Place can take hold of us in ways that defy expression, the soul of course having its own language. The moment I read about the Kumano Kodo, the journey began. The Kumano region was long considered to be one of the most sacred regions in Japan, its three shrines attracting pilgrims so numerous that they were said to resemble a line of ants. But it was the yamabushi that truly intrigued me, these mystical and mysterious beings practicing their Buddhist and Shinto-tinged mountain rites high in the peaks above. I’d walked some sections over the years, and in my fifteenth year in Japan I decided to walk the rest. Ever the purist, I tried to be faithful to the way the Heian period pilgrims undertook the pilgrimage. Barred access to ox-cart or palanquin, my wife Miki and I instead walked from our home in Northeastern Kyoto to the confluence of the Katsura and Uji Rivers, then followed what is now called the Yodo, upon which boats used to carry the pilgrims toward the city that eventually became Osaka…

…We pick up the Kumano Kodo, (here still called the Kyo Kaido) at the base of Otokoyama. Leaving the road, we follow a quiet forest trail toward Iwashimizu Hachimangu, above a series of inns which once housed pilgrims who stopped here to worship. Today, the inns are rotting slowly back into the damp hillsides. The final ascent is a series of moss-covered stone steps, worn down in the middle due to generations of footfalls. The shrine’s main hall has a unique construction, stacked up like one of those Heian period hats that nobles once wore, and its statuary looks more Asian than Japanese. The paint on the slatted box into which worshippers toss money has been chipped by a million coins. Trees dwarf the courtyard; the whole mountain-top is shaded by trees of sizes rarely seen in Japan anymore…

…It’s a surprisingly warm day for December. The sky is cloudless, but the wind stays in our faces for the entire six hours it takes us to reach Osaka. We continue southwest beside the Yodogawa, along one of those thick strips of green that flank any major river in Japan, most often seen from a train as it passes over long iron bridges. What is missed when seen from above is that these spaces have an entire culture of their own. Dark shapes of walkers move on the berm above us, silhouetted against the distant city skyline. Some people have cleverly improvised a tennis court, using as a net one of those metal barriers which prevents cars from entering. Others are playing baseball, having dug out bases and a pitcher’s mound with their cleats. Kids fly kites as spandex-clad adults race by on bikes. A homeless man has overloaded his bicycle, boxes stacked up a couple meters, and is scratching his head trying to figure a way to get on. A lone boy kicks a ball up the grassy berm, to have it roll back down to him. There are dog-walkers, nearly every one of their poor pampered pooches dressed better than most children. One spastic dog, unleashed, zig-zags like a squirrel. A construction site creates aural havoc. Middle-aged men are fishing at the end of simple piers made of thin boards slapped together. But the most constant sight of all are the hundreds of makeshift homes covered over with blue tarps. An entire city of homeless. Some dwellings are really impressive, with doors and windows and little gardens. One garden is massive, extending well down the river. A critic has spray-painted, “No gardens!” on one of the walls, which seems more the comment of a programmed and uninspired soul, protesting at the creative freedom of another. Do the occupants of these riverfront “homes” risk more physical attacks? One small cluster of families has about a dozen dogs, possibly as defense, possibly as food. Those dogs have no clothes whatsoever…

…We break for lunch, beside some wetlands hosting vast numbers of waterfowl, in spite of the filthy water. The call of one species sounds like the squeal of an excited prom queen. We sit on the concrete riverside, looking across the water at a scene from an Ozu film, of chimneys billowing smoke above identical houses, clothes blowing from backyard lines. We continue on into the wind, into near identical scenery. Years ago, Miki had biked this route, in a return trip from Kyoto to Osaka. She’d mentioned how dull it was. The well-heeled ancients bound for Kumano’s shrines rode palanquins to the foot of Otokoyama, then boarded boats downriver to what is now Tenmabashi. I had insisted we do it on foot, though biking may have been preferable after all. Fifteen kilometers over concrete and the feet begin to whine; over twenty, their complaints are deafening. We push on, both of us defiant and stubborn as always. After all, pilgrimage is meant to challenge, to pull us from our safe and comfortable spaces.

We pass under an old iron bridge shared by trains and pedestrians, arriving at a large stone marking the childhood home of the poet Buson. We follow the narrower Ogawa river south into the heart of the city. Planes bound for Itami extend their landing gear as they pass overhead. The spectacle of the sun setting through the clouds takes our minds off our feet somewhat, then lights begin to come on, neon shapes go-go dancing across the water’s surface. We arrive in full darkness at Tenmabashi, where warm coffee helps rebut the cold. On the hour-long train journey home, we revisit the day, like a film reel played at high speed in reverse.

Two weeks later we’re back here again, and quickly find the stone that marks the true start of the Kumano Kodo. We move south down streets lined with curry shops and old Taisho buildings now empty, still proudly bearing the names of businesses decades gone. We find a shrine dug into a tree that reaches up from asphalt, next to where Chikamatsu, one of Japan’s greatest dramatists, is buried. We continue on, past more buildings aging like ancient film stars, their beauty timeless but somehow anachronistic. Shitennoji temple is much bigger than expected. Before the temple’s Southern Gate, a long stone marks the way to Kumano, an indentation at one end carved out by centuries of prostrating foreheads. It is a hint that the pilgrimage may have pre-dated even this, Japan’s first Buddhist temple. I hear what I think is chanting — then realize that it is someone’s ringtone.

We cross the Yamato River. This is Sakai now, a sprawling cluster of suburbs. Unlike in Osaka, there are no trail markers here, and we begin to spend more time looking at the map and second-guessing ourselves than actually walking. The only real bright spots are the massive burial mounds scattered around these plastic homes. The granddaddy of all tumuli is just ahead, that of old Nintoku, dating from the early 5th century and larger in scale than the pyramids of Egypt. We traverse the park, watching hundreds of crows swirling around over the grounds, truly a Hitchcockian sight. It’s getting colder now; our enthusiasm decreasing with each wrong turn.

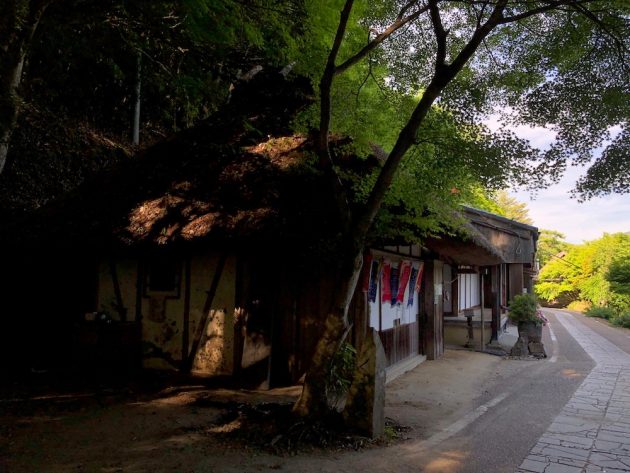

… We’d slept long and solid, needing rest to fight a long cold day, the most extreme yet. Snow teases us on and off. We are quiet most of the morning. I am soon tired of the suburbs, how they draw you in, then wear away at your sense of direction with their meandering uniformity. The morning leads us out of the bedroom towns, into villages linked by vegetable fields and small country train platforms. Many of the homes are still hanging on from late Edo, having served as lodgings along this Kumano Kōdō. Now and again we find markers commemorating generals who’d fallen in the siege of Osaka in the summer of 1615. Amazing to imagine tens of thousands of troops bivouacking here, marching on Osaka castle, way back near Tenmabashi and the start of this walk — how long ago? The day is wearing on, but we haven’t found a place to eat and escape the cold. At one shrine a few miko, shrine maidens, huddle in the dark. At another shrine, we see three girls in kimono, officially women now on this coming-of-age day. Centuries ago, a tremendous temple stood here, the center of life for a farm community where girls became women much earlier. The day goes on, and in my hunger and fatigue I notice little but the mountains getting heavy snow off to our left. Each step brings them closer.

We come to farm villages now, lanes narrower, residents more friendly. We climb to the Atago shrine atop a hill. Most of the village is up here, chanting along with purple-clad priests sitting before a handful of yamabushi who are preparing a goma fire at the center. Finding a few hand-painted signs showing a route not on our map, we follow them into the forest to a spot where a famous biwa player fell to his death, his instrument hanging from the tree out of reach. As legend recounts it, spray from the waterfall just behind supernaturally strummed the strings for years. We carefully cross this treacherous hillside, then climb to the pass. The last kilometer is along the narrow lane of an ancient mountain village. Here, at Yamanakadani, we stop. The Kumano Kōdō has changed names many times since we left Kyoto — Kyō Kaidō, Ōgura Kaidō, Kii Kaidō — but we have arrived at what feels like the spiritual source. We’ll leave the path for awhile, then pick it up again, to trace the perimeter of the overlapping mandalas that tantric Buddhists believe make up the Kii region. It’ll take a few weeks to traverse its trails, before finishing at the Shrines of Ise. I hope the gods favor us.

Osaka is separated by Wakayama by a narrow stream, the site of the final battle of the Boshin War, which brought an end to feudal Japan. We enter a village at the valley’s edge, houses spaced by rice fields, their stalks heavy and bending toward the dry cracked earth. We stop on the side of the road for snacks and tea, to the amusement of occasional farmers bicycling by. Across the fields is a large temple, where famed poet and beauty Ono no Komachi died 1100 years before while on her own Kumano pilgrimage.

…In Kainan is a small trail through the hills, shaded with bamboo and lined with stone Jizo statues of extreme age. Each has different features. This enchanted path leads us past a modest home stood surrounded by a large overgrown garden. This is the origin of the Suzuki family, and with 403,506 members, theirs is the most common surname in Japan. Just beyond is Fujishiro Shrine, hung with a humorous banner: “Welcome Suzuki-san!”…

…The hill rises and takes us away. Midway up is a flat indented rock like a calligraphy inkstone. The legend that accompanies it goes back to the 7th century. Atop the pass is a simple temple of dull wood, set against the brilliant blue sky. We have lunch here, followed by a dessert of mikan plucked from trees passed on the descent. This completely makes our day, eating fresh fruit as we walk along — tainted slightly by the sight of white chemical residue on their thick skins. This valley into which we are now dropping is surrounded by a Tuscan landscape of dry hills bearing colorful orchards. It’s hot going, the sun straight above and nearly no shade. Midway across the valley, we find what is touted as the first mikan tree in all of Japan, ancestor to all that wonderful sweet fruit to come.

We face a long ascent up concrete poured along the steep pitch. Near the crest of this high steep mountain, we find a group of very old men singing karaoke. They graciously give us water, but warn us that the taste might be off, as they had earlier sprayed for termites. In this heat, thirst beats prudence.

Down the other side, then we immediately face our second 400-meter climb of the day, into a forest landscape offering plentiful shade. We pluck a kiwi from one tree, but it is too sour to eat. The following descent is of the knee-killing variety all too common in this country, as if trails of this type were designed deliberately by orthopedic surgeons. We cross the valley quickly, over the Arida River and up into the next group of orchards. This is a lower hill than the last two, and a long gentle descent brings us finally to the town of Yuasa, whose main street looks centuries old. We pass through a cloud of incense as we make our way to the station, ending a six-hour crossing of some of the hardest passes on the Kōdō.

…Today, like yesterday, is a day spent getting somewhere, rather than being somewhere. We need to cross a 400-meter pass, supposedly the most difficult on the Kōdō. We don’t talk much for the first hour, except to curse Yuasa for having the most useless trail markers so far. Through the town center, there are plenty of them, but once away from businesses and shops, they disappear. I begin to see a certain pattern here. Signs erected by the municipalities are usually found in areas where money is likely to flow. Signs deeper in the hills or in the countryside are put up by citizen’s preservation groups, who have even rebuilt some of the protective Ōji shrines that mark the length of the Kōdō itself.

At five, we finally reach the park where we will camp, on a hillside, out of sight of the road and houses below. I love Japan for these places, with toilets, tables and shaded patches of grass. We drop our stuff and walk ten minutes over to Dōjōji Temple. The origination of the Anju story (later made into a famous Noh play), about the spurned lover who turns herself into a serpent and coils around the temple’s bell, burning to death the monk hiding beneath. It is well visited, and has the obligatory row of shops and restaurants, now mostly closed. One place is still open, the owner happy to share tales of local history. I am thrilled with my beer and curry — which consists of a mere three potatoes and a forlorn piece of beef. Near dark now, we set up camp back on our own hill, the row of windmills flickering on the range we’d climbed hours earlier, as if beckoning the late summer moon to rise red and full…

…We cross the Tonda River, marking the barrier of the Land of the Dead. And the monocultural sugi forest through which we climb is devoid of any life; no birdsong, no scampering insects. We pass through a narrow opening in the rock representing the womb. Officially within the Womb mandala now, and into this representation of Buddha in the natural world, we move up and up.

This trail is harder than I’d thought. There are certainly sections that would terrify anyone, the trail clinging to forested walls dropping off sheerly into cedars. At the top, an unfriendly group of middle-aged hikers are just finishing lunch, some of the women reapplying fresh make-up. Their guide tells us that they had taken an overnight ferry from Kyushu, would hike half the trail, then return by another night boat this evening. Express-lane pilgrimage. (In fact we ran into very few other walkers during the course of the pilgrimage, and unlike the figures in white gliding around Shikoku, none discernibly on pilgrimage).

Climbing again, we startle a large viper with bright yellow head pointing toward Gyuba Ōji, an impressive stone figure standing in perpetuity amidst a grove of tall cypress. On the same mound are diminutive figures of En no Gyoja, Jizo, and Fudo — a personal Buddhist greatest hits package, my three faves pow-wowing together. There is an unmistakable feeling of peace here, and the idea of having to leave is agony. Something indescribable is holding us in this place. After a long while, we finally get the feet in motion again.

We move up again, along a road that hangs high above the valley. I am well into the rhythm of the hike now, loving the scenery, the remote feel. Tsugizakura Shrine completes this sense of wonder, its stone steps rising between tree trunks centuries old. One elder had been standing here when the very first Kumano pilgrim strolled by over a millennium ago.

…Kumano Hongu Taisha is the center not only of the Kii region, but of the 3000 Kumano shrines throughout Japan. It is quiet here, having changed little since my 2005 visit, the same long steps, the same squat buildings rising from the gravel. One addition is the small stand selling kitschy character trinkets, including items of the Japan Football Association, which has adopted Kumano’s three-legged crow as mascot. (For the next three days, any time I see a crow, my eyes automatically check for that third leg.) Clapping my hands before the shrine, I feel happy, at peace. After years of trying to get to the Nakahechi, my feet have finally led me along this inner, mountainous passage of the Kōdō. I’ve finally completed the traverse of the Kumano Kōdō between Kyoto and Shingu…

…The Kii-ji and Nakahechi sections behind us, we return to Tanabe to begin the Ōhechi route that follows the Pacific shoreline. It is a monotonous morning walking out of town, following the busy Route 42 between massive box stores dwarfed by even more massive parking lots. Occasionally we are rewarded by being led down quieter roads parallel to the highway, or into farmland. One house bears the kanji for water, a talisman thought to protect the structure from fire. A watermark of a different type is cut into a stone slab, showing the reaches of a post-quake tsunami that had devastated this town in 1946. And the devastation continues. Due to the recently built mega-stores and their maze of access roads, this area no longer resembles our maps. Our confusion, the concrete, and the uninspired landscape do little for our spirits. The sacrifice of the old and traditional for the new and fleeting is beginning to wear us down. We need a rest.

…Ikora Chaya Cafe, just outside Tanabe, is a large open garden-like space filled with books and magazines on amazing topics. I grab a stack and sit out on the patio above a stream moving about as slowly as the day. One magazine’s pictures of Kumano cause me to fantasize about moving down here, spending my days doing research on the shrines and the mountains, my nights in conversation with the quirky residents. One such character is Tanaka-san, called A-chan while behind the bar. His taste in books and music are like my own. He takes us up to his home, a Therouvian bachelor pad amidst the plum groves. One room is empty but for a lone bed. Another room, very dark, has two chairs, two towering speakers, and stacks of LPs climbing the walls. I’d seen music rooms like this in ads, but never in anyone’s home. Upstairs is a loft, with a couple old organs and baskets full of guitars. Throughout the house are unbelievable antiques and books. In my greatest loner moments, this is the house of my dreams.

Back at the cafe, A-chan and I chat awhile, until I take one of the shakuhachi off the wall and began to blow. A-chan joins in on fue, our notes harmonizing much like our conversation had, and like the way he blends the spiritual richness around him with his simple but rich lifestyle.

This day off came at a perfect time. I was the most tired I’d been in the nine days since we’d set out, and the concrete landscape has gotten so bleak that we decide to cut the final six day Ise-ji section off our trip entirely. We’ll finish in Shingu, where the Ōhechi ends. The road to Ise can wait.

…The trail is narrow and overgrown, looking more like jungle as it hugs the hillside 20 feet above the Hikigawa. When it drops again, we walk to the water’s edge, into its clean smoothness. People used to cross here by walking across planks laid over boats tied end to end. Today a single boat is moored on the opposite bank, rides available to those who telephone the owner.

After a quick calf-burning ascent to the pass, we rest awhile, then drop down an incredibly steep pitch, my pack shoving me forward all the way down. Further down is an unusual shrine dedicated to the god of the Earth. Although there is a stone base, nothing is placed upon it, signifying that the object of worship is everything beyond: the trees, the rocks, the hills…

We walk down a stream tracing a long valley filled with shorn rice fields and the odd farm. Plum groves, barrels tied to trunks of maples in order to collect the sap. Just after the noon chimes, we turn left at the town candy shop and arrive at Susami station. The lone employee sits in his office, brushing his teeth at his desk. It’s a pretty weird place, one half converted into a museum dedicated to squid. Dozens of photos on the walls, and as much kitschy squid tat as you could fill your car with. A large tank nearby doesn’t actually hold any squid, just a lobster, two small sharks, and a particularly toothy eel whose mouth is perpetually open as if in disbelief that it is even in here.

The final big climb of the Kōdō is lower than the previous two (388m), but it is short and steep. At the top, the trail is a squared-off path that crumbles away on both sides. The twisted and gnarled maze of roots along the trail betray earth packed down by a millennium of passing pilgrims’ feet.

The steep descent drops us amidst a few houses and a small train platform, Mirozu. We collapse onto a bench and quickly down a cold drink from a machine. The platform is small and remote, a mere concrete shell with two long benches running the length of both sides, wide enough for sleeping. The problem is that we have nearly no food. After a quick shower from the hose out back, I tuck into my dinner of beef jerky and chocolate cupcake, washed down with the remains of the tea in the thermos. We read and write while waiting for the final 10:22 train, before rolling out our sleeping bags, hoping that the mosquitoes give some respite…

…The route takes on a predictable pattern, weaving on and off Rte 42, and onto the smaller roads paralleling it, which drop up down into fishing villages, or lead into the farm settlements of the hills. There are also quite a few coves, and arriving at these, we sit awhile, staring out at the waves. From Rte 42, it is easy to see portions of the real Kōdō, hidden in the overgrowth of forest. Will they eventually be restored as part of the mapped system?

…Where the trail ends, we have lunch beside a quiet river. We circle around a pair of lakes, then move up the final pass of the day and — for us — the Ōhechi. Each pass we’ve crossed over the last five days has been a little lower than the last, making this one a mere baby, comparatively. At its top is a Jizo that supposedly has healing powers: the high tech A/V system beside it tells us so.

Dropping next into Kii Katsuura, we move through town past the old sake brewing factory toward Nachi station. This section is a mess, far too many roads built with tourist money, in the hopes of luring even more. What I see before me completely justifies the internal voice I heard back in 2003 when I first learned that Kumano got UNESCO World Heritage status: “Before they build it, you should go.” Miki notices posters put up by a resident’s group opposed to a proposed nuclear power plant.

We pay a quick visit to Funarakuji temple, which houses a marvelous collection of statues and faded paintings, all shaded by majestic trees 800 years old. Beside the temple building is a model of an old sealed boat. Upon reaching the age of 60, certain monks would be sealed inside and set adrift, faithful that they’d reach the Pure Land. Of the twenty who attempted it, only a single monk returned.

…We walk through Shingu to Kuragami Jinja, not one of the three Kumano Grand Shrines, but certainly the most shamanistic. The rocks leading up are jagged and wild, befitting a place where yamabushi train. A young, thin woman appears from out of the forest, then turns in prayer toward the mountaintop. Something about her resonates with something in me, some power she emits. Miki and I walk over uneven steps toward the source. In front of a large tree is a stone the size and shape of a Jizo. Thought lacking any distinct features, it has a collection of small white stones around its base. When we come down later, an old woman is standing before it deep in prayer. What secrets does it contain?

The shrine at the top is equally powerful, built into an immense boulder. Behind this is a gap — the typical passage to rebirth found in Shugendo. We descend again and walk over to Hayatama Jinja, discussing whether this has been a spiritual experience for us. We both agree it hasn’t. Sure, we’ve suffered some and learned a handful of things about ourselves, but overall, it has just felt like an especially long hike.

This feeling changes once we get to this, the third of the Grand Shrines, and that feeling of spirit comes on in a sudden rush. The trees, the quiet dignified buildings, the quality of light, all contribute to a great feeling of peace, of not wanting to leave its sacred precinct. I’d been here twice before; hadn’t felt it then. But today, this place, a major source of Japanese folk spirituality, has drawn me in. We bow in thanks before all the gods, and with that, our Kumano pilgrimage is done.

A more complete version of these travels journals can be found here.

Based in Kyoto, Edward J. Taylor’s work has appeared in The Japan Times, Singapore Straits Times, Kyoto Journal, Skyward:JAL’s Inflight Magazine, Resurgence, Outdoor Japan, Kansai Time Out, and Elephant Journal, as well as in various print and online publications. Graduate of the University of Arizona’s renowned Creative Writing program, he won the top prize in the Kyoto International Cultural Association Essay Contest, and now serves as a Contributing Editor at Kyoto Journal. Edward is the co-editor of the Deep Kyoto Walks anthology, and is currently at work on a series of books about walking Japan’s ancient highways.

Photos by Edward J. Taylor.

Illustration by Jérôme Boulbès. His animation work can be found at: vimeo.com/jeromeboulbes