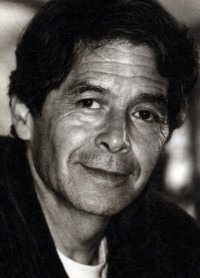

I first met Siao Weijia by chance in the Great Hall of the People at a performance of Swan Lake. We have girls of about the same age and they became fast friends, as only five-year-olds can, during the long intermissions which gave them the chance to run around the cavernous, red-carpeted halls of China’s greatest theater. Thus we met through our kids, briefly exchanging greetings. Mr. Siao is an informal but distinguished looking man, with the air of a musician or artist. At first I thought he was French, and our conversation ground to a halt because of his limited willingness to speak English. Then I discovered he spoke fluent Chinese. He fell into a rapid flow of speech and I remember thinking to myself, ‘This guy speaks Chinese awfully well for a foreigner.’ We agreed to meet again, if only for the kids’ sake, which led to a series of meals and home visits. From the start we discovered a shared interest in talking philosophy and art — infused with politics, as is often the case in China. The casual, conversational interview below took place in the Siao family home in Beijing on January 14, 2003.

I first met Siao Weijia by chance in the Great Hall of the People at a performance of Swan Lake. We have girls of about the same age and they became fast friends, as only five-year-olds can, during the long intermissions which gave them the chance to run around the cavernous, red-carpeted halls of China’s greatest theater. Thus we met through our kids, briefly exchanging greetings. Mr. Siao is an informal but distinguished looking man, with the air of a musician or artist. At first I thought he was French, and our conversation ground to a halt because of his limited willingness to speak English. Then I discovered he spoke fluent Chinese. He fell into a rapid flow of speech and I remember thinking to myself, ‘This guy speaks Chinese awfully well for a foreigner.’ We agreed to meet again, if only for the kids’ sake, which led to a series of meals and home visits. From the start we discovered a shared interest in talking philosophy and art — infused with politics, as is often the case in China. The casual, conversational interview below took place in the Siao family home in Beijing on January 14, 2003.

[T]he Siaos live in a well-known building on Changan Boulevard built in 1978 to house some of the more high-profile victims of the Cultural Revolution, such as Wang Guangmei (wife of Liu Shaoqi, former first lady of China) and the once-outspoken Panchen Lama, both of whom had spent time in prison under the Gang of Four.

I had once been in this unique building in 1983 visiting friends of friends, and at the time was introduced to a lively old lady, a German photographer named Eva who had married Xiao San, an old comrade in arms of Mao Zedong. Eva was well known as one of a handful of Europeans who had become a Chinese citizen, a distinction that came at a high price, as she came under suspicion for her foreign birth and was imprisoned in the Cultural Revolution. Remarkably, she never wavered in her dedication to China and, like many of her Chinese peers who had been to hell and back, remained good humored and faithful to China even after her long ordeal.

Distracted by the happy sounds of my daughter and Siao Weijia’s jumping up and down, singing and playing, it took awhile for it to dawn on me that I had been in this very apartment long before, and that the father of my daughter’s friend was the son of Eva and Xiao San — “Siao” being an older way of romanizing the surname Xiao. We shared a good laugh at the discovery that I had been a guest of his mother’s without realizing it, and thus embarked on a half-day chat about other coincidences, cultural identity, mutual friends and the sudden and unexpected turns of fate that bring one full circle, or full circuit of the spiral, into synchronicity with earlier periods of existence.

In terms of struggling with Chinese identity, I have something in common with Weijia’s European mother and he with my Eurasian children, for the experience of being born Chinese, or of one Chinese parent, is very different from voluntarily adopting China as home. And the week we met, Siao Weijia became a grandfather; his son’s son was born in Beijing Medical Union hospital where my son had been born a few months earlier.

The first framed picture I noticed on the living room wall in the Siao home looked like a Kyoto Journal cover — in fact I had never seen it before but I felt as if I had. This led to the discovery of a shared interest in Zen, though for Siao Weijia, the Japanese manifestation was less interesting than its Chinese roots, namely Chan Buddhism.

Talking to Weijia, who also goes by the name Viktor, I was struck by how his bicultural experience was at once almost painfully unique and at the same time so familiar and universal. Hearing him speak about growing up half-Western in China, growing up different, tackling Chinese language, social mores and yes, prejudice, resonated with my own some twenty years in Asia. The advantages and disadvantages of being different, the frustration of the stigmatized individual wanting to be part of the group, the little indignities, the hidden fonts of pride; it all rang familiar and true.

From the time of Marco Polo, what waiguoren, what scholar, what tourist even, has not felt the seductive tug of wanting to be or wondering what it would be like to be a member of this great ancient civilization. Indeed the compelling charm of this cultural community helps explain why nearly one-fourth of mankind are ready, willing and proud to say, “wo shi zhongruoren, I am Chinese.” Being Chinese is not just a matter of identity, a tick on an immigration card; in China it comes close to being a religion. It’s a way of life, and not an easy one for the native born, let alone late arrivals.

The duality of differing cultures, the dialectic of constant flux, the necessity to strike a balance, to accept things that cannot change, to harness the forces of yin and yang, to master, revel and take joy in the push and pull, are all vital, dynamic forces that Weijia/Viktor, a Russian-speaking Chinese, his father from Hunan, mother from Germany, has been privileged and cursed to deal with constantly in his life. As he explains below, he was from a young age forced to deal with matters some people never even think about.

Listening to a veteran of cultural adaptation and assimilation, a European who can pass as Chinese, a Chinese who can pass as European, I could hear echoes of the gaijin experience in the broadest sense of the word, the story of an outsider trying to get in, the story of an insider trying to get out.

“I always liked painting,” says Siao Weijia, lighting the first of many cigarettes this afternoon, sitting in an armchair that makes him look almost childlike despite the gravitas of his weathered face and gray-streaked locks. “But I got into it by accident.” As his gracious wife, an accomplished potter trained at Jingdezhen, silently serves tea and oranges, he talks about his early interest in painting, then moves on to the movies and music. His mother was a photographer; her brother, whom he never knew, a conductor, and art and music were always part of life in the Siao home.

When he graduated high school in the early 1960s, he says, film seemed like an exciting field to go into — it was the thing to do. He could combine his love of art and music. But nothing turned out as planned; not for him, not for China. The first detour along the way in his personal journey was a chance encounter with an enigmatic artist.

“This guy comes up to me on the street, in Wangfujing, you know, the busy shopping street, and he can see that I look different from other Chinese, he’s a sculptor from the Institute of Fine Arts, he asks me if I would model for him. Well, I don’t know if you realize this, but in China at that time, even young people, you couldn’t just give your address to strangers, especially my family; my father was well-known, he was a friend of Mao, so our address was like a state secret. So we talked awhile, the guy told me he was sick of drawing Han Chinese faces, he liked sketching minorities and he knew the minute he saw me that I was different, though he didn’t know exactly what I was. Anyway, we talked and that was it. We didn’t exchange any personal information. I never thought I’d see the guy again, and then a few weeks later he shows up at my door. Even now I don’t know how he tracked me down, but maybe it wasn’t that hard because I looked different. Anyway, we ended up becoming fast friends, and he’s now a renowned sculptor living in Texas, but back then, in 1962, he arranged for me to audit classes at the Institute for Fine Arts.

“Although I never modeled for him, I was the first subject of another important artist,” Siao says with a mischievous smile. “Willy Wong, he drew a cartoon picture of me and then went on to be a famous cartoonist.”

“Well, I didn’t stay in Beijing much longer after that because of my girlfriend. She was studying drama, Stanislavsky and all that, which I knew about from my Russian education. She and I started dating when I was in high school, she was already working in the theater, the Central Drama Troupe of China ( xijuxueyuan.) I was actually older than her, my education all screwed up from my years in Moscow, so when I came back to China at age twelve, I couldn’t read or write Chinese and they put me in a class with little kids, even though I was already fluent in Russian and fond of reading literature. It wasn’t so bad, there were other older kids, you know it was just after the revolution and many things were in flux, many people had their education interrupted. I guess I had a lot of learning to do; I didn’t graduate high school until I was 22.

“Learning to read and write Chinese was easy; the hard part was trying to fit in. Ever notice how Chinese go all over the world and adapt to the language and culture, but foreigners come here and remain isolated? Well, I think Chinese society is the toughest thing to adapt to, it’s ten times harder than the language.

“My father, a very busy man, rarely had time to play with us kids, but one time he takes me to the old Peking Opera house, and we sit there doing nothing for four hours. Four boring hours, and he was usually so busy. I couldn’t believe it. And the music was so bad, it was like hearing dogs barking and donkeys braying and the story was opaque and indecipherable. The actors in these strange costumes made such a fuss just to say one line or walk a few steps. Peking Opera was especially hard for me to take after being steeped in the great operas of the Western tradition, where the story was always clear and the music so familiar, so classical. But with time I learned that Peking Opera, like any opera, is a language in its own right, and the only thing wrong with it was me. I didn’t understand it. Even today I’m not a big fan, but at least I can appreciate what they’re trying to do and I tell you, it’s quite sophisticated.”

Siao’s wife pours a fresh round of tea and we nibble on oranges.

“So anyway I was dating this woman, going to all her rehearsals, I just loved music and theater, and it’s obvious I’m different and her father didn’t like that. He was a regional communist boss in Changchun, in Manchuria at the time, in Harbin. He found out who my parents were and banned her from seeing me. Even as early as ‘62, the discrimination against Chinese with foreign connections was starting to kick in, though it got much, much worse in the Cultural Revolution.

“Her father orders her to the northeast, hundreds of miles from Beijing, so what did I do? I went to Changchun to be near her. I landed my first job teaching Russian at a college there even though I hadn’t gone to college myself. I was fluent in Russian and the language was in demand. Although there had been a break between the USSR and China which started with Khruschev — oh how we hated Khruschev!— it was viewed as a political falling out, while Russian culture, literature, music, etc. were still very much appreciated.

“She and I eventually married and had two sons. We spent much of the Cultural Revolution on my campus in Jilin in the northeast. One day the authorities came to me and told me my parents had been arrested, but ’don’t tell anyone.’ That was fine with me, I didn’t want people to know my parents were in jail. At first I got along well, like other young people — I had my group, my crew, and I know it’s hard for outsiders to believe this, but we had a high degree of free speech during the Cultural Revolution. Of course, we stuck to our own factions, but we trusted one another and we were always talking politics, trying to figure out what was going on.

“Our in-group solidarity was really strong. It was only later on, when we were broken up and isolated, that some forced betrayals took place, and you don’t really blame that on people if you understand the situation they were in.

“Then one day they tell me I’ve been kicked out of the university, just like that. So I went to the nearest farm commune, asked if I could work there. They examined my file and decided no, I was of suspected background and did not deserve to be a farmer. So I wandered around, finally went back to Beijing begging to do work, any work. I did not look down on manual labor, I would have gladly done it, but I was in limbo, not allowed to do anything for a while.

“I think my attitude toward manual work was different from some of my peers because I had attended an orthodox workers’ school outside Moscow where the working class was considered the highest expression of Marxism. It was never really like that in China, especially among my Chinese schoolmates, who claimed to be communist but had an abhorrence for manual labor. I remember pulling a heavy load on a rickshaw bicycle on Wangfujing, and all these foreigners were looking at me, saying ‘poor Chinese’ or something like that and I didn’t feel that way at all. I was proud to be doing manual work and proud to be Chinese.

“After returning from the Soviet Union in 1952 at age twelve I didn’t have much contact with Russians even though I was fluent in the language. They tended to be clustered in two places, the Soviet embassy compound (the largest embassy grounds in Beijing, the only one located in the prestigious downtown area inside the Second Ring Road) and the Friendship Hotel (a leafy compound built to house Russian experts, later a hotel for foreigners in general).

“But I had all these Chinese friends who had lived in Russia and we were like family. We are Chinese but we shared this Russian thing, even today we still enjoy speaking Russian to one another. We really bonded, here it is half a century later and I’m still in touch with many of them — why ,we just had another reunion a few weeks ago. It’s an interesting group: before the revolution, many high cadres spent time in Russia, and some of the kids grew up practically Russian. We share a common sensibility.

“In my group of Soviet returnees there were the kids of top leaders, though we hardly paid attention to politics at the time and didn’t really care who was who. Later on, this got us in trouble, like in the Cultural Revolution you might be accused of something involving Mao and you might honestly say I don’t know anyone in his family. Well, I didn’t learn till 1968 that my friend Jiao-jiao was Mao’s daughter, or that so and so was Zhu De’s kid and so on. (Jiao-jiao’s formal name is Limin, she is the daughter of Mao and third wife He Zizhen, who went to Russia to convalesce after Jiang Qing captured his attention.)

“Since I was born in the revolutionary base in Yanan, and my father and Mao had spent ten close years together, they all knew who I was. But after coming back from Russia, I only saw Mao twice: in 1963 at Beidaihe (my brother asked for his autograph, I thought that wasn’t cool and just hid behind the curtains) and later at Tiananmen in 1966 when Mao put the red armband on my friend’s arm in front of a huge crowd of Red Guards and launched the Cultural Revolution.

“When I think back on my childhood, it was like two cultures, I was European at home and Chinese at school. Because I was different, I got stared at, people made comments, in fact they still do. Even now people say things. ‘Why are they all looking at me like that?’ I used to wonder. At first I kept my head down, ashamed of not fitting in. I used to have to take the trolley to school, there was an east-west line in Beijing, around the time they were building the Great Hall of the People, and you sat riding on these benches facing a long row of people. I realized it wouldn’t do to keep my head bent down forever, so I started looking back. Look ‘em right in the eye, one by one, every single one of them. And then they left me alone.

“It’s funny, my two boys, who grew up here, had different problems. When my eldest went to visit his foreign friends at the Friendship Hotel, the guard wouldn’t let him in because he was Chinese. Now, it isn’t that strict a place, and rules can be broken if only you play the game. The guard could tell my son wanted to go in and he said with a wink, ‘Are you sure you’re not Japanese? Korean?” My son knew this would do the trick but he refused to lie. ’I am Chinese,’ he said and he waited outside. Finally his friends came by and he was allowed in, but I am very proud of him for that.

“Now, when I was in school, I could have gone to the elite high school number 101 where many of the leaders’ kids went, but I chose number 24 which had a tough reputation. I think it was my Russian worker’s education that made me unhappy to discover I was part of the elite. I was really unhappy about it. So I go to the hoodlum school. Hoodlums, not like you have in the States with gangs and violence and all that, but just tough kids. And I’m walking along the sidewalk, and I always made a point of putting my chest out, keeping my head high as a matter of pride. And these guys, three of them together, they bump into me. I wasn’t really paying attention, and thought it was by accident, so I said, ‘ Dui bu qi,’ I’m sorry, sort of like a Russian person would say in a similar situation. My thinking was still foreign in some ways, I didn’t realize yet how hard, how almost impossible it is for Chinese to say, ’I’m sorry.’ Even my daughter Xianxian, she’s only five and it took her a year to be willing to say it. ’Sorry’ is not a word that comes off the lips of Chinese easily.

“So my friend is really worried; he says, ‘Look, they challenged you, bumped you on purpose,’ and at first I didn’t believe him. But then I found out through the grapevine it was true. They were trying to bully me. And the funny thing is, my reaction had scared them because they couldn’t understand it. They were scared of me because I’d said ‘Dui bu qi.’ It took them totally by surprise, they didn’t know how to react, and thought I was so tough I dared make fun of all three of them at once. That’s when I learned that people notice things like how you walk, and at that time, at that school, you had to slump a little bit to fit in. But I just kept walking my way, that’s my attitude.

“Junior high was really tough. I’m this oversized kid who looks different trying to fit in to the most demanding culture in the world. I mean, like I was reading Madame Bovary at home and loved the opera but I was nothing to these kids if I wasn’t Chinese — to get along I had to be just like them. I just couldn’t bring the European side of me to school, and when I saw foreigners, I started to look at them as a Chinese would, with a deliberate distance. But at home my parents would have all kinds of foreigners over and I didn’t think anything of it. My overwhelming worry at the time was I that I understood China but China didn’t understand me.

“So I had to change myself. My crash course in Chinese culture was through literature. It’s amazing, all these kids were quoting ancient classics, making references to Three Kingdoms and Journey to the West and I didn’t have a clue as to what they were talking about. And my Chinese wasn’t good enough to read that stuff, I’m not even sure how they learned it, but I guess it’s just in the culture. So I found Russian translations of the Chinese classics and read them everyday. I came to understand the environment of the other kids, the way they thought and talked, but I can still say they didn’t understand me. I’m not blaming them. Their reactions were normal and predictable. They lived their lives within a limited frame. They simply didn’t have the necessary experience to understand me, but I had no excuse not to understand them.

“Over the years I’ve been called many things. Even now I get called laowai . Around 1949 I was called ‘American.’ For most of the 1950s I was called ‘Soviet’ and then in the mid-sixties when almost all foreigners were gone, I was called ‘Albanian.’ I don’t take it personally, I can stand in their shoes, see what they see. So most of the time I just ignore it, but sometimes, you know, depending on your mood, you can have fun with the situation: ‘What are you?’ ‘I’m handsome.’ Or ‘What are you?’ ‘Since when is Xinjiang not a part of China?’ After which they quickly assume I’m from Xinjiang and get all flustered, but of course they still don’t know the first thing about me.

“In the Cultural Revolution being different could have worked against me but it turned out okay because I was in a contained environment. Since I was different, every last person at the college knew who I was, and that I had a respectable Chinese background, even though I didn’t know who they were. So I didn’t fall under suspicion based on looks, I was a known entity.

“To Chinese, it’s very important to know if someone is Chinese or not, but to me, all that matters is knowing I am human and that this is a human experience. Everyone handles it a little differently I guess. My elder brother, he can act very Chinese if he wants to, but that kind of gives away the fact he hasn’t completely internalized it, he overdoes it, whereas my younger brother was only three when we came back so he’s Chinese in an effortless way. My mother was always a laowai, and she never lost sight of that, but she overcame the obstacles she faced as a white woman in China because of her tremendous optimism: she had such a bright outlook on things. She and my father, married for 48 years, do you realize they were both imprisoned in Qincheng, under the roof of the same prison from 1966-1974 and didn’t even know it? So even there they were together in a way. My father was accused of being a Soviet agent, my mother was suspected of being a German spy, but I never spent a day in jail. You know what’s funny? My mother never spoke Chinese very well, but when she came out of prison she was speaking crack Chinese, I mean really good, but then after that she kind of lost it again.

“There’s so much that is still unknown about the Cultural Revolution. It was really complicated. Later on we heard different things but for most of the time we thought Mao was right, or at worse misled by bad people around him. I never knew anyone who didn’t respect Mao, but plenty of people disliked Lin Biao from the start. It was always my feeling Mao was democratic at heart, he was against corruption, and he hated bureaucratism. And you can find many cases where the Party was going in the wrong direction and he put the brake on things. There was a time some elements in the party wanted to crack down on sex in the countryside and Mao wrote a very funny response, saying you can’t crack down on sex, that’s the one thing no one can control. He also put the brakes on the anti-Rightist movement as prosecuted by Deng Xiaoping, said it’s time to ‘take the hats’ (accusations) off people. He was in many ways a moderate influence in the party. Did you ever hear of the anti- Hu Shih movement? Mao knew Hu Shih was an important historical influence, but it plainly wasn’t in the interests of the party to acknowledge this, so Mao said, ‘Leave it to the historians to figure out who Hu Shih really was. That’s not our job as communists.’

“He also was correct in criticizing corruption and bureaucratic privilege of the Party. But he was wrong in Great Leap Forward, there’s no doubt about that, and that Peng Dehuai’s criticism of him was correct. But China wasn’t ready to take on Mao, just like China wasn’t ready for the overnight change called for at Tiananmen, so they dumped Peng, just like Zhao was dumped after June 4 (1989). Probably one of Mao’s most powerful insights into Chinese political behavior is that you had to keep people busy, pre-occupied, you can’t leave the masses with nothing to do. And Deng saw this too: keep looking and moving forward. In Chinese politics, trying to assign blame for past events brings no good, it can really backfire, creating only more confusion. I think that’s why Deng pressed forward with reform after June 4. And we still don’t know who gave the order to fire on the demonstrators, but it wasn’t likely ordered by Deng. But he had to go along with it. At the end of the day, he saw it was more important to bring about good changes than sort out what was wrong or right.

“As for the Cultural Revolution, I would blame that more on Jiang Qing, Kang Sheng and all them. Mao of course had a hand in starting it but he was too old to stop it, and if he had been younger it might have turned out better. Even he was used. I know for a fact his daughter, my friend Jiao-jiao, was used shamelessly by Jiang Qing. Jiang Qing, who is her stepmother, got very friendly with her at a certain point, and used her for political reasons. I’m telling you, Jiao-jiao is not a political person, she was just being used, but people associated her with the excesses and saw her in the wrong way.

“Mao was deeply respected by my father to the end, I think. Look, even Liu Shaoqi remained loyal to Mao. There was an element of fear, you have to acknowledge that, Mao was so bright and so unpredictable, but respect was the most important factor. Look at Zhou Enlai: he went against Mao several times early in his career, at Jinggangshan liberated base and again on the Long March due to his involvement with Li De (Otto Braun, German Comintern agent assigned to CCP in 1930s) and yet after all that, Zhou fell into role of Mao’s loyal retainer, faithful to the emperor to the last. All the stories you hear about Mao and all the girls, the book on Mao’s sex life written by his doctor, well I’ve talked to two other of Mao’s doctors and they said that guy Li did not have as much access as is claimed, he wasn’t even working for Mao much of that time, and that the book is about 80 percent imagination. It is well-known that many communist officials took a light view of marriage, they saw it as a feudal institution, and there was a lot of mixing in Yanan. But how many girls Mao had is not the point, any more than it is with Kennedy; what matters is how he led.

I think art is like politics: your appreciation changes as you grow. When I was younger, my mother was fond of Picasso and the impressionists, and I just couldn’t see anything in it. In fact, I hated abstract art. Then as I got older and looked at what my brush was producing, I realized it was abstract art. All of a sudden I fell in love with Kandinsky. All of a sudden I discovered I was an abstract artist!

“Nowadays I keep my brushes and worktable ready, but only paint in binges, when it hits me. Doing taijieveryday is my discipline, and it guides my painting as well. When I paint, I depend on the currents in my body and mind to move the brush. I can’t predict the exact result, but the ink on the paper gives a glimpse of my feeling, my force field at that precise moment in time. I was brought up to believe in science but I can tell you there are so many forces we can’t see. Some of them, like electricity, magnetism, gravity, science can deal with pretty well. But what about thoughts? What about the force field of an individual? I know from taiji it is possible to touch without touching, that if you’re really good you can knock someone down without ever touching them. Now the problem is, you should never do this with non-practitioners as you might hurt them, screw them up. And if you stage a demonstration of this power with two advanced practitioners, then people say they’re confederates. But in taiji, the power of qi is real. I think there are people doing aikido who understand that. It doesn’t mean you can move or levitate objects or anything like that, but you can influence another person.

“So this flow, this power, is what I call upon when I pick up the brush. That is the power I try to harness in my life, to develop my biological field. The power to be more sensitive and yet more safe. To project and protect. To interact and be free of interference. There has to be a balance; self-control is part of it. If you open yourself up, but don’t guard yourself, if you overdevelop one side, not the other, you end up in Andingmen Mental Hospital. Balance is critical.

“Everyone has the ability, but if it’s not developed it’s useless. The thing is to find the pulse and follow it ( genzhe jingluo zou ).There are many roads to achieving this. To argue about the path is to miss the point. It’s like climbing a mountain. The guy on the sunny side says it’s best to wear a sleeveless T-shirt, the guy on the shady side says you must wear a coat. But they’re climbing the same mountain, they’re both right in a way. Truth doesn’t flow in a single direction. So they argue but they’re in agreement. There are many valid ways, the main thing is to develop the path that suits you, and to be honest with yourself. The worst thing is to fool yourself. So don’t try to go up by going down or whatever. Harnessing qi through taiji is not a goal, it’s a process, a way of life.

“I think of a painting as a representation of a biological field, a tiny piece of a largely invisible hologram if you will. They capture a bit of time, as time is movement, and without movement there is no time. Just as words are only a tiny approximation of what we’re trying to say, art is just a tiny bit of the picture. In Chinese we say, ‘ hua wai zhi yan’ which refers to the words that go unspoken but nonetheless communicate deeply. Meaning doesn’t exist in words, it exists outside them.”