Grandma inhaled the fresh air saying our backyard was like “gokuraku,” the place after death where everything has the fragrance of flowers. She lived with us in north Seattle surrounded by blossoms whose buds popped open in the spring, surrounding us in jasmine, lavender, and towering rhododendrons with blooms the size of honeydew. But what I loved most was our leaning fir.

“Cut it down. You’ll have a better view of the rhodies,” one neighbor suggested.

But why? I loved seeing the fir’s textured bark arcing across the backyard and then shooting up to the sky.

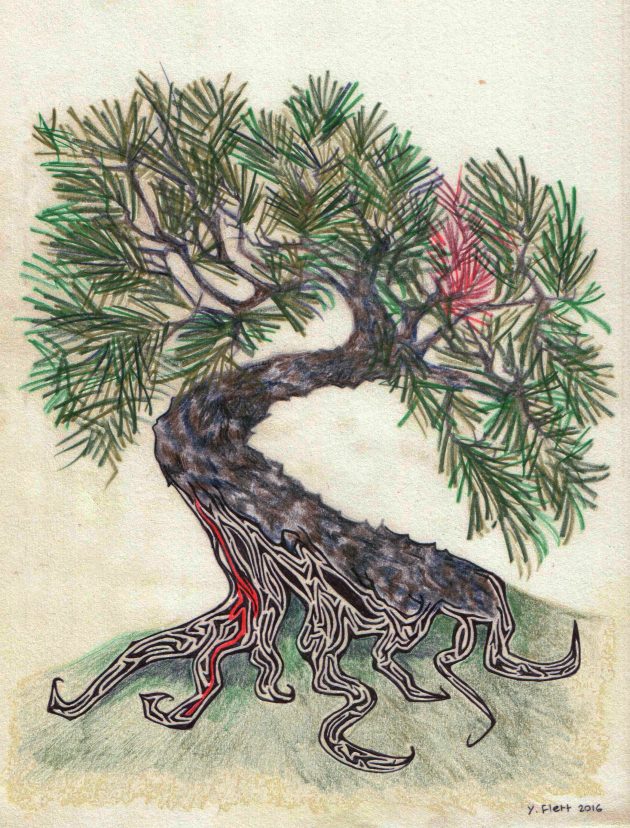

“This is the most beautiful tree I’ve ever seen, “ my mother said. “It’s a giant bonsai without wires.”

Mom appreciated the natural curve of the leaning fir. She carefully tended her miniature trees, tying a thin, almost invisible wire around a bonsai branch, lowering it slightly off balance toward the soil.

“This will bring out its imperfect beauty,” she said.

I’d stare at the potted bonsai, squinting so its wires disappeared, seeing its trunk arching toward the sun, its gnarled roots holding fast.

“Dig your roots deep and bend with the wind, too,” Mom used to say.

But one afternoon, while Dad was driving us into the yard after picking up fresh tofu we couldn’t get at the nearby Safeway, Mom suddenly lunged out of the moving car, the door swinging wide. That’s when I heard the blaring scream of a chainsaw.

We parked and rushed to Mom, seeing a man harnessed to our leaning fir. He was inching down the curved trunk, his chainsaw swinging at his side. Below him were branches, sawdust, and chunks of the butchered trunk scattered like bodies after a massacre.

“NO! Not this tree!” I cried out, running to the fir, its evergreen scent seeping into my nostrils and running down my throat like blood. Mom had hired a tree service to cut down a dead tree on the other side of the property, but the worker mistook our leaning fir for the dead one. Dad, his face anguished and red, clenched his fists; yet his unspoken anger rippled through our butchered tree, past its roots, down to his own severed youth—a frightened 17-year-old draft resister locked behind bars at McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary, a Japanese American kid who believed fighting for a country that forced his family and 120,000 other Japanese Americans behind barbed wire was wrong.

“Graft it,” Mom said in a quivery voice.

The tree man lifted his eyes sheepishly and nodded. From then on, each time the tree man visited, I followed behind him with hope, watching him climb the leaning tree and graft several one-foot limbs that looked like little hairs poking out of someone’s neck. But all the grafts eventually withered and fell to the ground, leaving only the beautiful curve of the decapitated trunk that would eventually die.

“’Shikata ga nai,’ There’s nothing we can do,” mother said, her body rigid as she picked up a shovel and turned toward the garden. I rarely saw my mom cry, but I sensed once her shovel hit the soil, she would.

She’d dig whenever she was frustrated, getting up in the dark with the birds and digging until daylight. It was as if she readied the earth and herself for the new day, coming into the kitchen with pink cheeks and hair flying. Grandma was this way, too, quietly shouldering an entire farm while raising children after her husband’s heart attack.

As cheerful as Mom was, I knew there were times she suffered without showing it to others. “I’d dig and dig until my tears stopped,” she said one time. Then I remembered those silent periods when she and Dad didn’t say much. That’s when I imagined her drenched with sweat, standing over a black hole, the sound of her sobs swallowed up in dirt.

Once I knew we couldn’t save the tree, I comforted myself by sitting near the leaning fir, noticing the moss that grew in patches along the roots and base of the trunk like a field of soft grass with tufts of white flowers in a miniature world.

I started carrying handfuls of dirt to the base of the trunk, opening my palms a crack, funneling the soil over the roots and moss creating a meandering path up a hill. Then I pulled the garden hose higher up the trunk, letting water trickle down the crevices of the bark like a stream running down a mountain. Day after day, I brought tiny flowers, clover, or teardrop leaves and pressed them into the dirt. At times, I noticed the small adornments had taken root. Other times I’d find lacy dew glittering on the moss, or a wisp of a feather left in a rose petal. That was when I began to believe fairies moved in.

And maybe they did. Although our leaning fir was decaying, it never fell over. Its roots were so strong that even after my college graduation, the curved trunk continued to arc across the yard and through the rhododendrons. At some point though, my mother said the trunk needed to be cut down or it might unexpectedly fall.

Mom might have made this decision after I married and started my own family. Or maybe it was sometime after Dad’s stroke, which left him hunched with one leg dragging. What I do know is our giant fir never really disappeared. Its roots hung on forever, transforming from a curved tree that leaned across our yard and arched to the sun, to a miniature world of fairies, and then to a soft mound of dirt nestled under the fragrance of jasmine, lavender and rhododendron blossoms the size of honeydew.

It was not until much later, after my children were grown and I had learned not to expect too much from life, that my own joints began to knot and ache, and I began to see all of life as a giant bonsai. That’s when each small moment became more imperfect and beautiful than I had ever imagined.

Sara Yamasaki is a writer, teacher, language-learning specialist, and founder of the Moving Words Writing Clinic. A graduate of the University of Washington with a master’s of arts degree in teaching writing, her poetry has been published in Calyx and Echoes From Gold Mountain, book reviews and articles in the International Examinerl. She is a 2015 Hedgebrook Writing Residency recipient, member of the Salish Sea Writer’s Collective, and resides in Seattle, Washington. www.movingwordsclinic.com