“Museums are servants of memory,” said Bonita Bennet, Director of District Six Museum in Cape Town, during a plenary session at the International Council of Museums’ (ICOM) 2019 General Conference in Kyoto. “But the power they wield also makes them historical custodians of colonialism, and play a critical role in rituals of remembrance.”

This was the tension at the heart of two simultaneous sessions on the second day of ICOM Kyoto, which discussed how colonization and war crimes are represented in museums. While addressing distinct and systemic issues, they aimed to highlight the need for museums to actively construct more holistic narratives through the increased representation of those who lived under imperialism. This was a particularly poignant topic for the Kyoto-based conference, given Japan’s imperialist history and its museums’ tendencies to exclude the voices of those perspectives from its former colonial territories.

A joint session between Memorial Museums in Remembrance of the Victims of Public Crimes (ICMEMO) and the Federation of International Human Rights Museums (FIHRM), titled “How Museums Say the Unfathomable: Voices from Former Colonial Territories of Imperial Japan” included two speakers who addressed the importance of testimony in museums in order to highlight the perspectives of Okinawan and Taiwan civilians who lived under Japanese imperial rule.

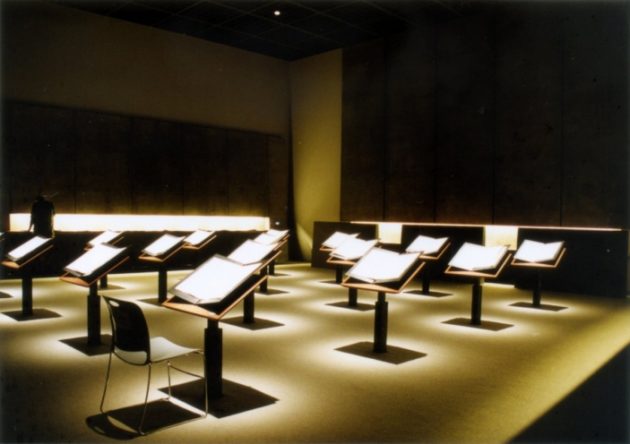

Kaori Akiyama, a Research Fellow with the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, presented case studies on the use of testimony by the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum and the Himeyuri Peace Museum to detail civilian experiences and perspectives during the Battle of Okinawa in WWII. These exhibits included books detailing first-hand civilian experiences, portraits, and replications of the horrific conditions Okinawans endured. Akiyama stressed the importance of including oral histories in such exhibits, especially in cases like Okinawa where physical materials are virtually nonexistent as a result of extensive fires and destruction.

“We have to rely on testimony,” Akiyama said. “How it is evaluated is a debate, but museums can present many testimonies to let the public decide.” She further suggested that the absence of physical evidence has been a part of why Japanese museums have justified the exclusion of certain narratives about the country’s imperialist past, resulting in the perpetuation of mono-national narratives in exhibits.

Similarly, Lin Chia-Yi, a research assistant for the Public Service Division of the National Museum of Taiwan History, analyzed the use of a witness study group to reflect on Japanese rule in Taiwan from 1895-1945 in her presentation, “Who is Speaking: The Unfathomable Memory from Taiwanese During WWII”. A group of ten participants shared the memories of their reactions to the news that imperial rule had ended, illustrating a range of complex emotions and perspectives that had been previously ignored by institutions.

These examples evidenced the acute relationships entwined within the politics of memory and the political systems that determine how memory is recorded, manufactured, and disseminated. The structures and constructed narratives inherent in this are intrinsically linked to the educational role that museums have played and endeavor to fulfill in society, a point which is touched on in ICOM’s Code of Ethics for Museums. For this reason, the democratization of lost memories, along with the decolonization of cultural heritage, are pertinent issues that speak to the larger focus of this year’s ICOM, which examined the definition, mission, and ambitions of museums moving forward.

“How can you tell the story of what has gone wrong?” asked Beate Reifenscheid of ICOM Germany in a session on Decolonisation and Restitution. “We must think about the moral impact of telling and not telling these stories.”

Indeed, recognizing the issue of collective amnesia—the purposeful repression of narratives and voices—is perhaps equally critical in the process of reimagining the role of museums in contemporary society and the position they occupy in shared experience. Many ICOM participants seemed to agree with this sentiment. However, just as with the Conference’s proposed definition for museums, the challenge will be translating theory into practice on a wider scale.

This sentiment was directly addressed in a point made by George Okello Abungo, a Cambridge-trained archaeologist and former director-general of the National Museums of Kenya: “The majority of museums still feign colonial amnesia, hoping for history to heal the injuries and injustices and for time to erase the memories of the past,” he said in a discussion of the proposed definition. “I have been collected, I have been studied, I have been researched. Can my voice now be included in this new definition?”

KJ is posting a series of articles on ICOM Kyoto 2019 to provide more context on the diverse and important topics discussed at the conference. We invite you to continue reading with The International Museum Community Arrives in Kyoto by Ty Billman.

Codi is a freelance journalist, communications specialist, and researcher. Her reporting projects have taken her across the world, most recently to Kyoto where she currently lives. Her personal work focuses on how emerging technologies change human relationships and the impact of tech platforms on journalism, civic discourse, and democracy. http://www.codihauka.com/