This year’s theme, “Source,” a cognate in French and English (in Japanese 源, 始まり“origin,” “beginning”) is, as always, designed to be wide, deep, and open to interpretation. In “Deep Seeing,” his KG+ show at the Take 2 Gallery near City Hall, John Einarsen (founding editor of Kyoto Journal and a longtime supporter of Kyotographie) locates the starting point of photography in the act of momentarily putting aside preoccupations with the self in order to faithfully represent what is seen – and then share this perception with others. His intensely colored works convey the joy that this brings.

Ando Tadao’s Times building

For the past 13 years, co-directors Lucille Reyboz and Nakanishi Yusuke have invited the people of Kyoto – old, established families to tourists just passing through – to engage in a month-long jeu d’esprit inspired by their ecumenical embrace of all aspects of the photographic medium, from crude pinhole cameras to high-powered scientific instruments, and everything else in between. One of the initial attractions for long term residents like me was the chance to pursue the game in heretofore hidden, forbidden, and undiscovered locations throughout the city. In addition to opening up such spaces to the general public, Kyotographie has also reached out to and cultivated new ones, such as the Tambaguchi Wholesale Market and the Kyoto Shimbun’s former printing plant. As the festival has grown in size and substantiality, it has receded into a set of regular locations in the city center, and a set of regularly-featured programs. However, every year there is one new “surprise” venue: this year it is Ando Tadao’s iconic Times Building, which had not been in use for almost ten years.

The energy of Kyotographie’s early “handmade” years has increasingly been flowing into the various KG+, KG Select, and Special exhibitions, numbering more than 100 this year. While the main venues offer visitors the opportunity to interact with “masterpieces,” the satellite exhibitions, which are mainly devoted to local artists and take place in small galleries and newly opened spaces in such varied places as university dormitories, hotel lobbies, pubs, and underpasses, continue to give visitors opportunities to encounter the unexpected.

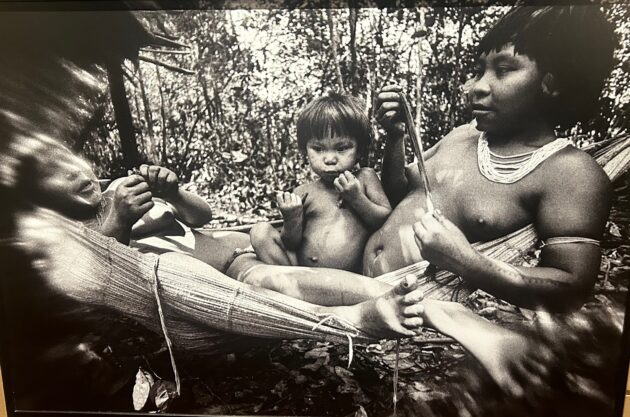

The word “primitive” comes from “primus,” meaning “first,” and “The Yanomani Struggle” in the Museum of Kyoto Annex, resonates with the festival’s theme from the perspective of time. The Swiss-Brazilian photographer, Claudia Andujar, 92 years old, lived in close contact with members of the primitive Yanomami tribe for over fifty years. Since the 1970s, her intimate photographs of the Yanomami, casually naked, lounging, working, playing, and drinking ayahuasca, a psychoactive concoction used for religious and recreational purposes, have provided a window into the early history of humankind. In this exhibition, a small selection of Andujar’s photographs are exhibited alongside drawings contributed by shaman and tribal leader Davi Kopenawa of the Xapiri, invisible spirits that form the basis of Yanomami cosmology. According to Kopenawa, who accompanied the exhibition to Kyoto, “it is important for white people to have something that they can see.” He further explains that the Yanomami had been waiting for a “special white woman” to help them in their continuing struggle against not only illegal ranchers and gold miners, but the general destructive force of “consumer lifestyles.” A larger version of this exhibition, based on the book published by the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in 2020, has traveled around the world, raising awareness of the Yanomami struggle.

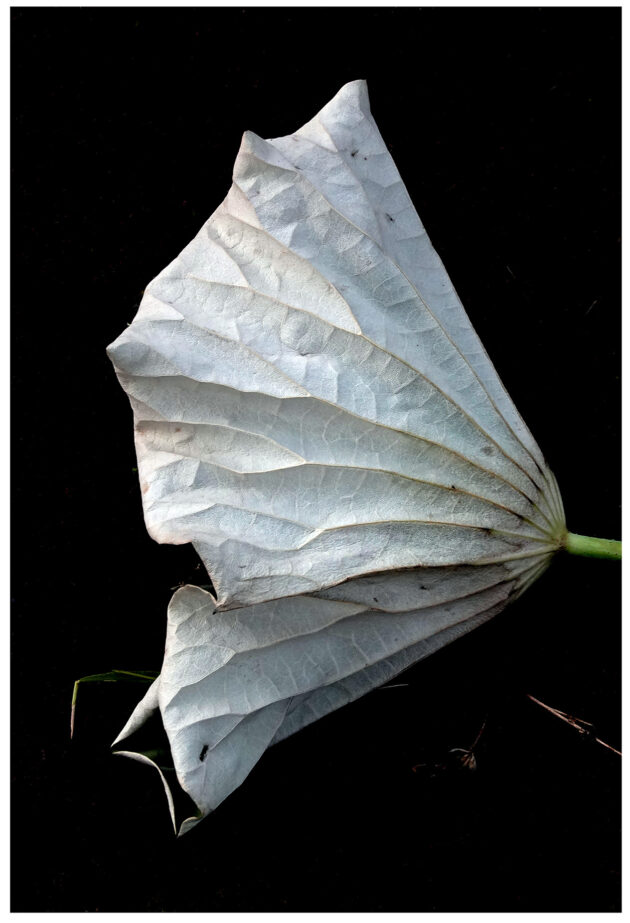

The immense kitchens of Nijo Castle’s Ninomaru Palace are the site of “Seed Stories.” The large, elegantly mounted exhibition features extraordinarily large-scale photographs of seeds taken with scientific equipment as well as glass globes containing actual seeds. Seeds are usually associated with the male role in sexual reproduction, but magnified under Thierry Ardouin’s exacting lens, they suggest female forms as well. He examines a wide variety of seeds, both exotic and local Kyoto seeds, organic and GMO. The flamboyant scientifically tampered-with seeds form an interesting counterpoint to the Yanomami bodies seen in the previous exhibition.

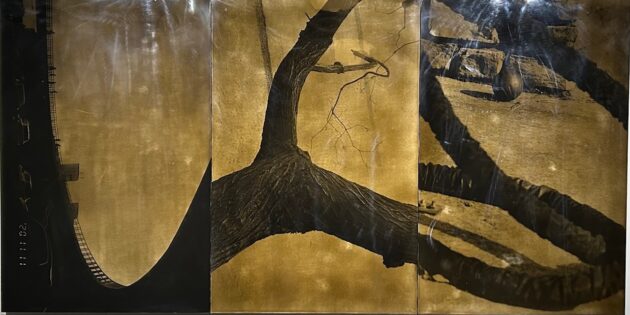

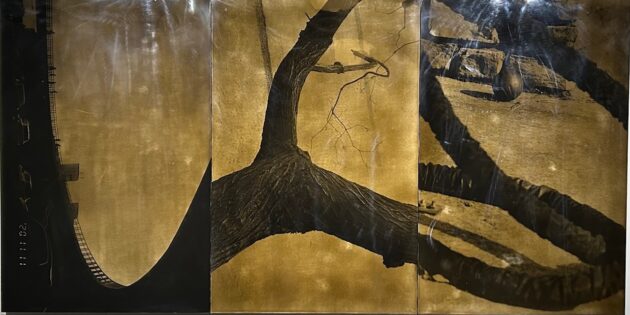

To celebrate their 20th anniversary, Chanel Nexus Hall, one of Kyotographie’s original sponsors, has embarked on a new series promoting the work of Asian photographers. This polished exhibition in Kondaya Genbei, itself one of the festival’s first supporters features the work of the Chinese artistic team, Birdhead (Song Tao and Ji Wengyu) who first rose to fame 20 years ago chronicling the rapid changes in their native Shanghai. For the Kyoto version of “Welcome to Birdhead World, Again,” the long, narrow Chikuin-no-ma is the site of six works from their “Bigger Photos” series. Photo images are screen printed directly onto wood and then treated with a special lacquer finish. The effect is of very old Japanese 屛風/folding screens, which on closer inspection can be seen to be made up of juxtaposed images that are semantically unrelated. “Matrix,” in the room at the end of the corridor, is an intricate collage of 124 photos taken in Tokyo and Kyoto last year. The duo’s name comes from a random word processor keystroke, and this irreverence can be seen in the exhibition in the Kurogura (‘black storehouse”) in the back of the property, which has been transformed into a cathedral dedicated to the new religion whose creed is “We will shoot you.”

The cavernous space underneath the Kyoto Shimbun building, which formerly housed the newspaper’s printing plant, is the site of “PHOSPHOR: Art + Fashion 1990-2023,” a massive retrospective of Viviane Sassen’s work, ranging from her juvenilia and art school graduation photos (which were inspired by Araki’s 冬の旅/Winter Journey) to her recent fashion photography for Dior, the sponsor of the exhibition. Sassen spent three of her early years in Kenya. Revisiting Africa as an adult, she told an interviewer, “[it felt] so much like coming home and at the same time I know I will never be part of that society,” a feeling to which many foreign residents in Japan can undoubtedly relate. The exhibition encompasses a variety of photographic styles, techniques, and embellishments, but it is her quirky treatment of the female body that is most interesting. Known for her goddess-like beauty, the Dutch photographer refrains from appearing in her own works, yet they somehow reflect a beauty’s attitude of not needing to go too far to attract attention.

Ando’s Times building, floating just above the waterline of the Takase Canal, is the site of the exhibition dedicated to the winner of last year’s KG+ exhibition, Indian photographer Jaisingh Nageswaran. Born into the Dalit caste, against the odds he received an education thanks to the strong determination of his grandmother, who started a school in her home. A self-taught photographer, his KG+ exhibition, “The Lodge,” originated from his desire to understand his feelings of both solidarity and discomfort in confrontation with another outcaste community at an annual gathering of transgender people in Villupuram. The current exhibition, “I Feel Like a Fish,” is the result of being locked down with his family during the pandemic. First displayed at the 13th African Photography Biennale, it is a defiant celebration of his family heritage.

African photographers have been an important aspect of Kyotographie from the beginning, and after opening a Permanent Space in the Masugata Shopping Arcade, they established a residency program for African photographers, who work is displayed in the arcade and at the Asphodel Gallery in Gion. This year’s winner, Moroccan photographer Yoriyas (Yassine Alaoui Ismail) became a photographer after his career as a break-dancer ended due to injury. From street dance to street photography, “Casablanca Not the Movie” is alive with a dizzying array of colors, perspectives, and camera angles, accelerated further by the dynamic scenography of Tokyo architects Yokomae et Bouayad, Inc.

Sfera, on the same street in Gion, is the regular venue for exhibitions related to human rights. This year’s exhibition, “You Don’t Die: The Story of Another Iranian Uprising,” documents the massive protest movements that occurred after the death of Mahsa (Jina) Amini in police custody for the crime of not covering her hair properly. The protests, which had extraordinarily widespread support, were brutally repressed. These photographs and videos, which were mainly shot by anonymous citizens on their cellphones, were rigorously fact checked by the editorial staff at le Monde for authenticity in order to serve as lasting testimony to the passions smoldering beneath the surface of Iranian society.

The two exhibitions by Japanese photographers at the Kyoto City Kyocera Museum of Art show a sharp binary gendered contrast. Kawada Kikuji’s “The Map/Visions of the Invisible” is the 91 year-old photographer’s first retrospective in Japan. He first became famous for his series “地図/Map (1959 – 1965). The work of his ongoing long career reveals a restless variety of techniques, media, and printing processes and is displayed in a series of aperture-shaped octagonal rooms.

By way of contrast, “From Our Windows,” the exhibition resulting from the pairing of Kawauchi Rinko and Ushioda Tokuko, is restrained in style and subject matter. Kawauchi, whose images characterized by a muted color palette and focus on the “small mysteries of life” have attracted a wide audience, surprised Kering, the mega holding company of European luxury brands sponsoring the exhibition, with her choice of Ushioda, as her collaborator for this year’s edition of their “Women in Motion” series.

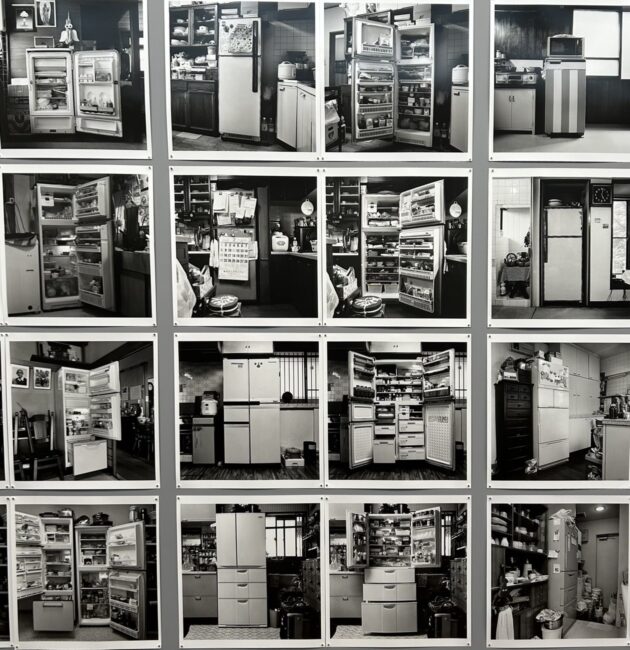

Born in 1940 and a trained photographer, Ushioda only took pictures when her husband and child were out. The photographs in the series “My husband,” a warm and intimate portrait of her life after giving birth and marrying, had lain in a box in her attic for 40 years. The series, ICE BOX is the result of her husband bringing back a second-hand refrigerator, too large for their apartment. She found photographing the inside of her refrigerator “embarrassing,” but for 20 years she continued to shoot the inside and outside her own and her friends’ refrigerators. In the same gallery, several long glass vitrines filled with the detritus of Ushioda’s apartment is further testimony to her compulsion to disclose and share information about her decades of hidden life.

James Mollison points out that having a bedroom, a “personal kingdom,” is an experience that does not apply to much of the world. He began taking the photos that eventually became “Where Children Sleep” while working of a project about children’s rights. In the course of almost 20 years, he has gotten to know and photograph children in 28 countries. He says that Kyotographie’s treatment of the exhibition in the Kyoto Art Center is the best to date, with 35 life-sized full-color photographs, each accompanied by a portrait and a background essay. While children originate from the same place, where they sleep reveals “the reality of their situation” determined by geography, wealth, security, privilege, precarity, homelessness, statelessness, addiction, and religion in fascinating detail.

“Gypsy Tempo” in Shimadai Gallery, exhibits a collection of never-before-seen vintage photographs of the Roma pilgrimage to the church of St. Sara-la-kali in the Camargue region of Provence, near where French photographer Lucien Clergue grew up. The main installation, designed by Yamao Erica, curves around the walls of the gallery, a former Meiji-period sake wholesaler, in a ribbon of bright yellow. In the kura storehouse is a display of album covers, from the career of the Roma guitarist Manitos de Plata, who achieved international fame due to Clergue’s patronage.

Speaking of origins, Clergue is also renowned as a co-founder of Les Recontres d’Arles, the progenitor of Kyotographie. According to legend, in order to give the faltering festival a jump start, Clergue travelled to California to beg Ansel Adams and Edward Weston’s participation. It is amusing to think that two American photographers are at the heart of Kyotographie, where an American presence is otherwise so scarce that it is almost as if the French and Indian War had been won by France.

Los Graciosos perform at Shimadai Gallery

While Kyotographie cannot be said to be on auto-pilot, Reyboz and Nakanishi’s seemingly inexhaustible energy seems to be flowing into their other great passion — music. Last year saw the establishment of the first Kyotophonie Music Festival, which brought an amazingly sophisticated variety of Japanese and international artists to the city of Kyoto in the spring and Amanohashidate in northern Kyoto Prefecture in the autumn. Of course there is a circuit of musical acts as well, but many of those appearing at Kyotophonie were performing in Japan for the first time, and the way in which they are staged and audiences are accommodated makes this a festival that should not be missed – especially in its first few years 😉

Susan Pavloska is KJ’s Senior Editor, and a board member. In her day job she is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Global and Regional Studies at Doshisha University, Kyoto.