Philosopher and critic Tsurumi Shunsuke was born in 1922 in Tokyo. He attended school in the US from age 15 to 19, graduating young from Harvard University. After World War II, Tsurumi started the highly-respected philosophy magazine Shiso no Kagaku (Science of Thought), serving for half a century as its editor and publisher. From the 1950s to the 1970s, he was an outspoken anti-war activist. In 1960, he resigned from his post as a professor at Tokyo Institute of Technology, in protest against the Japan-US Military Alliance. Tsurumi’s most famous books are Recantation: A Cooperative Research Project, Studies of Marginal Art, and The Legend of Amenouzume, among others.

The year 2005 marked the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II, inviting reflection on dramatic recent changes in Japan’s social and political landscape. Currently, one of the most heated topics in politics is the possible revision of Article 9 of Japan’s Constitution, which calls for the renunciation of war and the demilitarization of Japan’s armed forces. Tsurumi Shunsuke serves on the board of The Article 9 Association, Kyujo no Kai, and has avidly watched the social and political changes occurring in post-war Japan for more than five decades. During this time, Mr. Tsurumi has been an active and sometimes controversial figure, urging Japanese intellectuals to take responsibility for the war, organizing pacifist groups such as Koenaki Koe no Kai and The Citizen’s League for Peace in Vietnam (Beheiren), as well as authoring many books.

OKETANI: At the age of 15, you went to America. One year later, in 1938, you attended Harvard University. What was this experience like for you?

TSURUMI: Well, let me talk a bit about my family life before that. When I was quite little, my mother perpetually punished me. Although I have two sisters and a brother, I was the only one she focused her attention on. She always scolded me, saying, “You’re a bad boy.” Deep down inside, I realized that she loved me the most, and that was why she was so strict, but when I was small, I didn’t know how to rebel against her, so I tried to endure the punishment. But when I became a teenager, I started rebelling by attempting suicide. I was actually kicked out of three different schools. So, my father sent me to America. The following year, I entered the philosophy department at Harvard University and took courses at the Harvard Divinity School, which was a Unitarian school. The school had a deep connection to Emerson and Thoreau, the Transcendentalists. Emerson, as you know, was greatly influenced by Indian philosophy, and wrote many poems about it, including “Brahma.” Hinduism also had an impact on Thoreau. Both were greatly influenced by the Asian concept of the Divine. I studied systematic theology, which included the concept of atheism. In systematic theology, it didn’t matter whether you believed in the existence of God or not. In Hinduism and Taoism, the concept of God is different from that of Christianity, which has only one God. Picture a mandala with many buddhas and bodhisattvas — a mandala and the universe it represents is all-inclusive — it does not expel a buddha or bodhisattva for “heresy.” This is the Unitarian belief my ideals were rooted in.

How does this belief affect your actions today?

In the activities I’ve organized, such as the magazine Shiso no Kagaku (Science of Thought), Group of Voiceless Voices, and Beheiren, there is one consistent feature, and that is that no members have ever been expelled. Expulsion is an extremely humiliating treatment, as we saw in the Soviet Union with the Comintern, which expelled its members, and in many Marxist countries and parties in the 20th century. Marxism has its roots in Christianity, and in the history of Christianity we find expulsion for alleged heresy, such as the expulsion of Protestants. Now, even in the post-Marxist 21st century, governments still use the concept “God” to control those with different viewpoints, branding those views as “wrong” — as if the position of those in power were absolute justice. I have never believed in such a thing as absolute justice. There must be tolerance for different points of view. Regarding our activities, I’ve never made any restrictions on people being able to use our group’s name to organize their own group. In Japan, historically, people need to belong to some political party, group, or labor union to take part in a demonstration. I took issue with that. So, in 1960 when the movement against the Japan-US Military Alliance was in full force, we organized the Koenaki Koe no Kai. The direct reason was because a woman member of Shiso no Kagaku said, “I’ve never taken part in a demonstration.” So, we organized a group that anyone could join, and whose name could be used freely. And Beheiren and Kujono-kai inherited that philosophy. Nowadays, there are three thousand groups in Japan with Kyujo no Kai as their name. I think the way I do because of my education in America. But these days, I’m up against 280 million Americans plus 100 million Japanese, since America supports Japan’s war aims.

You were arrested in America in 1941. What were you arrested for?

In 1928, when I was five years old, the newspapers issued an “extra” on the death of Chang Tso-lin, who was killed by a bomb. [Editor’s note: Chinese general Chang, leader of a Manchurian militia unit, had assisted the Japanese in the Japan-Russia War, 1904-5]. My father and grandfather were politicians, and there were many houseboys in employ at our home. They told me that the Japanese had killed him. At that time, I didn’t have any idea who “the Japanese” were. I thought “the Japanese” must be a terrible, scary people. This experience led me to believe that the Japanese were at the root of this terrible incident. However, in Japan, almost no one believed that the Japanese killed Chang Tso-lin. Then, in 1938, I went to America. Almost everyone I met in intellectual circles there criticized the Japanese invasion of China. When they criticized Japan, I didn’t have any feelings of discomfort, because I grew up with the concept that the Japanese were bad people. And I thought that I was a bad boy among the bad Japanese.

In the fall of 1941, I received a letter from the Japanese Embassy in Washington telling me to go back to Japan on the next ship out. So, I asked my sponsor, Professor Arthur Meier Schlesinger (the father of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr.) what to do. I met with Professor Schlesinger and Tsuru Shigeto (former president of Hitotsubashi University), who was teaching at Harvard at the time. Professors Schlesinger and Tsuru both had the opinion that Japan would not start a war. Mr. Schlesinger thought that the Japanese leaders, who had made great progress since 1853, would not make such a poor decision to ruin their country. But I had a different opinion—that Japan would start the war. I wasn’t smarter than they were. I just felt that way because I grew up in a family of Japanese politicians, where many politicians visited and called often on the phone, so I couldn’t help but overhear their conversations. They are self-promoting people, just like the Japanese proverb says: “The weaker the dog, the louder the bark.”

In 1905, the Japanese sat on their laurels after the Japan-Russia War, believing Japan had won the war. But that was an illusion. The truth is that Japanese succeeded in ending the war with a less favorable condition than they anticipated. Many senior statesmen and generals in the Meiji government had the ability to judge the situation objectively, and they had the courage to end the war. If Japan had continued at war, it would have been defeated by Russia, like Napoleon and Hitler. These men could see the future objectively, but after the Japan-Russia War, the Japanese believed themselves to be one of the top five nations in the world. Meiji-era politicians perpetuated this illusion in order to increase national prestige. But Taisho- and Showa-era politicians were trapped by this illusion, and they escalated the attempt to make themselves and others believe that Japan had become one of the top three nations worldwide, and finally one of the top two nations — Japan and America. And by then, the Japanese had the illusion that they could win a war against America.

Anyway, at that time, I sent the Japanese Embassy a letter saying that I would not return to Japan. Then, the Pacific War broke out. Soon after that, the FBI came to investigate me and to ask which side I would support— Japan or America. I answered, “I don’t think Japan is right because it has a military alliance with the Nazis. I would support neither Japan nor America. I don’t support any government, because I am an anarchist.” At that time, I didn’t know that “anarchist” essentially meant “terrorist” in America. The FBI misunderstood me, and I was quickly arrested and sent to a detention center in East Boston. The majority of the prisoners there were German, followed by Italians. There was only one Japanese; me. But I had a good experience there. The American government treated me in a perfectly constitutional way. They gave me legal hearings and didn’t torture me. I felt that I had touched the very foundation of American democracy. This experience established the basis of my trust in America, and that didn’t change — even during wartime.

I thought I would be released quickly, because my case was a “false arrest.” But when the authorities asked me if I would go back to Japan or stay in the detention center until the end of the war, I wondered whether I should just stay there and wait out the end of the war safely. Actually, life at the detention center was not that bad, because the food was very good. But I couldn’t imagine that I would be on the winner’s side at the end of the war. And, on a personal level, in some way my relationship with my fellow Japanese constrained me. In spite of our difference in views, it was almost a sado-masochistic relationship, and because I was a mental masochist, I answered, “I’ll go back to Japan,” even though I didn’t believe that Japan was right, or that Japan would win the war by any stretch.

How did you feel upon coming back to Japan?

I felt as if I had come back to the enemy. Actually, I didn’t think I would pass the conscription exam or be recruited, because I had consumption and the symptoms of caries had already surfaced. But the recruiters seemed to feel that someone who had been sent by his parents to America to study should be re-educated into a “good Japanese” through military service. So, I passed the test. Then, I applied for a position as a German translator in the navy, because I thought that the navy recruits would be treated more reasonably than the army. But I was wrong. They treated the soldiers so cruelly; soldiers were beaten everyday. Then, I was sent to Java, where there was a submarine that was being sent to Germany, but it couldn’t break through the American blockade, so we stayed in Java. After the actual appearance of an American military ship that had been reportedly sunk by a Japanese attack, the navy could no longer trust the news announcements issued by the Imperial Japanese headquarters, so I was ordered to make a newspaper like the one the enemies read based on military information from American and British radio news reports from the New Delhi Broadcast Company, the BBC, and the UPAP. I listened to the radio news during the night and put together the newspaper the next morning. My job was to make the newspaper, but I was always thinking of what I should do in battle. I didn’t want to kill anyone. So, I decided to commit suicide before I was faced with having to kill someone. Opium was available on the Japanese military bases, as the Japanese army was engaged in the drug trade. Some smoked opium with cigarettes to get high. I stole a little at a time, and hid it in the pocket of my military jacket. And I decided to commit suicide by overdosing on opium if faced with having to shoot the enemy.

conscription exam or be recruited, because I had consumption and the symptoms of caries had already surfaced. But the recruiters seemed to feel that someone who had been sent by his parents to America to study should be re-educated into a “good Japanese” through military service. So, I passed the test. Then, I applied for a position as a German translator in the navy, because I thought that the navy recruits would be treated more reasonably than the army. But I was wrong. They treated the soldiers so cruelly; soldiers were beaten everyday. Then, I was sent to Java, where there was a submarine that was being sent to Germany, but it couldn’t break through the American blockade, so we stayed in Java. After the actual appearance of an American military ship that had been reportedly sunk by a Japanese attack, the navy could no longer trust the news announcements issued by the Imperial Japanese headquarters, so I was ordered to make a newspaper like the one the enemies read based on military information from American and British radio news reports from the New Delhi Broadcast Company, the BBC, and the UPAP. I listened to the radio news during the night and put together the newspaper the next morning. My job was to make the newspaper, but I was always thinking of what I should do in battle. I didn’t want to kill anyone. So, I decided to commit suicide before I was faced with having to kill someone. Opium was available on the Japanese military bases, as the Japanese army was engaged in the drug trade. Some smoked opium with cigarettes to get high. I stole a little at a time, and hid it in the pocket of my military jacket. And I decided to commit suicide by overdosing on opium if faced with having to shoot the enemy.

What happened then?

Well, there’s an incident that I think is important to talk about. One day, the unit to which I belonged captured an Australian commercial ship. There was an African from Goa (then a Portuguese colony) on the ship, and he was so sick that the head of our unit decided to execute him, because allegedly there was not enough medicine even to treat the Japanese soldiers, let alone for this prisoner. The order to kill the man was given to a civilian employee of the navy (just like me) in the room next to mine. He was half-British, half-Japanese, and could speak English, so that’s why they chose him. He suffered terribly from this predicament. He told me that when he brought the prisoner to the place of execution, the man thought he was being taken to a hospital, but there were soldiers waiting for him, already digging a hole. He gave the man poison, but it took a very long time for the man to die, so he had to shoot him in the end. It was merely by chance that this order had not been given to me. Since I could speak English too, it could have easily been me who had to kill him. I thought about this incident for years after the war. If I had been ordered to kill the prisoner, there is a possibility I would have submitted to the order, because I was too much of a coward to resist. And what came to me was that if I were put in that horrible position, I wanted to be a person who could say without hesitation, “Yes, I killed, and I admit that killing another person is wrong.”

You urged Japanese war responsibility through your book Recantation: A Cooperative Research Project, but you also spoke of the injustice of war trials. Can you explain your view?

I have insisted that war trials are unjust because they are judged by the victors, in an absolute sense. If war trials are held, the victors should be judged alongside the defeated. In terms of WWII, the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki should have been judged as well. Even on the American military side, some people like Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy were against the use of the atomic bomb on Japan. In 1945, the American government knew that the Pacific warships were completely destroyed and that Japan had no ability to produce weapons, because most of its factories had been destroyed in the air raids. There was no necessity to use nuclear weapons. But Truman disregarded Leahy’s opinion. He wanted to drop the atomic bomb to persuade the House and the Senate to support the huge cost of nuclear arms development. Over the last sixty years, the American government has perpetuated erroneous information on this issue.

What have we learned from this?

It’s important that those who have weapons exercise strong self-control. This is a lesson I learned in jail in 1942, in America. One day, there was a fight between two young prisoners. Among the prisoners were a professional wrestler and a boxer, but they didn’t jump into the fight to try and break it up. They only watched it, because they knew that their bare hands were weapons which could easily kill someone. Even if they had tried to break up the fight, they might have killed the men while trying to separate them. So they didn’t get involved.

I’m eighty-three years old, but to me, this is still the highest ethical standard. Those who have weapons should behave accordingly, and if they make the decision to use those weapons, that decision should be made very, very carefully. In the same way, the leaders of countries who possess nuclear weapons should understand seriously that they have very destructive weapons in their hands. But the current American president, Bush, completely lacks even the basic understanding that the wrestler and boxer had. He controls many weapons, yet he gives an order to go to war without any awareness of what he’s doing. He is the second worst president in American history, next to Harding.

What other current issues concern you the most?

TSURUMI: These days, some Japanese historians are, absurdly, trying to justify Japan’s fifteen-year invasion of Asia. From 1931 to 1945, the Japanese killed twenty million Asians under the policy of “Liberating Asia” from European colonization. How is killing people “liberating” them? Those attempting to justify the Japanese invasion of Asia are trying to gain ascendancy in Japanese academic circles through this argument. However, there is also the traditional Asian philosophy of virtuous people being the ones who record history. A typical case is that of the ancient Chinese historian, Sima Qian, who wrote the Shi ji (Historical Record) in the 1st Century, BC. Sima Qian was castrated because he opposed the Emperor, essentially to protect an innocent friend. But he finished writing the Shi ji even under the shame of castration. His inner virtue sustained him in continuing to write this great historical record of over 130 chapters. The concept of virtue allowing a person to record history is perhaps a uniquely Asian philosophy. But in Japan, this philosophy has been lost since the Meiji era, and now historians who completely lack virtue are taking advantage of the American government’s more open attitude towards Japan to push their agendas, such as trying to justify Japan’s invasion of Asia. I am completely outraged by this.

What do you think about the debate about the revision of the Japanese Constitution, especially Article 9. You’ve written, “When I read the Japanese Constitution, I thought that it was a good Constitution, even though it was forced upon us.”

We shouldn’t focus only on Article 9. Even if Article 9 stays in, the government could still control the people, because there is no clause in the Constitution about the individual rejection of military service. The important issue is that people should make up their own minds about what is happening around them, not blindly follow authority. In other words, we should not take the position that people who oppose the prevailing view are “wrong,” as I mentioned in the beginning of this interview. While the ideal is 100% tolerance, the reality is that not all people in this world live under democratic governments. Some live in totalitarian societies. How can people dissent under those kinds of systems? In the Western world, historically, people who were judged as “dissenting” were rejected by society, or even executed. One famous example of this is the Salem witch-hunts. Actually, now we understand that most of those believed to be witches had a genetic disease called Huntington’s Chorea. However, they were burned at the stake. In Japan, historically, people who broke the village rules were not killed but ostracized. In olden times, Japanese villages had a custom called murahachibu, which the people themselves created. It literally meant people were “eighty percent” excluded from the village, or hachibu. They were allowed to use the village’s water and receive funeral rites, etc., maintaining twenty percent connection, or nibu. If we don’t judge others absolutely, or at the minimum if we maintain an attitude that keeps nibu, or twenty percent flexibility, then we can resist oppression, even under totalitarianism.

How do you feel about the current Japan-America relationship?

The basis of my anti-war activity is my American education. So, even now, I have the strong belief that I am living as an American in Japan, although I have not returned to America since I was sent back to Japan in 1942. During WWII, the Japanese said to me, “A person like you should go back to America.” I can go back to America easily now, but now there is no America to go back to. In 1945, after the war, an old classmate from Harvard visited me and said, “America is now entering the age of fascism.” At that time, I disagreed with his opinion, because the America inside me was still romanticized. But when I listened to a speech by Bush after September 11, 2001, I realized that my old friend’s prophecy had completely come true.

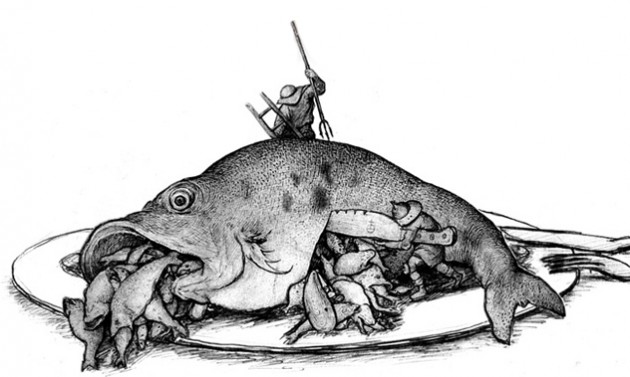

In the future, there will come a time when the concept of borders will disappear worldwide. At that time, what we currently know as America will be totally dismantled. And it will happen to Japan, even before that. The Japanese educational system has already completely fallen apart. For example, in order to move up in the Japanese bureaucracy, you’d better go to Harvard — even just for half a year. This is symbolic of how things are in Japan now — under the control of America. And I am in Japan. I am a tiny fish in the small fish called Japan, which is inside the big fish called America. It’s just like Bruegel’s painting, “Big Fish Eat Little Fish.”

In the borderless future, we should return to traditional Asian thought and philosophy. Why did Japanese politicians lose the ability to see themselves objectively after the Russia-Japan War? Because they completely lost the roots of traditional Japanese thought. Even though politicians in the Meiji era studied Western science and philosophy in college, they still maintained old Japanese ethics, studies, and customs from Edo as a reference point. Even after graduating from college, they always referred to those traditional Japanese concepts as a means of looking at themselves objectively. Ancient Japanese and Asian philosophy not only contain the concepts of tolerance and virtue, but also the concepts of liberalism and democracy.

For example, at the end of the Edo period, there was a Confucian philosopher named Yokoi Shona (1809—1869). His philosophy was that the purpose of a nation was to enrich the people, and a ruler who lacked the ability to govern a nation should be removed from office. This thought was based on Confucianism’s revolutionary thought. When Shonan learned of the American presidential election system, he was so impressed that he admired president George Washington as if he were a saint. So, we don’t have to insist on keeping the current Japanese Constitution. Because the seeds of liberalism and democracy already exist within traditional Japanese and Asian thought. The important thing is to hold onto the seeds of our tradition and let them grow, without limiting ourselves to lines made by current borders.

Oketani Shogo is a Tokyo-based writer and translator. With Leza Lowitz, he co-translated America and Other Poems by Ayukawa Nobuo, forthcoming from Kaya Press, for which they received the 2003 U.S.-Japan Friendship Commission Award from the Donald Keene Center at Columbia University. Oketani is currently writing a book of interrelated short stories looking at the effects of American culture on a group of young boys in Tokyo in the 1960s.

Artwork by Naomi Henig