So gorgeous

The poison mushroom

—Issa

[I]n Japanese, the general word for mushroom, kinoko, means “child of the tree.” Names of species then reflect specific trees plus the suffix –take (or dake), signifying “mushroom.” Thus, the long, white and delicate enokitake, relished in clear soups in Japan, means “hackberry tree mushroom.” But this only tells part of the story, since Japanese mushrooms can also derive their names from characters in folklore, animals, colors, modes of life, or even utensils they may resemble. Although names certainly provide insight into the emphases of a given culture, the mushrooms themselves are universal and elude fixed boundaries.

Within the standard biological division of higher organisms into two distinct kingdoms — plants and animals — mushrooms fall somewhere in between. Although these fungi grow in one spot and resemble plants, unlike their chlorophyll-containing relatives, mushrooms cannot produce their own food. This distinction draws them closer to animals, who must also find external sources of nutrition to survive. Neither are the cell walls of mushrooms fortified with cellulose as in plants; instead they are made of chitin, the same material that forms an insect’s exoskeleton. Plants produce oxygen, but mushrooms release large amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere as they decompose dead plants and animals, or attack living ones. Yet often enough, mushrooms also form mutually beneficial partnerships — matsutake with red pine, or black pine with hatsutake. Astonishingly, fungi are unlike either plants and animals in that they possess over a hundred sexes and hence break with the familiar biological binary of male and female.

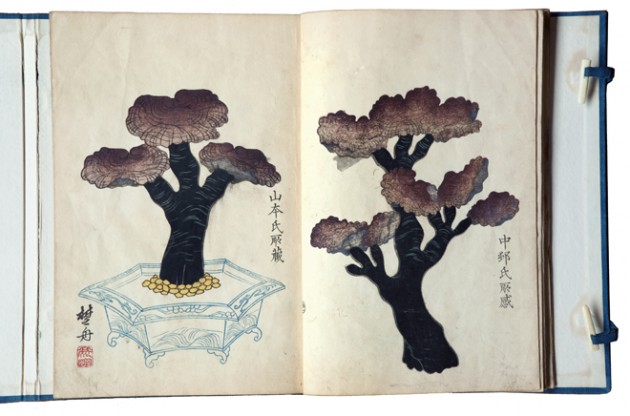

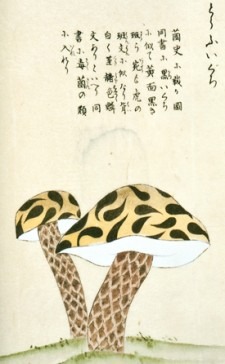

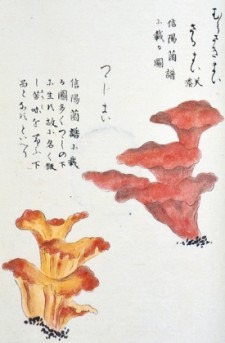

The ambiguous and maverick nature of mushrooms accounts at least partly for their perennial association with mystery. They appear in the world somewhere between life and death, plant and animal, medicine and poison, shadow and light, and male and female. Their fleshy bodies emerge in the dark, thrive half-hidden under leaves, grow from dead tree stumps on forest floors, or high aboveground on living trunks. They materialize low amidst rot or turd, arrayed in arcs, rings, or erotically solo. What catches the eye — the mushroom — is actually only the transient fruit of a much larger organism hidden under the soil. Above or below the ground, mushrooms can produce savage odors. The stinkhorn’s stench simulates carrion to attract flies who in turn carry off its spores, and the earthy truffle produces a scent so rich in sexual suggestion that sows mistake it for the male pig and root it greedily from the ground. Mushrooms come in colors vivid or somber, and some even glow the yellow-green of fireflies at night. Others entice through an eccentricity of form: parasols, starbursts, white nets that hang to the earth, or what appear to be UFO launching pads.

Over millennia, mushrooms have inspired rumor, endless supposition, and even deep religious devotion. While ancient peoples in the Western world often thought them the offspring of thunderbolts, in recent decades their mystique has generated more elaborate theories. According to one, certain psychotropic species are thought to have entered the early primate diet and been the actual cause of human language through a synesthesia that allowed the linkage of sound with mental pictures. Christianity too has been attributed to fungal origins, with the holy Eucharist interpreted as an actual code for the ritual consumption of Amanita muscaria. Even jolly Santa in signature red and white with flying reindeer is thought another code for the Amanita cult. After all, the mushrooms were fed to reindeer to draw out poison before the participants quaffed the animal’s urine. Wall Street banker and mushroom explorer Gordon Wasson went so far as to categorize the world’s cultures as “mycophilic” and “mycophobic” — cultures that either love or feel repelled by mushrooms. While the mushroom scene in Anna Karenina won Russians a permanent place among mycophiles, the Anglo-Saxon’s frequent association of fungi with decay and rottenness (from Keats to Emily Dickinson) led Wasson to dub them mycophobes.

Be that as it may, Wasson was certainly correct in ranking Japan as one of the world’s most mycophilic civilizations. From Okinawan sub-tropical forests to arboreal Hokkaido, the Japanese archipelago supports a rich variety of fungal life. The Japanese were the first to cultivate several species now widely used commercially: maitake, namekodake, and enokitake. Pioneer mycologist Mori Kisaku who founded the Mushroom Park in Kiryu (Gunma pref.), developed a unique and reliable cultivation method for shiitake by using slashed logs of shii (an evergreen oak) and cork plugs impregnated with the spawn. He based this method on his discovery that shiitake appeared along Japan’s typhoon belt that crosses parts of Kyushu, Shikoku, and Shizuoka. Mori’s method rescued local communities in Kyushu from economic ruin and earned him the status of a local saint. A statue dedicated to him in Oita called “Naba Kannon” (Avalokitesvara of the Mushrooms) shows the bodhisattva of compassion surrounded by hundreds of shiitake.

Maverick genius and polymath Minakata Kumagusu remained a mushroom devotee throughout his life. For fourteen years, Minakata traveled as far afield as Michigan and Cuba in search of fungi. Although he returned to his homeland in rags, he carried with him a treasure of some 140,000 specimens.

Novelist Tanizaki Junichiro once defined the Japanese aesthetic as one that privileges darkness and finds beauty “not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against the other creates.” Tanizaki’s words are suggestive of the natural habitat of mushrooms. Hence, it is not surprising that from the mushroom haiku of Basho and Issa, to contemporary artistic expressions, the mycophilic tradition has persisted in Japan. Fashion designer Tsumori Chisato incorporates mushroom motifs in her fabrics. Founder of the superflat postmodern art movement Murakami Takashi masterfully captures the innocence and seductiveness of fungi in his “7-Panel Mushroom Painting” in which psychedelic-colored mushrooms are dotted with long-lashed cartoon eyes. Japan’s most popular mobile phone company — DoCoMo — adopted a mushroom as its mascot. Docomodake is a goofy but loveable representative of kawaii or “cuteness,” and renders the company friendly and approachable to the customer. The eight-volume manga series by Ishikawa Masayuki — Moyashimon: Tales of Agriculture — is the story of Sawaki Tadayasu, son of a sake brewer who has a peculiar gift: He can see and communicate with bacteria and fungi.

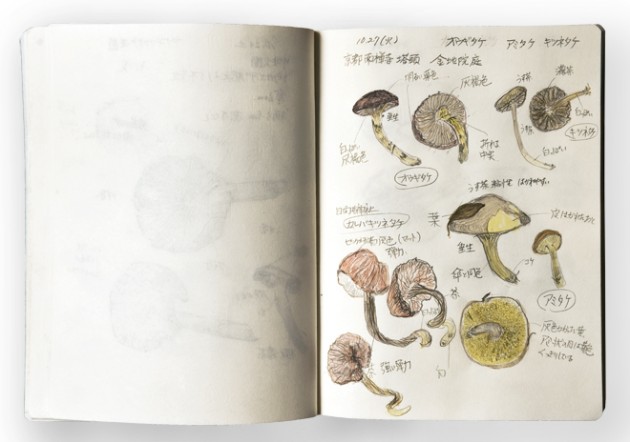

Even in mycophilic Japan, however, mycology remains one of the least researched fields among the sciences. In recent years, the number of professional mycologists has dwindled while amateur mycologists have assumed a new and important role. To date, some 12,000 mushroom species have been described in Japan, but less than half include “voucher specimens.” Without accompanying material proof to validate these descriptions, mycology cannot move forward as a science. Amateurs are now collaborators in this gathering of samples and are vital to the progress of the science of mycology in Japan. Aside from professional organizations such as the National Mycological Society of Japan, regional and local mushroom clubs are common across the country. The Kyoto group alone attracts 50 to 100 men, women and children to its monthly walks through the spacious park that surrounds Kyoto’s ancient Imperial Palace.

In a country where it is often said that “the nail that sticks up gets hammered down,” a paradoxical appreciation has long thrived for those who do escape the usual boundaries. Mushrooms are mavericks and enjoy an iconic status in Japan.

I would like to thank the following mycologists for generously sharing their professional expertise with me: Ando Katsuhiko of NITE Biotechnology Development Center, Hosoya Tsuyoshi of the National Museum of Nature and Science, and Neda Hitoshi and Hattori Tsutomu of the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute.