Text and photos by Edward J. Taylor

Nothing reminds you that you’re in Shikoku like spotting a ubiquitous figure in white. I see my first pilgrim within seconds of stepping from the train, a young man making the rounds of the island’s world-famous pilgrimage. I too had worn similar garb when I followed iconic holy man Kobō Daishi around Shikoku on foot. But on this particular visit I am tracing the footsteps of another man, Sakamoto Ryōma.

Ryōma was born in 1836 to a family that held the lowest rank in the samurai hierarchy, a title purchased by an ancestor who had made his name as a sake brewer. Despite these humble beginnings, Ryōma went on to become a master swordsman, and in recognition of his skill, his Tosa clan allowed him to continue his training in Edo. It was during his time in the old capital that American Naval Commodore Matthew Perry sailed to Japan to forcibly end the shogunate’s policy of national isolationism. Ryōma and many of his samurai colleagues resisted this opening to the West, and began to agitate for the shogun’s overthrow. As the Tosa clan too was anti-shogun, Ryōma got involved with many local political groups upon his return home, yet disagreeing with the limited scale of their proposed reforms, he left the domain without permission in 1862, saying he was going out to see the cherry blossoms.

Now a masterless samurai, he attempted to assassinate Katsu Kaishū,, a high-ranking official in the shogunate who supported Westernization. But instead of killing him, Ryōma was swayed by Katsu to join the cause, and with this shift he saw the wisdom of negotiation over force. Ryōma’s renown grew as he took part in important negotiations and alliances, and more so when he established the first Japanese trading company. Despite (or due to) these achievements, Ryōma was still considered an outlaw by the authorities, who were never more than a few steps behind.

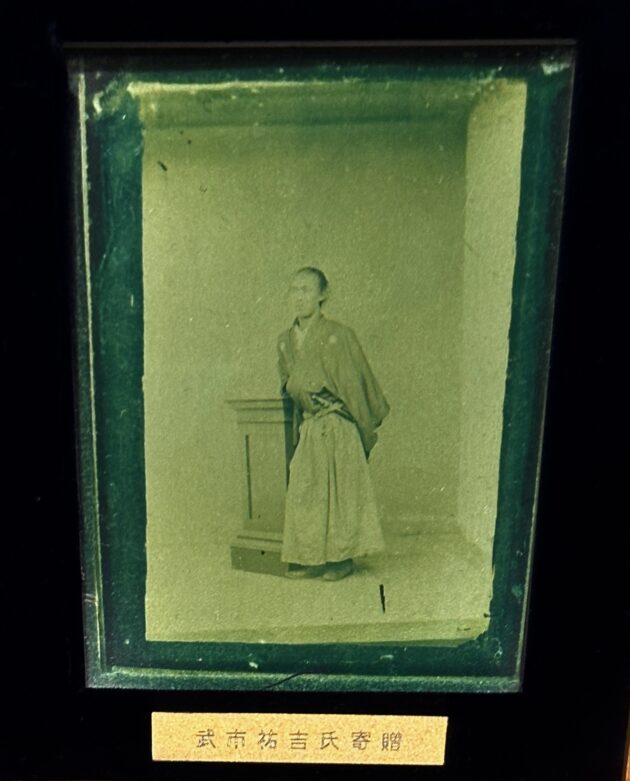

In front of Kōchi Station stands an imposing trio of tough-looking samurai, superimposed against the even taller Prefectural Police Station behind. It’s the perfect metaphor for Ryōma’s story, and thus an auspicious start to my own journey, which in practicality begins at Yamauchi Jinja, the tutelary shrine for the Yamauchi clan who were the feudal heads of Tosa. (In its grounds, I quickly catch sight of a statue of the clan’s final lord, Yodo, who called himself Gejikai-do or “drunken lord of the whales and seas,” his marble hands raising a cup in honor of the restoration of the Meiji Emperor.) Originally built within the grounds of Kōchi Castle, the shrine was moved here towards the end of the feudal period. Ryōma would have long left the clan by then, and in that spirit there is no trace of him here. Still, the grounds are pretty, set in a narrow stretch of green alongside the Kagami River. Behind the shrine is a long nagaya row-house that was once part of the Yamauchi clan residence. Despite its rickety appearance, it is one of the few remaining authentic samurai nagaya in the country and a national cultural property. I find Ryōma within, his photograph included as part of an exhibit on Tosa’s important figures, hanging above a number of intricately-carved miniatures of wooden ships.

Ryōma’s birthplace is a short walk away, small and unpretentious as befitting his low-ranking family status. Though the exhibit is not English friendly, I am immediately drawn to the old-timey Edo period vibe of wood and paper, with loads of cartoon illustrations that are no doubt popular with school groups. The museum also offers eight walking courses for Ryōma purists who want to dig deeper into the fine details of his youth and subsequent years as a samurai.

As a family of foot soldiers, the Sakamoto house was in close proximity to Kōchi-jo castle, a place it is safe to assume Ryōma would have visited in his time. Standing proudly and prominently at the city center, it has the distinction of being one of Japan’s twelve original remaining castles, and the best preserved. Originally built between 1601 and 1611, most of its current structures were rebuilt in 1748 after a fire. Despite it being a crisp and perfect autumn Saturday, the grounds are free of crowds, though as I wend my way up to the castle keep I am greeted by numerous statues of prominent figures intertwined with the castle’s history. I am coming to find that Kochi city loves statues.

Due to an optical illusion, the keep proves to be a lot smaller than it appears from below. Yet once inside, as it feels big again. All castles in Japan function as museums, and this one is particularly good, the centerpiece being the large-scale model of how the grounds and the surrounding jōka-machi town looked in their heyday. But the highlight for me is the upper level of the keep. Unique in being utilized as a both a residence and for military purposes, the warlords would have delighted in the views of their town stretching toward mountain and sea, neatly cut by the angled roof lines that fan out below. Many of Japan’s remaining castles can be found in Shikoku, their host cities having gone to great lengths to cultivate picturesque parks to surround them. The greenery and the tiled feudal structures blend well with the surrounding city, as if the modern buildings beyond are some sort of extension. Despite major renovation in the 1950s, it is refreshing how original everything looks, not overly restored as is the case of too many historical sites the world over.

On my return to the park below, the literary museum tempts, but it is overruled by the needs of the stomach. Hirome Market is a mere block away. I first visited during my 2009 pilgrimage, and my palate has ever-remembered Kochi’s renowned Katsuo Tataki, seared bonito. Upon approach, you feel as if you are going to pass through one of those long, narrow shopping arcades so common to Japan, but once inside you find yourself in a warren of right angles, filled with food stands. The picnic table seating at center is near full, probably occupied by groups on a bus tour. My memories of dinners here were quieter and recalled more locals. I find an empty seat and try seared bonito from two neighboring shops, promising to try a couple more in the quiet of evening.

Good meals should always be followed by a good walk, and in that spirit, I make my way to the botanical gardens, leaving Ryōma on his own for a while. The Kochi Prefectural Makino Botanical Garden was built in 1958 to honor the life and work of Kochi native Makino Tomitaro , known as the “Father of Japanese Botany” for his pioneering work in the field. The garden’s eight hectares contain 3000 species of plants, and are unique in being tidily stretched along the ridge top of Mount Godai, rather than being laid out on flat ground as is more common. A person could spend a half day getting lost here, following all the little serpentine paths that branch off the main route. The spectacular views from the North Garden take in rice fields extending to the hills further inland, the garden slopes coming ablaze in color during cherry blossom season. But if time is short, its best to focus on the South Garden. Once part of the adjacent Chikurin-ji Temple, its terraced levels lead down to a series of small ponds and rock gardens. I am amazed by the size of the tropical water lilies inside the greenhouse, and enjoy following the paths spiraling around in a way reminiscent of caves in the sci-fi films of my youth.

Neighboring Chikurin-ji reveals its age in the form of copious statuary lining the main path, blending near-invisibly into the well-tended moss. The temple is relatively free of people today, so I sit awhile before the five-tiered pagoda, enjoying the quiet. The temple’s roots date to 724, founded by wandering holy man Gyogi, before becoming part of the Shikoku pilgrimage. These days, the maples above are the temple’s biggest draw, and though not yet in color, I find consolation in the 14th century garden, built by legendary designer Muso Kokushi along Tang Dynasty lines, in a way that draws comparisons with Mount Wutai, one of China’s most sacred peaks. The garden was named a Japanese National Place of Scenic Beauty in 2004. On the way out, I spot the rough and irregular set of stone steps that my knees remember all too well from my pilgrimage 15 years before. Luckily, today I’m only going as far as the bus stop in the car park.

I rejoin Ryōma at the Sakamoto Ryōma Memorial Museum, built atop the low mount that marked the site of Urado Castle, Kōchi-jo’s predecessor. Built in 1991, the museum goes into incredible detail about the man and his legacy, ranging from letters and photographs, to even his pistols. The attention to detail can also be found in the neighboring exhibit space dedicated to Ryōma contemporary John Manjiro. Rescued after a shipwreck, Manjuro was brought to the United States, where the knowledge and language skills he acquired made him an indispensable part of Japan’s opening to the West. The images, videos, and hands-on exhibits in the museum’s sunny main exhibition hall bring more context to this tumultuous time. I ascend a set of stairs to the roof, finding even greater context in Katsurahama below, and the entire south coast of Kochi spreading far off, beneath brilliant skies. To Ryōma, this was Tosa, and in its beauty, it is easy to understand the man’s love for it.

I follow a set of neat stone steps through the forest and down to the beach. It is busy with visitors to the aquarium here, with many young couples sitting atop the wall that lines the picturesque crescent beach. This little cove is one of Japan’s more attractive beaches, but sadly no one is allowed to swim. I climb a small set of steps up to the Kaizumi Shrine, known also as the Dragon King Palace, where people prayed for safe voyages and for good catches. The latter apparently applies to romantic catches as well, as many of those offering prayers this day are young women. I too offer a quick prayer to give thanks that my own journey has proven a safe one, but I have one last visit to make.

Sakamoto Ryōma doesn’t notice my approach, his gaze focused on the sea, on the West, on the future. First built in 1938, this statue reached its current height of eight meters in 1999. Ryoma stands in the pose well known from his iconic photograph, leaning casually on a podium, hands tucked into his traditional clothing in a manner somewhat Napoleonic, yet his Western shoes a hint of what direction his footsteps were leading. From here, I’d need to follow them to Kyoto, as there is where his story continues, and ultimately, ends.

Based in Kyoto, Edward J. Taylor’s work has appeared in The Japan Times, Singapore Straits Times, Kyoto Journal, Skyward:JAL’s Inflight Magazine, Resurgence, Outdoor Japan, Kansai Time Out, and Elephant Journal, as well as in various print and online publications. He is a writer for Lonely Planet’s Experience Japan and serves as a Contributing Editor at Kyoto Journal. Co-editor of the Deep Kyoto Walks anthology, Edward is currently at work on a series of books about walking Japan’s ancient highways.

http://notesfromthenog.blogspot.jp/