SOMETIMES A NEW LIFE AND A NEW YEAR open on the same page. So it was that I met my in-laws for the first time on New Year’s Day 1966, shortly before my wedding. Tsuneo and I had just come down from Tokyo, where he met me at Haneda Airport, and we were now in a taxi riding through Osaka on the last leg of the journey. As Tsuneo lit up a cigarette, he took the opportunity to remind me that I was not to smoke in front of his parents. This only made me more nervous than I already was. How could I face their scrutiny and appraisal without my trusty Marlboros?

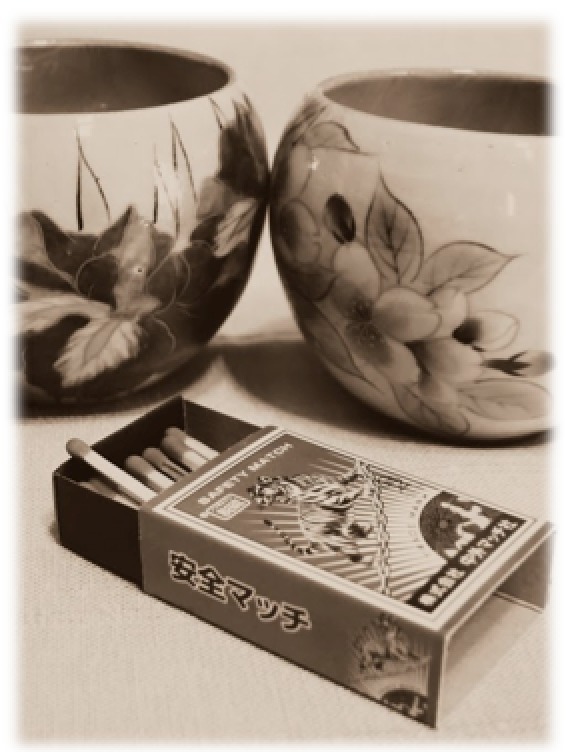

Needless to say, I smoked myself silly during the cab ride and must have smelled like an ashtray by the time we arrived at the family home. After a ceremony of bows and warm greetings, we were seated at the kotatsu*, which held a basket of mandarin oranges, a pot of green tea and, of all things, an ashtray. While Okasan busied herself in the kitchen, Otosan came to sit with us. And the first thing he did was offer me a cigarette. I glanced over at Tsuneo, hoping for a nod of approval, and to my relief soon the three of us were happily wreathed in the pungent haze of Hope cigarettes. And I couldn’t help thinking that Hope was a pretty auspicious way to begin a lifelong relationship.

The next morning I had my picture taken in Okasan’s wedding kimono. After they released me from the layers of silk brocade I changed back into a winter dress, and we left by train for Kobe to complete the arrangements for our own wedding and reception. Despite my being a bride who overslept and then almost lost her veil in the icy winds blowing off Mt. Rokko, the day’s events went well. Hope did not fail us, and over the years, as hope became reality, a loving and enriching relationship developed between us and my husband’s parents. We were able to share many good times together, probably because we never had to live under the same roof.

My in-laws remained strong and healthy and managed well on their own until ten years ago when, with both in their nineties, we all had to face the sad truth that they needed professional help. After some frantic searching, we found for them the new and very well managed Sun-Life Care House about 15 minutes from where we live, and resettled them smoothly. Although Otosan was not at all reconciled to leaving his beloved garden, Okasan was relieved to relinquish the day-to-day tasks of homemaking.

FOR OTOSAN, THE BODY’S DECLINE WAS ENTIRELY NEW TERRITORY; after a lifetime of almost perfect health this robust man took it as a personal betrayal, one that made his final years a time of angry silence. His wife of six decades chided him for his inability — she called it his unwillingness — to meet the trials of ageing more gracefully. He became gruff with the care-home staff, and even stopped talking to visiting family members. Tsuneo and I never took it personally and neither did his dear 97-year-old brother who came to see him all the way from Gunma prefecture.

Otosan passed away peacefully at the age of 102, and after the funeral and cremation, we stored his ashes in an urn on a shelf in Okasan’s room. This past December, Okasan too left us, at 101. And after her funeral and cremation, we were going to have both of them buried together in the family grave in Shiga prefecture. Tsuneo wrote to the head priest of the village temple to make the necessary arrangements and was quite shocked to get a reply saying that unless we had a designated family member living in the area who would take care of the graves, no further burials would be allowed. Since there was no such person available, it was clear that we would have to find another solution.

We brought the problem to our dear friend Father Yano, who came up with an excellent suggestion. It seems there is a temple in south Osaka called Isshinji, where they take in ashes from whomever, and place the urns on a special altar surrounded by prayers and incense. There is a one-time payment of 15,000 yen per urn. Then, at ten-year intervals, the accumulated ashes are mixed together with clay and made into a lovely Goddess of Mercy. When a new statue is to be dedicated, the family members are notified and invited to join in the ceremony. It seemed a wonderful way to be remembered, and fortunately all our family members agreed. Although Isshinji has been offering this service since before the Meiji period (1868-1912), no one we asked had ever heard of it. I somehow love the fact that it was a Catholic priest who put us on to it.

We kept the urns at our house till after New Year’s, and on January 4th, we were to bring them to Isshinji. But first we had to find a compact and tastefully unobtrusive way to carry them in public. And the only thing we had big enough to fit two urns was an old Lego box in splashy reds and blues that was left in our closet. We got it all nicely tied up so no one would ever guess what was inside. It could have been a gift for our grandchildren.

Tsuneo had to take care of some legal business that morning, and left for Osaka ahead of me. I was to follow later, bringing the “package.” And so, it came to pass that forty-seven years after that first meeting with my in-laws over green tea and Hope cigarettes, I was hurrying through our local JR station toting their ashes in a box intended for toys.

Isshinji proved to be old, beautiful and well organized. We signed in, waited until we were ushered into the main sanctuary for a brief service, and then were finally led to the altar where the urns would be stored.

We felt both relieved and grateful to have found a proper and blessed resting place for our dear parents. In our own case, we’ve asked the children to cast our remains on the waters off Hawaii. On second thought, I’m sure we wouldn’t mind being part of a statue in some temple, church or shrine, smiling down on all the people who might come to pray, offer us incense, and now and then, a flower or two.

Ashes to Ashes is an excerpted chapter from Winnie Inui’s forthcoming memoir, Belongings.

Photography by Stewart Wachs