“What is war for?

Who and what are we defending from whom?”

— Ota Masahide, former Governor of Okinawa

President of Ota Peace Research Institute

[T]hings start off quite innocently. I receive two tickets from a colleague at school. On them is printed “Okinawa LIVE.” On the appointed day I arrive at the venue, Higashi Honganji, a large Buddhist temple in midtown Kyoto.

My husband, child, and I cross the vast pigeon-thronged gravel spaces of the temple precincts, reach the correct hall and are greeted warmly by monks. Their shaven heads are blue-tinted, and traditional white tabi socks peek out like rabbits’ paws beneath the hems of their black robes. The monks bow deeply in greeting, palms together and held high. The ever-present temple incense fills the air, and I inhale deeply, hoping it will somehow purify me. I am in a temple — the house of Buddha.

The auditorium is large, and filled. Hundreds upon hundreds of people have come to hear the Okinawan message. On center stage, a man stands alone, holding a sanshin, the traditional Okinawa three-stringed instrument. “We can only fight through our music, it is all we have,” he says. And an hour and a half passes by as the truth of Okinawa’s recent history spills out, accompanied by intermittent notes played on the sanshin — sounds of nodding agreement.

The speaker is Chibana Shoichi, an Okinawan. Labelled an “anti-base activist” by Time magazine [April/May 1997], perhaps he is more of a peace activist; one who out of love tries to protect the children, the people, the land, and the sea from being misused and ill-treated. Famous — or infamous — for burning the Japanese Hinomaru flag at a National Athletic meet held in his hometown of Yomitan in 1987, Chibana has spent much of his life trying to save Okinawa.

A fifteen-minute interval separates Chibana’s speech from the live music event, and I purchase many Okinawan goods: natural salt, lime juice, black sugar, and hand-woven textiles. I return to my seat hearing the crash of ocean waves; a background tape of the Okinawan seashore. A lapping of waves immediately slows me down, and in moments my mind and body are being lulled towards sleep. Then the magic begins.

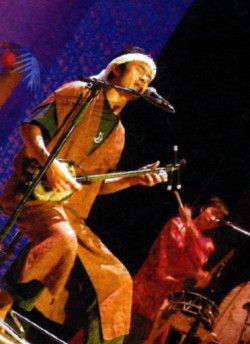

I’m not a cry-baby, yet torrents of salty water fall from my eyes, matting my long hair. Black lines stream down my face as mascara mixes with tears. It’s the music. Performed by a young Okinawan who’s not cool like our northern Edokko , but barefoot and wrapped in the traditional woven robe of his island, singing and playing from an innermost, almost forgotten depth of heart, with a plea for help. It’s so rare to hear such an artist. To hear him play, natural, drifting, in ebb and flow; to abandon thought and be with it — the sound. Heart is disturbed, one is awakened, the sound stirring inside.

I had almost forgotten this feeling, of music that moves the soul.

I had almost forgotten this feeling, of music that moves the soul.

Sounds played softly, then strongly, strong then soft, that disappear only to return, darkness, then light, and into darkness. Next, andante tempos, livelier pieces, followed by the traditional Okinawan lilt that catches me every time; a riff so unique, stirring, heart-wrenching, that spectators become participants, begin dancing. Children, women, old people, young men, alone, in pairs, jump onto the stage and into the aisles. My tears fall again as I realize the treasure of Okinawa in its music, in their spirit. So much joy, conjured up by one man and a three-stringed box covered in snake-skin.

The music connects us. As the hundreds of people dance and sing, swaying, waving their bodies and arms with joy, in a temple, in the afternoon, with no sake in sight, I awaken deeply to the message from Okinawa.

I am sitting with the lecturer, Chibana Shoichi. We are in Okinawa, and I want to help, if I can.

At Chibana’s house, five new rooms stand neatly side-by-side in the backyard. Four are rented out to guests, and one is set aside as a meeting room. Chibana’s writings lie open on a low table. Okinawa videos are stacked up against a wall. Magazine interviews with Chibana have the pages marked for easy finding. In the evenings, guests visit this room to talk with Chibana about Okinawa.

This morning, after an early breakfast, Chibana’s father placed a sanshin in my hands, and gave me a lesson. More than an hour passed as over and over again he showed me the fingering on the neck and as I plucked the strings, the haunting Okinawan riff resounded. Our communication was only through the sounds and our souls — no words spoken, nor needed.

Okinawa is striving towards grassroots revitalization, Chibana tells us, as all the guests squeeze into his van. This is not the usual tour of the sights. He takes us to a weaving workshop. The women rise as we enter and bring us traditionally-made black sugar lumps to eat as we look at their works. All their looms are hand- and foot-operated. The intricate pattern emerges as fingers fly. The room is silent but for the sound of wood hitting wood at regular intervals, like a metronome, as silk threads are pulled taut in the looms.

Next, a dyeing workshop. Red, yellow, blue; large vats of primary colors, all created from nature: akane ( Rubia argyi) roots, onion skins, and ai (indigo) leaves. Then on to a pottery site.

The pottery grounds, Chibana tells me, were formerly a bomb disposal yard. At once, my body tenses. I begin to step gingerly, looking at where I place my feet. The floor is simply earth though — dusty red clay. The potters are young, bandanas on their heads; their bare feet are clay red too. The walls, the pots, all the same red. Like a sepia print where everything is one tone.

I admire the clay roof tiles, their irregular shapes all made by hand. Chibana hands me two from an old stack, my omiyage. Okinawan music comes from a worn cassette player, once black, now covered with red clay fingerprints.

Promotion of tourism is essential to the revitalization of Okinawan culture. In 1970, Okinawa had 360,000 visitors. In 2002 the total was 4.5 million. They spent 380 billion yen [US$3.16 billion]. In 2001, due to elevated fear of the military bases, and concerns about the G7 Summit that was held in Naha the same year, 680 Japanese mainland schools cancelled their annual field trips to Okinawa. The overall slump in tourism that year cost Okinawa 40 billion yen in lost income.

“In hotel resort complexes,” Chibana explains, “money is spent, but the guests leave empty-hearted, without having touched the villagers’ lives. Such resorts don’t help Okinawa’s hand-made revitalization plan, which Okinawans promote not only to enrich their own lives, but to touch others.”

We drive through the Yomitan airport. Though no longer used, only a few sections have been returned to the village by the U.S. military. Abandoned cars lie in disarray. I visualize the U.S. planes taking off from here to attack Tokyo in wartime. Airmen running to them, engines roaring. At the edge of the runway now lies an enormous pile of sugarcane. Chibana abruptly halts the van, jumps out without a word, and breaks long stems of cane across his knee. He returns with a fistful of cane stick, hands one to each of us and for a moment, I’m once again the child in the back seat, given a stick of candy by her father.

On April 2, 1945, in Yomitan, Okinawa, 84 civilians, including 47 infants and young children, died in a “group suicide” at Chibichirigama Cave.

When U.S. armed forces landed on the main island of Okinawa, 140 local people — 31 families — evacuated to the cave. They believed they would be killed if they were captured. When U.S. soldiers approached the cave, two older men set futons and clothes on fire.

Four mothers who had small babies extinguished the fire, saying, “If you want to die that much, go ahead and kill yourselves alone. We came here to try and survive. Why are you in such a hurry to die?” The older men retorted, “You traitors! If we are Japanese, we should die shouting ‘Long live the Emperor!’” But when two adults were shot by the soldiers outside the cave, the group believed that death was soon to come.

An 18-year-old girl asked her mother to kill her rather than be captured and killed by the enemy. The mother cut her daughter’s throat with a knife. Then she sat astride her son and stabbed him. A former military nurse grouped families together and gave them fatal shots of poison. A boy clubbed his mother to death. (He lived, and later became a priest). Futons were set alight and people waited for death. The soldiers entered the cave. Only 56 of the 140 people are said to have survived.

A large signboard stands in front of the cave entrance, prohibiting entry. Chibana leads us in as though the sign does not exist. Inside it is dark. A board stands against one wall of the cave. As I walk towards it, Chibana cautions me.

“Don’t touch that. There are still bones behind it.”

I say a silent prayer, bow, and leave the gravesite.

In total, 150,000 Okinawans died during the final battles of the Second World War, a third of the civilian population. The number exceeded the total of American and Japanese military casualties (over 23,000 and 91,000 respectively).

I’ve been at Chibana’s house for a few days now. His wife Yoko, warm, with a big easy Okinawan smile, dimples, blue-black hair held together in an Okinawan-style knot, invites me to do some of my laundry. At the end of the spin cycle, I gather wet T-shirts and bathing trunks, and climb up to an elevated platform to hang them for drying. As I climb, my eyes meet each step, then are level with the platform, and then rise to meet the sky as it appears — but directly in front of me, huge as though seen through a telephoto lens, looms the “elephant cage.” It is so close, I feel I can almost touch it. I have seen many photographs of this cage, yet it seems so big, taking up the entire sky — it’s not an elephant cage, but a sky cage. I let go of the laundry, and it plunges to the ground.

Two hundred meters in diameter and 37 meters in height, the cage is formally designated the Sobe Communications Site. This giant steel ring surrounds a device used to eavesdrop on communications traffic, for U.S. Navy intelligence-gathering purposes. The antenna can pick up all kinds of radio waves, from low frequency submarine communication to very high frequency radar. Military information from the Russia, North Korea and other countries is deciphered and analyzed by specialists and then sent immediately to the U.S.

Chibana tells me that legally it is no longer supposed to be used.

“Then why is it there?” I ask.

“Because they are using it illegally,” he answers.

The land that the cage stands on includes 236 square meters that used to be his great-grandfather’s land, and Chibana is fighting the Japanese government in court to have this ancestral soil returned to him.

Okinawa holds 75% of the US military facilities located in Japan (by area), on its 0.6% of Japan’s land mass. Close to 20% of Okinawa’s land area is occupied by US bases, while Chibana’s hometown of Yomitan is even now 45% occupied. In 1972, 53% of Okinawa’s population received base-related income. In 2002, only 5.3% of Okinawa’s income was derived from the bases. Currently, the Japanese government pays 60 billion yen annually as compensation to landowners. Meanwhile, the average Okinawan earns 2.3 million yen per year [about US$19,000] — only half the amount earned by his counterpart in Tokyo. Unemployment is 8.7% in Okinawa, compared with the mainland average of 5.4%.

My five-year-old child wants to swim. We follow road signs written in English and arrive at a monster resort building — I’ve never seen anything like it. We ask directions to the beach and arrive at a fenced-off area of sand; the fence recedes even into the ocean itself. Loudspeakers shouting mainland pop assail my ears. I long to hear the soothing sound of the waves. Neither coral nor shells lie on this beach: workers with rakes tirelessly comb the sand. Their job never seems to end; they are a part of the seascape, always in motion.

We escape for an uncharted beach simply by climbing over the ocean fence and into the waves. We don’t stop swimming until we are out of range of the noise, and can hear the sound of surf. Why are humans so fearful of nature, I muse.

Sand, full of coral, shells, tide pools; waves lapping on the shore. We are alone with the sea. My body, spirit, and soul begin to relax. I close my eyes and feel the peace.

Restored, the mind is emptied. Sound of a bird, cawing in the sky. Sound of a crawling insect crossing the sand. Sounds, usually so remote from our senses, turn full volume in silence. A softness, a sensitivity penetrates. And the ever-present sense of time, of a finite number of sand grains falling through the hourglass of life. Time becomes no time — unimportant in this realm of quietude. Then, an enormous beating of iron wings. I open my eyes to two U.S. military choppers, circling the sky, like hawks watching.

“This is Okinawa,” Chibana laments. “But freed by Japan from being a U.S. stronghold, Okinawa could become a sanctuary, as in the past. Not an American-style resort, offering luxurious escapism, but returning to our Okinawan roots, the naturalness that grounds us to the earth, the music that frees our hearts.”

“The people’s silence must be given voice — we must express ourselves,” he declares. “If Okinawa is able to instill changes, Japan as a whole will change too — assert herself more, and stand up against the control and pressure of the U.S.”

Chibana is continuing his personal campaign, touring mainland Japan and lecturing in universities, high schools and temples to raise awareness of Okinawa’s present situation.

Later the same day, I go into a store. It is a kind of obasan shop, from a time before convenience stores. It is so dark inside, I think it may be closed. Inside, stacked neatly to the ceiling, are ancient goods: needles, threads, packaged sweets. The small bananas and oranges look old too, even though fresh. The old proprietor sits so still, she may be asleep. No muzak is heard, but a little bird chirps loudly. I look around, searching out the sound — up and down, round and round. Sandwiched between a stack of crates and the ceiling I find it: an Okinawan bird, as tall as my finger, hopping up and down in a cage no larger than a loaf of bread. I leave the shop with some bananas, but still see the bird in my mind — hopping, hopping, crying, and mirroring my image of Okinawa and the Okinawans.

At a noodle shop, at the bottom of the Japanese/English menu: “You can pay in American dollars. One dollar = 100 yen.”

I see A&W, the hamburger and root beer chain from my childhood. In the supermarkets, goods I can usually only get from mail-order catalogues, like Nestles Quik and Listerine, are lined up along the shelves, next to the usual kanji-labeled mystery packages.

I feel as if I am in an American theme park, but with no entrance and no exit. Extending all along the main drag, behind a barbed wire fence, is the base — a long and lethal alligator flat on its belly, stretching into infinity. Although the side of the street facing the base is quasi-Okinawan, the military presence simply scares me. I long for the blue of the sea…

Dusk descends. I am at the shore. Sea and sky come together, touch in lacquered darkness. I can see the sky, and feel the sand. At times, the pureness of nature reveals itself to us as a deep love; an embracing of all humanity in which all is one.

In the dead of night. I return to my room. All are asleep, yet I can hear the sanshin and the Okinawan melody that will forever haunt me with its beauty. All are asleep but the grandfather. Playing the music of his people, for us, for himself, I don’t know.

Half a year passes before I see the young sanshin player again at Higashi Honganji, in Kyoto. Once more, sitting with strangers yet among friends, the music overwhelms me.

Afterwards, in a small room off-stage, we bow and exchange greetings. He is seated on the floor; the sanshin lying next to him looks small, almost like a child’s toy. I kneel, facing him, basking in a feeling of rare intimacy. His name is Yamashita Masao, and he is known as “Ma-chan,” which is also the name of his band. “Ma” is the first syllable of his given name, and “ -chan” an endearing suffix commonly added to Japanese children’s names. Ma-chan is from the island of Iriomote, far south of the main islands of Okinawa — a place known for nature, sun and sea.

Largely self-taught, he learned to play the sanshin from village elders at the many local festivals. “The sanshin is everywhere in Okinawa,” he says, shrugging off my compliments. “Now there are about 30 or 40 professional players in Okinawa. Our hope is that through our music we can show the heart of Okinawa, and encourage others to visit, to see the beauty of its nature and its soul.”

In ancient times Okinawa was independent, and known as Ryukyu Onkaku, the Ryukyu Kingdom. Before being annexed by Japan in 1865 this peaceful kingdom had no army. Looking into Ma-chan’s youthful face, I recall Chibana telling me how young Okinawans are picking up the traditional instruments, shamisen , jamisen, and sanshin, and proudly carrying on their culture. Okinawa has remained connected with its ancestral soul through its music, and this is how it has responded to an unimaginable military onslaught — with songs that are the spiritual poetry of peace, prayers for nature and for people.

We bow again, he departs; I am left holding the hope of Okinawa — the ancient teaching of the sanshin, the music and song of Okinawa; its gift to the people of Honshu, and the world.

I have a friend in Kyoto, a former soldier whose mind remains disturbed by his intensive military training. He knows he’s crazy, and travels the world sporadically, soul- searching for the truth. I tell him what I have learned about Okinawa, and ask for his response. He says:

This — as all things —

does not exist to be changed,

but for us to change.

His words send a shiver through me.

“I didn’t say it — it came from up there,” he says, pointing to the sky.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013