Leath Tonino

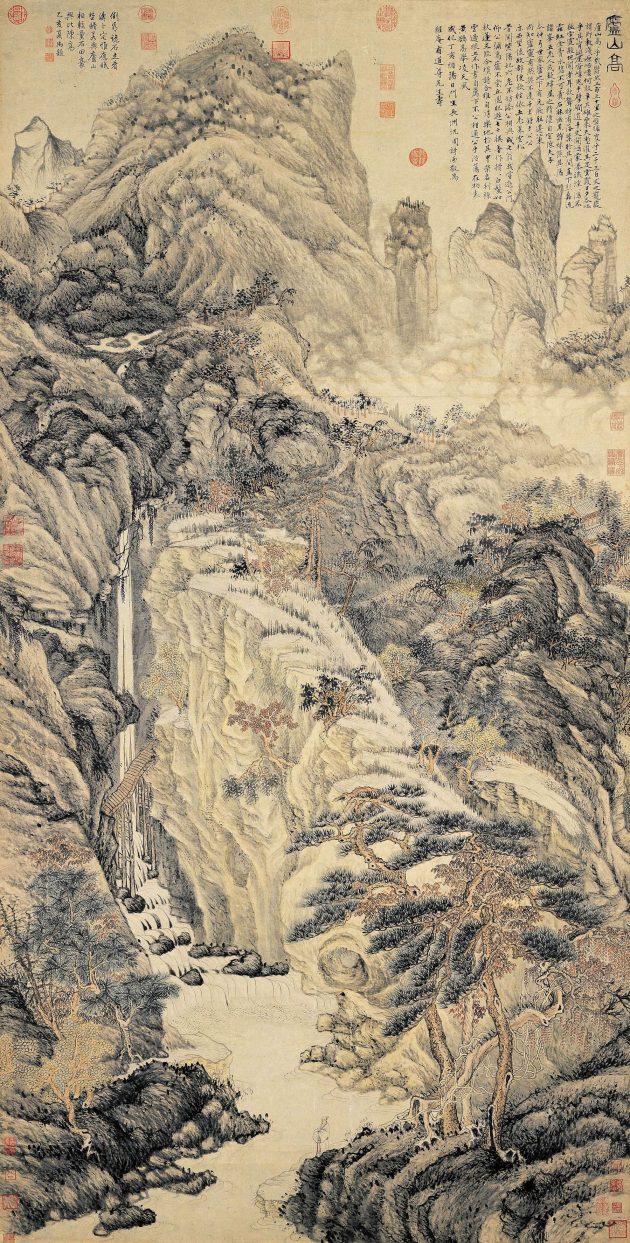

When I moved to San Francisco, in my early twenties, I got my ass handed to me. Not only was I a newbie in the big bad city, I was also fresh from the woods, from a six-month stint tracking raptors as a US Forest Service biological science technician. Don’t be misled by that dry title, the work was all wonder and delight, all vast humming stillness at sunup and sundown. I loved it dearly: the long mornings bushwhacking, the long evenings sprawled on my cabin’s crooked deck with a banjo and sky of drifting clouds. But dwelling in an isolated one-room hermitage—picture the stereotypical Chinese landscape painting, some tiny dude plucking a zither down in the corner, his snug shelter surrounded by pines and cliffs—well, this had done nothing whatsoever to prepare innocent outdoorsy me for the suffering that is so relentlessly everywhere on our nation’s streets.

Those streets, my goodness, those pinched gray streets! Those streets of wind-strewn trash and fog-wetted grime! Those streets of siren-wail and human-whimper! With half a year’s pay in my pocket and no desire to get a so-called “real job,” I quickly fell into the habit of strolling to the public library, exploring en route the labyrinth of concrete and grief. Some folks commute by car, tinted windows shading and shielding away the unfairness of this world: broken shopping carts brimming with broken junk, broken bodies limping through broken lives. Other folks—seasonally unemployed naturalists trained to pay close attention to their surroundings, for instance—tiptoe past bearded men sleeping in cardboard beds, try not to weep at the sound of some teenage girl’s weeping, and just gaze dumbly, helplessly, when asked beneath an overpass, through a chain-link fence, “Please, sir, can you find my spaceship?”

The first day I made this journey, vanilla scent of pine bark still fresh in my nose, mingling there—or perhaps doing olfactory battle there—with tang of sewage, funk of grease, and staleness of spilled beer, I immediately sought out a haven in the stacks, a spot to recreate the calm of my backcountry cabin. By chance, the quiet nook I found was the Chinese Center: a circular room with red carpeting, clean wooden tables, books galore, and a cute old man wearing incredibly thick glasses. He was hunched over a text that I could not decipher, flipping pages with a gentle touch, easing them down as though each were delicate, precious, deserving of total focus. You’ll protect innocent outdoorsy me from this too-fierce metropolis, I thought, settling into a nearby chair, breathing deep, won’t you?

Not exactly. Turns out the library—warm, dry, offering public lavatories—was just a tad less chaotic and desperate and in-your-face than the pinched gray streets. Over the coming days and weeks I encountered, right there in my refuge, a steady stream of yelps, fights, blank-eyed stares, stolen phones, semi-covert drug deals, billyclubs hidden in coats, psychotic rants about Nazis and Jesus and baseball. Despite its sturdy stone walls, the library was in fact a flimsy membrane, a permeable cell. For every cute old man wearing incredibly thick glasses there were a couple dozen folks who had been, and would continue to be, brutalized by their wanderings in the labyrinth of concrete and grief.

Nonetheless, the Chinese Center remained my special retreat for the duration of that cold, wet, shocking San Franciscan winter, and here’s why: landscape paintings. Paintings of cozy huts in enveloping wilderness, of tiny dudes cradling zithers in their arms, of peace amidst inky trees and pale washes of cliff. Paintings suffused with the easy, welcoming, flung-wide spirit of Buddhism, or Taoism, at its best, a spirit less spoken than seen, inarticulate yet instantly recognizable in smooth lakes and coiling mists and empty valleys. Paintings that reflect, I’m tempted to say, the secret topography of some brush-wielding recluse’s enlightened heart-mind—a nature both outside and in.

Most mornings, having peed in the crowded Men’s Room, ascended three flights of stairs, and flashed my kindest smile to the ragged fellow who “guarded” the Chinese Center with his manic pacing, I would grab a random volume from the shelf and take a 15-minute tour through the countryside, images of fishermen on riverbanks and woodcutters on narrow mountain trails soothing my sidewalk-frazzled nerves. The captions were incomprehensible to me, which means I never read about the paintings that fanned through my consciousness—never learned names and dates, the evolution of the artistic tradition, or what role it played in the religion of the era. I looked, that’s all. I entered those environments—cast my line with the fishermen, hiked alongside the woodcutters—and in doing so revisited my own special place: the cabin, the crooked deck, the sky of drifting clouds.

****

In an essay from The Great Clod: Notes and Memoirs on Nature and History in East Asia, Gary Snyder characterizes the landscapes of Sung dynasty painting as “numinous and remote,” but in the very next sentence he adds that “they could be walked.” This dynamic—a faraway realm of sacred serenity, then an immersion into visceral terrain—resonates with my experience in the Chinese Center. Snyder goes on: “Studying Fan K’uan’s ‘Travellers Among Streams and Mountains’… one can discern a possible climbing route up the chimneys to the left of the waterfall.” Indeed, the paintings I viewed were portals, passageways, invitations to wander and explore. As with the hand-drawn maps at the start of every fantasy novel I read as a kid, their intricate details helped me to temporarily lose myself.

Which leads to questions. Was I avoiding the suffering of our time by disappearing into pretty pictures? Was I running and hiding, putting my head in the paint as an ostrich puts its head in the sand? Was this my version of the tinted window, of commuting by car, of retreating from our everyday nightmare—the prostitution and opiates and unfathomable poverty? I don’t think so. If the goal was denial, escapism, I wouldn’t have exposed myself each morning—step after step after step, no earbuds, no pricey coffee-treats bought as distraction—to those pinched gray streets. Instead, I would have hunkered in my apartment with the blinds drawn, brooding about the wondrous cabin I had left behind and the dismal new habitat that had replaced it. Looking back, it’s clear that I was trying to get some perspective, trying to see the world for what it really is: homelessness and at-homeness, grit and dewdrops, cardboard beds and woodland birds. I was trying to apprehend a few of this world’s many facets and reconcile them within my own heart-mind. In short, I was trying for a kind of balance.

And isn’t that, at least in part, what meditation and art and nature are all about? Neither the cushion, the gallery, nor the secluded grove can be for us an everything, a site of permanent relief. We can visit these pockets of breath and beauty, though, can visit them regularly, as a practice, that we might find the resolve to face what needs facing: the gaunt faces lost in cigarette smoke, the pale faces sliding from their bones. Author Barry Lopez, who has extensively explored both the wilds of the city and the wilds of the land, says in an interview, “If you have the Bach cello suites in your head at the same moment that you’re looking at a gas chamber at Auschwitz, then to me you’ve got some hope of being fully aware of what it is that we’re enmeshed in…. There’s something captured in [the cello suites], and that is the fuel that you use to open yourself up to everything else….”

Cello suites. Chinese landscapes. An audience of ten thousand hushed conifers, the banjo’s strings silky against my fingertips. Therapist friends tell me that a common instruction for people undergoing some form of emotional anxiety is to envision a quiet, safe place from the past—Grandma’s living room, say, or a one-room hermitage in the National Forest. Be there. Inhale and exhale. Relax. It’s not wrong to visit such memories, to counterbalance the incredible weight of existence with their incredible lightness. To the contrary, there are few things more proper, more necessary.

As the winter progressed—as the soles of my sneakers wore away from the pounding of 100 walks, from countless hours beating those pinched gray streets—I found myself returning to a little prayer, a little dream. Like the flung-wide spirit of Buddhism, it was nonlinguistic, inarticulate, more a surging empathy than a recitable poem. If I were to translate it, I suppose the words might go something like the following: How I wish, how I wish, how I wish. How I wish for my people, these weeping teenage girls, these earnest spaceship men, how I wish for them a cabin in the pines. How I wish for them a sanctuary in the woods, in themselves, in a painting, anywhere. Maybe they once had a cabin? Maybe they’ve seen their cabin burn? Maybe they’ve seen it turn to ash? How I wish for them a path back to the tranquil place, the soft place. How I wish they could lie down beneath the sky of drifting clouds and play the innocent game, the childhood game, of waiting on the night’s first star. How I wish they, we, all of us could play this game, play it together.

Alas, my genuine concern over urban suffering, without a link to tangible action, failed to have an impact. The season slowly turned. San Francisco slowly became my home. That a lump in the throat is merely a lump in the throat—this was, perhaps, the second way that the metropolis handed me my ass.

So it goes. I kept walking, kept watching, kept up my practice. And then, in the Chinese Center one stormy spring morning, a book of physical and more-than-physical landscapes in my lap, I noticed a guy: huge backpack, ratty jacket, rotten teeth, brain on fire with demons, on ice with angels. He was young, around my age, and familiar. I had observed him at least a dozen times in the labyrinth of concrete and grief. Observed him on the library steps and the gusty corner and the filthy curb and the benches beside overflowing garbage bins. Observed him twitching and jerking and dancing his pain to an accompaniment of sirens and whimpers. This day, however, he was stilled, hunched over a giant book, peering into a wilderness of trees and cliffs and secret huts.

Familiar? Yes, he was familiar. Thin. Blonde hair and a scraggly beard. Blue eyes. He looked—it was staggering, really—very much like me.

A few minutes later, when the page flipped—not the page in my lap but the page in his—it was with a gentle touch, a touch reminiscent of that cute old man wearing incredibly thick glasses, that sage I’d turned to for protection on my first day in the big bad city. Brain flaming with demons, iced with angels: my look-alike set it down as though it were delicate, precious, deserving of total focus. And he was right.

Leath Tonino is a freelance writer. The Animal One Thousand Miles Long, a collection of his essays about the outdoors, will be published this September. Raised in Vermont, he has also spent time working in Arizona as a biologist, New Jersey as a farmer, California as a carpenter, and Antarctica as a snow shoveler.

Image: Hanging scroll “Lofty Mount Lu” by Ming Dynasty painter Shen Zhou. Source: National Library of China