Isabella L. Bird, with introduction and postscript by Ken Rodgers

Excerpts from Unbeaten Tracks In Japan – An Account of Travels in the Interior Including Visits to the Aborigines of Yezo and the Shrines of Nikko and Ise (1880)

[I]n April 1878, at the age of 47, Isabella Bird was advised to “recruit her health” by travel. “Attracted less by the reputed excellence of its climate than by the certainty that it possessed, in an especial degree, those sources of novel and sustained interest which conduce so essentially to the enjoyment and restoration of a solitary health-seeker,” she made Japan her destination. “The climate disappointed me, but, though I found the country a study rather than a rapture, its interest exceeded my largest expectations.”

She arrived 10 years after the Meiji Restoration (and just one year after the Satsuma Rebellion—historical source of The Last Samurai), when travels by missionaries and traders were limited to within 25 miles radius from the treaty ports, unless they obtained traveling passports for a given time and route. However, she had no intention of lingering among her compatriots in Tokyo, or luxuriating at a hot-spring spa. Inspired by a paper in the Transactions of the Asiatic Society, which mentioned “a most exquisitely picturesque, but difficult, route up the course of the Kinugawa, which seems almost as unknown to Japanese as to foreigners,” she set off for the interior, traveling as far as Biratori, in Yezo (Hokkaido) over 1200 miles by road, her only companion an 18-year-old interpreter, Ito Tsurukichi.

“From Nikko northwards my route was altogether off the beaten track, and had never been traversed in its entirety by any European. I lived among the Japanese, and saw their mode of living, in regions unaffected by European contact. As a lady travelling alone, and the first European lady who had been seen in several districts through which my route lay, my experiences differed more or less widely from those of preceding travellers; and I am able to offer a fuller account of the aborigines of Yezo, obtained by actual acquaintance with them, than has hitherto been given.”

Her book, drawn from letters written en route, to her sister and friends back in Britain, “places the reader in the position of the traveller, and makes him share the vicissitudes of travel, discomfort, difficulty, and tedium, as well as novelty and enjoyment.”

* * *

LETTER VI

KASUKABE, July 10, 1878.

The preparations were finished yesterday, and my outfit weighed 110 lbs., which, with Ito’s weight of 90 lbs., is as much as can be carried by an average Japanese horse. My two painted wicker boxes lined with paper and with waterproof covers are convenient for the two sides of a pack-horse. I have a folding-chair—for in a Japanese house there is nothing but the floor to sit upon, and not even a solid wall to lean against—an air-pillow for kuruma1 travelling, an india-rubber bath, sheets, a blanket, and last, and more important than all else, a canvas stretcher on light poles, which can be put together in two minutes; and being 2.5 feet high is supposed to be secure from fleas. The “Food Question” has been solved by a modified rejection of all advice! I have only brought a small supply of Liebig’s extract of meat, 4 lbs. of raisins, some chocolate, both for eating and drinking, and some brandy in case of need. I have my own Mexican saddle and bridle, a reasonable quantity of clothes, including a loose wrapper for wearing in the evenings, some candles, Mr. Brunton’s large map of Japan, volumes of the Transactions of the English Asiatic Society, and Mr. Satow’s Anglo-Japanese Dictionary. My travelling dress is a short costume of dust-coloured striped tweed, with strong laced boots of unblacked leather, and a Japanese hat, shaped like a large inverted bowl, of light bamboo plait, with a white cotton cover, and a very light frame inside, which fits round the brow and leaves a space of 1.5 inches between the hat and the head for the free circulation of air. It only weighs 2.5 ounces, and is infinitely to be preferred to a heavy pith helmet. I have a bag for my passport, which hangs to my waist. All my luggage, with the exception of my saddle, which I use for a footstool, goes into one kuruma, and Ito, who is limited to 12 lbs., takes his along with him.1

Passports usually define the route over which the foreigner is to travel, but in this case Sir H. Parkes has obtained one which is practically unrestricted, for it permits me to travel through all Japan north of Tokiyo and in Yezo without specifying any route. This precious document, without which I should be liable to be arrested and forwarded to my consul, is of course in Japanese, but the cover gives in English the regulations under which it is issued. A passport must be applied for, for reasons of “health, botanical research, or scientific investigation.” Its bearer must not light fires in woods, attend fires on horseback, trespass on fields, enclosures, or game-preserves, scribble on temples, shrines, or walls, drive fast on a narrow road, or disregard notices of “No thoroughfare.” He must “conduct himself in an orderly and conciliating manner towards the Japanese authorities and people;” he “must produce his passport to any officials who may demand it,” under pain of arrest; and while in the interior “is forbidden to shoot, trade, to conclude mercantile contracts with Japanese, or to rent houses or rooms for a longer period than his journey requires.”

(1) The list of my equipments is given as a help to future travellers, especially ladies, who desire to travel long distances in the interior of Japan. One wicker basket is enough, as I afterwards found. I advise every traveller in the ruder regions of Japan to take a similar stretcher and a good mosquito net. With these he may defy all ordinary discomforts.

***

LETTER XVII

ICHINONO, July 12.

It is a mistake to arrive at a yadoya after dark. Even if the best rooms are not full it takes fully an hour to get my food and the room ready, and meanwhile I cannot employ my time usefully because of the mosquitoes. There was heavy rain all night, accompanied by the first wind that I have heard since landing; and the fitful creaking of the pines and the drumming from the shrine made me glad to get up at sunrise, or rather at daylight, for there has not been a sunrise since I came, or a sunset either. That day we travelled by Sekki to Kawaguchi in kurumas, i.e. we were sometimes bumped over stones, sometimes deposited on the edge of a quagmire, and asked to get out; and sometimes compelled to walk for two or three miles at a time along the infamous bridle-track above the river Arai, up which two men could hardly push and haul an empty vehicle; and, as they often had to lift them bodily and carry them for some distance, I was really glad when we reached the village of Kawaguchi to find that they could go no farther, though, as we could only get one horse, I had to walk the last stage in a torrent of rain, poorly protected by my paper waterproof cloak.

Mr. Brunton’s excellent map fails in this region, so it is only by fixing on the well-known city of Yamagata and devising routes to it that we get on. Half the evening is spent in consulting Japanese maps, if we can get them, and in questioning the house-master and Transport Agent, and any chance travellers; but the people know nothing beyond the distance of a few ri, and the agents seldom tell one anything beyond the next stage. When I inquire about the “unbeaten tracks” that I wish to take, the answers are, “It’s an awful road through mountains,” or “There are many bad rivers to cross,” or “There are none but farmers’ houses to stop at.” No encouragement is ever given, but we get on, and shall get on, I doubt not, though the hardships are not what I would desire in my present state of health.

***

LETTER X

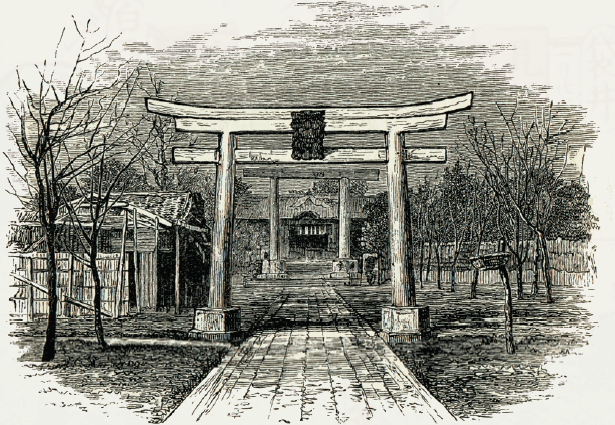

YASHIMAYA, YUMOTO, NIKKOZAN MOUNTAINS, June 22.

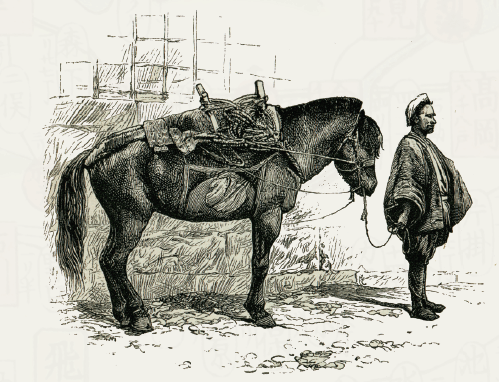

To-day I have made an experimental journey on horseback, have done fifteen miles in eight hours of continuous travelling, and have encountered for the first time the Japanese pack-horse—an animal of which many unpleasing stories are told, and which has hitherto been as mythical to me as the kirin, or dragon. I have neither been kicked, bitten, nor pitched off, however, for mares are used exclusively in this district, gentle creatures about fourteen hands high, with weak hind-quarters, and heads nearly concealed by shaggy manes and forelocks. They are led by a rope round the nose, and go barefoot, except on stony ground, when the mago, or man who leads them, ties straw sandals on their feet.

IRIMICHI, Nikko, June 23.

To-morrow I leave luxury behind and plunge into the interior, hoping to emerge somehow upon the Sea of Japan. No information can be got here except about the route to Niigata, which I have decided not to take, so, after much study of Brunton’s map, I have fixed upon one place, and have said positively, “I go to Tajima.” If I reach it I can get farther, but all I can learn is, “It’s a very bad road, it’s all among the mountains.” Ito, who has a great regard for his own comforts, tries to dissuade me from going by saying that I shall lose mine, but, as these kind people have ingeniously repaired my bed by doubling the canvas and lacing it into holes in the side poles, and as I have lived for the last three days on rice, eggs, and coarse vermicelli about the thickness and colour of earth-worms, this prospect does not appall me!

In Japan there is a Land Transport Company, called Riku-un-kaisha, with a head-office in Tokiyo, and branches in various towns and villages. It arranges for the transport of travellers and merchandise by pack-horses and coolies at certain fixed rates, and gives receipts in due form. It hires the horses from the farmers, and makes a moderate profit on each transaction, but saves the traveller from difficulties, delays, and extortions. The prices vary considerably in different districts, and are regulated by the price of forage, the state of the roads, and the number of hireable horses. For a ri, nearly 2.5 miles, they charge from 6 to 10 sen for a horse and the man who leads it, for a kuruma with one man from 4 to 9 sen for the same distance, and for baggage coolies about the same. I intend to make use of it always, much against Ito’s wishes, who reckoned on many a prospective “squeeze” in dealings with the farmers.

***

LETTER XIV

TSUGAWA, July 2.

Yesterday’s journey was one of the most severe I have yet had, for in ten hours of hard travelling I only accomplished fifteen miles. The road from Kurumatoge westwards is so infamous that the stages are sometimes little more than a mile. Yet it is by it, so far at least as the Tsugawa river, that the produce and manufactures of the rich plain of Aidzu, with its numerous towns, and of a very large interior district, must find an outlet at Niigata. In defiance of all modern ideas, it goes straight up and straight down hill, at a gradient that I should be afraid to hazard a guess at, and at present it is a perfect quagmire, into which great stones have been thrown, some of which have subsided edgewise, and others have disappeared altogether. It is the very worst road I ever rode over, and that is saying a good deal! Kurumatoge was the last of seventeen mountain-passes, over 2000 feet high, which I have crossed since leaving Nikko. Between it and Tsugawa the scenery, though on a smaller scale, is of much the same character as hitherto—hills wooded to their tops, cleft by ravines which open out occasionally to divulge more distant ranges, all smothered in greenery, which, when I am ill-pleased, I am inclined to call “rank vegetation.” Oh that an abrupt scaur, or a strip of flaming desert, or something salient and brilliant, would break in, however discordantly, upon this monotony of green!

***

LETTER XVIII

KAMINOYAMA

As I entered Komatsu the first man whom I met turned back hastily, called into the first house the words which mean “Quick, here’s a foreigner;” the three carpenters who were at work there flung down their tools and, without waiting to put on their kimonos, sped down the street calling out the news, so that by the time I reached the yadoya a large crowd was pressing upon me. The front was mean and unpromising-looking, but, on reaching the back by a stone bridge over a stream which ran through the house, I found a room 40 feet long by 15 high, entirely open along one side to a garden with a large fish-pond with goldfish, a pagoda, dwarf trees, and all the usual miniature adornments. Fusuma of wrinkled blue paper splashed with gold turned this “gallery” into two rooms; but there was no privacy, for the crowds climbed upon the roofs at the back, and sat there patiently until night.

When I left Komatsu there were fully sixty people inside the house and 1500 outside—walls, verandahs, and even roofs being packed. From Nikko to Komatsu mares had been exclusively used, but there I encountered for the first time the terrible [male] Japanese pack-horse. Two horridly fierce-looking creatures were at the door, with their heads tied down till their necks were completely arched. When I mounted the crowd followed, gathering as it went, frightening the horse with the clatter of clogs and the sound of a multitude, till he broke his head-rope, and, the frightened mago letting him go, he proceeded down the street mainly on his hind feet, squealing, and striking savagely with his fore feet, the crowd scattering to the right and left, till, as it surged past the police station, four policemen came out and arrested it; only to gather again, however, for there was a longer street, down which my horse proceeded in the same fashion, and, looking round, I saw Ito’s horse on his hind legs and Ito on the ground. My beast jumped over all ditches, attacked all foot-passengers with his teeth, and behaved so like a wild animal that not all my previous acquaintance with the idiosyncrasies of horses enabled me to cope with him.

LETTER XIX

KANAYAMA, July 16.

Shinjo is a wretched place. It is a daimiyo’s town, and every daimiyo’s town that I have seen has an air of decay, partly owing to the fact that the castle is either pulled down, or has been allowed to fall into decay. Shinjo has a large trade in rice, silk, and hemp, and ought not to be as poor as it looks. The mosquitoes were in thousands, and I had to go to bed, so as to be out of their reach, before I had finished my wretched meal of sago and condensed milk. There was a hot rain all night, my wretched room was dirty and stifling, and rats gnawed my boots and ran away with my cucumbers.

***

LETTER XXV

TSUGURATA, July 27.

Three miles of good road thronged with half the people of Kubota on foot and in kurumas, red vans drawn by horses, pairs of policemen in kurumas, hundreds of children being carried, hundreds more on foot, little girls, formal and precocious looking, with hair dressed with scarlet crepe and flowers, hobbling toilsomely along on high clogs, groups of men and women, never intermixing, stalls driving a “roaring trade” in cakes and sweetmeats, women making mochi as fast as the buyers ate it, broad rice-fields rolling like a green sea on the right, an ocean of liquid turquoise on the left, the grey roofs of Kubota looking out from their green surroundings, Taiheisan in deepest indigo blocking the view to the south, a glorious day, and a summer sun streaming over all, made up the cheeriest and most festal scene that I have seen in Japan; men, women, and children, vans and kurumas, policemen and horsemen, all on their way to a mean-looking town, Minato, the junk port of Kubota, which was keeping matsuri, or festival, in honour of the birthday of the god Shimmai.

Dismissing the kurumas, which could go no farther, we dived into the crowd, which was wedged along a mean street, nearly a mile long—a miserable street of poor tea-houses and poor shop-fronts; but, in fact, you could hardly see the street for the people. Paper lanterns were hung close together along its whole length. There were rude scaffoldings supporting matted and covered platforms, on which people were drinking tea and sake and enjoying the crowd below; monkey theatres and dog theatres, two mangy sheep and a lean pig attracting wondering crowds, for neither of these animals is known in this region of Japan; a booth in which a woman was having her head cut off every half-hour for 2 sen a spectator; cars with roofs like temples, on which, with forty men at the ropes, dancing children of the highest class were being borne in procession; a theatre with an open front, on the boards of which two men in antique dresses, with sleeves touching the ground, were performing with tedious slowness a classic dance of tedious posturings, which consisted mainly in dexterous movements of the aforesaid sleeves, and occasional emphatic stampings, and utterances of the word No in a hoarse howl. It is needless to say that a foreign lady was not the least of the attractions of the fair.

The police told me that there were 22,000 strangers in Minato, yet for 32,000 holiday-makers a force of twenty-five policemen was sufficient. I did not see one person under the influence of sake up to 3 p.m., when I left, nor a solitary instance of rude or improper behaviour, nor was I in any way rudely crowded upon, for, even where the crowd was densest, the people of their own accord formed a ring and left me breathing space.

Unbeaten Tracks can be

found at gutenburg.com, and archive.org. Also published in Japanese—originally translated

by Ito Tsurukichi—it was recently adapted into a highly “moe-fied”

manga, Fushigi no Kuni no Bird, by Sassa Taiga, available online

in a fine “scanlation”:

www.mangakakalot.com/

manga/fushigi_no_kuni_no_bird