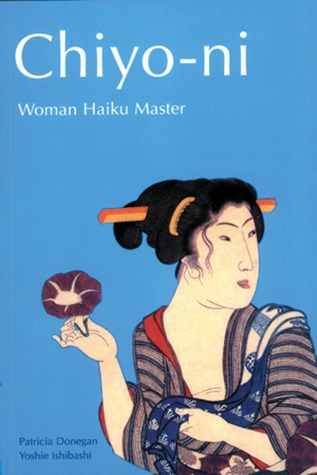

Chiyo-ni: Woman Haiku Master, trans with commentary by Patricia Donegan and Yoshie Ishibashi. Tokyo: Tuttle, 1998. 280 pp.

On the brink of the 21st century, so many literary works by major figures in Japan have yet to be translated into English. The majority of translations, especially in the realm of poetry, are limited usually to sweeping surveys of hundreds or even thousands of years of literary history. Although one should be satisfied to read any translated offerings, one is rarely allowed an in-depth look at any particular writer.

In addition, those few translations that do exist of particular haiku poets have focused on male poets such as Basho, Shiki, and Issa. For these reasons alone, readers should welcome the recent translation of the work of a premiere Japanese woman haiku poet, Kaga-no-Chiyo, by co-translators Patricia Donegan and Yoshie Ishibashi. Relatively unknown and overlooked by scholars outside of Japan, Kaga-no-Chiyo (1703-1775), a poet artist-calligrapher, perhaps with this book can join in familiarity the likes of Shikibu Murasaki, Ono no Komachi and Yosano Akiko.

The book—Chiyo-ni: Woman Haiku Master —held in both hands, feels generous. Indeed, the design allows for one haiku per page, and each poem is written in three ways: in romanized Japanese, in English, and in its original Japanese. Too often we are given only the English translation of Japanese poetry, which does not allow us to “hear” or ‘see’ the poem in its true state. Even those who have never heard or read a word of Japanese can appreciate the aesthetics of Including the original language; while those who read some Japanese will find the inclusion a blessed relief.

In addition to over one hundred translated poems, Donegan and Ishibashi also cite each haiku’s kigo or seasonal word, and they provide contextual notes for many of the poems. Chiyo-ni’s skills as a calligrapher and painter are also shown with numerous examples of her haiga (haiku painting). Other artists’ depictions of the poet, such as Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s beautiful ukiyoe woodblock prints, are included, in fact, with the book’s illustrations, haiku, haibun (haiku prose) and renga sequence (linked collaborative verse), map of Kagano-Chiyo’s Edo-period Japan, glossary, and bibliography, some readers might find themselves almost overwhelmed by the extensive scholarly research contained in this book.

The poems themselves vary in power. Some haiku strike the heart instantly, with flashes of color, while others are subdued, muted, or left in the remote regions of the mind. For instance, consider the contrast of tones in the following two translated poems:

how terrifying

her rouged fingers

against the white chrysanthemum

shirogiku ya / beni saita te no / osoroshiki

the shimmering haze

above

the wet stone

kagero ya / hashite wa nururu / ishi no ue

Poems like these demonstrate the tonal range of Chiyo-ni. Her poems often succeed in capturing the intricate variation between moment and perception. As Donegan notes, haiku is a poetry essentially touted as “’objective,” and for this reason haiku is deemed more masculine than the supposedly feminine or “subjective* form of tanka. She suggests that one reason Chiyo-ni lacks the admiration of male scholars might be due to her powerfully subjective poems. Yet. if we look at haiku, especially that of poets such as Issa, Kaga-no-Chiyo and even Basho himself, we can sense that the supposed objectivity of haiku often gives way to a deeper connection, an empathy with nature.

In the book’s preface and in the separate essays on the poet’s life and haiku, readers may sense that this translation work, for Donegan especially, has been a labor not only of love, but also of retribution for the dismissal of this woman poet by previous scholars. Also, the translators allow for readings that sometimes find a rebellious, socially aware woman in Chiyo-ni. Usually these ‘womanist’ readings of a poem are given along with the more predictable, traditional reading. For instance, the poem below is included within another poem’s notes:

just for today / using men / for rice-planting

kyo bakari otoko o tsukau taue kana

The translators’ comment on this haiku is as follows:

In the Edo period most of the rice planting was done by women yet sometimes men were asked to help, so me word tsukau meaning to use could just be taken matter-of-factly. on the other hand, the tone of this word could also be seen as bold, unrefined or even feminist.

In the above text, and elsewhere, the translators’ preference for a strong-willed woman in Chiyo-ni becomes apparent. Yet this preference is not necessarily one that the book’s readers must have to enjoy this book.

I personally found the translators’ renderings thought-provoking, even as I wondered whether such bold readings matched the actual intent of its poet, Kaga-no-Chiyo. In truth, it is refreshing to read unconventional translations. Patricia Donegan and Yoshie Ishibashi’s work, hopefully, shall open up a healthy dialogue within the traditionally male-dominated world of Japanese literary scholars both in and outside Japan. If not. then at the very least readers have a rare opportunity to enjoy the haiku of this previously neglected poet.

From issue KJ 39, published 1999.

Rebecca Dosch is a former Kyoto resident; her poem ‘Explain Why’ appeared in KJ 23, our Neighborhoods issue.

Image sourced from Goodreads.