Slowly, as the summer light faded, they came, singly, in pairs, in groups, the young men of Fuchu. They came from the lanes and country roads leading into town, joined others at streets and avenues, then marched abreast, past the high school and town hall. Like rivulets trickling into creeks, then merging to form a river, the young men of Fuchu streamed into the center of town, where the shrine was.

The setting sun cast their shadows far ahead. The men were barefoot, wore only loincloths and sometimes a towel twisted around the head to keep the sweat from falling in their eyes. For this was a Shinto ritual toward which they were moving, a ritual that purified, and here one must be naked.

This was the famous Yami Matsuri of Fuchu, the Festival of Darkness, and it occurred once a year late in the summer. All the young men from this town outside Tokyo and the surrounding countryside came walking through the dying light, making for the central shrine where the great kami, deity of darkness, waited.

I too had wanted to join in, curious — had read about it, asked around, and now, having parked the jeep just outside town, was following the naked men, their numbers growing as street turned into avenue. Soon we were too many for the sidewalks, were walking down the middle of the asphalt toward the shrine, somewhere ahead of us.

The shops, the homes were already lit and people stood and stared at all these men and me, the only one in clothes, while we paraded past. As our numbers swelled, they retreated to watch from open doorways, windows. And I, among the crowd, became aware of the odor of those around me: a clean smell — of rice, and skin.

They in turn were aware of me, a foreign object in their midst. But they were also busy, intent upon the coming rite, and so a glance or two was all I received — no words at all, no questions as to what I was doing there.

I was there because I wanted to see, to experience, for myself. This was why I had driven far into the countryside and found the place, and why I was now one of them, walking through the dusk as though I knew where I was going.

But I did not need to know. The press was now so great that I was going wherever it went. There was no stepping aside, much less turning back. I was caught in this flowing river, surrounded by men who knew where they were going. Our shoulders touched as we walked, our hands collided as we swung our arms.

The sky had deepened, and all at once it was completely dark. Nine o’clock, and someone had pulled the main switch at the power station. This was the signal, the ritual had begun.

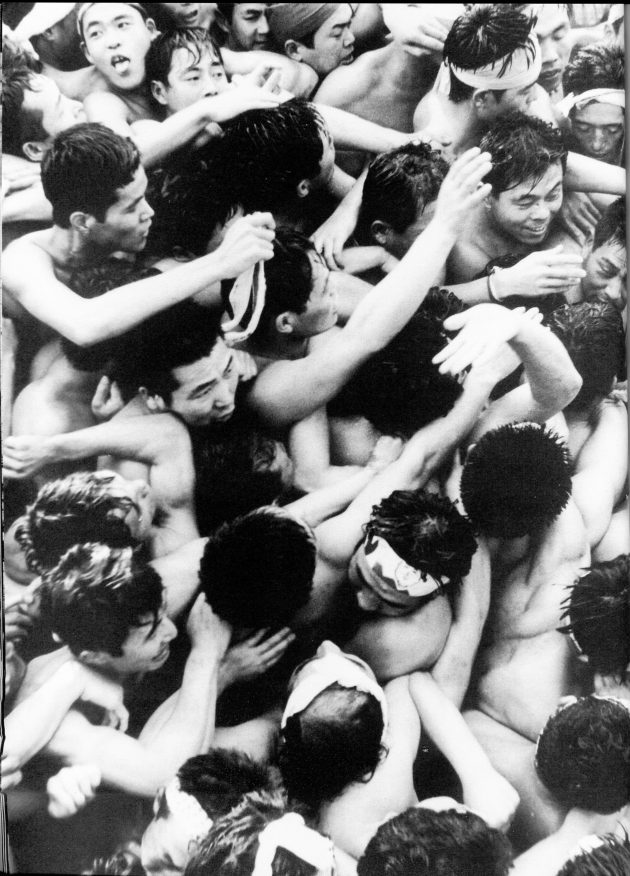

Even with eyes closed I would have known. With the instant black there was a sudden tension, like the stopped-short intake of a breath. No sooner had this jolted, body to body, throughout these hundreds than the march became a jostle.

Pushed, I lurched to one side, then the other. Those behind pressed with their hands to move me faster, and I found my palms against the bare flesh of those in front. The walk turned into a ragged trot and from blindness I returned to sight — a partial night sight, with the white of loincloths in front and, farther off, glimpsed through black trotting bodies, others as though phosphorescent in the night, and above and beyond them the summer stars.

All else was sound and smell. I saw nothing of the sudden hand that struck my side, the bare foot that heedless trod on mine. I felt flesh now close, and smelled it and heard its slap as all of us ran forward, blind, into the night. My shod foot came down, hard if innocent, and I heard the jerk of breath, the exclamation choked, cut off.

There was then a sudden tightening of all these limbs, as torsos crushed together like cattle roaring though a gorge, and I looked up and saw against the sky the great black beam passing overhead. It was a torii, a shrine gateway we were passing through. Then, a blacker darkness, overhanging on either side like cliffs — perhaps rows of cypress, cedar, the outskirts of the shrine.

And now a sound was growing. Jostled, hands before me, palms out, fearing collision, fearing falling, I heard it as a growling coming nearer as we raced along. But I was wrong — it was us.

It was the festival chant, heard when pulling the great wheeled float or shouldering the omikoshi, but now — no longer redolent of effort — it was pure sound, like surf, like wind in the pines. Yu-sha, yu-sha, yu-sha — repeated endlessly, a chain of sound on which we moved, our steps running to its beat. It was all around, filling my eyes and nose as well as ears. And then I heard it deep inside me. It was coming from myself as well.

Possession. We were all possessed by this deity toward whom we were rushing. Chanting, I recalled what I had heard. A Shinto deity and thus without features, name, or disposition — simply a kami like the myriad others — this one, however, retained a quality. He — the gender seemed inevitable — liked darkness. Just as the sequestered kami in the carried omikoshi loved to be jostled and jerked about, tossed and turned, so this god adored the dark and all that happened there.

Abruptly, there was a sharp wrench, a fracture in our chant as though a windpipe had been seized, and the crush was suddenly so great that I was lifted off my feet. We were passing through a narrower gate, I guessed, and into the compound of the shrine itself.

Then there were cries from up ahead and the sound of scuffles, and the chant was broken off; the bodies about me pressed hard into mine, and our whole enormous mass rolled to a halt.

We were in the shrine and from its other gates had pushed in gangs as large as ours; we had collided as we had for generations past, and those left outside were still pushing, pushing their way inside.

I had, I now realized, lost both shoes. My shirt was open, buttons torn away, and I was so flattened against someone’s back that we seemed fused together.

At the same time I suddenly heard the silence. It was as startling as any noise. Utter darkness; complete silence. I moved my head away from it as one moves back from a too bright light. But it was not the silence of solitude, though just as complete. It was vastly peopled, and in it I was slowly being crushed by all these bodies. And the pressure became greater and greater as those outside forced their way in, fighting to join the swarm, to become one with it.

While I could see in the phosphorescent dark, while I too could chant and run with the rest, then I had been exhilarated. But now in the sudden grip of alien skin and muscle, beginning to feel the sweat seeping out of me, sensing the seams of my clothing pulling, then giving with the strain, I became afraid.

What was I doing here in the midst of all these strangers? — a different race, animated by different thoughts and different feelings. Perhaps they could tolerate such barbarous ceremonies as this, but not I. I must escape. There must be some way out of this solid multitude. I thought of Tokyo, of the jeep. And in a few hours I was thinking of home, America.

For in these hours there had been no movement, none was possible. The only sensation was the gradually steadying pressure which now made even breathing hard. That and the few small shifts that occur when water freezes, when a plant expands. The body next to mine had suddenly found a way to turn, a movement as sudden and as meaningless as a bubble of trapped air rising swiftly to the surface.

My imprisoned hands were now part of someone else. Moving my fingers, I felt warm, damp flesh — someone’s back perhaps. Behind me a thigh shifted. Then a weight on my shoulder, the quick fall of a head — the man beside me — as though it had been severed, or as though the man had died, crushed to death, upright.

There we stood, rooted like trees. And I was terrified, seeing myself trapped here forever. There was no pushing my way free, no climbing over heads and shoulders or crawling between legs to find a way out. To sink to the ground could only mean a final, hopeless fall.

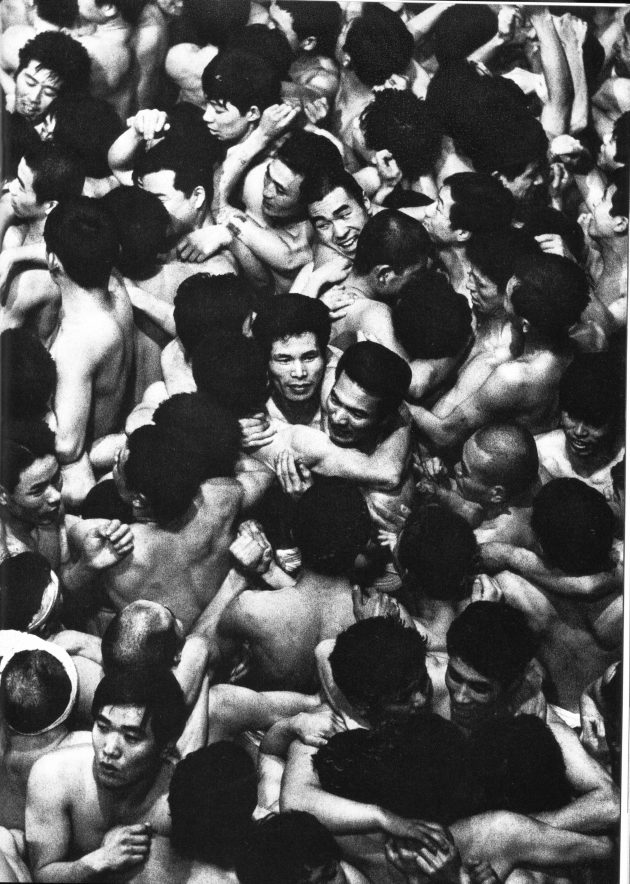

Thus my imagination gripped me. But since there was truly no escape, I just stood there and, with the other trees, endured. Then, as the hours passed, I felt rather than heard a new chant — low, soft, rhythmic, a measured breathing. With it came, at first almost indiscernibly, a gentle movement, as though this packed and standing forest was being swayed by a distant breeze.

As the chant gained, the swaying grew. Damp, hard limbs, a hip perhaps or a shoulder, rubbed me like a branch. And as the night deepened, we chanted —yu-sha, yu-sha, yu-sha.

I felt my fear depart. It lifted slowly and I thought no more about our differences. We were now a single mass crammed into this narrow vessel, and there was no telling us apart.

Cradled, we were slowly merging. This I knew, looking up at the dusty stars, losing all feeling in arms, in legs, smelling the hot rice odor which was now mine as well. I, the man I thought I knew, was gone, become a thousand others. I let my head drop.

It fell across a shoulder or a neck and I realized that I was floating. My feet were no longer on the ground. The pressure had pushed me up. and I was being held aloft by this tight network of bodies, swaying but supporting.

There was no more fear of falling. For the first time I no longer fought for my inch of earth. I lay back and with this came support as more and more of those swaying bodies accepted more and more of me. Or so I felt. But at the same time I knew, an ear suddenly against my cheek, that I was in turn supporting them. And then . . .

And then, I suppose, I must have slept. The deity had had his way with us. His darkness had made us one. Perhaps we all slept, slung in the air, soles off the ground — whole thousands levitating.

I remember only, after a long, long time, raising my head and seeing that pale glow which is earliest morning. Seeing also the breathing profile of the boy asleep beside me, turning and looking deep into his armpit, for his arm was flung about my neck. And I shut my eyes again, not wanting to move, to wake up. I shut my eyes as one pulls the covers over one’s head, unwilling to rise.

What had terrified me now consoled me. How secure, how safe, how warm, those bodies molding mine, those several near, those hundreds farther off. This was as it should have been. Like cells we were within a single form, all breathing, all feeling together. And now it was being alone I dreaded — once more, exposed.

Yet, one by one, all of us were waking up. And those at the farthest ends, whole miles away it seemed, were now stumbling off; slowly the pressure was growing less. I was standing on the ground, the earth strange against my soles, and shortly I could turn and even stoop to retrieve parts of my trampled clothing, the jeep keys still there in the pocket, safe.

The man in front whose back I knew so well stirred and turned. The man behind released me, his flesh becoming separate. The boy whose armpit I had studied was now a plain farmhand who gave a sleepy smile, turned to look for his lost loincloth, searched, gave up.

Then, completely naked, or with dirty loincloths newly tied, or, in my case, the rags of a shirt and most of a pair of trousers, we moved slowly away from each other and out into the brightening day.

We walked, stumbled, streaked with sweat, with dirt, as though newborn and unsure on our feet, as though our eyes, blinded by the dark so long, were not fully opened. There was no smell — except for that of urine, pungent, but not unclean. And now I could see, revealed in the gaps in the thinning crowd that we were making for the font, the great stone urn in front every shrine, where we could drink.

When my turn came I pushed my whole head into that cold holy water, taking great gulps as though I were breathing it, came up dripping and the farmboy led me off to a veranda.

There, on the edge of this large but ordinary shrine, we sat uncovered in the morning light, and watched the others, al1 comrades, ourselves, vanish into the empty streets, each alone, silent, surrounded now only by space.

I felt lost, as though my family were deserting me, as though the world were ending, and when an old priest in his high lacquered hat came by, saw the white foreigner, stopped, surprised, then smiled, I asked: And is the kami happy?

He nodded, affirmed. The kami was happy.

It did not occur to me to ask, as it certainly would have twelve hours before, just what this ceremony was all about anyway and why we should stand there all night and why nothing had happened, or had it?

And so we sat there, recovering, and the priest with his link acolytes, either up early or up all night, brought us small cups of milky ceremonial sake; and the farmer’s son, whose raw young body I knew as well as I knew my own, turned with a smile, not at all surprised that I spoke, and asked me my name.

I told him, then asked his. He told me. What was it? Tadao . . . Tadashi? Nakajima . . . Nakamura?

But before long the sun was up, the streets were emptying. Cleansed, tired, staggering, satisfied young men were going off by the hundred, their shadows long behind them. And I found the jeep just as I had left it, and was surprised that the engine turned over — that the gasoline had not evaporated during my century asleep — and drove back to Tokyo, disheveled, content, at peace.

Over the following year I often thought of this experience. And of the single person it had somehow become: Tadashi Nakajima . . . was that his name? Somehow it now seemed to belong to the whole experience, it was the name of everything, of everybody.

And a year later I went back, not because of young Tadashi, whose face I had quite forgotten, whose very name was blurred. No, because of this experience and what it had meant to me.

But it was 1947, and already the local authorities were cleaning things up. Such relics as the Yami Matsuri did not look right in this new and modern age. Barbaric they seemed, and it couldn’t have been good for the health of those poor boys jammed together in the shrine all night long.

So hundreds of years of history were brought to an end, the chain of generations severed. The Festival of Darkness was stopped — I had attended, become a part of, the very last.

Oh, Fuchu still has a Yami Matsuri of sorts — even now fifty years later — but it is not the real one and the kami is not, I believe, happy. This god is happy only when people return to their real state, when humans again become human, when we are as we truly are. And this can occur only in darkness and in trust.

This article appeared in KJ 44, published in July 2000, together with Donald Richie’s ‘Sacred Desire – notes on Tamotsu Yato: Photographer’ and Yukio Mishima’s ‘On Nakedness and Shame,’ together with 25 pages of Tamotsu’s photographs. Reprinted in issue KJ44 from Private People. Public People (original title Different People) with the kind permission of Kodansha International.

Donald Richie (1924–2013) first came to Japan while serving with the US military in 1947. Fascinated by Japanese culture, he became well known for his writings on Japan spanning 50 years, especially on Japanese cinema. His more than 40 books include The Inland Sea, and Public People, Private People, and two collections of essays on Japan: A Lateral View and Partial Views. The Donald Richie Reader. The Japan Journals: 1947-2004 was edited by Leza Lowitz.

Photographs by Tamotsu Yato.