AH, THE 24-HOUR CONVENIENCE STORE! Shining through the night, a beacon to the hungry, the lonely, the magazine-obsessed. As a person almost always fitting the first category, and too frequently the second, I stopped at the neighborhood 7-Eleven conbini on my way home nearly every night. It became a strange little ritual. Each night I could shed my mousy English-teacher-in-Japan existence with fellow worshippers at the altar of consumer goods—wild-haired teens reverently reading manga, salarymen contemplating the microwave dinners. My own devotional objects were the rows and rows of gleaming, fantastically pack aged junk food. Wasabeef? How fascinating—beef and wasabi flavored potato chips. The excellently named Crunky and Collon. Puffy green soybean-y items with plum flavor. Rows of Pocky, too many varieties to count, an array of drinks to boggle the mind. I felt at peace, surrounded by infinite possibilities.

But the human mind is always intent on losing paradise. It started as I was looking for a certain peach-flavored drink that had taken my fancy. It was gone. There was Supli, many flavors of ever-chalky Calpis, Pocari Sweat…but no peachy deliciousness. After a tiring quest to all the conbinis in my path, I came up empty-handed. This would happen over and over—I would take a shine to something else, and then they would disappear. I finally figured it out as I examined the “spring” version of a drink. They were doing it on purpose, the marketing gods. They were holding out tidbits, only to snatch them away later, when the “season” was over. I was deeply, profoundly pissed off—there is nothing like smacking up against the finite when one had illusions of unlimited potential.

I was used to the merry-go-round of holiday products in the United States—the sickeningly sweet Cadbury’s Creme Egg of Easter, the cranberries of Thanksgiving, the Christmas chestnuts. The Japanese addition of “season” onto holiday made it much worse, however. And then there was the revved-up pace of fads. One year, nata de coco, that glistening, toothy delight, had gripped desserts and and drinks everywhere. The next time I looked around, it had vanished, lost to the black hole of former favorites. In the United States, we rake a little more time with our fads—frozen yogurt lasted for a good five years, and bagels rage on. When a craze ends, it isn’t annihilated from the culinary landscape with such ferocious efficiency; there is still a branch of The Country’s Best Yogurt right outside my workplace.

In Japan, I resisted. I mounted a campaign of denial, pestering the hapless boys at the counter. I hit up my students for any leads they might have. I became a whirling dervish of avarice, of desire. But I slowly became aware that I wasn’t enjoying myself anymore—I had lost my weird little inner sanctum and replaced it with a panting, fruitless search for goods. I railed at the hyper-marketing and threatened to stop my daily pilgrim ages to the conbini. Clearly, it was time to reassess.

As I brooded at home, I remembered the pleasures of fruit seasons in Thailand—the delights of waiting, anticipation, fulfillment. Once, I nearly missed mango season. I arrived in Thailand to see my grandmother eyeing the sole mango in her tree. Every morning, she would examine it. “Not quite yet.” And when she finally deemed it ready, yanked it out of the tree, and peeled it for me, it was pure heaven. All the sun it had grown in, the concentrated longing, the sheer singularity of it bathed me in bliss.

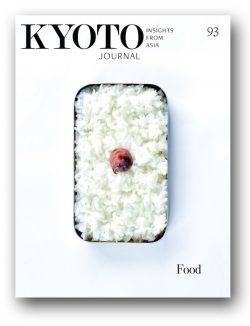

I tried to employ the same thinking to Japanese junk food. I wouldn’t hoard, I wouldn’t traipse in search, I wouldn’t fall prey to fake seasonality, or become attached to a fleeting thing. Instead, I would concentrate on savoring, relishing, and appreciating, with full knowledge of its impermanence. And for the most part, it worked. I could cherish a holiday food calmly, without feeling like marketing forces were yanking my chain. The racks of snacks regained their joy. True, there wasn’t the same sense of limitless choice, of junk food stretching out to an endless horizon. But there was something even better—the sense of precious infinity held in each bite.

Noy Thrupkaew is a freelance writer based in New York City who writes on topics ranging from international affairs to feminism to popular culture and the arts. Her work has appeared in outlets including New York Times, The Washington Post, The Guardian, National Geographic, The Nation. She presented the TED talk, “Human Trafficking Is All Around You: This is How it Works.”