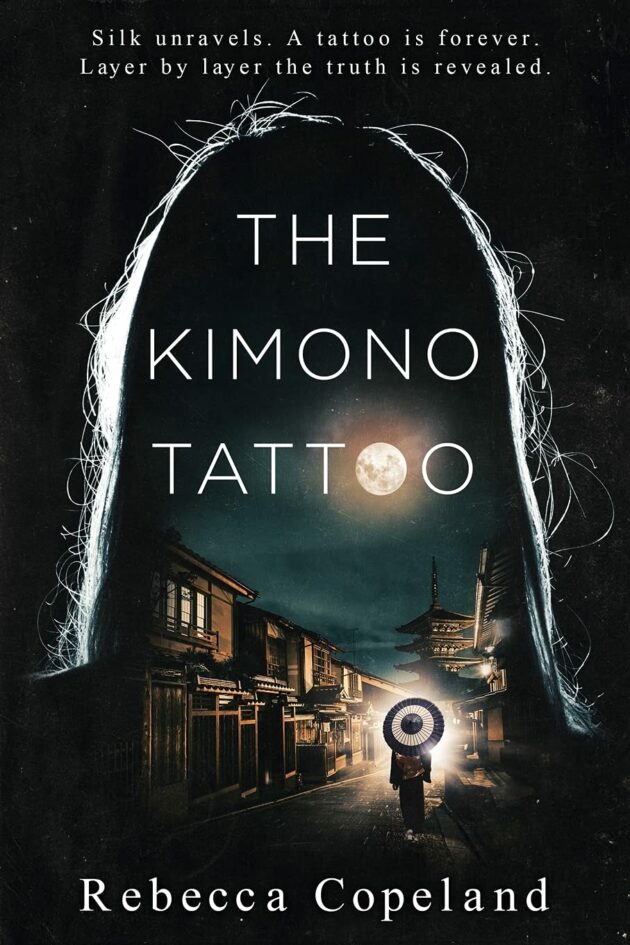

The Kimono Tattoo by Rebecca Copeland – reviewed by David Cozy

The Kimono Tattoo by Rebecca Copeland, Brother Mockingbird Publishing, 362pp

An academic out of a job getting by as a translator in Kyoto is approached by a mysterious woman in a kimono who offers her a remunerative job translating a novel, chapter by chapter, as it is written. The ostensible author of the novel, long thought to be dead, is the disowned scion of a family that has been in the kimono business for generations; the novel describes a crime: the murder of a woman with a full-body tattoo designed to look like a kimono. Add that the translator’s brother disappeared when they were both children and you have the threads—or most of them—that Copeland skillfully weaves together to give us a thriller that is thrilling indeed.

That it’s never easy to stop turning the pages of Copeland’s novel is a testament to her skill, especially when one considers the chances she has taken. In choosing, for example, to teach her readers about Japan, about Kyoto, and about kimono, she runs the risk of being pedantic in the worst as-you-know-Bob style. She manages, though, to fold what she teaches us into her narrative in such a way that, far from slowing her story to a slog, it instead makes the feverish page-turning a richer experience.

In addition, she does something that is rarely seen in fiction by non-Japanese about Japan: She gets the place right. The characters seem like people rather than exotic caricatures, and the Kyoto she creates will be recognizable to those who know it, enticing to those who don’t.

Sometimes, perhaps in an effort to paint Kyoto in its best light, she overdoes it just a bit: Surely some Kyotoites live in characterless 2DKs rather than the elegant dwellings in which most of Copeland’s characters reside? We don’t read novels like this one, though, for unmitigated reality, so even the occasional indulgence in real estate porn doesn’t go amiss. It’s more fun to read about rooms done in a “tasteful, minimalist style, a hinoki slab table in the center, and a single cushion,” than the plastic of a unit bath.

The prose in which Copeland tells her story is efficient: It moves things along, and that’s as it should be in this kind of novel. There are, however, moments when Copeland’s writing rises above the merely serviceable as when she describes the mysterious kimono-clad woman who hires our protagonist: “I caught a glimpse of her teeth. They were deeply discolored, perhaps from smoking. . . . The contrast between the decayed interior of her mouth and the genteel nature of her gesture was a bit disconcerting.”

Copeland does something that is increasingly rare in genre writers: she doesn’t seem to be setting herself up to write a series of books featuring her translator-sleuth. The loose ends are all neatly tied off at the end, perhaps because Copeland has a day job as a professor of Japanese language and literature and doesn’t need to support herself by making up stories. Still, this story is so much fun that one hopes she lead us on another Kyoto adventure.

David Cozy has been KJ’s Reviews editor for over a decade, since KJ76.