect Timing, 1987)

–“Karate has nothing to do with fighting. It’s about catching your energy and using it in your life and work.” (Learn and Teach, 1990)

—“You know the Zen masters’ saying about the iron flute? It is actually the highest developed instrument. It is solid iron, with no holes. If you are able to play that, you are a master. Our music is related to Zen, that’s why it is so popular in Japan. I study martial arts, I have the fifth-degree black belt. The concept of martial arts is identical to the concept behind jazz. [Former South African president] Nelson Mandela is a martial artist, a boxer. He understands the art of war. Not the art of war that is about fighting and killing people, but the art of war with the self. The Prophet [Muhammad], peace be upon him, said that after the small jihad [holy war] comes the big jihad, which is the battle with the self. This is what our music is also about.” (Crownpropeller’s Blog, 1995)

—“Martial arts is possibly a connotation in error. The Japanese term and concept is budo — the art of not fighting! The inherent principle in budo is the universal acceptance of the majesty and awe of nature — sky, trees, river, mountains, sea, birds — and how through the practice of budo we can attain and maintain this harmony.” (JHB Live, 2014)

—“The ultimate aim is reflected by the Japanese term mu-shin, which literally means ‘no mind’. So, when I studied with my martial arts teacher in Japan, it was on how to evolve what’s in oneself. When I practiced, my teacher said I [was] thinking too much. It’s the same in music, about having no mind. One has to live in the very moment, which has no past, no future. That moment is about listening to our heartbeats, how we breathe, and in music focusing on a single note. I work from the principle that I want to feel every person in the audience, and what connects us is focusing on that precise moment. It is easily lost. Once I strike a note, there is nothing I can do about it. After all these years I can say that I’m beginning to understand how to play a single note. And one does it without expecting anything in return. It is a principle of living, of giving unconditionally.” (Adelaide Review, 2015)

“In budo, martial arts, the power is in the belly. That is the seat of emotion, not the heart. That’s why we talk about ‘gut’ feeling. My martial arts teacher once told me, ‘I don’t like jazz or classical music, but I like how you play because it sounds clean’. By that, he meant ‘not intending to show off technique’. The tendency in jazz improvisation is to go for what impresses, but as [saxophonist] John Coltrane said, the principle in performing should be that each night feels like the very last night you are on stage.” (Adelaide Review, 2015)

—“We confuse music with sound. Our concern and investigation and study is with sound. The illustrious poet Rumi said, ‘There’s only one sound. Everything else is echo.’ Find that first initial sound within ourselves. As musicians, for me at least, it’s discovering that the sound that resonates within us and resonates with the universe, some call it gravitational waves. In Japan, the word is hado. But it’s principally the same formula or essence that pervades the whole universe. So, it’s sound that’s then translated into what we call music.” (All About Jazz, 2019)

[About performing his older musical works in recent times] “I’ve been studying budo and there is this idea of asymmetry. Nothing is symmetrical because if something is symmetrical, there’s no reason to engage. Because it’s complete, right? But if it’s asymmetrical, then the listener or audience, the viewer is drawn into it. And this is the principle of asymmetry. And so, revisiting these compositions is finding that asymmetry that is embedded in there, that’s really embedded in how we live and the principle of the universe, which is yin-yang, plus-minus or whatever we call it.” (All About Jazz, 2019)

Brian Covert is an independent journalist, author and educator based in western Japan. He has worked for United Press International (UPI) news service in Japan, as a staff reporter and editor for English-language daily newspapers in Japan, and as a contributor to Japanese and overseas newspapers and magazines. He currently teaches journalism at Doshisha University in Kyoto.

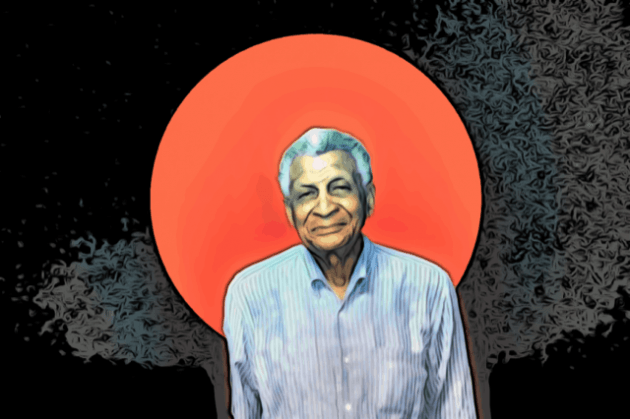

Header photo: Abdullah Ibrahim by Marina Umari

Photos by Lush Life Family, and courtesy of Abdullah Ibrahim. Digital graphic by Brian Covert.