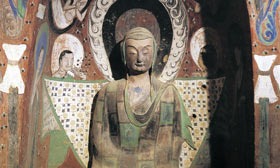

In front of us stood a statue of Buddha, about three meters high, surrounded by swirling painted blues and reds and browns — flanked by two smaller statues of guardians. The light from the open doorway fell on the Buddha and suffused throughout the space. As our eyes moved upward to the ceiling, angled inward from all four sides, we were met with the menacing image of an asura, a wrathful, demon spirit. Around him rose flame-flowing shapes of blue and ochre and beige, interspersed with animal-like figures, all brushed onto the plaster-white surface. On the other ceiling panels was a profusion of characters and forms in various shades: hunting scenes and acrobats and apsara, the flying spirits symbolic of this place. Along the side walls were small images of Buddha, repeated hundreds of times in colorful symmetry. We stood transfixed between the roiling and riotous ceiling and the orderly proportions of the multihued walls.

This was just one (No. 249) of the hundreds of caves, filled with extraordinary Buddhist paintings and sculpture, in the Mogao grottoes of Dunhuang. Words cannot come close to describing the energy and color and beauty of this artwork. The earliest cave, painstakingly carved out of a sandstone cliff, dates to the 5th century. The time of most intense artistic production was the Tang Dynasty (ca. 7th – 10th centuries). Some of the caves were refurbished at the start of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) but the place faded from historical view, and started to slip beneath the sands of the Gobi desert as the nineteenth century turned to the twentieth.

Today, Dunhuang is a major tourist destination, especially popular with Japanese, Koreans and Southeast Asians. It is a highlight of any contemporary Silk Road journey. Carefully managed as a World Heritage Site, the Mogao Caves can only be accessed by groups led by local guides. No lonely backpackers here. Indeed, concerns about preservation will soon limit entrance to the caves themselves; the immediate experience of standing in intimate proximity to the ancient painting and sculpture will be replaced by a video simulacrum.

No such limitations seem to constrain another of China’s Silk Road spectacles: the terra-cotta warriors of emperor Qinshi Huangdi on the outskirts of Xian. Their main pavilion, reminiscent of an airplane hangar, stretches expansively across a grim tableau of brown clay men, arrayed in military ranks, emerging from the depths. Those in front stand in cleared trenches, freed head to foot from their earthly graves. Those further back are exposed only from the waist; while the rear orders disappear beneath the hard packed soil. Hundreds and hundreds of tourists, groups and individuals, foreigners and Chinese, stream through the viewing areas, looking down and across the wide scene. The scale is immense, designed by the first emperor himself to instill fear, the shock and awe of his age.

The terra-cotta soldiers are better known, at least among Americans, but the caves of Dunhuang are more worthy of our attention.

The Mogao caves are sublime expressions of the abiding devotion of thousands upon thousands of Buddhist monks and believers who meticulously created works of transcendent beauty. The paintings and statues have served pedagogical purposes, initiating the illiterate into the intricate stories of Buddha and his followers. While there is a political aspect — religious knowledge and status confer a certain power — what is most remarkable is the sheer splendor of it all: the graceful lines of the sculpted figures, the blazing colors, the ethereal flying spirits, all packed into rough-hewn caves.

Qin’s underground army is another matter altogether. It was his ultimate attempt to maintain political power. He mobilized an entire society for war-making, going so far as to demand that craftsmen build a military contingent that would secure his authority in the afterlife. The terra-cotta soldiers are a massive expression of a megalomaniac’s belief in his own supremacy. Although the tour guides correctly point out that each bleak figure is unique, it is also true that the creative imaginations of untold artists were stunted and narrowed to the task of serving the tyrant. Beauty was sacrificed to power.

The subordination of art to politics is also evident in another corner of Xian, a city that bills itself as the starting point of the Silk Road. When I visited the Shaanxi Provincial History Museum three years ago, I was drawn to their collection of Zhou bronzes (ca. 1000 – 800 BCE). The display was filled with finely cast and crafted wine cups and tripods and bells. When I reached the end of the long case of lovely pieces, I turned to look for the next part of the permanent exhibit and there, across the hall, was an arrangement of flat, crude pots and cups huddled up against an array of weaponry. It was Qin, the time when all art was turned to the purposes of the ruler. The contrast was stark: the aspiration of Zhou versus the instrumentalism of Qin. At that moment I wanted to return to Dunhuang.

History has treated both Qin and Dunhuang unkindly. The first emperor paid a price for his despotism. His dynasty hardly outlived him because of his extraordinary brutality. The people rose up against his son and almost destroyed a portion of his subterranean phalanx. To this day, for many Chinese intellectuals, Qin stands as a symbol of excessive power and cruelty, his archaeological artifacts a constant reminder of his self-centeredness.

Dunhuang was pulled out of historical obscurity by Western adventurers. Most infamously, in 1907 Aurel Stein bribed a local Taoist priest and carted off crates-full of manuscripts and paintings and ceramics. He had seized what turned out to be the world’s oldest printed book, a copy of the Diamond Sutra dating from the Tang Dynasty. It is remembered in China as an imperialist pilfer that rankles national pride. But however violent and dangerous subsequent Chinese experience became — civil war, Japanese invasion, revolution — the art of Dunhuang sat silently in its desert oasis, largely untouched by the human tragedies exploding around it. During the Cultural Revolution, Premier Zhou Enlai dispatched a company of soldiers to protect the caves from the depredations of the Red Guards. It was a reversal of Qin’s method: marshalling coercive power to save artistic beauty.

The apsara of Mogao and the soldiers of Xian remind us of the disparate purposes of the Silk Road. Dunhuang is an oasis crossroads. A place where pilgrims stopped and stayed and were drawn to beauty, the spectacular possibilities of color and line and form. Cultures mixed freely and faith blossomed. The road brought people closer to nirvana. Conversely, Qin’s soldiers are emblems of power. They stand, now frozen and mute and impotent, as symbols of the maneuver and noise and force of military assault. When armies, from the Han to the Mongols to the Qing, set out for conquest, the Silk Road was their route. Thus, the thin track that heads off into the desert has enabled ferocious warfare and religious devotion to coincide in space and time.

By comparison, Dunhuang is the more attractive and valuable relic. The art is obviously superior. And its mere presence is auspicious. The bloody twentieth century, and the terrorized twenty-first, seem to be more conducive to Qin’s ways. Extensive military forces have been institutionalized in many countries. Nuclear weapons are sought after as signs of national prowess. Metal detectors have popped up in all sorts of places, scanning us for threats of violence. But somehow, in this anxious world, the redemptive power of beauty clings to life on the edge of the desert.

If you find yourself on the China portions of the Silk Road, go to Dunhuang. Go soon, while you can still walk into the caves.

SAM CRANE is the Fred Greene Third Century Professor of Political Science at Williams College, where he teaches modern Chinese politics and ancient Chinese philosophy. His most recent book, Aidan’s Way, is a Taoist reflection on his son’s profound disability. Currently, he is working on a book that applies ideas drawn from classical Confucian and Taoist texts to contemporary American social and ethical issues.

Copyright held by the author