With illustrations by Alex Mankiewicz

Friday.

He came in with his earphones still on. He started dancing by the door.

For fuck sake.

“Hello,” I said.

“I think we should break up,” he said.

He kept dancing. He was drunk. He’d gone out with the rest of them after work. The international school in Saigon we both work at finishes early on Fridays. The men usually go to one of the girly bars down on Pasteur Street where the bar girls dress in heels, short skirts, white makeup and red lipstick. The expat men pay them to drink and flirt with them.

I threw a pillow at him but he kept dancing, headphones in, eyes closed. He had the delighted, drunk, stupid look a lot of expat men out here have.

He kept dancing. He made the two-hand-waving universal sign for ‘come dance with me’.

“I’m sober.”

It was quiet. The music gnawed at his ears. The apartment was lit by one free-standing lamp and by the glow of the city 26 floors below. His shoes squeaked on the tile floor of the kitchen as he danced. Motorbike beeps floated up from the traffic below like lost balloons. He danced. The air conditioner blew like a coastal storm, deep and rolling but nowhere near as refreshing. He danced. I listened to the noise of the hot, polluted Saigon air being turned colder and less polluted. He took one earphone out.

“Come and dance babe,” he said.

I went over to look out the window at the traffic. Down on the streets, motorbikes wriggled free of stop lights like fish through a net. Saigon looked cleaner and more modern lit up at night. Red lights blinked on the tops of the other tall buildings, warning the planes away. Yellow squares of advent calendar windows shone from the apartment blocks. Searchlights flailed from the rooftop bars where the expats and the rich Vietnamese and the expats’ Vietnamese girlfriends were drinking cocktails which cost the average daily wage. Our work crowd usually had a table booked in one of those places. They would have already started to arrive and complain about the service.

For expats in Saigon, the Vietnamese are there to serve in bars and restaurants, to clean our apartments, to drive us around, to cook and deliver our food, to politely smile through our petty complaints, to work the same jobs as us for a tenth of the wages, to pay inflated prices to be taught English by hungover native speakers, to mind our children and massage our bodies, to do our nails, to guard our apartment buildings and, if they’re men, to be mocked for their lack of masculinity by white women and, if they’re women, to be prized for their skinny, exotic, submissive femininity by white men.

He kept dancing. He danced over beside me.

“I think we should break up. Did I already say that?”, he said.

I pulled one of his earphones out.

“Stop dancing.”

“Chill babe,” he said.

Prick.

He danced down the hall and into our room. He sprayed himself with deodorant without turning on the light.

“I’m going back out. Love you,” he said.

He put his earphone back in and danced out the door and down the hall and into the lift. He drunk-motorbiked through the streets of Saigon. The streets of traffic. The streets of broken footpaths. The streets of cockroaches. The streets of rubbish. The streets of rats. The streets of food stalls. The streets of poverty. The streets of wealth. The streets of massage parlours. The streets of brothels. The streets of police. The streets of high-end fashion. The streets of hostels. The streets of five-star hotels. The streets of tailors. The streets of tourists. The streets of soldiers. The streets of plastic chairs. The streets of fish tanks. The streets of Friday night.

Saturday.

He was in bed beside me when I woke up at seven. The sky was bright blue. It was 28 degrees outside. Half of Saigon were already up, exercising in the parks and shopping at street markets and sweeping their front steps and fixing their motorbikes and walking to their English classes and drinking breakfast soups and fishing in dirty rivers and drinking coffee and hosing down their restaurants and washing their boss’ cars and swiping on tinder and posing for photographs and getting buses to the beach. They were up to get everything done before the screaming midday sun turned the city slow and sticky.

I poked him awake. He got up and vomited into the toilet. I made a big show of making no comment. To fortify my position on the moral high ground, I went out into the morning heat to get him a drink. Out into the heat and the beeping. Motorbikes in too much of a hurry for the road beeped past me along the footpath. Expensive cars beeped their way through the slow, rolling, beeping traffic with their passengers in the back seats, protected from the sun and the dirt by tinted windows.

It was January. The middle of the dry season. The storm drains were parched and full of rubbish. The dirty air stuck to me like a cobweb. I was shiny with polluted sweat as I bought bread and a smoothie for him at the French bakery. I went back down the street through the beeping and up the lift and down the hall and through the kitchen and into our room. He was asleep. I slammed the door.

“Oh, sorry.”

Haha.

“Happy birthday Matt.”

The heat from outside crashed into the air-conditioned cool like the beginning of a thunderstorm.

“Thanks,” he said.

He closed his eyes and tightened further into the foetal position.

“Do you remember breaking up with me last night?”

“Sinéad, listen.”

Still can’t say my name right.

“I’m listening.”

“Can we do this later?”

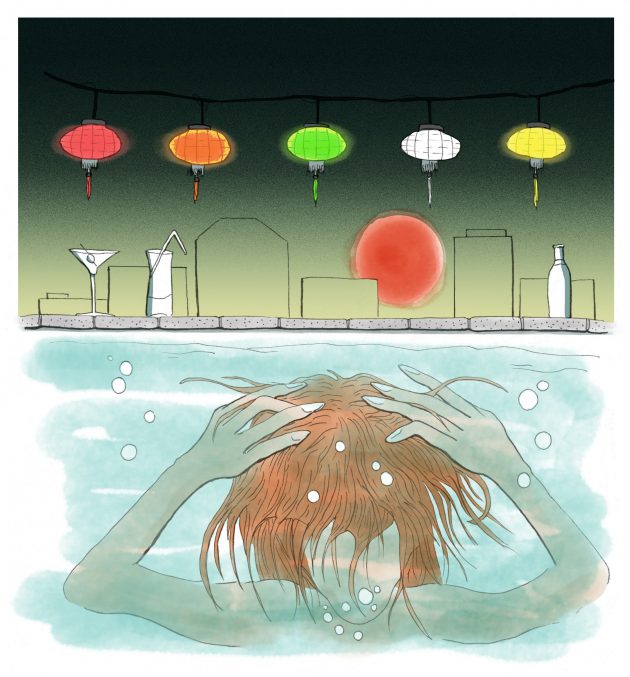

People started arriving for his birthday party in the early afternoon. Our building’s rooftop pool had been done up with bunting, birthday decorations, electric lanterns and pictures of Matt. He’d paid a Vietnamese lad two dollars to do it. We had coolers full of beer and wine. There was a cocktail bar in the shade with a Vietnamese barman being paid a dollar an hour. Inflatable beds and rings floated on the light-blue water, being inched around by the breath of a breeze you get on the 40th floor. A Vietnamese DJ being paid ten dollars for the day and night had set up his decks by the stairs. He played hip-hop and funk from the Google Doc of songs Matt and his friends had spent the week in work emailing each other about.

I sat with a friend of mine. We were in our bikinis, dangling our legs into the sunny water and drinking white wine. The sun boiled my head like a fever. My skin looked browner through my sunglasses. I told her about the night before and how he kept dancing. At one point he came over and put his hands on my shoulders and kissed my cheek with his beery mouth.

Once he told me he’d slept with 37 Vietnamese girls in his first 6 months here. The lads out here keep count like that. Another lad, who you wouldn’t give a second look if you saw him out at home, was going through the alphabet, as he calls it, dating Vietnamese girls in order of their names. He was on M.

Living in Saigon is a bit like being in college. Everyone knows everyone. Everyone knows who’s sleeping with who and who wasn’t invited to who’s birthday party and everyone is available to spend lots of time discussing it. It’s a city with a population of nine million but for most of the expats drinking there under the afternoon sun, it’s a small town of about 10,000 expats. 10,000 mainly young expats with too much free time, too much disposable income and not enough adult supervision.

More people arrived. They came up the lift and up the stairs and dropped their drinks into the coolers and said “woo” and “Hiii” and went over to hug or high-five the 38-year-old birthday boy. By two the pool was full. People dried off on the hot tiles or sunbathed on the beds or drank under the shade of the umbrellas. There were a good few there from the school we work at, a few of their Vietnamese girlfriends looking incredibly thin and beautiful as usual, four or five American girls in string bikinis with tattoos on their thighs and their hair dyed an unusual colour, a group of French lads, staying close together, eyeing the Vietnamese girls and ignoring the rest of us, three backpackers who someone had met out the night before and invited, there were two French girls, a group of Canadians from the Canadian school, a Vietnamese-American who worked for the UN, a bunch of lads from the Saigon Gaels, my countrymen, drinking cans in the shade, exaggerating their accents and generally acting the paddy.

If you saw the pictures online you’d see cocktails sweating on a wet poolside, and the blue sky, and the hot girls up to their narrow waists in the blue water looking out over the sun cooked buildings. You’d see men in shorts flexing their muscles to high-five or cheers or drink. You’d see sunglasses, tans, bikinis, flower-crowns, six-packs, thigh gaps and white teeth. In one of the many drone videos, you’d see us all together looking up from the sparkling rectangle of the pool. Around us you’d see the other buildings and the other pools on top of the other buildings and you’d see the miniature city traffic rolling along the melting streets. You’d see the young and the beautiful. You’d see the easy, sunlit life of the expat in a developing, unequal country. It’d make you sick if you didn’t know that outside the frame there were the usual boring conversations and complaints.

Every ten or twenty minutes the sun and the noise would get too much for me and I’d dive into the pool with a whoosh of bubbles, into the silence and the cold, into the blue water with its wrinkles of white sunlight. I dipped in and out all afternoon and listened to their nonsense. I listened later as I dried off and the ball of a red sun rolled along in the gaps between the skyscrapers. I listened to them as it got dark and they stood around watching the light-show of the city at night.

They talked about: the Trump presidency; climate change; their maids and whether their maids were stealing from them; the places they had travelled and would travel; their ideas for apps; the pay at Saigon’s other international schools; deworming pills; Anthony Bourdain; Tinder; plastic pollution; the steps required to become a certified yoga teacher; the attractiveness and easy availability of Vietnamese women; the unattractiveness and easy availability of Vietnamese men; the crimes of American foreign policy; female hair loss; the anti-straw movement; Brexit and the dangers of democracy; the novel ‘Shantaram’; David Attenborough; polyamory; the weakness of the pound; problem tenants in the houses they owned at home; the #metoo movement; veganism and the ‘Cowspiracy’ documentary; the littering habits of Vietnamese people; the low salaries of our Vietnamese co-workers; the laziness of our Vietnamese co-workers; the politics of the word ‘slut’; TED Talks; ‘Black Mirror’ and its relationship to real life events present and future; drone photography; the merits of various long haul airlines; the natural hair movement; the undeserving poor; universal basic income; Saigon’s nail salons; Elon Musk; Russian interference in the west; milk chocolate; royal weddings; cheese.

On and on they went, through the sunset and into the night where the lights of the buildings around us flashed in multi-coloured patterns and the traffic pushed along below. We smoked and drank, and literally and figuratively looked down on the rest of Saigon. Matt was hugging everyone. He is a hugger, which is to say, a pest. We’d hardly spoken all day, but it was getting to that stage of the night when the management of the school started to arrive (male headteachers in cotton shirts and beige slacks, female deputy heads in flowery summer dresses) and he wanted to make a good impression. He came over and hugged me. We stood elbow to sweaty elbow and got ready to listen to the management bullshit.

The other people we work with tried to sober up. They pulled their going out clothes over their tanned, damp skin and walked around—fully clothed and still full of shite—looking for someone in management to impress. I was dreading the chat with the headteacher and dreading the birthday song too because I hate the song and people would be expecting me to kiss him at the end. The whole idea of it made me feel sick.

One of the Vietnamese people Matt hired plugged in the oval lanterns and they lit up—two red, two orange, two green, two white, two yellow, two brown—in a square around the dark-blue of the empty pool. A Vietnamese girl arrived and hugged Matt.

Fuck off.

“Tam says hi,” she said to him.

You know when you just know? Well, I knew. The way he said.

“Tam…yeah…yeah Tam.”

With his voice going up and down, pretending to think about it.

Before I could properly twist that knife, we had the headteacher over. He had the boiled, leathery, moisture-less look of an English man who’d been in the colonies for too long. He went on about the family atmosphere of the school. We nodded to every second or third word. He’s so full of shite that if I saw him sleeping I’d assume he was pretending, that he was lying there with his eyes closed to demonstrate the importance of sleep and to show how easily he could do it.

“We have that…family atmosphere,” he said, bending his knees and raising his hands for emphasis.

“Yeah, it’s great.” I said.

“It’s part of that added value for us.” Matt said, meaning me and him.

The headteacher’s wife was there too, embarrassingly drunk already. He usually prefers one of his Vietnamese girlfriends, or for a special occasion, a few Vietnamese prostitutes. It’s a bit of a right of passage, for the male teachers, to see him out in a brothel or a girly bar or a massage parlour, and agree, nod and a wink, to say nothing.

“It helps us provide that provision for growth mindset as our learners progress onwards on their journey through the school and out into life.” He said.

“Yeah, it’s great.” I said.

Someone turned off the lanterns and the lights that lit up the pool. In the half-dark the headteacher winked at me. He went away and carried the cake back towards us. The orange candlelight bounced on his lizard face. The crowd made a half-circle around me and Matt. They sang ‘Happy Birthday’ and did too many “hip hip, hoorays” as their idea of a joke. Lights came on in the windows of the buildings around us. I wished I was single and alone and walking down below with the high-heels and the motorbikes and the life of the place—the cafes full, the music pumping from the bars, the waitresses handing out menus. I wanted to wrap myself up in the cloak of the city on a Saturday night and disappear.

“Kiss, Kiss, Kiss,” the half-circle shouted.

He leaned in to kiss me but I showed him the cheek and, well drunk by that stage, he kissed my eye and whispered in my ear.

“I fucking hate you.”

“Same same.” I said, the only time I’ve ever used that fucking saying.

They cheered and cut the cake up and passed it around. They ate the cake. The DJ started playing again. The lanterns and the pool lights were turned back on. They talked about the cake and about other cakes they’d had and would like to have again.

We left after and went down the lift and out into the dead heat and into the air-conditioned taxis that always wait at the bottom of our building. We went to the expat nightclub as usual and as usual it was full of the usual people: French artists; TEFL teachers in quarter life crisis; import and export lads talking about the price of shipping containers; white girls who manage sweatshop factories for Adidas and Nike; yoga teachers and other white girls doing their yoga teacher training; journalists; digital nomads; embassy staff; fraudsters; real estate agents; bitcoin miners; white men with their extremely hot Vietnamese girlfriends. All the expats were being rude as usual to the Vietnamese staff who were serving them politely and ignoring the rising fevers of privilege that flare up after so much drinking.

I went home without telling him and drank tea to sober up. It was four o’clock in the morning and nine at night in Ireland. I hoped he wouldn’t come back. I asked myself, what the fuck am I doing here? Which, apart from money and cake and the attractiveness/ unattractiveness/ laziness of Vietnamese people, is one of the main expat conversations out here. I drank my tea. The tea I’d brought from home. I drank my tea and watched the lights of the buildings being turned off and the darkness spreading silently across the flat city like spilled blood.

Sunday.

On Facebook he posted the usual message people post on Facebook out here, going on like a celebrity thanking his fans.

Thanks to everyone for an outstanding 38th birthday party. You guys make this city feel like a home from home for me. You really are like a second family. You’re an amazing group of people and I’m lucky to know you all. Can’t forget my first family of course. You made me the person I am today. You were there last night in spirit. Thanks for everything, you’re incredible, I’ll be home soon for all of my presents! Last but not least, thanks to Sinéad for being so great and sharing this crazy, wonderful, frustrating, incredible, magical adventure with me. Here’s to 38 more years of adventuring. Stay classy!

I read the post from bed while he was in the shower. He went out to one of the expat bars where they serve roast dinners on Sundays and show hours of Formula one cars doing laps. I got up and opened his computer.

The joke of it is that, like a lot of people out here, he has no home to go back to. You don’t move to Saigon if your life is going well. He doesn’t even speak to his family. He’s lost touch with his real friends in England. His friends here are temporary friends, friends while it’s convenient, friends until they move to Bangkok or Bahrain or Singapore or South America or back home.

He loves the easy life in Saigon too much to ever leave, the easy money and the easy women. The good weather and the luxury apartments. The pool parties and the holidays. The spending power and the respect for white men. The quality of life, as expats call it. He’ll probably end up like one of those old lads you see out here, going out to dinner with their twenty-year-old Vietnamese girlfriend. Hands and mouth all over her like they’re twenty again themselves. Their false belief that all young women secretly want to ride them proven to be true. Taking advantage of financial desperation. Taking advantage of desperation for visas. Desperate themselves but only for sex and attention, which like everything else here, is much cheaper than at home.

I easily guessed the password for his Facebook. English people are so literal. I was going to log on and add some truth to his post. Enough for it to hurt him but still seem like just a bit of craic. While I was there I looked at his messages. There was the usual birthday rubbish. There were messages from that Tam girl. Hundreds of messages. About five minutes of scrolling, going all the way to September when I moved in with him. She was really good looking, in her pictures anyway and especially in the pictures she sent to him. She was about half my weight for a start. They were messaging this morning.

Tam: Laughing last night thinking of how I attack you sexually 🙊🙊😂😂

Matt: Babe I love it 😍😘

Tam: Still mad about the party 😥🤷🏽♀️

Matt: I know I’m sorry 😣

Tam: You can make it up to me 😁

Matt: I definitely will 🏃♂️🏃♂️🏃♂️

Tam: Three?

Matt: Can’t wait 👊🏿

Tam: 😉

It seemed like so much fun. Affairs always do. It gives your life a proper plot. They were two heroes on a journey, hiding, lying, confiding, overcoming obstacles as they raced towards the goal of each other. I’m sure the sex is great too. It’s easy when you have such a coherent narrative structure.

I smashed his laptop on the floor. The ends dented. The Q and the @ fell off the second time I dropped it. I took his shaving foam and wrote ‘prick’ on the bathroom mirror, took a framed picture of us and broke it by the window, emptied a can of Red Bull over our bed, ripped his favourite shirts, kicked his PlayStation, threw the rest of his cake against the wall, used his putter to smash the standing lamp, tore down the picture of him with Prince Charles. I sat on the bed in our spare room, shaking with relief and panting, full of shame and regret, like after sex. I pulled my suitcase out from under the bed and started packing.

He texted to say he was on the way back so I went up to the roof and the pool. It was quieter up there and even quieter under the cool water. There was still heat left in the dirty air. Enough that I could lie in my wet bikini after and dry without shivering. The pool darkened along with the sky. I could feel myself getting bitten by the mosquitoes who came out as the evening crumpled into night.

He was driving through the streets towards me. The streets of love, the streets of glancing strangers, the streets of dreams, the streets of couples kissing on parked bikes, the streets of dancing, the streets of art. The streets of what Dublin once was to me before I got older and broker and had to leave.

Up there by the lights of the skyscrapers, above the sprawling city, above my massive apartment, above the waiting taxis, above the porters and concierges and the door men and the security guards and the maids and the maintenance men and the receptionists, up there, earning more than I did in Dublin, earning ten times the average Vietnamese salary, up there, by my private pool in my bikini, it was hard to go downstairs and pack. It was hard to go home. Home to the low pay and the long months. Home to the landlords and their tiny rooms. Home to being broke in the damp and the cold. Home to always being exhausted by the effort it takes to survive. Home to the city that forced me out and doesn’t want me back.

I went downstairs and tidied instead. I lied to him about the broken things and he pretended to believe me because he was lying too. I stayed living with him so we could have the nice apartment and the maid and the rooftop pool and the holidays and the savings at the end of the month. I stayed for the view from our apartment. I stayed so I could look down instead of up.

Jeff Walters is an Irish writer based in Bogotá. He has been previously published in The Irish Times, The Moth Magazine, Cassandra Voices, Number Eleven Magazine, Deep Water Literary Journal, Increature Magazine, Cold Coffee Stand and Headstuff Magazine. He won second place in the Fish International Short Story Competition in 2016. He tweets at @pyjamas_black.

Alex Mankiewicz is an Illustrator and artist based in Byron Bay, Australia and Kyoto. Her work ranges from editorial to non-fiction visual narrative for Griffith Review and BAM among others and has been recognised by American illustration, Ledger and Australian/New Zealand Illustration Awards. Her illustrations appear in many a KJ issue, including our latest print issue KJ97 Next Generations.