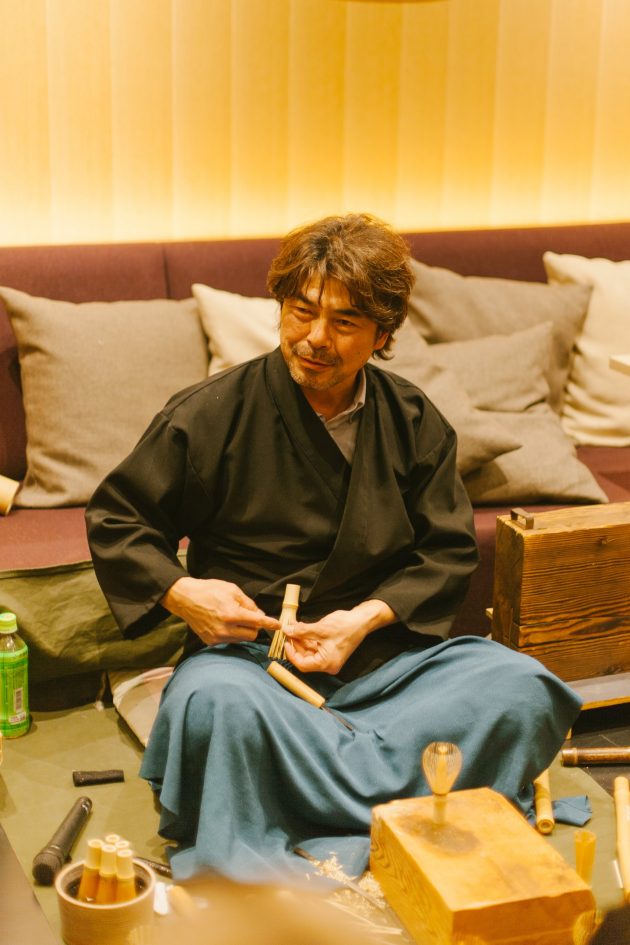

One chilly Saturday afternoon in February several members of the KJ team ventured out to Nara for a workshop with Tanimura Tango-sensei, a master craftsmen of chasen: tea whisks used in the Japanese tea ceremony. We had previously featured Tanimura-sensei in issue KJ89: Craft Ecologies, in an article by Ai Kanazawa of Entoten. The workshop was attended by a small group at NARANICLE, a relatively new event, café and retail space on Sanjo Street.

Only 18 households in the whole country are engaged in making chasen in Japan today: in Takayama-cho, Nara Prefecture. Chasen-making, like other crafts in Japan, was a skill passed down exclusively from father to son (一子相伝), but making this an open secret has become a matter of necessity. Namely, when faced with competition from inferior, mass-produced items from China, makers need to be able to build a case for laypeople and students of tea alike that nothing really compares to a handmade chasen.

Sensei explained that the chasen occupies an unusual and perhaps underrated role in the tea ceremony simply because it is not quite as prized as the other utensils (or chadōgu 茶道具): chasen are not given typically poetic names. Related to this point, Sensei felt it necessary to draw our attention to the fact the word “chasen” is written with two different kanji: 茶筅 and 茶筌, whereby the former really denotes it as a “tool” and the latter as a work of bamboo “art.” In any case, this did not quell our curiosity as to how these impossibly fine objects are made. And yes: they are indeed made from a single piece of bamboo.

Sensei gave us the low-down on the types of bamboo one might see being used in chasen — at least those made for the Urasenke, Omotesenke and Mushakoji-senke schools of tea (there are quite a few others in existence today, but they are relatively small). The most desirable though is not so much a particular species of bamboo, but that recycled from the ceilings of old farmhouses: exposed to soot from open-hearth fires, they develop a wonderful patina. This type is increasingly difficult to find, however, and so shokunin are attempting to find ways to replicate this effect artificially—and much more quickly!

In terms of the ideal form, Sensei explained his tendency to work with slimmer lengths of bamboo, and creating a much gentler curvature to the whisk prongs than some of his counterparts, which taper off at more of a 90-degree angle. This can be better explained visually, i.e. by watching a tea practitioner whisk matcha powder in a chawan tea bowl, but clearly it makes sense to create as much surface area for the whisk to cover without making contact with the sides of the bowl, which can then wear it down over time. It was surprising to learn that the original whisk used in China (though it lives on in Japan, such method of tea preparation does not exist there anymore) was much more crude: something like what you see in the very early stages of chasen making which looks rather stumpy and inflexible.

Though workshop was much more about witnessing Sensei’s mastery we still were able to try our hand at completing the final touches to our own chasen, which involved weaving coloured thread around the body of the whisk. One poorly coordinated participant had to ask her friends to do it for her…(that may have been me).

It was a fantastic privilege to see Tanimura-sensei at work, and I would urge visitors to Nara to take the time to visit his workshop up in Ikoma. Thanks to Minechika Endo who took these lovely photos and to Mizuho Toyoshima for sharing her notes from the event.