Text and photos by Marc Peter Keane

The year is 612 CE, the place, a kingdom in Korea known as Baekje. A man stands at a crossroads with a choice to make. A life-changing choice.

A serious case of ringworm has left him disfigured; his skin covered with white blotches. At a time when the causes and cures of such diseases were unknown, just the sight of him makes people nervous, aggressive even. The safe money says he should go hide hmself away, become a monk at a monastery sequestered in the depths of the mountains. But there he stands, mulling over another possibility that has come his way. A downright crazy idea. Instead of running away to the mountains, he can get on a small wooden ship and make a harrowing journey across the sea to a country he has only heard of in tales. Doing so would mean casting himself off into the world with no hope of return and trying to make his fortune among a foreign people about whom he knows basically nothing. Well, the hero of our tale must have been impossibly brave and self-confident because leaping off into the great beyond is the path he chose.

When he arrived in Japan, it was the 20th year in the reign of Toyomikekashiki hime-no-mikoto, known to us posthumously as the Empress Suiko. The realm she reigned over was in a period of rapid development as new ideas, materials, and technologies were being introduced from continental cultures. Some were imported directly from China, but many made their way through one of the three Korean kingdoms, especially Baekje. When our hero arrived to the capital of Asuka, he was in the company of many others like him who had certain skills that they hoped to parlay into a place for themselves in Asuka society. There may have been Buddhist priests, carpenters, paper-makers, scribes, weavers, and scholars of geomancy or governmental law to name but a few, but our hero was none of those. He was a gardener.

His arrival is recorded quite clearly in the Nihon Shoki, The Chronicles of Japan, one of two ancient books of classical Japanese history. Whereas earlier accounts in the Chronicles are considered to be mostly apocryphal and mythological, by the time the records reach the age of Empress Suiko, it is likely that what is written is a reasonable record of the actual events that took place. The account of our hero’s arrival goes as follows:

This year a man emigrated from Baekje whose face and body were all flecked with white, perhaps having been infected with white ringworm. Disliking his extraordinary appearance, the people wished to cast him away on an island in the sea. But this man said, “If you dislike my spotted skin, you should not breed horses or cattle in this country which are spotted with white. Moreover, I have a small talent. I can make the figures of hills and mountains. If you kept me and made use of me, it would be to the advantage of the country. Why should you waste me by casting me away on an island of the sea?” Hereupon they gave ear to his words and did not cast him away. Accordingly, he was made to create the figures of Mount Sumi and of the Bridge of Wu in the Southern Court. The people of that time called him by the name of Michiko no Takumi, Michiko the Artisan, but he was also known as Shikomaro, the Ugly Guy.

(based on the Japan Historical Text Initiative website text)

When Michiko said that he could “make the figures of hills and mountains,” what he meant was that he was skilled in the art of garden making. The note that the garden he built was in the Southern Court referred to the nantei, the open area south of a central palace hall, in this case the palace of the Empress herself. But the thing revealed in this account that has had the most long-lasting effect on the history of Japanese gardens, is that Michiko created the figure of Mount Sumi in the garden.

Mount Sumi refers to Shumisen, the Japanese pronunciation of the Sanskrit word Sumeru. Sumeru, sometimes called Mount Meru, is the sacred mountain of Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain religious cosmology. The mountain is believed to form the axis mundi or central core of the physical and spiritual universe. The mountain is described as having four sides made of precious materials facing in the cardinal directions — gold facing north, crystal to the east, lapis lazuli south, and ruby west. From those four faces issue four great rivers that flow out into the various seas and mountain ranges that surround the towering Mount Meru.

By creating an image of this sacred mountain in a garden, Michiko brought into the garden an aura of spiritual sanctity and, at the same time, created an allegorical symbol that could be used by Buddhist priests to expound on religious matters. At this time, Buddhism was in the very early stages of being introduced into Japan. The people who promoted and supported Buddhism were in direct opposition to those who promoted and supported the native religion of Japan, which we now call Shintō, The Way of the Gods. Empress Suiko was walking the middle path, trying to appease both factions. Buddhism, as an aspect of continental culture was inextricably linked to those other continental cultures that were bringing Japan into a new modern era, including agriculture, architecture, governmental systems, reading and writing, and many more. Suiko, however, as a member of the imperial household, based her entire life story and raison d’être on the ancient lineage described in Shintō mythology. Building a garden around a Buddhist image such as Shumisenwas as much a political act as an aesthetic one.

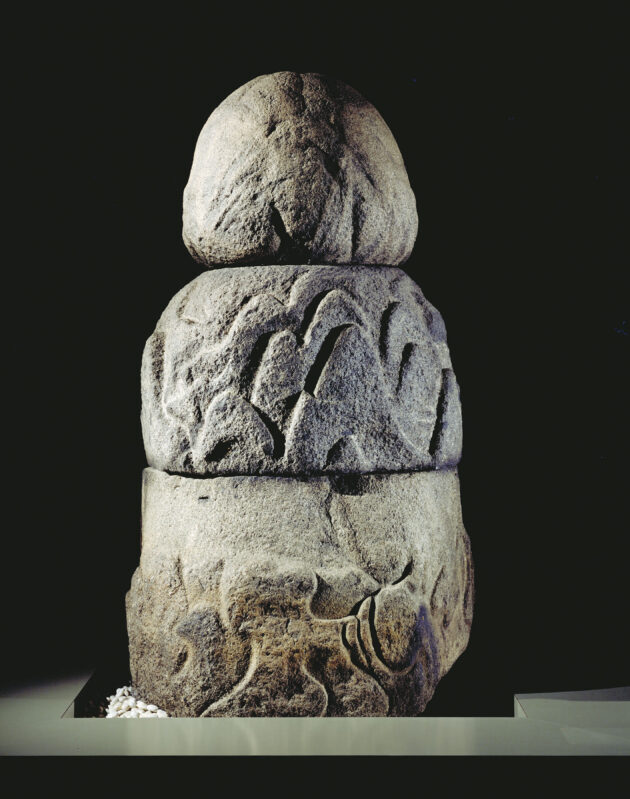

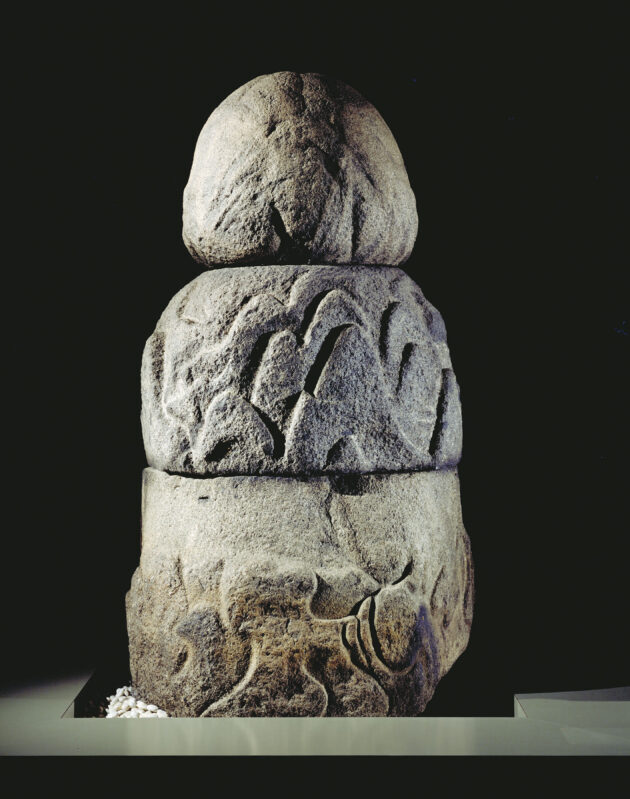

Jump forward about 1,300 years. In the year 35 of the Meiji period, or 1902 by the Western reckoning, an architectural dig about 25 kilometers south of Nara in the Asuka region found a number of interesting artifacts. Among them was a large stone carving of a Shumisen image. It was made in three sections which, when stacked one upon the other, stood about 2.3 meters high. Research has suggested that there would have been a fourth piece at the bottom so it would have been even taller originally. The sides were carved with images of mountains, and the inside was hollowed out to create a kind of reservoir. Furthermore, it was shown that if the sculpture was attached to a flowing water source, it could be turned into a fountain with spouts streaming out in four directions, just like the rivers of Mount Meru. It is believed that this garden fountain may have been the very element that Michiko installed in the Southern Court of the Empress Suiko’s palace.

Shumisen imagery continued to be placed in gardens throughout the following eras but in future years, the design changed radically. Rather than creating sculptural elements with literal carvings of mountains on the sides and actual flowing water, Shumisencame to be represented by a simple standing stone, a natural boulder taken from a forest or a river, unaltered by the human hand and set into the garden. These natural Shumisenstones hearken back to the sacred boulders of Shintō known as iwakura, and represent one way in which continental culture was modulated to better settle into Japanese society.

By the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, natural boulder Shumisen stones were used in karesansui gardens, the dry landscape gardens composed of natural boulders typically set in fields of raked sand. One such example can be found in the Muromachi-period Ryōgintei garden at Ryōgenin temple. Ryōgenin is one of the many subtemples in the large Daitokuji Zen monastery in Kyoto. The garden is on the north side of the hōjō, main hall, where the rooms facing the garden were used as the head priest’s residence and studies. In Ryōgintei the stones are placed in a field of carefully tended moss, although the original surface was more likely to have been sand, or simply packed earth.

Another, more contemporary example, can be found in a garden I designed for a residence in Manhattan, called the Still Point Garden. Although the intentional theme of that garden was the scientific concept of singularity, it can also be said that Shumisen, as a central stabilizing axis point, is also a kind of singularity, and the single standing stone in the Still Point Garden looks uncannily like the Shumisen stones of ancient Japanese gardens. Michiko no Takumi created the first image of Shumisenin a Japanese garden and, in doing so, he initiated an allegorical motif that had incredible longevity, echoing down 1,400 years to our very time.

MARC PETER KEANE is a Kyoto-based landscape architect, garden designer, artist and prolific writer (also KJ contributing editor), whose books include Japanese Garden Design, Japanese Garden Notes: A Visual Guide to Elements and Design, The Japanese Tea Garden, Songs in the Garden: Poetry and Gardens in Ancient Japan, The Art of Setting Stones, Moss: Stories from the Edge of Nature, Of Arcs and Circles: Insights from Japan on Gardens, and Dear Cloud: Letters Home from a Long-distance Traveler. His most recent publication (self-illustrated) is The Name of the Willow. https://www.mpkeane.com

This article appears in KJ 106 (Cultural Fluidity).