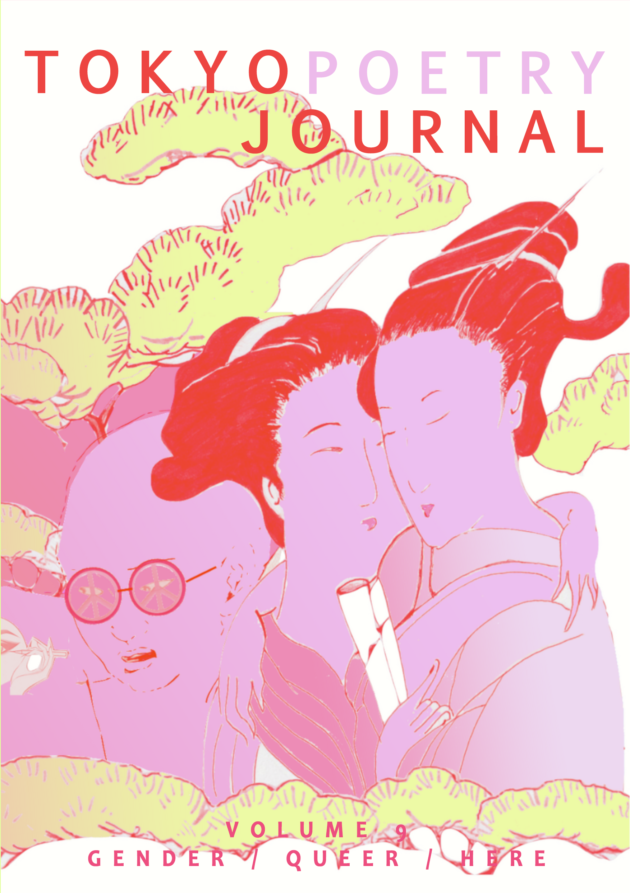

Tokyo Poetry Journal, volume 9: Gender / Queer / Here, edited by Barbara Summerhawk – reviewed by David Cozy

Tokyo Poetry Journal, volume 9: Gender / Queer / Here, edited by Barbara Summerhawk. 214 pp., ¥1500.

Editor Barbara Summerhawk explains in her useful introduction to the “Gender / Queer / Here” issue of the Tokyo Poetry Journal that in selecting the poets whose work appears in this volume she was taking a big tent approach: “ . . . there are no divisions in this book between lesbian/gay/bi/trans/intersex/asexual/ally; some poets have chosen to identify themselves a certain way in their bios, others have not.” Likewise, some of the poets included choose to write explicitly about their sexuality while others write poems that seem untethered to a particular sexuality, or even unconcerned with sexuality. And this is as it should be: one would not expect an anthology of heterosexual poets to feature only poems concerned with the poets’ sexuality, nor should one expect gender non-conforming poets—Auden, say, or Marylin Hacker, or Ginsberg—to write exclusively about their homosexuality. It’s a wonderful thing that this journal does not limit itself in those ways because this allows both poets writing explicitly about their sexuality, and those who write out of that experience, but not explicitly of it, to shine.

Just as it is unnecessary, though perhaps delightful, for a poet to place their sexuality at the center of their work, it is unnecessary for readers to let authors’ sexuality, whether explicit or implicit in the work, determine their reaction to those authors’ poems. The question is not who does the writer sleep with, but are the writer’s poems any good.

Most of the poems Summerhawk has chosen are good, though as is always the case with a collection as wide-ranging as this one, it’s hard to imagine a reader who would enjoy each of the collected poems. The occasional poem that doesn’t work, though, is more than made up for by the pleasure of discovering poets whose work one is unlikely to have encountered elsewhere.

We are immediately arrested, for example, by the first stanza of Cheiron McMahill’s “AFTER FOUR YEARS”:

Morning in the mountains is

wind of smoke that hurts

pine-needled air,

wet earth.

The poem concludes with lovers inside:

we embrace

the warm silence hovering

between us.

Hour after hour by the fire

one cannot be separated from the other;

the fire and the sparks.

The mountains outside, the warmth inside, recall Gary Snyder’s “After Work.” In that his poem, also about lovers getting warm inside a cabin, is explicitly heterosexual (and depicts gender roles at their most traditional), it seems, however, more limited than McMahill’s. She leaves the gender of her couple undefined, and thus is perhaps more welcoming.

Translator Jeffrey Angles, we learn from his bio, “believes strongly in the role of translators as social activists,” and one way this has manifested itself is in his translations of queer writers, foremost among them, perhaps, Takahashi Mutsuo. Takahashi, like many gay authors before him, has drawn inspiration from “Greek love,” the notion that love between males was accepted and encouraged in ancient Greece, and has used it to critique contemporary common sense. He looks, for example at two urn paintings:

The bearded man on this painted urn stretches his finger

To caress the foreskin of the boy before him

On another vase, a man reaches to hold in his palm

The pulled-back testes of the adolescent facing the other way

One could easily call these obscene, but why not think in metaphors?

Could he be giving stimulus to the tip of youthful sensibility

Or warmly renewing the crux of the fresh being of youth?

Is it wrong to sing songs of praise to Greece

Which discovered eros at the heart of education?

Takahashi’s quiet erudition and wit will open the minds of even those inclined to disagree.

The poems discussed above will, in their elegant simplicity, be easy enough to read. Others, such as Ryoko Sekiguchi’s poems from her Luminescent Diapositive, also translated by Angles, will be more challenging, and are essentially impossible to excerpt from in that part of the pleasure they offer has to do with how readers move, guided by arrows, among the fragments Sekiguchi gives us. In what appear to be instructions that precede the poems (but might actually be one of the poems), Sekiguchi writes: “What should have been a single line suddenly becomes an encounter in a crowd,” and we’re glad her poems weren’t reduced to a single line. Where’s the fun in that?

Even just the three poets considered in this review—Japanese, not Japanese, female, not female, avant-garde and otherwise—give a hint of the breadth of this anthology. The three, however, are just a taste of the twenty-three poets included in “Gender / Queer / Here.” It should be required reading—university professors, are you listening?—for anyone who hopes to move themselves or their students beyond the heterosexual pale of poetry from Japan.

David Cozy is KJ’s Reviews Editor.