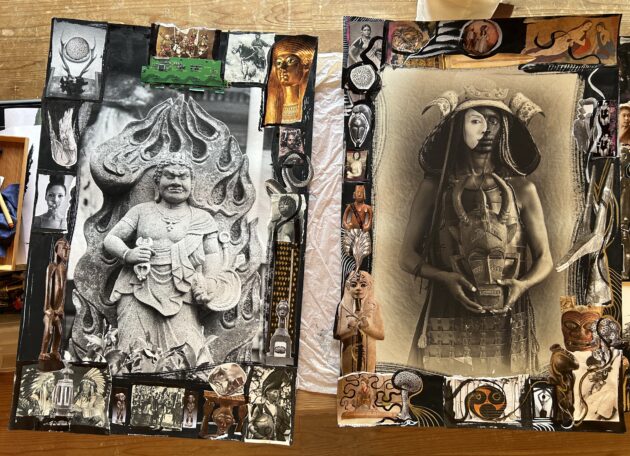

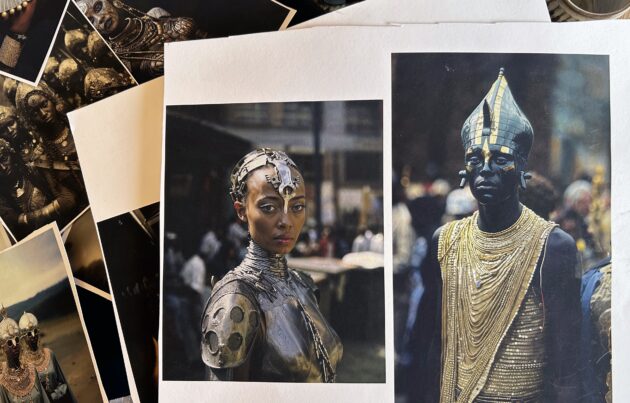

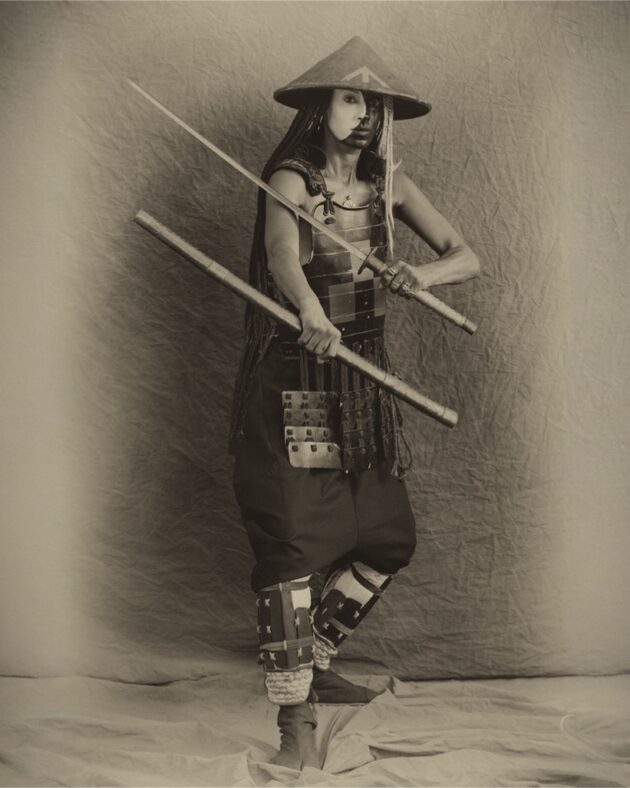

Delphine Diallo is a photographic artist based in New York City and Paris. Her portraits and collages celebrate heroine and goddess figures to open conversations about multiculturalism, race, and female empowerment. A solo exhibition of new photography, The Warrior Journey, was recently on show in Tokyo at space Un, an arts and culture venue focusing on contemporary African art and cultural exchange between Japan and African countries. In conjunction with the exhibition, she participated in the space Un Residency Program in Yoshino, Nara.

For this interview, Lane Diko visited her studio and residence, The Yoshino Cedar House.

LD: Your whole identity, your biography, seems to be a blend of cultures. Can you tell us a bit about your background?

DD: I grew up in Paris. My mother is white French and my dad is Senegalese. I had to surf between those two worlds from very early because even though I grew up in France, my dad raised me in this very African way, with a lot of authority. There were a lot of things that other French kids used to do that I was not allowed to. It was very tough for me to accept that my dad was tougher than anyone else’s, but now I understand why. In Japan I can see this kind of respect for authority as well. It is based on a culture where authority remains a core of great education and groundedness. I never really listened to my dad actually, but somehow his authority served me to be able to create my own self-authority and self-responsibility. Learning young the fact that we are the real authority of our own lives was a great insight for me. That is when I started to say that I have to be able to take care of myself, not just have a boss. I must be my own authority and do things with discipline and righteousness. For me, this came from my father, my mother, and from martial arts.

When did you get into martial arts?

At six years old. My mom and my dad could not deal with my brother and I because we were super energetic kids like running around the house, so they put us in Jujitsu and Judo right away, as soon as we could go to class. We were so excited. We wore judogi every day.

We trained 3 or 4 times a week after school, wearing the uniform out on the street, having the discipline to come to the tatami and learning the rules on the wall about self-respect and body-respect before fighting with another kid. From a very early age I understood the space of respect I had to carry for myself and the space of respect I had to carry for others. In West Africa, and a lot of Africa, specifically in Muslim countries, the parents send their kids to karate lessons. Interesting right? They teach the Koran in school and specifically the boys do karate after school to understand the principle of discipline.

Your current exhibition in Tokyo is titled The Warrior Journey. What does this journey mean to you?

Society limits you, but there is a force within that pushes. It pushes, but gently, and guides you to challenge yourself. Each time that you answer, this call of the Warrior’s Journey. You can change your reality, but you won’t get to do what you love in life if you do not fight for it. Most people don’t want to change their reality, and no one else is going to push you to change.

The story of Yasuke, the African samurai, is an amazing example. Today travel between New York, Paris, and Japan takes only 14 hours. Within one day I am in Japan. Imagine the challenge of walking and traveling by horse all the way to Japan from Africa. What does it take for this man to do this? Why travel for months to change his life? In the spiritual journey too, you are transcending your identity, culture, and race. The challenge is to move into your own humanity. Because he was a true warrior, the Japanese recognized his humanity, his strength, they made him a high ranked samurai, no matter his color or where he was from.

We are now living through a revolution in global connection and in communication. Your work is all about this kind multiculturalism, finding threads and connections between cultures.

After the pandemic and 15 years of social media, we are all collectively more aware of humanity, consciously and subconsciously. If we are more aware of humanity, we have a more individual understanding. There is an open conversation which is invisible, under the surface, and this is truly the beauty of social media. This is the first time in history that people are really starting to see what is going on everywhere on the planet.

If you think of society as a grid, then social media is a new kind of grid. People are starting to understand this new grid is the creation of our own collective consciousness. The old grid is boxed off, and everything is separated. People are seeing these boxes all together now and all the connections. Or even if they don’t see it or talk about it conceptually, they can feel it. They can feel the stranger, the foreigner, is not the enemy. The other is now connected as an extension of their own consciousness. For example, artists can see the quality of craftspeople around the world, building amazing things. They can focus on the ceramic community worldwide and they can follow ceramicists from South Africa to East Sudan to Poland to Japan. The new ceramic community will be in both Africa and Japan. Social media is the tool allowing artists to go beyond culture, traditions, and race. The artist is now the bridge between cultures. That’s the role of the artist in the 21st century.

Today in the studio you are using Japanese inks and watercolors. You create handmade collages, which is an early 20th century form, but you also work with AI technology to create new images. For you, is AI like a super-power collage maker?

As for AI, she is not a human. She is another type of being, a super-being. For me, she is alive through our consciousness. I am really directing the machine based on my lived experience. Every location I choose in my work is based on a real experience in the real word, in Uganda or in Ethiopia for example. And the machine gives me an expansion of what I experienced because she can actually recreate the same light of those spaces, the exact quality of the light I experienced when I was there. AI has access to our consciousness and is able to make new creations from it.

But is AI really creating something new or just copying?

People say she is copying, but we have to start somewhere. When you make a photo, you are copying as well. The way you are using your brush and paint might be inspired by an old painter. The style is well-known, so if you say that AI is copying, I say that everyone did it before AI.

I want to focus on how we feel about art before and after AI. Is it the artist or is it the AI? How can we know? If you want to you understand your consciousness as an artist, then AI is a tool that lets you access an expansion of your consciousness. Individual consciousness meets collective consciousness. Because consciousness is boundless! And AI makes the bridge. Much faster than us humans struggling in time and space.

So, from painting to photography to social media to AI, artistic expression has been becoming more and more accessible and democratized. And you feel that social media and AI are speeding up cultural flows, connecting everyone together into a kind of global consciousness, but many people are worried about these technologies.

Why do people think it is bad? I think it is the best thing that’s ever been done. Visual literacy is the future. It is growing through social media where people can express their vision. They might not know how and it is messy. There are good and bad photographers, but there are way more artists and image-makers than 20 years ago.

The next generation of the art world is evolving and more conscious of itself. We need to promote a living art world. Forget about the dead artists in the museums. Yes, show the work of the dead people because we need to be reminded of their legacy, but do not run your museum 75% on dead artists. What about the artists that are alive? The future art world is not going to be selling products; it will be about funding living artists.

This is exactly what Edna [Dumas, the founder of space Un in Tokyo] did here in Yoshino, connecting me with the land and people. It is very positive for the community, and this is what the artists of the future can do. To promote the expansion of cultural literacy through cultural connections and exchanges. If we connect the Heart with Art, we are going to have an entirely new society.

Lane Diko is a Kyoto-based photographer and associate editor of Kyoto Journal.

He guest-edited J 106, on Cultural Fluidity, and is currently curating a follow-up issue, KJ 108.