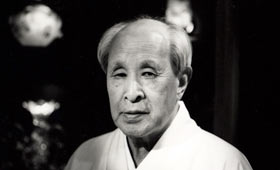

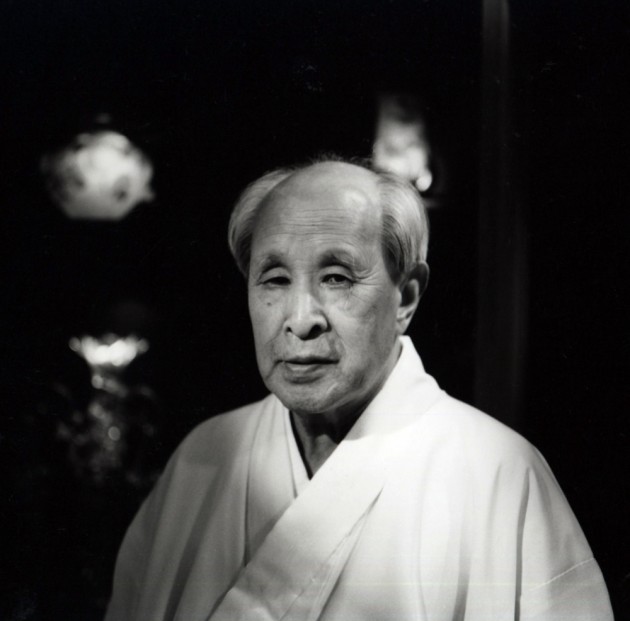

Tucked away on the edge of Kyoto’s Gion district is Ema Shrine (officially known as Yasuikonpira-gu), and tucked within Ema Shrine is “the glass room.” Here, antique and contemporary works of glass art are gracefully illuminated in elegantly-crafted display cases. One enormous bowl, by contemporary American glass artist Dale Chihuly, glows from a showcase beneath a transparent floor of glass. Frothy green tea is served to visitors in 19th century glass bowls from Italy. The keeper of the glass room is the shrine’s former head priest, 76 year-old Torii Hiroyoshi.

About forty years ago when my elder brother died, I was obligated to take over as head priest of this shrine. I had no inclination to become a Shinto priest, but I really had no choice. It was in my family. But I thought being a priest might not be such a bad thing after all, it might give me the freedom to try some things I wanted to do.

I believe the buildings and precincts of a shrine should in some way have cultural “color.” By this I mean each shrine itself should breathe, as if it were actually alive. How this is accomplished depends entirely on the particular interests of the head priest. For me, it was art. When I was in my twenties, there was an art gallery called Azuma in Kyoto that I often went to. I encountered all kinds of fascinating people that met regularly at the Shinshindo coffee house on Imadegawa street. This was a great influence on me. Art, I decided, other and with myself within the context of Shinto.

To make my shrine more colorful, I decided to build the Ema-do [ a museum of votive tablets (ema) dating from the Edo Period to the present on the shrine grounds]. There are many interesting ema. But like ukiyo-e, they were ending up in foreign collections. No museum in Japan was collecting them, so I thought building a museum for ema only would be a great thing. Everyone was against this idea, however. Twice a year for ten years I brought my museum plan to the shrine association meetings. And every time it was voted down. But after persisting each year they finally gave in and told to “go ahead, do what you want. But don’t expect any support from us.” I started construction the very next day.

Some rooms in the Ema-do contain works from my art collection. Since I have over 400 pieces, including a Monet and a Rodin, I thought of building another small museum within the shrine precincts. But the cost was prohibitive. I had started collecting glass, and so I decided to make a “glass room” instead. Everyone opposed this plan as well. But I had it built according to my own design. One wall I reserve for the works of my artist friends in Kyoto. I change it each month. People always wonder why such a place exists in a shrine.

Although some glass pieces here are more than a hundred years old, if they are displayed with care are illuminated just so, and are experienced in an atmosphere of harmony, they become new again. It is as if you are seeing them the day they were made. Art cannot be experienced in this manner in the large art museums of today. But here, in this very small space, we can talk to each other — not as lay person to priest — but as friends. An intimacy is created. Through such encounters between art and ourselves, inner change is possible. You can experience a feeling of renewal. Renewal is at the heart of Shintoism. So this room is my expression of what I believe Shintoism to be.

Through various circumstances, people suffer pain…doubt. It often concerns something they cannot express openly. The act of painting a picture or writing their hopes on an ema enables them to begin anew. The glass room serves the same purpose. Your fate begins he day you are born. But each day offers a new beginning. The role of a shrine is to assist people to exorcise their doubt, their suffering. To shake their lives up a bit so they can start over again. This is the path of Shinto, regardless of what age we live in. A shrine that doesn’t accomplish this is quite dead. There are shrines today that sell trinkets and all sorts of things. This is not the true spirit of Shinto.

A few years ago, I saw Shakti [a contemporary Japanese dancer] perform. She was stunning. After the curtains closed, a powerful feeling lingered in my heart. I decided I wanted her to perform at the ceremony where my duties as head priest would be handed down to my son. Everyone, including my son, fiercely opposed my plan of course, but I insisted. So I asked Shakti to create a dance that would tell the story of Emperor Sutoku, the founder of this shrine. A scroll depicting his life story is one of the many cultural treasures stored here. It is said that he loved wisteria and lived with his mistress in the shrine. However, he led a life of great pain. He suffered a long illness. He lost a war and his heart was filled with resentment for many years. In his old age he met a great priest named Saigyo Hoshi. This encounter led Emperor Sutoku to devote his life to the religious path, and his eyes were opened at last. On his deathbed his heart became serene and he departed utterly at peace with life.

Shakti gave a moving performance. Traditional things have no meaning unless they are continually made new. The Ema-do, the glass room and Shakti’s dance are some examples of how I’ve tried to give my shrine “color,” to keep the spirit of Shinto alive in the present.

Yasuikonpira-gu website (Japanese)

The Comb Festival is held Sept 26th. Kyoto Visitors Guide says: “This unique festival is dedicated to offering thanks to women’s combs and hair ornaments. From 13:00, a ceremony is held and then a beautiful procession of women with their hair done in a wide range of styles spanning more than 1,300 years and wearing clothing from those periods will walk through the surrounding area.”