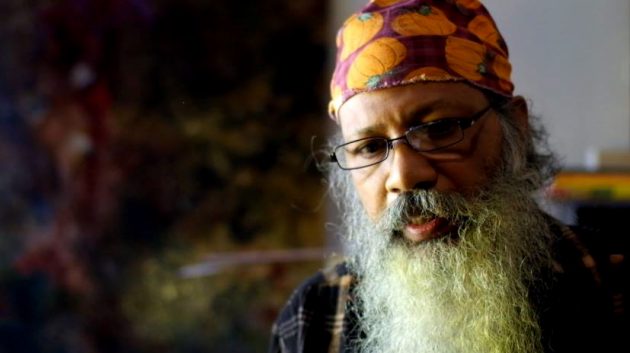

The New York based artist Venantius J. Pinto describes himself as an artistic labourer and his drawing as an organic process. His incredible illustrations, situated at the very intersection of religion, sexuality, and consciousness, have enriched several of the fiction and poetry pieces in Kyoto Journal over the last few years.

Who is the man behind the brush?

I am of Indian descent, born in Bombay of Goan parentage, and grateful that my upbringing was among different religiosities. I draw to understand my thoughts, and those of others to include the stirrings, the evocations, and lived aesthetic spaces that certain people seem to completely inhabit. My drawing surfaces have ranged from painting bodies to paper, and mica.

How did your artistic journey begin?

Perhaps, the search for possibilities in phenomena that passed across and within my senses led me to fully embrace this role. I come from humble upbringing and simply did not have the courage to pursue art studies as in painting, hence, my education is in design: advertising, design for social issues, communications design, computer graphics, applied disciplines… This was, or so I believed, to be able to survive and provide. However, time and place colluded to abate my anxieties. Now as an artistic labourer, I enter spaces through my drawings and in doing so to bring out a nature that otherwise I would not be privy to. “Layering” is a metaphor for encapsulating fragments and wholes that convey power, compassion, and the memory of time & culture.

I heard that you are trained in shuji calligraphy. How would you say that shuji calligraphy influences your artwork, or your way of thinking as an artist?

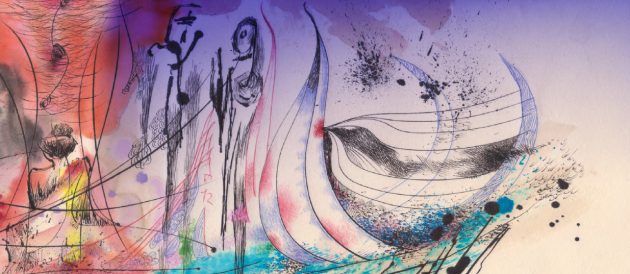

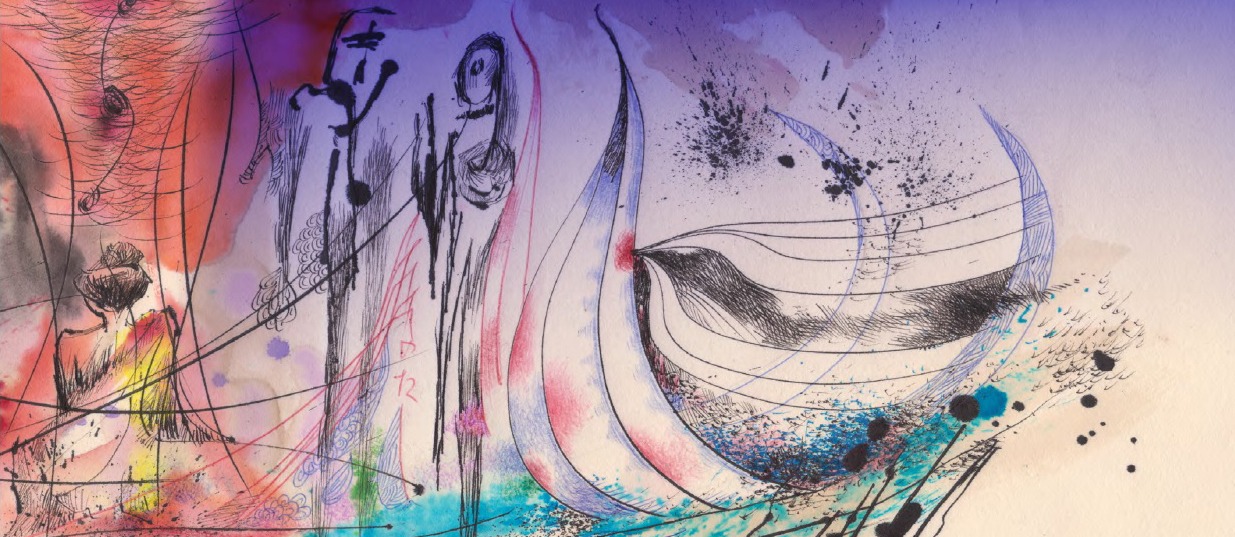

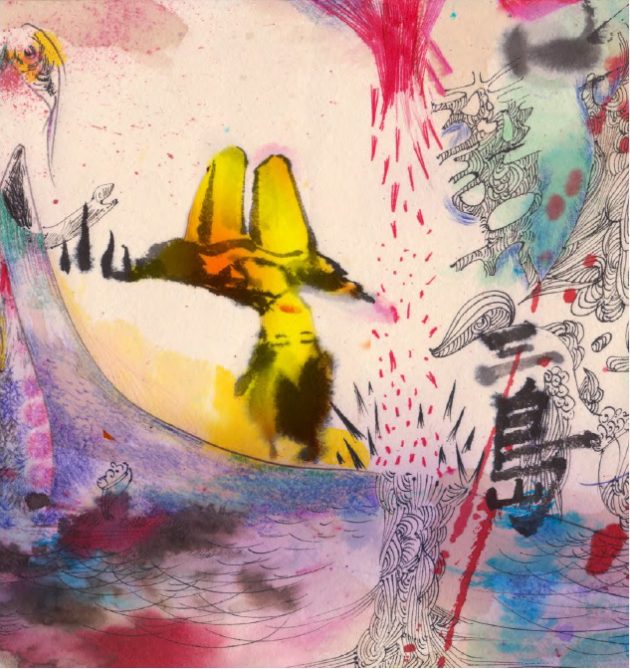

The desire to study Shuji came about from wishing to will the mind’s eye through refractions on things experienced. It was a revelation to learn that Madame Wei (Wei Shou 卫铄) of the Jin dynasty upon seeing part of a cliff fall off, decided to encapsulate it in her “dot stroke.” In particular, Kana and Rinshō have afforded many insights, which I have been resourceful in extrapolating and embracing in my way of seeing phenomena, whether observed or read. Briefly, I have imbued various manners of fluidity’s from the former, and the stroke qualities of various exponents from the latter. Between them is a trove of possibilities for any calligrapher, leave alone for an artist — through line, pressure, flicks, blotting, traces, tonalities in ink; and scale — all of which I extrapolate and convey in my art. So, the shaping of form and seeing is an osmosis, via the practice of both, as also from other forms of in Shodō, including the sister art Tenkoku which bears upon the quality of movement and the manner of inflecting it in stone. For Tenkoku, I indeed use the chisel essentially as a steel brush, which reverberates within my being. I often jab the brush, use it as a rope, and so forth. Looking assiduously at the Sanpitsu, the Sanseki, as also other greats over time incorporating movements refined centuries ago and down lineages into my artistic reality.

How would you describe your work?

My artistic labour is reflective, it’s about sensing intent, and very true particularly with poetry. So, one aspect is analytical, and the other is to flesh out certain nuances that may only be alluded to. A visual clairvoyance of sorts! I bring all my experience to bear: seeking detail in detail, partitioning space akin to various forms of miniatures, creating ruptures in the narrative but then bridging continuing at another point in the composition, use of symbolism, visual congruency with fantastic realism, using colour as discrete units of energy, mixing stylistic elements, and creating a visual sound if you will.

How would you describe your creative evolution as an artist?

There have been many depressions, and a few resurgences over the years, which have shown me how a path gets shaped into one’s own! When I receive text, I always think why me. The response helps me see the text through a clean lens. Then I proceed to see it from two or more sets of eyes, finally agreeing on one viewpoint, while still being open to incorporating guests to shape the whole. Essentially working with fragments right from accepting a viewpoint towards coalescing into a whole. But, it’s about being receptive to receiving, and with gratitude. At this point in time, I am whittling away at the obvious, but some pieces will continue to be laden with complexity. I cannot simply drop honed skills, and sensibilities innate to me, and which cooperate in the way I see these visual worlds. Carl Sagan put it beautifully; “Imagination will often carry us to worlds that never were. But without it we go nowhere.” Imagine! So it’s about seizing each moment and respecting the text. No shortcuts, but for simplicity when called for, yes! Or perhaps somebody else should be working on that piece, as opposed to me. I am open to seeing works by those who have gone ahead. I am more secure and not awed, but remain respectful.

Where do you find your inspiration?

Observation and respect are what my senses glean. My inspiration stems from being accepting and learning to varying degrees from a plethora of the arts, whether fashion, music such as Kyōgen, inflections in Enka, pigments, butoh, poetry, kotowaza, embroideries, including other proverbs, the esoteric, etc. In the practice of Rinshō, the copying or even concentrated viewing the calligraphies of Wang Xizhi (王羲之) (Wang Xizhi (王羲之) is known as Ogishi in Japanese), Kūkai (空 海), Ono no Michikaze (小野道風), the Hokugi (北魏), and others reflects on my brush movement in illustration. One sees space differently from before. Early on I embraced a vigil, seeking at the intersection of religion, sexuality, and consciousness, which brought me a lot of insights. As I encountered in Jeremiah 6:16 Stand at the crossroads and look; ask for the ancient paths, ask where the good way is, and walk in it, and you will find rest for your souls. A lot of what I do it could be said comes from old wineskins, and I am grateful that I can make analogies and spin on a dime when need be.

How did you get involved with Kyoto Journal (KJ)?

During my early years in NY, I would buy a few copies of KJ at Hudson News (they would vanish quickly); and appreciated their content, which to me was genuine and of a whole other world. Many years later, Carey Biron who was with HIMAL Southasian, Kathmandu mentioned he’d introduce my work me to KJ. But then he moved on; still, the possibility of engaging with KJ stayed with me. I always wished to make contact with KJ, but he was the catalyst. Now I feel more comfortable to put myself out there. Anyway, I believe it was Ken Rodgers who responded favorably to my reaching out. And then, John Einarsen contacted me regarding a complex poem by Shiraishi Kazuko! Then there was the next, and it has continued.

Which piece of work for KJ are you most proud of, and why?

A trifle hard to say, but I lean towards my first for Shiraishi Kazuko. It brought various structural elements into play, including radical feminism, a slew of references, my understanding of the various strands in Vernal Planet, settling on one set of eyes, the decision to meld sumi with humble media like the ballpoint, the idea to incorporate Mishima’s name in calligraphy, consciously blurring kaze. Besides, it was my first and remains my only illustration on Echizen kozo. Finally, the dimensions at 56.5″ x 8.5″ in width, and the narrative coming together on that expanse. It was sketched out pretty tightly; the final was a blur in execution.

Why do you think that your artwork fits so well with the spirit and content of KJ?

For me, KJ is a nebula of various senses. It shines and has provided a lintel to my sensibility in the most egalitarian manner. More than simply the art, its the acceptance of the editorial/design mavens; who permit me playing the text in various narrative structure: via unusual space dynamics and indeed colour, on a couple occasions employing multiple techniques, color as discrete units of energy, working in a gamut of styles, and developing newer ones, certainly for the poems — although I could stay with one! It’s about going through the fire, much like in school, when I would hurtle through the ring of fire. To me, KJ is about a quiet exuberance, an assured temperance, and the door being left open for me. If anything, one never knows where the end is, but with Einarsen and the journal, I have realized strands of my potential. The acceptance cannot be easily expressed.

Lisa Nilsson, hailing from Sweden, recently joined Kyoto Journal as a volunteer and is currently working on a series of interviews with KJ team members.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013