THE SUMO WRESTLERS stood on the woven-straw floor, looking like grounded parade balloons as they fidgeted on their feet in baggy sweat clothes. They had bandages on their arms and ankles, bruises and welts on their faces, bulbous ears scarred into sickly nuggets. They towered over me at six and seven feet, some pushing 400 pounds. At five-and-a-half feet and 135 pounds, I was the oddball.

In the corner of the room Nakahara, a giant who resembled Baby Huey, lay on his stomach playing video games on a small flat-screen television. Moriyasu, a wrestler with lean, muscular arms and a relatively square jaw, chattered sweetly on a cell phone under his blankets; when the talking stopped, his cell phone bleeped as he sent text messages. But soon all activity ceased, as the enormous but exhausted wrestlers breathed heavily around me.

This wasn’t my first personal encounter with sumo wrestlers. When I first came to Japan — to work as a teacher and study Japanese — I lived in a quiet part of Tokyo down the street from a sumo stable. I ran into wrestlers nearly every day, shopping at the 7-Eleven or washing clothes at the laundromat. Since I worked and socialized in a modern, polished, international Japan, I liked living near someplace connected to the country’s distant past. The wrestlers represented a part of Japan that had lasted unchanged, perhaps for millennia.

Or so I thought. Years later, back in America, I did some reading and learned that sumo wasn’t as ancient as it seems: What we know as sumo today was only created in the late 18th-century when promoters reinvented prize-fighting to make it palatable to Japan’s martial government. I wondered what life was like inside the stables, where actual people spend years of their lives sustaining the fiction of sumo by living according to its severe rules.

So now I was back in Tokyo, where the master of Hanaregoma Sumo Stable in the city’s northwest was going to let me spend a few of the weeks before the upcoming January tournament pretending to be a rookie wrestler.

I was ready for a beating.

[T]he wrestlers had already started stirring from their naps when a young grappler slid open the bedroom door and entered with a broom and a stack of garbage bags. He started sweeping as the wrestlers in the room folded their futons out of his way. The stable’s highest-ranking wrestlers, with whom I shared the room, could sleep later and didn’t have to straighten up after themselves.

I rolled up my bedding and went downstairs, where the low-ranking wrestlers had long been awake, mopping the hallway, scrubbing the bathrooms and sweeping the common room’s straw floor. One side of the floor ended with a three-foot drop to the adjacent earthen-floored room where the wrestlers train. Narrow straw sacks were half buried end-to-end lengthwise, forming a circle in the middle of the floor.

In the kitchen, which smelled like rice wine and soy sauce, enormous steaming pots sat on the burners and three of the wrestlers were cutting giant hunks of meat. I asked if I could help, but the wresters waved me off and told me to sit down at one of the three low tables now arranged on the common room floor.

The dinner of chanko nabe — the hearty, protein-rich staple of the sumo diet — left over from the afternoon was served around six in the evening. It consisted of bits of bony fish floating in a sour, murky miso base. We also ate salty little cured fish, slabs of cold fatty pork, and boiled potatoes in an oily ground-beef sauce. I picked at the food, wondering how I’d stomach this diet. But the wrestlers ate heartily: Getting fat is nearly as important to their training regimen as their morning wrestling drills, and they spend most of their afternoons and evenings either eating or sleeping.

After dinner, the junior wrestlers started taking plates, bowls and serving dishes into the kitchen to be washed. Hiroki, a low-ranked wrestler whose younger brother was also at the stable, approached me. “There’s one more person for you to meet,” he said. “He’s a sekitori.”

Sekitori wrestle in sumo’s upper division. The stable’s lone sekitori, Ishide, lived upstairs in a private room that his high rank had earned him. On our way up to the room, Hiroki kept telling me, “Just say, ‘My name is Jacob, yoroshiku onegaishimasu’,” standard words of greeting that he didn’t want me to flub.

Upstairs, a few wrestlers milled around Ishide’s doorway. I walked in and saw him sitting cross-legged on the straw floor of his room in a loosely sashed white robe. He had a light complexion and squinty eyes, and his hair was falling out of his topknot. A futon was rolled up behind him and he sat in front of a television that was perched atop a DVD player, stereo components, and a video game console whose control pad rested at his knees.

“My name is Jacob, yoroshiku onegaishimasu,” I said.

He asked me how old I was and I told him I was 30.

“That’s old,” he said. I learned later that he was 27, and had joined the stable when he was 15.

Then he asked, “Are you really going to fight?”

“Yes,” I answered tentatively. He looked at me askance, then nodded dismissively. The wrestlers hustled me out of the room.

“You did good,” Hiroki told me on our way downstairs. In the common room, the wrestlers had started pulling their futons from the closet for the night, so I went upstairs to my own bed.

Each of the five wrestlers in the upstairs room had a section of floor where he slept surrounded by his possessions. Everyone had a little television and a shelf with toiletries, comic books and compact discs. There was a statue of a hand with an extended middle finger on the windowsill, pictures of swimsuit models on the wall, and booze bottles displayed like trophies on bookshelves.

These meager possessions were extravagant compared to those of the eight low-ranking guys who slept in the common room on futons they stored in the closet during the day. With no permanent space of their own, most just had a cell phone and a Gameboy, though they all dipped into the stream of communal comic books and magazines that flowed through the stable.

The wrestlers upstairs were generally older than the ones downstairs, but that’s not what earned them their superior rank. The sumo world operates as a brutish meritocracy: wrestlers rise and fall based on the number of matches they win in the six tournaments held in Japan each year. A wrestler can remain at the bottom indefinitely if he has a bad tournament record.

One quiet, serious, 23-year-old wrestler named Mitsui had been with the stable for six years, but was still one of its lowest-ranked fighters and still slept downstairs. He had a cheap DVD player he attached to an old, boxy portable television so he could choose his own movies — and when to watch them — instead of relying on whatever the group played on the communal TV. His setup was small enough for him to stash in the closet during the day. But when I saw Mitsui at night with power cords slinking under his covers, and a towel draped over his television and his head like a tent so he wouldn’t bother the other wrestlers on the floor inches away, I couldn’t help but think about Ishide upstairs. He was probably sitting that very moment in his private room in front of a big flat-screen.

[W]hen I woke to my first morning at the stable, Saita, the hulk whose futon was across from my own, was sitting on the floor in the dark, bandaging his wrists and ankles.

In the hallway downstairs I ran into Batto, a Mongolian and the stable’s only non-Japanese wrestler. He was wearing a coarse canvas mawashi — the diaper-like sumo loincloth — and he motioned for me to enter the now empty common room. Midway down the ledge overlooking the practice floor sat an empty cushion with a clean ashtray on one side and a fresh sports newspaper on the other. They awaited the stable’s master, who lived with his wife in a separate apartment within the building.

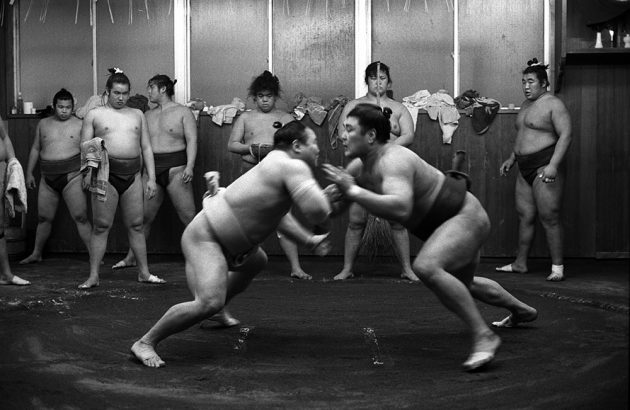

The wrestlers stood in rows on the earthen floor, taking turns counting to ten: with each count, all the wrestlers slapped a thigh, lifted a leg sideways, stamped it down, and squatted. The leg lifts didn’t occur in unison, but in a lazy syncopation.

They all wore matching gray mawashi, and about half had their feet or hands or shoulders bandaged. They were all big, of course, but not uniformly so. Some had solid, healthy guts, protruding but toned. Others had giant droopy breasts and folds of fat pouring out the legs of their mawashi. But when they stamped down and their loose flesh pressed against their bodies, rippling muscle showed through even the flabbiest of physiques.

Following their leg stretches, pairs of wrestlers began taking turns facing off across the center of the ring and charging each other. Sometimes heads collided and I could hear skulls knock together like billiard balls. Other times they slammed into each other belly to belly sounding like a sandbag tossed against a levee. They grunted as they shoved each other around the ring, their callused feet scraping the dirt floor. Most matches ended after mere seconds of scuffling, when one of the wrestlers beat his opponent by maneuvering him out of the ring or throwing him to the floor, sometimes with an impact that shook the room.

The lowest-ranked wrestlers, who generally won through brute force, finished their matches about an hour into practice. They left to fill the stable’s communal bathtub, help prepare lunch and run other errands, ceding the ring to their seniors: savvier fighters who relied less on sheer strength than skillful maneuvering.

Soon Ishide strode onto the dirt floor in a white mawashi. The other wrestlers nodded deferentially in his direction as he walked to the faucet in the opposite corner of the room. He gargled and spit out mouthfuls of water in an act of ritual purification that none of the other wrestlers had performed.

Although Ishide was the most accomplished wrestler in the room, he was hardly the biggest. His arms and legs were lean and knotted with muscle, and his stomach was round and solid, like a polished stone. He remained in the corner of the practice floor, doing squats and leg lifts.

Finally, about two hours into practice, the stablemaster came down from his apartment. He was a serious-faced man who had slimmed down since his own wrestling days. He sat on the cushion that awaited him and smoked cigarettes while he watched the matches, sometimes shouting instructions into the ring or berating the losers.

In the morning’s last set of matches, the stable’s top-ranking fighters took turns wrestling Ishide, but few could beat him. He lost one match to the mountain-sized Nakahara, who trapped him in a bear hug on the edge of the ring and used his massive stomach as a lever to pick him up off his feet and deposit him out of bounds.

But Ishide could usually beat the much taller and fatter Nakahara. “What are you going to do?” I heard him trash talking into Nakahara’s ear during one match as he danced the giant around the ring before stepping to the side and letting him collapse on his own.

I was starting to worry: I was here to sample sumo life, which revolves around these morning practice sessions. But I couldn’t train with these guys. I’d be crushed. When practice ended, though, the stablemaster leaned toward me and asked, “So, you want to give it a try?”

“I would like to,” I said, trying to back out gracefully. “But it looks so difficult. I really wouldn’t know what I’m doing.”

“Of course not, but someone can teach you a little at a time,” he said. “And if you get scared, you can back out whenever you want.” My fears diminished; I was back in the game. I would join the next training session.

As the other wrestlers relaxed, Batto—the Mongolian—aired out Ishide’s ceremonial aprons on a clothesline he’d strung across the practice area. Batto was one of the junior wrestlers whom the stablemaster had assigned to be Ishide’s attendants, which his rank afforded him. The Mongolian had only been at the stable for a year and a half, but, like many foreign wrestlers, he was rapidly ascending its ranks.

That night, I joined the wrestlers in front of the common room television. Suddenly, Ishide entered with a yellow towel around his waist. Batto followed with his boxer shorts bunched up over his thighs so their flapping hems would stay dry while he bathed Ishide, another job he performed as an attendant.

The wrestlers around me jumped to their feet in deference to Ishide, who stopped in front of the heater and changed into a pair of boxers. Then he sat down beside Mitsui, the wrestler with his own DVD player. Moments later, Ishide asked me how much of the Japanese television dialogue I understood.

“About 60 percent,” I answered.

He punched Mitsui. “I told you he doesn’t understand everything,” he said. Then he pointed to Mitsui and said to me, “Mitsui only understands 40 percent,” and everyone in the room laughed. Next he pointed to another wrestler who’d gotten up to dry Ishide’s towel in front of the heater. “He only understands 15 percent,” he said, and the laughter grew louder.

When the laughing stopped, Ishide stood and put a wrestler seated on the floor reading a comic book in a headlock. The wrestler started coughing and gagging and his face turned red. Ishide released him, but the wrestler wheezed on.

Ishide ruled the roost through taunts and bullying. But he probably wasn’t such a bad guy once you got to know him. He likely spent most of his time holed up alone in his room because he was tired of being obnoxious. Being responsible for the torture and humiliation of a sprawling house of overweight jocks is hard work. But it’s part of his job description and the prerogative of his rank. He sits atop a rigid social structure where status—earned through success in the ring—determines the very quality of one’s life.

It’s odd that such a stiff hierarchy exists in sumo, even as it eases in the rest of Japan. Sumo emerged from an explicitly status-resistant milieu, the demimonde of 17th and 18th century Japan’s pleasure quarters, which existed alongside its mirror image, the official Japan of its martial rulers, the shogun.

Another distinguishing feature of the shogun’s Japan, aside from the intense stratification, was the shogun’s insistence that Japan’s feudal nobility — the samurai — spend every second year in the capital city of Edo, now Tokyo, to keep them from becoming too powerful in their home provinces. By the mid-18th century, these samurai and the increasingly affluent merchants who provided for them had made Edo the world’s most populous city with over one million residents.

A massive entertainment district sprang up to serve these bored samurai and nouveau riche urbanites on the edge of the city, where the shogun calculated it would least harm the established social order. In these glittery, rough-and-tumble pleasure quarters, official status mattered much less than the amount of money you had and how much panache you exhibited in its brothels and watering holes.

Street-corner sumo matches, whose combatants included disenfranchised samurai and migrants from the countryside, were among the district’s most popular entertainments. They were rough, raw, brutal competitions, sometimes fought to the death. But toward the end of the 18th century, these prizefights faced a zealous shogun’s crackdown on the entertainment district. That’s when a contingent of fight promoters, led by the scion of an established family who claimed to have inherited secrets of sumo linking it to 12th-century court wrestling, petitioned the shogun to allow the matches. The shogun relented, and sumo matches were soon even held in his castle. Sumo, now dressed in the vestments of Japan’s semi-official religion, Shinto, had been taken out of the entertainment quarters, adopted by the court, and established as part of official culture. There it absorbed the stratification of the shogun’s Japan that fossilized into the strict hierarchy that exists in sumo today.

In the stable, I saw this hierarchy demonstrated in the servitude that junior wrestlers owed their superiors. It was one of the features of sumo life—along with their topknots, kimono and old-fashioned Japanese ring names — that made it an exaggerated form of Japanese-ness rooted in the myths and mores of a previous age. You can see whom this appeals to by looking at the audience at a sumo tournament: it’s made up of older Japanese who romanticize the country’s past because they’re alienated by the present and foreigners who see it as more authentic than modern Japanese life.

[E]arly mornings at the stable are a strange and silent time. The wrestlers don’t speak, though they mumble to themselves and breathe heavily as they drift through the halls in their light robes and silently bandage previous days’ wounds. I’m reluctant to interrupt this sober mood, but can’t prepare for the ring on my own. Finally, Hiroki sees me looking lost in the hallway by the bathing room and offers to help.

He pulls a rolled-up mawashi loincloth from the pile atop the nearby shelf and tells me to get undressed, which I do. To put on the mawashi, I have to straddle it, holding one end under my chin and forming the section between my legs into a sort of athletic cup. Then I spin around as Hiroki winds the remaining length of canvas around my waist like a belt. The mawashi orbits the waists of most of the wrestlers just a few times before it expends itself. But I have to keep twirling until the mawashi has almost layered itself into a coarse canvas tutu.

In the mawashi, I follow Hiroki onto the earthen practice floor, which is chilly to my bare feet. Murayoshi, the wrestler who brought me upstairs to my room when I arrived at the stable, enters the room after us and has me join the line of wrestlers doing their leg-lift exercise.

It’s harder than it looks. I have to keep my hands on my knees with my thumbs facing forward and elbows back during the squat; I have to keep my feet under my shoulders; my kicks have to go straight out with unbent knees. And before each kick, I have to slap myself noisily on the thigh. We do some 150 of these: a solid leg workout. I look around and see that even the heaviest wrestlers are sweating less than I.

Then, following the other wrestlers, I sit my nearly bare backside on the dirt floor and spread my legs as wide as they’ll go. We touch our toes, which the layers of heavy mawashi digging into my stomach make especially tough. The wrestlers lean forward, bringing their stomachs close to the ground, which I can’t do. Murayoshi pushes my legs farther apart with the ball of his foot and gently presses on my back, bringing my chest closer to the ground. Something in my inner left thigh snaps and I feel a dull pain.

When the training bouts start, Murayoshi tells me to keep doing leg lifts. The motion keeps me warm, despite the fact that I’m nearly naked on a dirt floor in an unheated room long before dawn in late December. But once the other wrestlers stop, I do too. I feel silly doing it by myself.

Soon, though, the stable’s assistant coach arrives and motions for me to start again. I do leg lifts and don’t stop for an hour or more, afraid that he’ll see me standing still. He chastised me for showing disrespect by not sitting with my legs crossed when I was watching practice in the common room the other day, and I don’t want to get in trouble with him again. I do the leg lifts until my hips ache and I can barely support myself on one leg while kicking out with the other.

When the practice matches end, Ishide asks me if I’m ready to fight. I hold out my arms and wave toward myself as if to say, “Bring it on,” hoping he gets the joke. Ishide waves me into the ring and the wrestlers chuckle, some with disbelief, others with discomfort. He pulls Hiroki, who towers over me and weighs double what I do, into the ring. Hiroki plants his feet on the ground and extends his arms outward in preparation for butsukari practice, where one wrestler tries to push another across the ring like a human zamboni in order to build hip and thigh strength. As instructed, I start from a squat at the edge of the ring with my fists on the ground before me and throw myself at him, meeting his chest with my open palms.

He doesn’t budge.

Ishide corrects my technique — he tells me to collide into Hiroki’s chest with my head —— and Hiroki points to the reddened spot below his right shoulder where the impact should occur. I charge again — it’s like ramming my head into a punching bag, and I feel my neck sprain. But this time he slides an inch or two.

Ishide tells me I’m still doing it wrong: I should approach him without lifting my feet off the ground. So for my final charge, I shuffle toward Hiroki, sliding my feet along the ground as the friction warms their soles, and I meet his chest with my palms and head. He shifts another inch or so.

Next we wrestle for real. We collide into each other from opposite sides of the ring; Hiroki graciously absorbs my impact instead of charging into me like he would an actual opponent. My arms scramble, trying to get him into a hold. Ishide calls out, “Grab his mawashi.”

Yanking each other’s mawashi, we somehow get near the edge of the ring with Hiroki close to its sunken-straw boundary. Ishide shouts at me: “Push!” But it’s no use: I can’t move Hiroki. Instead, he pushes me clear across the ring, where I keep myself within its bounds by seizing a toehold under the sunken-straw bales. Before he can lift me up and toss me out, Ishide ends the match.

A few of the wrestlers crowd around me. “How was it?” asks Murayoshi, smiling slyly as he pulls me into the circle of wrestlers that formed around the edge of the ring, where we do a few hundred squats that I can barely manage after the hours of leg lifts. When the session ends, someone brings me a robe. “Aren’t you cold?” Ishide asks me. “Have a seat in front of the heater.”

I’m not being treated like a normal new recruit. But maybe, I think, after a few more times in the ring, they’ll go harder on me.

[W]hen I woke the next morning and tried to stand, I nearly collapsed. I’d clearly done too many leg lifts. From my knees to my pelvis, from my calves to my buttocks, inner thigh, outer thigh, everywhere, all I felt was pain. It hurt to walk. It hurt to stand. It hurt to sit.

I considered skipping practice, since I probably wouldn’t make it through even one round of leg lifts. But I didn’t want the guys to think I was a weakling or the stablemaster to think I was insincere about wanting to sample authentic sumo life. So I decided to do some test leg lifts. At the foot of my futon, I squatted, kicked up my right leg, squatted again, then kicked up my left. Each movement was awkward and painful.

“What are you doing?” asked Murayoshi, who woke in his futon and saw me doing leg lifts alone in the dark.

“My legs hurt,” I answered.

“Then don’t even bother putting on a mawashi,” he said, which — frankly — is what I wanted to hear.

I watched practice that morning from the common room floor. When it ended the wrestlers reached into a closet and took out shovels, trowels and rakes and started digging into the dirt floor. This began the ring-rebuilding process that the stable completes thrice yearly. It would take three days: enough time, I thought, for my legs to recover.

Tatsuya pointed to the second-highest row. “Ishide,” he said, pointing to the stable’s star wrestler’s name. It was printed in characters barely one-fourth the size of those of the wrestlers on the row above. Then Tatsuya showed me his own name on the lowest level printed in characters so fine that he had to squint and search for it among all the others.

“I want to get up here,” said Tatsuya, pointing to the top row, where the name of the grand champion — a Mongolian — was printed in the largest type of all. Tatsuya had joined the stable nearly two years earlier, a couple months before Batto, the stable’s own Mongolian. But unlike Batto, he hadn’t gotten far beyond the sport’s lowest rank.

Tatsuya had followed Hiroki into the stable. Many of the wrestlers at the stable were teenagers from Japan’s countryside and depressed industrial towns, and brothers Tatsuya and Hiroki — from a run-down city near Osaka — were no exception. They were built big and they didn’t like school. Without any clear job prospects at home, coming to Tokyo to do sumo lent their lives some direction and gave them an excuse to skip high school.

It wasn’t hard for the brothers to enter professional sumo. Sumo once offered poor, uneducated teenaged boys a rare escape from their impoverished lives, much like professional sports can be a way out of America’s ghettos. Enough people wanted to get into the sport for stables to accept only those who showed great potential. But these days, with so many other choices available, few Japanese want to eschew modern Japan and live a strenuous, servile existence in a stable, with only the slightest chance of ever gaining any fame as a wrestler. Virtually any teenage boy in Japan who meets the sumo association’s height and weight requirements is guaranteed a place in a stable if he wants it—whether or not he has any aptitude for the sport.

This is one reason why foreign wrestlers do so much better than their Japanese counterparts: it’s harder for them to enter the sport. Each stable is generally allowed just one foreigner, so they make sure he’s talented.

[B]y the time the ring had been fully rebuilt, about a week into my stay at the stable, my legs had stopped hurting and I was determined to wrestle again. But a new phase of stable life had begun: with the January tournament just weeks away, wrestlers from other stables were going to join practice. Since wrestlers don’t fight their stablemates in tournament matches, this would give them a chance to train against fighters they might meet in the ring. When I told the wrestlers I hoped to try fighting again, they told me I’d be in the way.

I decided to check with the stablemaster before joining in again. But he hadn’t been attending practice, and I didn’t want to disturb him in his apartment, so I spent the next few mornings watching practice in the common room, where I was sometimes joined by the stable’s neighborhood financial backers, all older Japanese men.

Yet, although the wrestlers didn’t want me to train with them, they seemed content to have me around. I even bathed with the wrestlers in the communal bath, a tile cistern no wider — though much deeper — than a standard American bathtub; its water level always plunged from my neck to my waist when the wrestlers climbed out.

At dinner and while watching television, the wrestlers asked me questions about America, quizzed me on my music tastes, questioned me about what Japanese foods I could stomach. They also used me as a foil to ridicule each other’s alleged sexual predilections. One wrestler might say to me about another in a conspicuously loud voice, “He likes young girls.” Another wrestler, I’d be told, liked American women. Another one supposedly preferred men.

The wrestlers invented these stories because as far as I could tell they had no real love lives, which contradicted the lothario image that sumo wrestlers traditionally cultivated. Woodblock prints from the 17th and 18th centuries portray famous wrestlers in the company of noted beauties from the pleasure quarters, and today’s celebrity wrestlers, despite their exaggerated physiques, are still esteemed enough to be able to date and marry actresses and pop stars. But most wrestlers at my stable had no such luck. Hiroki, who joined the stable when he was 16, told me he’d never had a girlfriend.

The stablemaster prohibited all but the highest-ranked wrestlers from dating, but even if relationships were permitted, few wrestlers had the time or money to sustain one. And they certainly couldn’t take a girl back to the stable.

Yet, many of the wrestlers did receive a fair amount of physical affection — from each other. I doubt there was any actual homosexual sex occurring in the stable: for one, there was no place for a couple to find privacy. But there was a lot of ass grabbing, thigh caressing, belly stroking, breast clutching and general snuggling. It wasn’t unusual for a pair of wrestlers to lie on the floor in the evening watching television in each other’s unselfconscious embrace. It was actually kind of cute to see these big, tough guys cuddling like girls at a slumber party.

[O]nce I secured the stablemaster’s approval to join practice again, I hopped back into the ring, disregarding whether the wrestlers wanted me there. But the atmosphere at practice had become palpably different.

The sessions had gotten longer and more brutal. At one point Hiroki lost a match that he was on the verge of winning. Murayoshi marched over to him shouting insults and slapped him on the cheek three times with his full open hand. Hiroki stood there, taking the whacks and apologizing for losing.

Nobody helped me stretch or made sure I was doing my leg lifts correctly. The most attention I got was when Ishide sent a Mongolian wrestler from one of the other stables hurtling out of the ring at me, pinning me briefly against the wall and covering me with the sweaty dirt that coated his body. Murayoshi pulled me aside sternly, like I was a child who’d been playing in the street, and stood me in a less vulnerable spot on the practice floor.

I never wrestled that morning. And after practice, there wasn’t room for me in the circle of wrestlers doing squats, so I squatted alone off to the side. All morning long, in fact, I did nothing but do leg lifts to stay warm and feel foolish for being there at all.

I wasn’t bitter though. When I left the stable in a few days, I’d be disappointed about having been treated like a guest. But I was a guest and in the sumo stable—like the rest of Japan — guests are lavished with attention and courtesy, but are rarely fully accepted. I understood why the wrestlers didn’t have time to indulge my sumo fantasy: too much was on the line for them.

The stable’s wrestlers took their mochi making very seriously, putting on their mawashi for the occasion and spending an entire morning swinging wooden mallets on the practice floor. It was another example of the wrestlers doing something traditionally Japanese with a greater intensity than anywhere else in the country.

This has long been a function of sumo wrestling. The leaders of Japan’s late 19th-century modernization drive prohibited Japanese citizens from wearing topknots, but sumo wrestlers, serving as a vessel for Japan’s traditional identity, were permitted to keep theirs. These days, the wrestlers can’t stray more than a few blocks from their stables dressed in anything other than a kimono, while other Japanese dress like their counterparts in New York or London. Sumo life is steeped in Shinto mysticism, although modern Japan has one of the world’s most secular societies. The wrestlers are bound by codes of conduct that predate Japan’s contact with the West, while other Japanese move toward Western egalitarianism. They boast great strength and persistence, traits to which Japan’s post-war successes are popularly attributed, while their countrymen grow comfortable in their affluence. All this makes the sumo world feel more “Japanese” than the Japan that exists outside the stable.

It’s as though sumo really has become the container for traditional Japanese values that its 18th-century boosters imagined it to be, though perhaps not as they intended, since it is increasingly foreign wrestlers who dominate this distillation of traditional Japanese-ness. This irony is not lost on many Japanese, who lament their countrymen’s relative failure at their national sport.

I once saw a thin, white-haired man waiting by the wrestler’s entrance of the sumo stadium in Tokyo’s Ryogoku district, hoping to glimpse one of the fighters. I asked him whom he wanted to see.

“Kaio,” he answered, naming the only Japanese wrestler at the time who stood a chance of seizing a spot at the pinnacle of the sport alongside the Mongolian champ. “It’s a Japanese sport. It’s sad that there’s no Japanese grand champion.”

Why isn’t there one? I asked.

“Foreigners know hunger,” he answered. “Japanese have lost that.”

When the match before his ends, the announcer calls out Ishide’s name.

“Ishide!” come voices from all over the auditorium when he climbs onto the ring. “You go Ishide!”

Unlike the swift early matches between low-ranking fighters, the upper division wrestlers take their time. I watch Ishide get in the ring and take a ladleful of water into his mouth, then spit it out. He grabs a handful of salt from a bucket in the corner and sprinkles it onto his feet and legs in another purification ritual borrowed from Shinto. Then he walks into the center of the ring and faces his opponent.

But they don’t fight yet.

They return to their respective corners to sprinkle more salt on themselves, and then do leg lifts for the crowd.

“Ishide!” yells someone behind me.

They return to the center of the ring, but again only stare into each other’s eyes before going back to their corners, where they towel themselves off and once more dip their hands into their salt buckets. Ishide’s opponent takes a huge handful and throws it arrogantly into the ring. The crowd roars.

Ishide’s handful is much smaller. He scatters it gently into the ring, then softly rubs it into the earthen floor with his foot. The crowd cheers even more loudly for this. Ishide keeps his head tilted down. He is temperate and humble.

“Go Ishide!” I hear again to my side.

Again they return to the center of the ring where they gaze fiercely into each other’s eyes. And this time — having sufficiently psyched one another out — they stay put. When the referee signals with his paddle, they tap the ground with their fists and lunge at each other.

Within moments, Ishide winds his arm behind his opponent’s back and flings him from the ring. The crowd cheers wildly, louder than I’ve heard all morning.

I cheer too.