An Interview with Kyoto Activist Aileen Mioko Smith

Part 1: An Extended version of our Interview with Kyoto Activist Aileen Mioko Smith published in KJ 99: Travel, Revisited, Dec. 2020.

By Jennifer Teeter and Ken Rodgers. All photos courtesy of and subject to copyright by Aileen Mioko Smith.

DESCRIBING HER as a multidimensional character hardly captures the essence of Aileen Mioko Smith, an unrelenting and knowledgeable activist, photographer, mother of her daughter Mana, and now sole caretaker of her elderly yet vibrant mother. Aileen grew up in Tokyo with her Japanese mother and American father, moving to St. Louis in the American Midwest in 1961, at the age of 11. There, “where if something broke, people automatically joked that it was made in Japan,” she was the only Japanese person that many people had ever met.

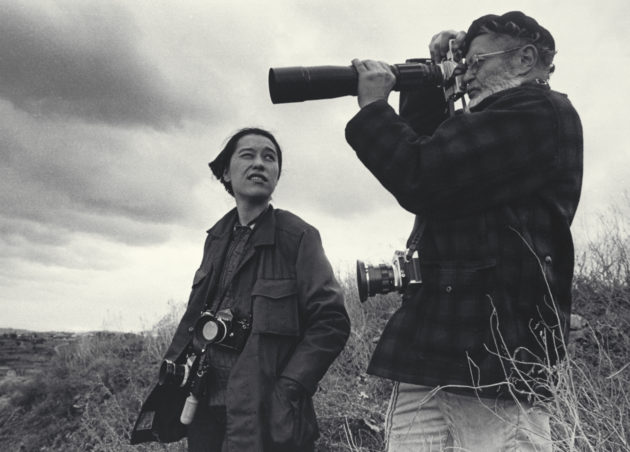

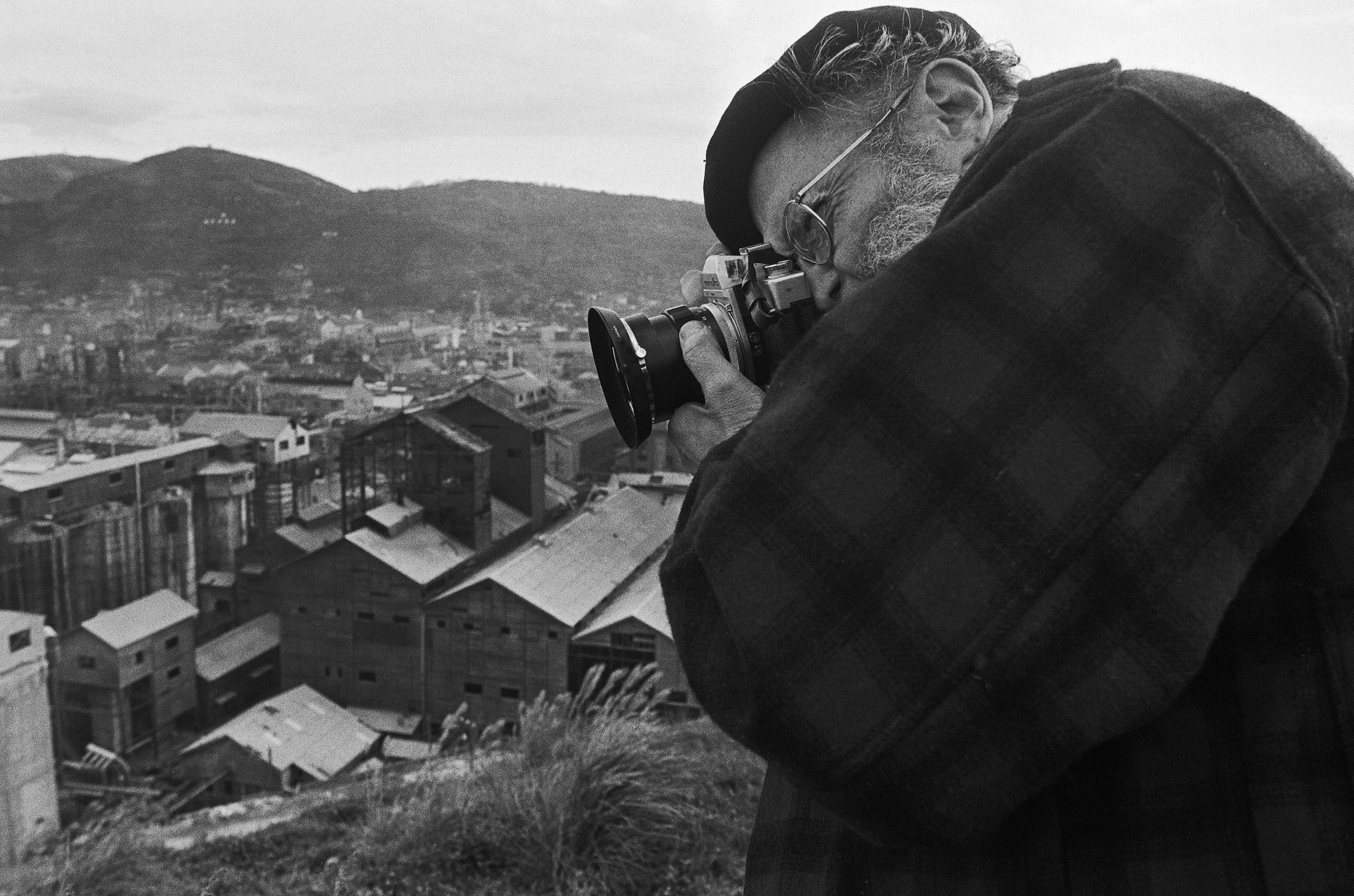

In 1970, after her second year as a student at Stanford, she took up a summer job with the Japanese advertising firm Dentsu and interpreted in photo shoots for a Fuji Film campaign featuring top photographers including W. Eugene Smith, former war photographer and pioneer Life magazine photojournalist. Shortly after this serendipitous encounter, she dropped out of Stanford and moved into his New York loft to assist in preparing for a 600-print retrospective exhibition, titled ‘Let Truth be the Prejudice.’ She was 20; he was 51. “He was so young and I was so old!” she quips. A year later, they took the retrospective to Japan, marrying here on August 28th, 1971.

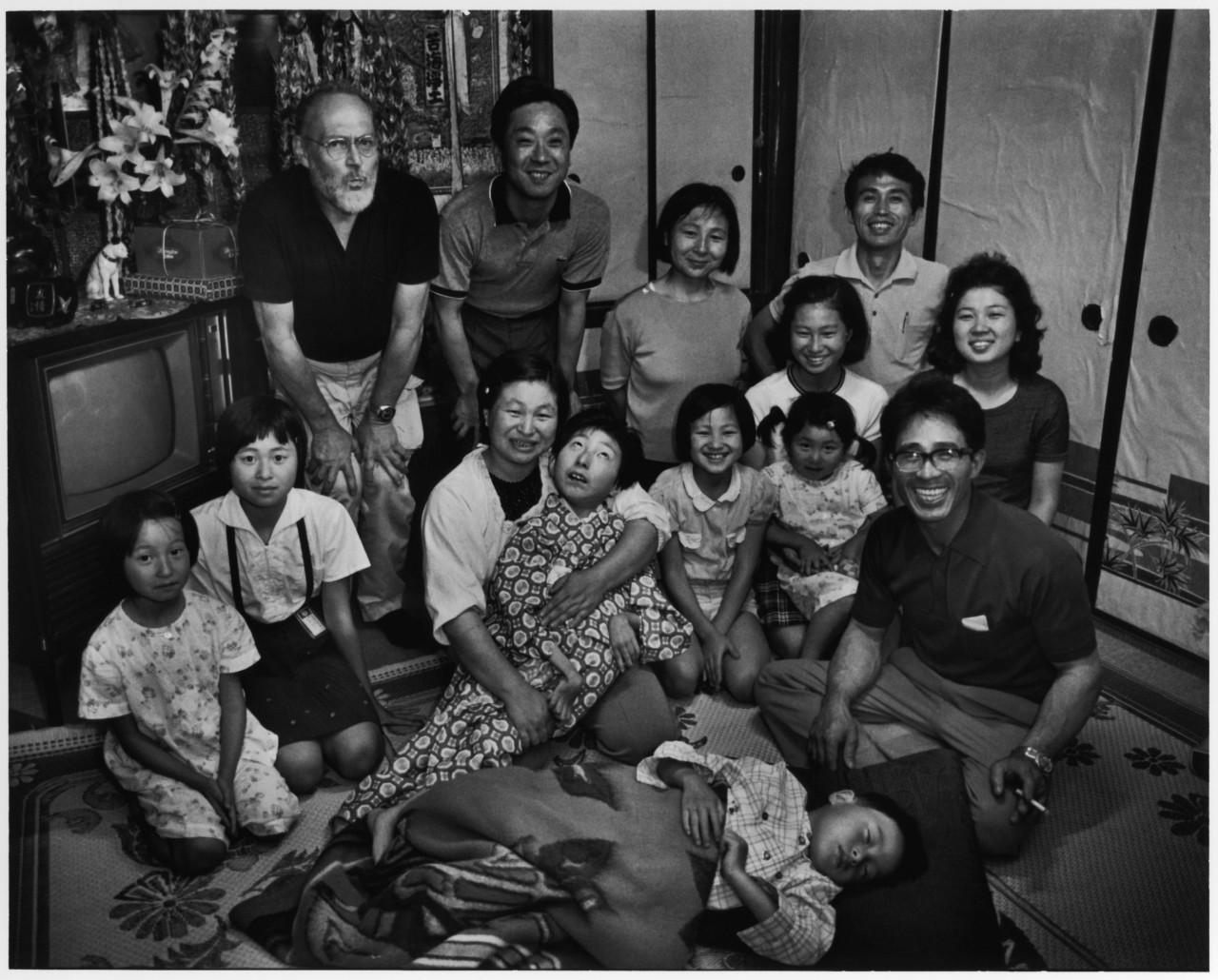

The organizer of that show, Motomura Kazuhiko, suggested that Gene photograph in Minamata, Kumamoto Prefecture, where a public health crisis was playing out (see sidebar). Aileen and Gene rented a house there, thinking they might stay three months. Three months became three years, documenting the lives and the struggles of victims of deadly methylmercury industrial pollution and their families. Publication of their early photo-essay in Life brought Minamata to international attention, and their book, Minamata, co-authored by Aileen and Gene, reached a worldwide audience upon publication in 1975.

A poignantly intimate wide-format integration of hard-hitting reportage and graphic documentary photography, Minamata indicted cynical corporate negligence and malfeasance, and administrative ineptitude. Together, Aileen and Gene recorded local citizens’ heroic resistance through protest and protracted court hearings to a final verdict in their favor. Although Gene and Aileen only appear in the book as witnesses documenting the devastation it has been adapted into a screenplay about their time in Minamata, and filmed as—believe it or not—a Hollywood “true story drama thriller.” Directed by Andrew Levitas, the movie, starring Johnny Depp, was shot in Montenegro, Serbia and Japan , and is scheduled to be released in 2021. As described by Levitas, “This uplifting story of hope, passion, and community reminds us that alone we may be the parts per million, but together we are the millions.”

Sad to say, Gene passed away in 1978. Aileen has continued to support Minamata patients and their families’ ongoing quest for justice, expanding her work to campaign tirelessly against another major public health threat—the nuclear power industry and Japan’s fast breeder reactor and plutonium utilization programs, as discussed in the online version of this interview.

Jen Teeter and Ken Rodgers spoke with Aileen in October 2020 in Kyoto.

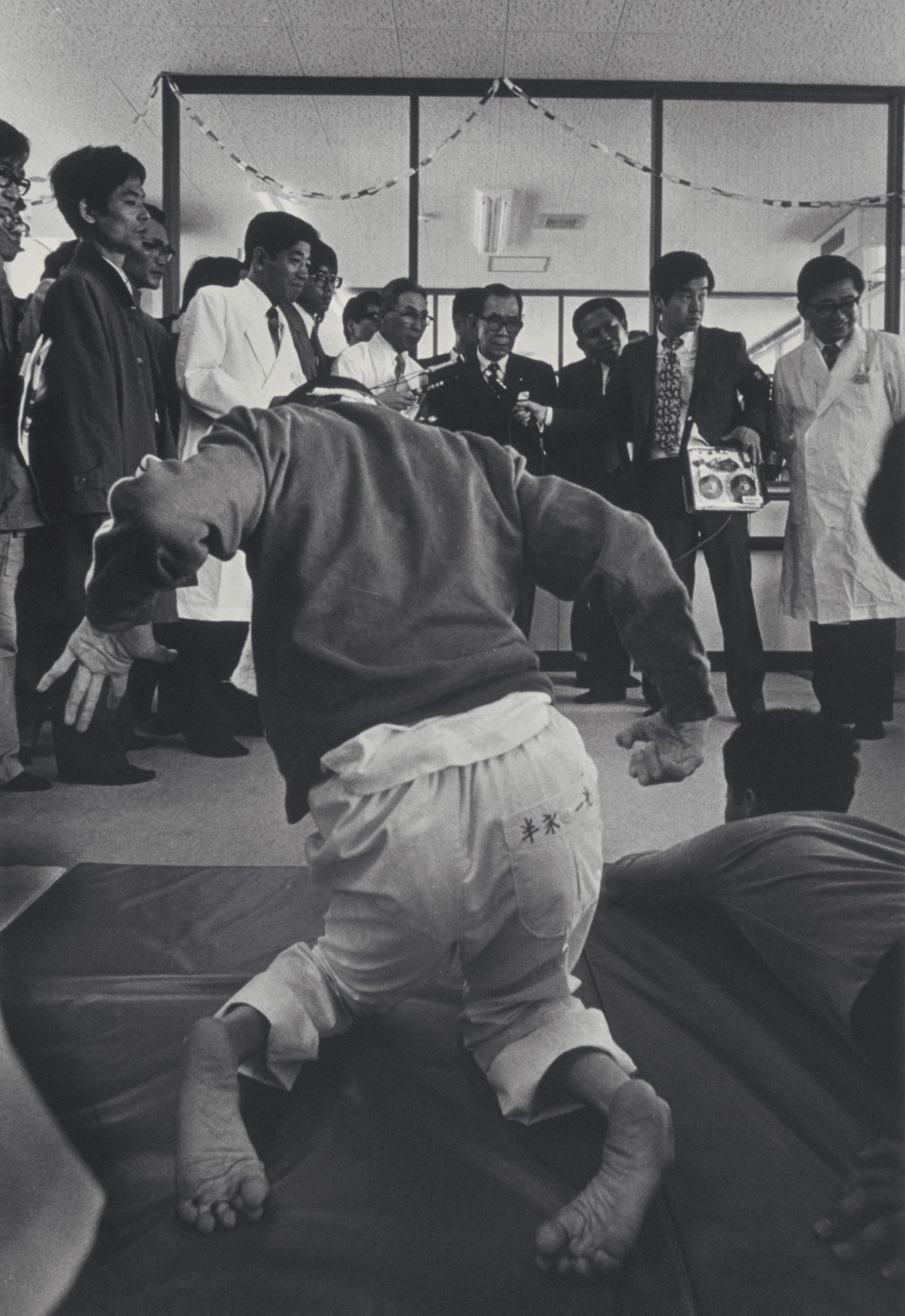

The town of Minamata, in Kumamoto prefecture, Kyushu, is irrevocably linked to ‘Minamata-byo’—Minamata Disease, caused by methylmercury pollution of the Minamata Bay, Minamata River, and the adjacent Shiranui Sea. Starting from 1932, Chisso Corporation knowingly discharged wastewater from acetaldehyde production from its Minamata factory, expanding production in 1952.

The first case of what was at the time an unidentified medical condition occurred in April 1956; by October a Kumamoto University Research Group had identified it as heavy-metal poisoning caused by consuming fish and shellfish from Minamata Bay. In 1959 the company installed a “Cyclator” purification system which was later revealed to be completely ineffective. By 1962, 121 victims had been diagnosed, of whom 46 had died, and the wastewater sludge from the factory was proven to be the cause. (“Pollution was so heavy at the mouth of the wastewater canal, a figure of 2 kg of mercury per ton of sediment was measured: a level that would be economically viable to mine… Hair samples were taken from the victims of the disease and the Minamata population in general. In patients, the maximum mercury level recorded was 705 parts per million… compared to an average level of 4 ppm for people living outside the Minamata area.”*)In 1968 the Japanese government finally announced officially that Chiso had caused the pollution.

In 1969 nineteen families filed a lawsuit against the company. In 1971, a “direct negotiations” group of survivors and supporters began sit-ins in Minamata and in Tokyo in front of Chisso’s headquarters; union members physically attacked group members (and Gene and Aileen, who were photographing the protest) at Chisso’s Goi plant in January 1972. The families won their court case in 1973 and Chisso immediately paid out 937 million yen (the equivalent of US$3.4 million at the then exchange rate) in compensation. Eventually, from 1970 though 1991, 784,000 cubic meters of sludge was dredged from Minamata Bay before the area could be declared safe again. By 2007, a total of 2,668 people were certified as patients suffering from Minamata poisoning.

As Gene and Aileen conclude in their book, Minamata, “The morality that pollution is criminal only after legal conviction is the morality that causes pollution.”

* www.bu.edu/sustainability/minamata-disease/

KJ: When you first met Gene in New York, what was your impression of him?

AMS: My first impression, well, first of all, I didn’t know anything about photographers. I mean, if somebody asked me, well, somebody must be taking these photographs, I might have gone, “Oh, yeah, I guess so.” That was about my level of consciousness about photographers. I was handed Gene’s book the night before; I was tired, and I kind of flipped a few pages and went to sleep. I think it was a very good thing that because I was never interested in photography. I didn’t have any of this sort of, “oh, he’s this great photographer and I’m getting to spend time with him.” I never had that, right from the beginning.

How did you both get involved in supporting the victims of industrial methyl mercury pollution in Minamata?

I helped Gene do his quote unquote, final exhibition and retrospective in New York, called “Let Truth Be the Prejudice,” a very complicated title. His idea was, we all have our own prejudices we grew up with, we have different backgrounds. So “let truth be the prejudice” is his way of saying “may our prejudices and prejudgments be as close to the truth as possible.” And journalism is one way of introducing people to situations and things that they may have had previous prejudgments about. They learn more about whatever it is and change their prejudgments. Even if they don’t have direct experience, they are closer to it in its reality. That was at the end of August 1970. That October, Motomura Kazuhiko visited and he wanted to bring Gene’s exhibition to Japan. He had retired from civil service to start his own publishing company. He knew about Gene’s photography of WWII, Maude Callen, a black nurse midwife in South Carolina, Hitachi—he went to photograph all the Hitachi factories in Japan, ended up staying a year, and it got into Life magazine as “Colossus of the Orient”—also Schweitzer, Gene had been in Africa and photographed Schweitzer. That essay is what made Gene quit Life, because of editorial differences. He did not want to make Schweitzer a saint, just show the real person. That was back in ‘54.

Mr. Motomura was a supporter of a kōhatsusurukai group that was helping Minamata victims to rise up again and fight the company. He said, “There’s a place called Minamata, would you want to go and photograph there?” And the moment we heard that, the first time we heard that people could actually be killed by industrial pollution, we just immediately, without hesitation, knew we wanted to do it. So we said yes.

The reasons we wanted to go were all sorts of things. One was Gene felt that his former life had been somewhere in Asia, in what he calls Japan, but not politically Japan, it’s this region of the Pacific. And for me, it was like Urashima Taro—Rip Van Winkle—going back to post-war pre-Olympic, before an overhead highway was built going across Roppongi very close to where I had lived. I had never been to Kyushu or a village or small town and lived there, yet it felt kind of like homecoming to the Japan I remembered when I was little. So it all tied in. I think Gene felt that he would lose me without this, too. Nothing hung us together, then as soon as we heard about Minamata it really solidified us.

He said, “There’s a place called Minamata, would you want to go and photograph there?” And the moment we heard that, the first time we heard that people could actually be killed by industrial pollution, we just immediately, without hesitation, said yes.

You didn’t have previous experience with photography, but you were a working partner in the work that you did in Minamata.

Almost to the year from the day I met him we had already traveled to Japan and had opened the show in a Shinjuku department store, and got married on August 28th. During that year in New York, we didn’t go on any photography assignments. But because it was a retrospective, I was totally immersed in the whole span of his work and why and how he did each one. It was almost like I lived through his career, in the sense of not like going through it directly, no direct experience of being in thirteen invasions or in Wyoming photographing a country doctor or in South Carolina or Africa, etc. but because he was trying to compile all of it as his final statement, he talked it out and relived it all with me, explaining it all. So I had all of that already as part of me.

Gene gave me the Fujica that was given to him as a gift from Fuji Film. After several weeks, the camera was almost part of my body. In the loft, everybody just always had their camera with them. The darkroom work was mainly Gene and I—I had already been in the darkroom tons and tons of hours over that year, but I never even one split second thought Gene was my teacher. It’s a very interesting way of teaching where it just doesn’t feel like teaching at all, it is just living it. Usually with teaching you start with easy things and you work on this level or that level. But one print that got used as one of the prints in the museum was the very first one I ever made in my life. We didn’t even develop a batch of negatives until several weeks after I was there. Then proof printing was much later, so the order was completely topsy-turvy. I think it’s a hint for a lot of learning. It’s much more holistic. You keep doing different things and then you pretty much have learned from the beginning. So I had experienced all of that already, before arriving in Minamata. Actually going to different places photographing was a first. But I already had shot many, many, rolls of film, and photographing was already kind of part of me.

When you went to Minamata, was that just an initial visit or did you actually move there?

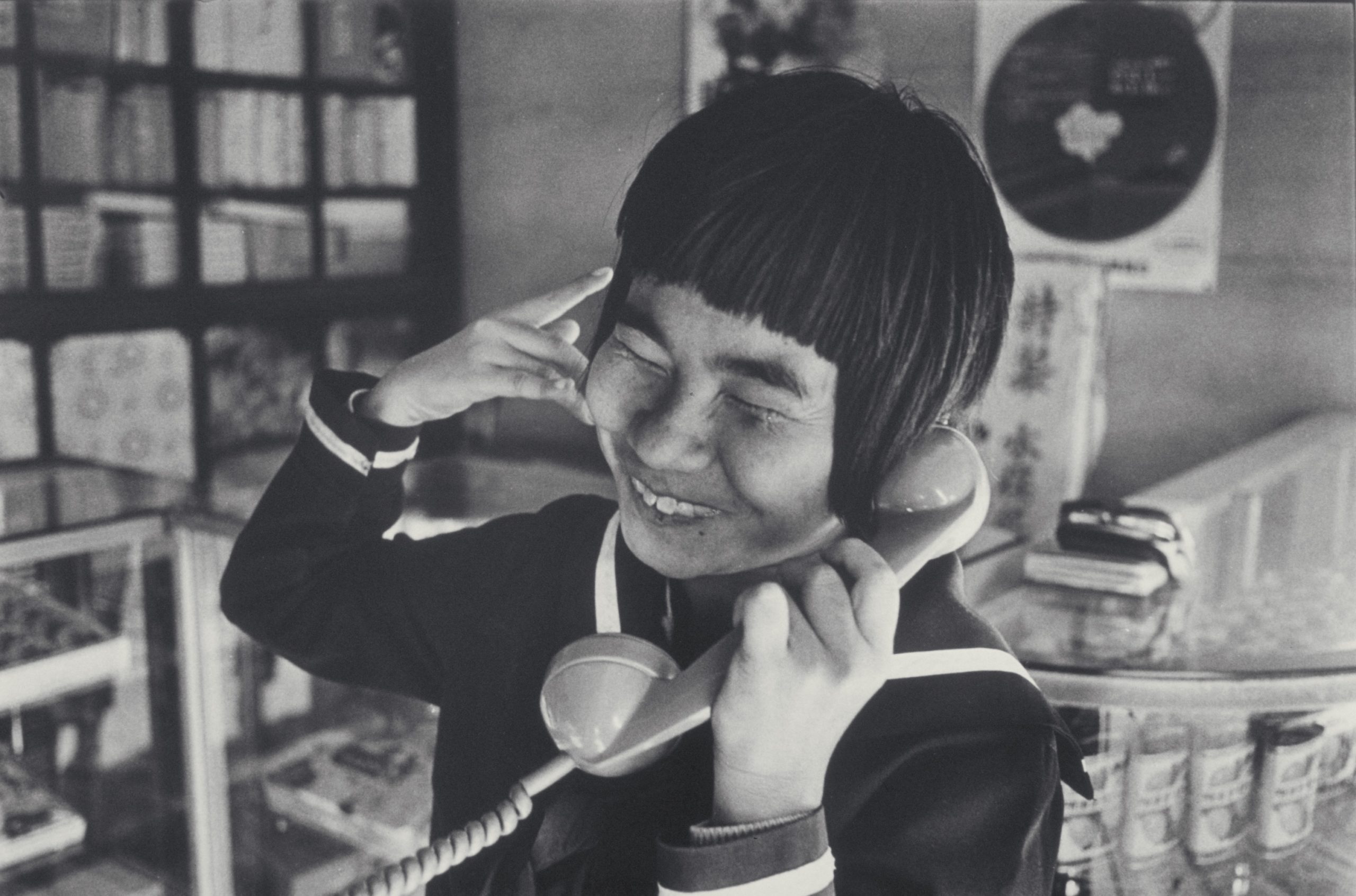

The first time we went, the first day we got there we found a house to live in. We were very lucky. Many photographers had photographed in Minamata and it wasn’t easy for them at first, for example Kuwabara Shisei in 1960, 61. We went there at a very different time when already lots of media had been there, and if anything, patients were burned by people coming in, intruding and shooting for 30 minutes and then leaving, just using them as an assignment. But a photographer named Shiota Takeshi was living there and photographing, in his late 20s. Mr. Motomura arranged for him to show us around and gave him an assignment for Asahi Graph on ‘Eugene Smith, Minamata wo toru,’ something like that, so he got to do this job and get published. And through that we got shown around the whole place—Minamata Bay, the waste place up at Hachiman, the whole orientation of where the villages were badly hit—and very importantly, the key people to meet. He introduced us to them, so it wasn’t like going there cold.

It would have been especially hard as a foreigner.

Well, I think in a way it’s harder for a Japanese person. With a foreigner, it’s harder to refuse—it’s like you’ve come from all the way across the world. It made a difference that we were going to live here, not like, oh, we’re here for the day.

At that point, did you imagine you would stay so long?

No. The idea was to stay three months, the whole fall. We arrived in the first few days of September ‘71. There are four main villages or hamlets within Minamata city to the south, right by the bay, and three of them are just walking distance, within 20 minutes. In the middle of that is where we got our house. Our main house rent was three thousand yen a month, the darkroom was two thousand yen a month. Even that five thousand was a hefty fee for us to gather. We didn’t have any kind of stipend or anything, we just went there.

How soon were you showing images of Minamata?

The first real putting it together was Life magazine, June 2nd, nine months after we arrived.

Was that when the company realized that Gene was working on this?

Oh, they knew from the day we arrived. There were no foreigners around. They knew. We even actually went inside the factory and interviewed Chisso. And their point was, “It’s just 10 to 15 parts per million, and it’s just so minute and you put it in the vast expanse of the ocean, and how could we ever know?”—that was the kind of talk they gave us. Of course, they knew their secret cat experiments had produced Minamata disease, and then they hid that fact and diverted the effluent water to the Minamata river, which then polluted vast expanses of the Shiranui Sea. We knew that they were giving us a completely false picture. We already knew what had really happened.

We went there at a time when already lots of media had been there, and if anything, patients were burned by people coming in, intruding and shooting for 30 minutes and then leaving, just using them as an assignment.

The photograph of Tomoko in the bath was taken three months after we arrived, in December of 1971. Right before that, there was a sit-in of newly-certified victims (who Chisso considered were “new patients” and therefore in a completely different category, so they didn’t have to pay them) in front of the factory in Minamata, from November and then there was a sit-in in front of Chisso headquarters in Tokyo. We wanted to go but we didn’t have the money. Finally, we scraped together the money and we went, and the first action was January 7th, 1972, right after New Year. The action was to go to Chisso’s Goi factory, in Chiba, because pro-company union workers were helping the company guard the fourth floor of the headquarters in Tokyo— the building was right in front of Tokyo Station.

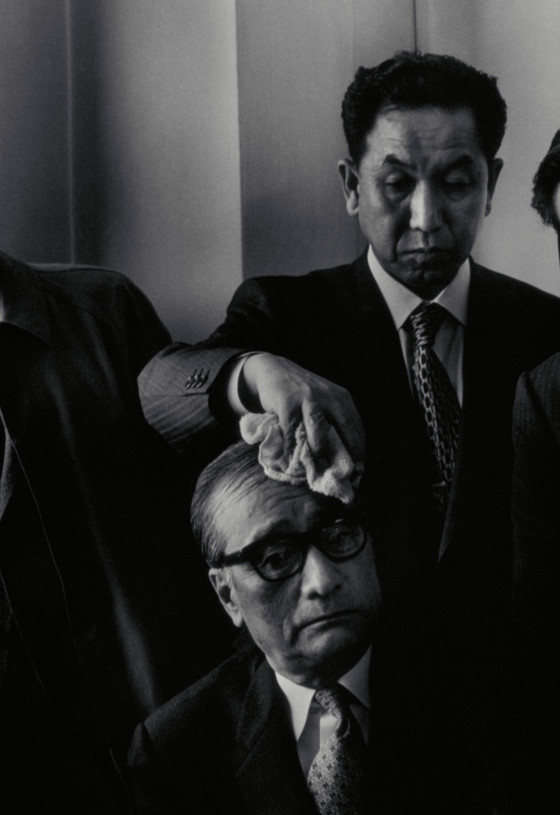

The idea was for a victim, Kawamoto Teruo, and a group of supporters to go and talk to the head of the union saying, “Don’t do that. You work for the company, okay, but don’t be goons for them. Don’t be security guards for the company.” So we went and photographed. There was also media. We waited and waited for the head of the union, but he escaped by a different exit. And as we waited, the goon squad came and beat us all up. Gene was beaten up more severely. That was exactly four months after we arrived.

Were you attacked as well?

Yeah, we were all attacked. I got my hair pulled and I was mauled and pushed around and thrown out of this little security building where you wait to go into the factory. They didn’t give us any time to escape and they blocked the entrance so it’s not like you could just leave—they just said leave now or else, and then bang, all of them flooded in and beat us around and pushed us out. So Gene got beaten up—they threw him to the ground inside the security office and then they dragged him outside and on the cement, they pushed the back of his neck into the ground, that’s where he got the pinched nerves. It wasn’t that he couldn’t see anymore, but after the nerves got pinched, he had lots of trouble seeing, and a lot of pain. So we lived with that, from that day onward. Before that he’d had a couple of plane crashes, he’d had lots of accidents and of course the main war injury of Okinawa—a hole on the top of his mouth, his dentures would just not work. And a lot of pain in his legs and other stuff from the war. So it was already pretty heavy duty, and then we just got this bigger load on top.

The photo of Tomoko in the bath was very influential. How did it become known? How was it interpreted?

Well, it got known all over the world as a result of publication in Life. After that there were requests to republish all the time, which we answered. I think people were just incredibly moved by the photograph. Millions of people have seen it. It’s an iconic image that people can identify and also, it’s powerful that you can see through the handicap. I think that people just see the connection of the mother and the child, the two of them, and the love that they feel.

It’s very universal, not simply as a post-industrial accident.

Right. And you don’t see it just a pollution issue. I think you see it as life, but each person sees it differently or it resounds in them differently. I feel that the photograph is completed when the viewer sees it. And whatever happens inside that person is the final product. So I want to give an opportunity to have people experience that.

But, I’m still honoring the the agreement that we reached with the parents, of not releasing it further. The parents don’t want it out anymore. For the last 20 years, I have used my copyright to say no to further release. But I’m going to release it through discussion with the parents if the book gets republished, and for a few moments in the movie, because they simulated the scene. Without the real photograph, the simulation would be the image that exists, rather than the real thing, so although my agreement with the movie people was not to show the image, I said yes. I actually got a ticket to London, went and talked to the director for two hours, said yes, and came back. On my own money.

For many people their whole life changed from seeing this photograph. When it hits somebody in junior high or high school is where it’s the strongest. A person that was 17, who felt a chip on his shoulder, who had never been loved, saw this photograph and it just completely dissolved something inside and changed him. And Fukushima Atsuko, one of the leaders now of the Fukushima evacuees fighting in the lawsuit, says in junior high school, every single day, she went to the library and looked at this book, and she decided to go into environmental monitoring work because of it. That’s her whole career. She said, “You just changed my life.” That’s why I want to republish the book.

But it’s not going to be that easy, because that was 1975, and it’s much harder to publish books now. Right now I’m showing it to one publisher in the US, and a Japanese publisher wants to publish. If it gets republished, maybe it might invent something new again.

We all have our own prejudices we grew up with, we have different backgrounds. So “let truth be the prejudice” is Gene’s way of saying “may our prejudices and prejudgments be as close to the truth as possible.”

Somehow, that book became a screenplay. How does it feel, to have parts of your own real life depicted in a Hollywood movie?

It feels like your life is kind of ripped off of you. Gene and I were partners in this work. It was a unique partnership—he as a veteran photojournalist doing his final work, me doing my first—the two of us were one. We took a similar number of rolls of film. Both our photographs are in the book. It’s seamless. I cherish that reality. The movie doesn’t show any of my photographs. The reality that a lot of people who see the movie are going to think [happened] is not necessarily the reality that happened to me or us. In a way that hurts, and it bothers me, but I’ve had a sort of epiphany. It’s about letting go. A child is born but you don’t own it. The child creates its own life. By letting go in this way, the message Gene and I wanted to convey, and the message about who Gene is and what he believes in reaches not just a far wider audience but many more kinds of people. It’s a kind of different message, but the more I see this with a wider vision, the more I feel the essence is portrayed. The more people taking part in this creation the better. The impact the movie had at the premiere at Berlinale (Berlin International Film Festival) made me feel very strongly that it was worth it all. At the same time, I’ll continue myself to tell our story and— importantly—the story of Minamata.

Does it show Eugene as you would like him to be remembered?

I told Johnny that there was one moment, it was up high on a building, and they were outside filming, it was almost like, oh, Gene’s out there, and I haven’t seen him a long time, I’m going to go out and see him, kind of… really. The resemblance is uncanny at times. I don’t know how they did it. Looking at Johnny up close, I really didn’t see any make up. Except his voice is of course very different. I said to Johnny you look so much like Gene and he said, that’s the nicest thing someone could ever hear from somebody that was directly involved. Of course, the character in the movie is different from the real Gene. Gene never, ever would give up in front of an editor. But finally I think that it portrays him as more like him than I realized, maybe. I’m not that bothered by the way Gene is portrayed, because I think the real him is still there and so strong. There’s a biography of him that was done by a friend, Jim Hughes, who interviewed everybody in his life and has really good direct quotes of Gene’s own words, and also other people who really knew him, so I feel like it’s on record.

But I think the most exciting thing I heard was after people came out of the Berlinialle premiere. We had a flyer about what’s happening with mercury now— the levels are going up and up and up worldwide and we’re trying to get it down. There is a convention, but we want everybody to ratify it and really commit to reducing the pollution all over the world, including from coal—coal-fired plants emit mercury. When the audience came out, I had to go to the after-party with Johnny Depp and everybody, but [friends] were there handing out the leaflet that we had made. And the reaction was really exciting. They described three types of reactions. One is “I’m just absolutely flabbergasted this kind of thing could have happened in an advanced country like Japan, so completely floored that this was going on, in Japan.” Or “Yeah, sure, I’ll take a flyer.” Then for another group of people like, “It was just too much for me, I can’t even take a flyer,” that kind of feeling. And then other people said, “Yeah, I’ll grab a flyer, how many can I have?—I want to show it to my friends.”

When does the movie actually come out?

It will come out in the US next spring. But not in Japan until around September.

Do you anticipate a backlash against the film?

I think not nationally, but in Minamata, it’s going to be really hard. My main concern is Minamata and the victims, what would happen there. The city powers-that-be want the problem to go away, don’t want the Japanese public to be reminded of what happened and even more that the problem is ongoing.

The current mayor got elected with Chisso’s backing. In Minamata there will be turmoil. I even hear that conservative city legislators are asking, “Is Chisso going to be portrayed badly?” This is the corporation that killed all these people—it’s like …hello? If they complain, let’s just spell out all the things Chisso not only did do but continues to do. They appeal court cases even if victims win. So if we’re going to have a debate about Chisso being portrayed badly I’m ready for that debate. If the movie is eased into Minamata, the victims won’t get the brunt of the backlash.

What’s happening still with the court cases? What are the key points now in what’s happening in Minamata for the survivors?

The official take on the situation domestically was that the poisoning was caused by some kind of poison in fish in Minamata Bay. That official declaration was 1956, May 1st. So now how many years has that been, 64 years, right? But during the worst part of the pollution, fishing was never banned in Minamata Bay. The food sanitation law could have banned it,—if a restaurant is emitting poison, you shut it down. But MITI said that there’s no proof that every single fish in Minamata Bay is poisonous and therefore we will not ban. There have been lawsuits by a doctor and also a victim about this issue. This was somebody whose father and mother got Minamata disease and he has Minamata disease but he lost the suit because this law is to protect public health and not individuals. So you do not have the right to sue.

There has never been an official epidemiological study of this situation. No careful study of the pattern of disease, meaning “What is it? What kind of symptoms occur? And what groups of people got it?” You do a case control study in a similar area, everything is the same except that the fish isn’t polluted, versus what’s here. Not once has that been done. Most recently, a group of patients went to Koizumi, the Environment Minister, and asked, please hurry up and do the survey, hurry up! It’s 64 years since the discovery of Minamata, and it hasn’t been done. And yet, there’s a certification system that says, unless you have these kind of symptoms, you don’t have Minamata disease, so you’re shut out.

Right now, one key lawsuit is the one by a man who actually had sued under the food sanitation law, whose parents had gotten sick and he also has Minamata disease. His name is Hideki Sato, and his parents are in the book here [Minamata]. The toddlers who were living there in the peak of the pollution grew up being told Minamata disease is only that acute stuff that your parents have, or the bedridden congenital victims or the people who died, that’s Minamata disease. And now, no problem exists, and etc. So they grew up their whole life, thinking, this is just my body, I get convulsions sometimes or I’m numb here, but gradually realizing, hey, everybody doesn’t have this, you know, there’s a cause to this. An outside industrial cause. Realizing it took time too, and then they sued. So these toddlers, they’re now in their mid-60s. And they won a case and still Chisso and the government appeals the case. So now they’re in appellate court. That’s the current status today, in appellate court, toddlers of 50 years ago, or 55 years ago, still suing. Now they just look like ojisan or obasan [grandparents]. But I always say you should find the photographs of them when they were little.

It’s not like something you have that you stopped having years ago, you’re still having it. There’s pain and there’s numbness and there’s things you can’t do because of it. And you’re just living with it all the time. For example, Hideki’s wife, she’s saying, I’m driving with the kids in the back, going 40 or 50 kilometers an hour, and suddenly I can’t feel my hands. I can’t feel my feet. And she says it’s terrifying.

[See Part 2, here]

All photos courtesy of and subject to copyright by Aileen Mioko Smith.