[O]ne might say that the role of the artist is to manifest divinity. More than simply providing a “view” of life, the artist documents her continual search for divine realization. Moreover, artists, by sharing their work, involve everyone in that search.

Graphic artist Mayumi Oda’s cultural, spiritual, and artistic odyssey has taken her through many lives, eras, countries, and incarnations. Born in Tokyo, 1941, to a Buddhist family, Oda writes that from an early age she felt attuned to the changing seasons and their rituals—the Tanabata Star Festival, the Obon Festival of the Dead, and New Years. Monthly memorial services for her grandmother, wherein the Lotus Sutra was chanted, gave Oda a religious orientation which she has never forgotten. She also became acutely aware from an early age of the inferior status of women in Japan—a condition unchanged by the otherwise ambitious “new democracy” of the post-war years, a condition which remains stubbornly intact today. Later, as a student at the National Academy of Art in the early 60s, Oda was to feel stifled by the traditional approach to art instruction, and sought to develop her own individual style. Her marriage to American scholar, translator, biographer John Nathan seems to have offered temporary relief from her feelings of social and artistic frustration. Marriage took her away from Japan. Life in America during the tumultuous 60s exposed Oda to the likes of modern writers, musicians, activists, and artists, as well as the various social movements which characterize that unique decade including the full force of women’s liberation. Separated from Nathan in the next decade after several years of marriage and two sons, Oda decided to direct her attentions more assertively to the spiritual life—a life which has embraced social activism. Oda’s sense of spirituality combines elements of Zen Buddhist practice, a universal reverence for life, and respect for the individual—all of which are visible in her artwork. She eventually settled in Northern California where she lives to this day.

A collection of her artwork has been collected in the book, Goddesses, recently made available in Japan from Gendaishuchosha Publishers in a bilingual edition. For this third printing, Goddesses appears on a special rice paper called takebaraki—the first such book to be so published. Virtually indistinguishable from wood pulp paper, bamboo paper nevertheless creates an added dimension to the printed experience, and compliments the simple voluptuousness of her subject matter. In addition to a lengthy introduction to her work, Oda has provided a commentary on each of the book’s 31 prints. Oda’s colorful silk-screens, instantly recognizable for their sense of primitive majesty, have graced the covers of several books, including Gary Snyder’s Axe Handles and the late Rick Fields’ How the Swan’s Came to the Lake. (Incidentally, on July 7, 2000, tanabata, a special exhibition of Ms. Oda’s work opened at the Daimaru department store in Kyoto.)

In Mayumi Oda’s life and work, several elements converge—Buddhism, feminism, art, ritual, social activism, mythology, motherhood—filtered through her bi-cultural life experience. Ironically, after initial disappointment and frustration in many of these fields, Ms. Oda has succeeded in transcending the secular corruptions these institutions. In the process she has emerged as a renaissance woman. It is only as liberated individuals, Oda’s life and work seem to suggest, that we can bring our love for live, art, and beauty to fruition, and only then can we become acquainted with the gods and goddesses within us.

If you remained only in Japan, without having gone to America, do you think you would have become who you are today?

Mayumi Oda: Of course not. I think I had a dream a long time ago. I became an “over-sized tatami” and my mother was trying to fit me into a four-and-a-half mat [yo-jo-han] tea room, chashitsu, sitting on me trying to fit me into the room. That’s what I became, an over-sized tatami. I don’t fit in here, in Japan.

When did you first go to America?

In 1966.

Anything special take you there?

I was married to John Nathan, a translator and Yukio Mishima’s biographer. I was married to him for seventeen years. It was a very interesting marriage. I learned a lot from him. You know, I think about karma, what kind of karma that I have. I met a lot of people from Mishima Yukio to Oe Kenzaburo to Kawabata Yasunori—incredible writers in the 60s. I was still a student at geidai (the Tokyo University of Fine Art). I was a freshman and married to John Nathan. We went to New York in 1966. It was an amazing time. Then, I was introduced to Barney Rosset, who owned Grove Press. Remember the Evergreen Review? Barney published Oe Kenzaburo so I learned an immense amount of culture from this man. Beckett, Pinter, Burroughs, Ginsberg—from Japanese literature to Western literature. John was a columnist for the Evergreen Review so we got involved with the psychedelic experience. Then he became a junior fellow at Harvard University, and that’s where I was “baptized” by women’s liberation. It was incredible.

Those were the years …

After that, my marriage began to fall apart. John became a film-maker, and about that time I decided to develop a spiritual practice and chose to live in California.

How to become who you really are often takes you away from your own culture.

Yes, definitely. I think a bi-cultural person can really offer an incredible perspective, and be a bridge between two cultures. Bi-cultural people have a completely different view of the world and have so much to offer the world.

Well, I see a multiple persona in you as an artist, as a woman, as a Buddhist, as an activist, ….

Being bi-cultural.

Yes. Do you see these elements of your personality as hierarchical, is one aspect more important than another?

It’s all the same. I didn’t do any art work for six years, from 1992 to ‘96, since I took up my work against plutonium. I did not miss painting much. I was so absorbed in doing political work.

So that was taking your art energy.

I was using my same artistic energy and applying it to another field. I didn’t even think about it. I worked with Tanahashi Kazu [translator of Dogen and editor of Moon in a Dewdrop, an anthology of Dogen writings], a very wonderful man. He feels the same way I do, although we are working in a different genres.

What was your purpose in coming to Japan this time  [summer 1999]?

[summer 1999]?

Mostly to use this opportunity, or rather, this occasion of the Tokaimura accident was very critical in terms of the anti-nuclear work that I’ve been doing. So, I want to use this critical moment to turn people and their helpless feeling around into something more positive. People really feel frightened about the accident. They are also frightened about the Japanese government’s irresponsibility in handling the accident, realizing that there is no leader. There’s no political people taking care.

This seems to be typical or symptomatic. During the Kobe earthquake, for example, or previous nuclear accidents like the one in Mihama , there is the government voice which explains and yet there seems to be another community voice underneath that which is not heard. I would presume that one would want to give voice to people who are victims or those who suffer from such a devastating event.

These survivors have been completely neglected and not taken care of. It’s really terrible.

Does this lack of responsibility strike you as “business as usual”?

I think so. I think this kind of attitude led Japan into the second World War. Not really paying attention, being very obedient, or thinking that the government, our government is a good government and therefore will take care us. We do not understand that we, the people, are the government. I think that Japan is not democratic in that sense.

I think all governments manufacture a mythology that it’s safe “here” and dangerous “over there” or outside the country, and many people profit from this mythology whether its the Japan Travel Bureau or …

Absolutely. The weapons makers or the nuclear power brokers also tend to be the same, the same people making a profit.

I don’t think communities buy into that thinking as easily as say urban residents who live in these huge apartments and have little community feeling.

So that’s one of the reasons I came here, to use that opportunity to talk to women. I have a mission to arouse Japanese women consciousness about the Toukaimura accident. There are women who I’ve worked with in the past. They used to be called Rainbow Serpent. We had a group called Rainbow Serpent who worked against plutonium shipments in 1992 in Japan. We had to cease being a network because we were severely harassed.

Harassed? By … ?

By…we don’t know. Possibly thugs hired by the utility companies. We were a very good women’s network called Plutonium Free Futures. In 1992, we formed another group called Inochi [life] in Berkeley, California. We are committed to do anything which will help sustain life. Our main focus is to bring an end to nuclear industry and offer alternative energy future.

What shape did the network take?

Very small. We worked as a bridge or liaison between Japan, America, and a larger international community. We tried to be a liaison.

You say this was a very small network and yet you were being harassed? Small and yet still threatening enough to warrant harassment?

Yes, these are very powerful women and they lobbied very hard against the government’s Science and Technology Agency, and MITI [Ministry of International Trade and Industry], and so forth. We also tried to bring an international lawsuit against the Science and Technology Agency for their transport of plutonium. I think it was threatening enough because we used very powerful lawyers. All this work was very new for me so I was learning and using my creativity. It was tremendously fun.

Fun?

Oh yes! It was very difficult but also very challenging and rewarding. Very interesting. We went to many international conferences, both big and small. I even went to international conferences registered as a Non-Government Organization [NGO] group and started a lobby. I went to the World Court in Den Hague to make nuclear weapons illegal. The World Court has two basic functions: to settle international disputes and to offer opinions on international matters, for example should nuclear weapons be illegal. This was that case and it was called the World Court Project. Although it was an NGO project, many countries were involved. We worked with various countries opposed to nuclear weapons. I got involved as an international coordinator and it was very fascinating to learn. The World Court is a little more cordial that the kuyakusho [the local ward office].

Can you comment on, or give an example of, the political aspect of your art work.

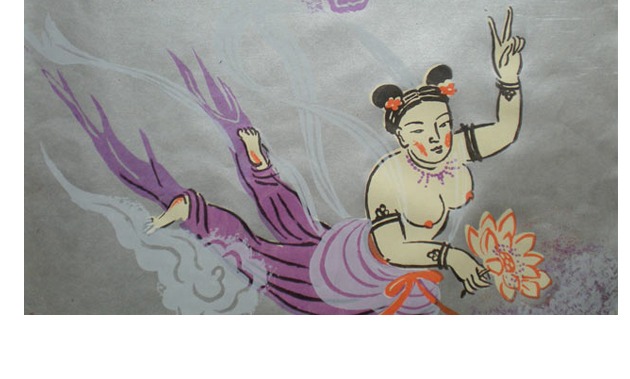

To me, for example, this cover picture of Goddesses. It’s Kaba a very famous wind god, a thunder god and it’s a male god and it’s angry. Now he’s stripped naked and made into a female. I could only do that after I had gone through women’s liberation. I found that women’s liberation not to represent my whole liberation because they are still blaming outside, patriarchal forces. Somehow I felt like taking all their clothes off. This, to me, is my statement. I don’t say this as an abrupt, political statement because there are always other forces at work. I think the great thing about art is its totality. It’s not just a single, exclusive gesture.

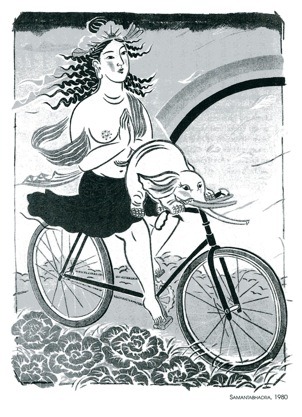

I would agree that art is a wide road and there’s room for everybody and all things. Speaking of “on the road”… I’m thinking of an image of yours where you placed a couple bodhisattvas on bicycles.

Manjursi and Samanthabadra—I made them riding bicycles.

Now those images strike me as very political statements because Manjusri is of course an image of power, and yet the goddess is not on a motorcycle or an airplane or a jet but she is not just sitting still in isolation either. The image is in motion, or rather a suggestion of motion on a bicycle.

Well, I used the image of bicycle posters at the turn of the century. They really thought of the bicycle as means of liberation.

… into the future.

Especially for the women. With pantaloons, they would ride a bicycle and felt that, you know, the bicycle was an extension of their power.

A main question in Buddhism, I think, is how do we get to the future, and Bodhisattvas show us how to get to the future. Yet Bodhisattvas can be male or female. How have men responded to Goddesses?

Interestingly, I had a book signing in Ikebukuro, Tokyo recently [summer 1999]. 150 people lined up and there were a lot of men in their 30s and 40s. I had no expectation that men would be interested. It took so long to sign these books because each man wanted me to write something, not just my name. So I mostly wrote “megami no chikara to yasuragi o” (“… the power of the goddess is healing and comfort”).

My experience as a man is that this social/sexual identity overhaul is a kind of cleansing. It’s a little rough but you come out cleaner and stronger at the other end. Another feeling you get from your images is a sense of healing, another kind of healing which can be nurturing, spiritual and I think that is conveyed in your work.

I hope so.

Well, I see the motivating image, the catalyst, in your work is definitely feminine. I think that your images serve as a mirror for men to locate the feminine in them.

Definitely all of that is within us.

I think your art work also addresses psychological issues in women. I think the secrets that your images being out in men also bring out something in women which may have repressed or dormant.

For women, their femininity is challenged too. To me, especially, since I was in America, I needed a lot of strength. I had to come to grips with my strength. I had to practice to feel comfortable because you don’t want to take advantage of this nurturing mother type. One is very cautious about it. A lot of women’s movements deny that nurturing feminine side and that’s probably the part because they perceived enemy as outside them.

That matriarchal force is very scary for men because it’s life creating.

It’s where you came from.

Then there’s also that black Kali, consuming side and that is scary for men. Men forget that it’s also scary for women. I think that women have a process they go through, coming to terms with the feminine in them, as men do.

Especially in our times, which are so threatening. The women can become so strong.

I think we’ve seen that the masculine political response to the problems of modern life is not what we’ve needed. They’ve been inadequate. I think what we’ve learned from the women’s movement and women’s psychology is that we need to nurture and create . That brings us back to art. Did you have art training as a child?

Well, I’ve been painting since I was two or three, and I just never simply stopped.

Did you go to art school, art college?

Tokyo Geijitsu Daigaku, the Tokyo University of Fine Art.

The reason I ask is that the art world tends to be divided into the professionals and the primitive. The primitive tend to be those who were inspired later in life and simply expressed themselves freely without prior training. I see elements of both the professional and the primitive in your work.

Well, I had to give up what I learned academically, my school training. I tried to give up everything and go back to the roots of creation, like a child.

Is that possible? Can one’s professional training transform to another more primitive form of expression?

I don’t know if one can actually throw it all away or not. I don’t care whether I have thrown it out or not. All I care about is if I am expressing what I really want, what is most important. So, sometimes my training is very useful, it definitely comes through in the painting. It’s not so much the technique but the discipline. I think what helped me was the kind of discipline that I went through. I am willing to go the discipline if I have to, to express myself. It’s sometimes monotonous to achieve a certain effect and I have to really work on it. Though my art is not so technically based. I try not to go through that technical superiority. That may be why my art has a feeling of primitive art. I think the immediacy of the art is very important. It’s like Rumi’s poetry and how immediate his poetry is. He had to throw all his knowledge out—from academia to that very basic place. I think it’s important to be able to live in that basic place. My Zen training taught me to be in that very basic place. I don’t like the art that shows off your skill. I am very against it ….

because …

Because it’s showing your ego—how skillful you are. Of course, that skill may be appropriate to the expression. If you need a certain level of proficiency to play Mozart, that skill is fine but so much art today which simply shows off that skill.

Yes, but in Japan doesn’t one manipulate the art form to such an extensive degree just to achieve an image of naturalness?

I think people will end up talking about the technical aspect of the art and not what it means. Today, in Japan, artists talk about what they have gone through to produce an effect so that often the art is lost.

So, for many artists, the form has become more important than the content.

Yes.

Do you teach?

I’ve never taught art. I teach a very small leadership program once a year for a small institute in San Francisco, Asian-American Women’s Leadership. It’s a kind of mid-life leadership training, basically for Asian-Pacific women.

If you were going to teach art, what would your priorities be?

I would teach creativity, the release of creativity.

How does one do that?

Through meditation. How to trace one’s own creative blockage, which is their own enemy. Where is their creative limit and locate that place where your limitation comes by using a meditation technique and then an expression technique which is very non-judgmental. Basically, like Zen.

A big problem in art and politics is making that translation from something which has been meditated upon, whether it is Marxism or capitalism or art, how one translates a concept into the body or a physical manifestation. How does one make that leap?

It’s really experiential, or sensual, something that needs to be experienced with the body.

So, as an artist, deciding the media to express your meditations is a secondary consideration.

Absolutely secondary. Media is just the body. It’s really not a theory or idea. I work with a lot of emotions, finding out our fears, our judgments.

That’s politics. I mean when a judgment which is personal is projected out upon a group, it becomes political. Do you consider your art to be political? Even though the subject matter is mythical and religious, is there a political element?

I do feel that I am very political. Yes, in the sense that I believe that we do have power and we shouldn’t give our power away. My message is that we must retrieve our own power and really bring it back to ourselves. That’s where the power is, that’s where democracy is. That is freedom.