Jean Miyake Downey

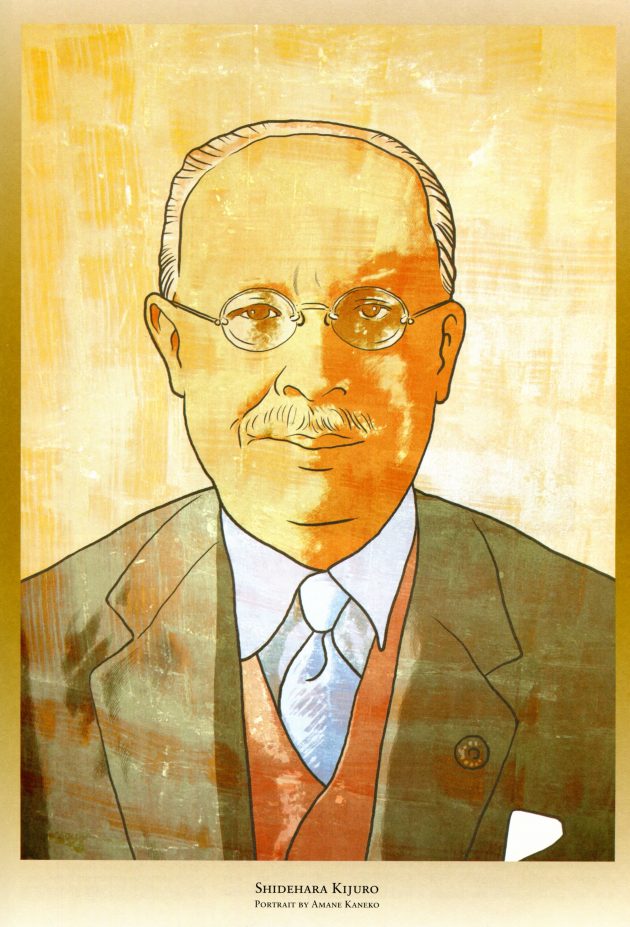

The notion that America unilaterally imposed Japan’s post-war Constitution and its famous peace clause, Article 9, upon the Japanese is a common misperception— not only in Japan, but also worldwide. In his forthcoming book Japan In The World: Shidehara Kijûrô: Pacifism and the Abolition of War.1 Peace historian Klaus Schlichtmann illuminates the true story behind Article 9, spotlighting the decisive role played by Shidehara Kijuro, Japan’s pacifist foreign minister in the 1920’s and second Occupation-era prime minister,

As chairman of the West-German world federalists from 1980 to 1992, Klaus started doing his own research on peace. That is when he stumbled upon the international law provisions in national constitutions, especially Article 24 of the German Basic Law, that delegate powers to the United Nations to further collective security and to outlaw war. This led him to Japan’s Article 9.

Enrolling at the University of Kiel, Klaus studied history, political science and international law, completing his master’s thesis on Article 9 and its presumed author, Shidehara Kijuro in 1990. In early 1992, Klaus went to Tokyo to deepen his research, paying daily visits to the Shidehara Heiwa Bunko (Shidehara Peace Library),2 then housed in the National Diet Library. At the end of his three-month stay, he was granted a scholarship from the Japanese-German Center Berlin and accepted as a visiting scholar at Japan’s Sophia University. He is presently working on a new book in German about Japan, and another one on the history of ideas of peace in India.

Please give us a short history of Article 9.

Most people are not aware of the fact that in the 19th century an international peace movement with the aim to abolish war already existed. The opening up of the West in the Age of Enlightenment to ideas and literatures of the Orient, especially the universalism and philosophies of India and China, had a definite impact on the European ideas of peace, justice and the international rule of law. Some of this found expression in the Constitution of the First French Republic and the general development of international law. The first Peace Societies were established in the United States and Great Britain in 1815 and 1816, respectively. These led to the convocation of the First Hague Peace Conference in 1899, which aimed at universal disarmament, and the creation of an international court equipped to resolve international disputes peacefully.

More than 100 years ago at the Hague Peace Conferences it was already understood that in order to disarm one needs to ensure peace and security by creating an international legal system. When a dispute arose countries would be prohibited from going to war and instead have to go to court. It’s amazing that this very basic idea and its history are not better known. The project failed, though — as did the Second Hague Peace Conference in 1907 — because a full consensus was required for the vote on binding international jurisdiction, without which disarmament was considered impossible.

Textbooks seldom mention the universal Hague Confederation of States (as some called the 1899 and 1907 assemblies) as forerunner of the League of Nations and the UN. However, the First World War, disarmament, mediation and arbitration continued to be predominant concerns of the League in the interwar period. Added to these was the idea of collective security. But the international court at The Hague was still an independent institution outside the League. With the advent of the United Nations in 1945, replacing the League of Nations, the court was integrated into the UN system, making it resemble more closely a supranational government; also, the UN Security Council opened itself to the members, to enable them to delegate powers to create an effective executive, something that was not possible with the League Council. So, the victorious powers (more or less the same nations that had favored binding international jurisdiction and disarmament at The Hague) had learnt from the mistakes of the League. In spite of that, collective security was never put into effect after the Second World War.

What does your research reveal about Shidehara’s pacifist beliefs and activities?

Having received expert legal training as a student at Tokyo’s Imperial University, Shidehara knew about developments in international and constitutional law. Japan had participated in both Hague Peace Conferences, and Shidehara was on his way to Europe when the first conference took place. Though he was not part of the Japanese delegation, he watched these developments closely. At the time of the second peace conference he was chief liaison in the Foreign Ministry in permanent contact with the Japanese delegation at The Hague. Being a young diplomat, he embraced the idealism in these conferences. As an intelligence officer in the foreign ministry during the First World War and chairman of the preparatory committee for the post-war peace conference, he became one of the best-informed foreign ministry officials with regard to international relations and the organization of peace.

One of the developments in the interwar period was the idea of including provisions in national constitutions to prohibit aggressive war. As ambassador to the United States from 1919-1922 Shidehara became acquainted with the American war-outlawry movement, which had come out of the First World War — the “war to end war” — and eventually led to the Kellogg-Briand Pact,3 endorsed by the U.S. Government. Although not a League of Nations member, the U.S. was intensely pacifist in the interwar period, and this too had an impact on Shidehara as he bacame one of the architects of the Versailles and Washington treaties,4 as well as the Kellogg-Briand Pact. As Foreign Minister between 1924 and 1931 Shidehara became known for his conciliatory and anti-militaristic policies. He was also one of the most prominent Japanese to extend peace feelers after 1937, aiming to end the war with China, and to avert war with the United States. After the war, when Shidehara was appointed Prime Minister, he seized the opportunity to place Japan in the vanguard of this movement for development cooperation and peaceful policies worldwide.

Your scholarship shows Prime Minister Shidehara proposed adding a peace clause to the new constitution. How did this happen and how was this history obscured?

After the war, Prime Minister Shidehara conceived the idea of a war-abolishing provision which should be included in the Japanese Constitution, and visited General MacArthur on 24 January 1946 to get his approval. MacArthur was enthusiastic and made sure that it was included, more or less with the wording Shidehara had suggested. Shidehara proposed it, and the Americans put it in. Both deserve praise.

However, the Shidehara Cabinet had previously and unofficially appointed a committee under Matsumoto Jôji to look into the question of constitutional revision. The Matsumoto Committee drafted two proposals, one that contained the usual articles providing for defense and a defense ministry and another containing no such provisions. Shidehara was not interested in drafting an entirely new constitution; however, he had asked that the revised constitution not contain any clauses pertaining to war or the military. When it transpired that the Matsumoto Committee was going to present its draft against Shidehara’s wishes with the military clauses, the draft without the military clauses was leaked and prematurely published by the Mainichi Shimbun. A Mainichi journalist, Nishiyama Ryûzô, found the draft in the room where Shidehara sometimes took naps. Nishiyama suggested that Shidehara may have planted the document there, but later retracted his statement. All this led to the Americans working on a draft constitution of their own, which was eventually adopted — although it too was based largely on a draft by the Japanese Constitutional Research Society (kempô kenkyû kai) under the scholar Suzuki Yasuzô. The history of Article 9 and collective security both became obscured by the Korean War and then the Cold War.

Detractors argue that Japan must revoke this clause so that Japan can become a ‘normal’ (meaning fully militarized) nation. Why is a revocation so important to advocates of unlimited Japanese militarization?

First of all, military power is still one of the most important features of national sovereignty. Nation-states are reluctant to agree to limitations of their sovereign powers if they don’t know where they are heading. But the UN Charter actually gives quite a clear direction when it talks about member states having to confer primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security on the organization (Article 24) and abstaining from the threat and use of force (Article 2, 4). Although the blue helmets wear the UN emblem, they are not part of the UN system of collective security as originally conceived by its founders. Now, however, everybody is pretending that this is the best collective security we can get. It doesn’t require any limitation of national sovereignty, even though everybody knows that an international organization can only be effective to the extent that its members agree to delegate or limit their sovereign powers in favor of the organization.

Among those who want to change Article 9 are hard-line politicians who believe military power is the best and most appropriate means to project and serve Japan’s national interests. They are the revisionists referred to in Japanese as the advocates of kaiken. Then there are the honest pacifists who believe that the Self-Defense Forces are unconstitutional, but since the ideal of Article 9 is unattainable it would be the honest thing to change Article 9. Among the advocates of kaiken are some who merely want to change the interpretation, not the words of the peace clause (kaishaku kaiken). They are similar to those who also want to keep the wording, but pass supplementary legislation to make Article 9 conform to reality (creative constitutionalists, or advocates of sôken). Then there are those who, in view of the little progress that is being made, merely want to promote constitutional debate (ronken). However, the majority of Japanese [80% in a May, 2007 poll], and many politicians, continue to be advocates of goken, and they insist on a strict and ideal interpretation of Article 9, in view of the continuing possibility that the UN system may come into force one day or because Article 9 has served Japan well and contributed considerably to peace and security in the region.

Some critics of Article 9 say that the clause is meaningless because Japan is already militarized, spending $46 billion on defense in the last fiscal year.

Since Japan now has a Defense Ministry, the Self-Defense Forces have been institutionalized somewhat. They are no longer a mere provisional agency, as had been the case for sixty years. But there is nothing in the Constitution yet that refers to a defense ministry. So there still is a chance to follow up on Article 9. The original intent, the core of the article is still intact — a collective security that would enable all countries to embark on the journey from an armed to an unarmed peace, and to disarm. Without implementing UN Article 106 it is not legally possible to enable the Security Council “to begin the exercise of its responsibilities” and lawfully take “action on behalf of the Organization.” The whole point is that some country or countries have to follow up on Article 9 to get Japan out of its one-nation pacifism predicament. So far the Security Council has no legal basis, except that it is enumerated in the Charter as one of the six principal organs to which the member states are supposed to delegate primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security. Whereas “it can decide in accordance with what it thinks is expedient,” as John Foster Dulles once put it, in fact, “no principles of law are laid down to guide it.” So, the process of delegating powers to the United Nations must be initiated at the same time. I hope my country, Germany, will eventually get around to taking this important step to empower the UN. We have a lot of credibility, you know, and it’s in our Constitution.

Do any other countries have peace clauses similar to Article 9 in concept and in implementation?

Costa Rica’s anti-war Article 12 is quite similar. If we take the limitation of national sovereignty as the most important part, until the Korean War in 1950, France (Preamble, para 15, 1946), Italy (Article 11, 1948), Japan (1947), Costa Rica, India and Germany (all 1949) had newly adopted constitutions, aiming at in- ternational cooperation, peace and security, and promising to delegate or limit sovereign powers to achieve this. The Korean crisis was the opportunity to implement these clauses — and Article 106 of the UN Charter, as the Russians insisted — and pass legislation to transfer sovereign powers to the UN Security Council. But nothing happened, and instead Japan and Germany rearmed. Later, the Danish (Article 20), the Spanish (Article 93), the Greek (Article 28), Dutch (Article 92), and Belgian (Article 25) Constitutions and others also adopted clauses for limitating or delegating sovereign powers to the UN. The French Constitution is also especially strong on this point.

Most Western scholars and even some peace activists believe the disarmament part of Article 9 is its most important feature. That is unilateral disarmament, also found in Article 12 of the Costa Rican Constitution, which reads: “The army as a permanent institution is abolished.” However, Article 12 also states that military forces “may … be organized under a continental agreement or for national defense.” If we read this conditional clause carefully, it appears that Costa Rica does not differ very much from Japan, except that it has been able to afford to forego — unlike Japan — maintaining national self-defense forces.

Most serious researchers would agree that it is not possible to disarm into a vacuum, because this would risk causing significant security gaps. The pacifist and 1911 Nobel Peace laureate Alfred H. Fried said that “armaments are reasonable as long as the system is unreasonable.” Article 9 aims at a system that can do away with the institution of war. Limitation of national sovereignty is the main part in the Japanese Constitution, not the disarmament part.5 But war is government business. I was recently told by a prominent peace and disarmament campaigner that general and complete disarmament is not going to happen, because of the arms trade. In this respect, too, Japan is different. There is no significant arms industry or trade.

The Bush administration sought to integrate the militaries of many nations— including the UK, Canada, Germany, Poland, as well as Japan— under US hegemony. This system is built on a framework of ever-increasing armaments. How can we demilitarize and shift towards a global peace economy?

I believe the US Government, especially the new administration under President Barack Obama, would be relieved if the UN system were to go into effect. In my view this is mainly a task for the Europeans. Article 9 is a precedent and — if followed up — a readily attainable step toward a comprehensive system of international security under the United Nations. This step would allow national governments to make specific and compatible moves towards creating a general and sustainable framework for disarmament. By the way, Article X of the US-Japan Security Treaty stipulates that the treaty will become obsolete if and when the UN system of collective security becomes operative in the Japan area.

A realistic policy would also have to aim at a comprehensive global disarmament treaty, for which an obligation already exists. What I hear from some activists, however, and especially government representatives, e.g. the members of the German sub-commission of disarmament and non-proliferation with whom I have been corresponding, is that we should be happy with small steps and limited projects like the landmine treaty and cluster bombs agreement. But I think you have to do both. A global disarmament treaty along the lines of the McCloy-Zorin Accords3 (unanimously adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1961) would not be too difficult to achieve, if the understanding is that all have to pool their sovereign responsibilities to create an international organization, that has enough power to abolish war. You really should check out the 1961 agreement, which President Kennedy introduced with these memorable words: “Today, every inhabitant of this planet must contemplate the day when this planet may no longer be habitable. Every man, woman and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by accident or miscalculation or by madness. The weapons of war must be abolished before they abolish us…”

Notes:

1. Lexington Press, March 2009.

2. The Shidehara Peace Library was integrated into the general library in the early 1990s.

3. The Kellogg-Briand Pact (also the Pact of Paris), signed on August 27, 1928, was an international treaty ‘providing for the renunciation of war as an instrument of national policy.’ Although it did not achieve its ends, it did influence many subsequent policy-makers. It was named after the American Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand.

4. The Washington Conference was one of several naval disarmament conferences in the interwar period; it resulted in several treaties that included rules and regulations for maintaining peaceful relations in the Far East. The Versailles Treaty at the end of World War I produced the League of Nations. To some Americans the League’s Covenant, which was part of the Versailles Treaty, did not go far enough toward abolishing war.

5. The Costa Rican Constitution merely envisages “transferring certain jurisdictional powers for the purpose of realizing common regional objectives” (Article 121), so, their emphasis and scope differs. Japan’s disarmament is constitutional, which means that the SDF has been a temporary, ‘self-help’ arrangement (which the Costa Rican Constitution also allows), legitimate only until the UN system starts to operate, strictly speaking.

6. The McCloy-Zorin Accords between the US and the USSR form the basis of all negotiations and treaties regarding nuclear, general, and complete disarmament under effective international control.

UN Charter

Article 24: “In order to ensure prompt and effective action by the United Nations, its members confer on the Security Council Primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security…”

Article 43 : “All members … make available to the Security Council … [police] forces, assistance and facilities [etc.] … for the purpose of maintaining international peace and security … The … agreements shall be negotiated as soon as possible … and shall be subject to ratification by the signatory states in accordance with their respective constitutional processes.”

Article 106: “Pending the coming into force of such special agreements referred to in Article 43 as in the opinion of the Security Council enable it to begin the exercise of its responsibilities … [the permanent members are able to merely] consult with one another…”

Constitutional clauses (peace constitutions)

Para 15 (France, Preamble 1946): “On condition of reciprocity, France accepts the limitations of sovereignty necessary for the organization and defence of peace.”

Article 11 (Italy 1948): Constitution “renounces war” and “agrees to limitations of her sovereignty necessary for an organization which will ensure peace and justice among nations…”

Article 24 (Germany 1949):

“(1) The Federation may by legislation transfer sovereign powers to international organizations. … (2) With a view to maintaining peace the Federation may become a party to a system of collective security; in doing so it shall consent to such limitations upon its sovereign powers as will bring about and secure a peaceful and lasting order in Europe and among the nations of the world…”

Article 20 (Denmark 1953): Constitution aims at an “international legal order and cooperation” among nations, for which powers can be transferred “through a Bill, to a specifically defined extent” to the UN.

Other Treaties

World Federation (1949 Resolution in both Houses in the US):

“Resolved by the House … that it should be a fundamental objective of the foreign policy of the United States to support and strengthen the United Nations and to seek its development into a world federation open to all nations with defined and limited powers adequate to preserve peace and prevent aggression through the enactment, interpretation, and enforcement of world law.”

The McCloy-Zorin Accords (Principles) of 20 September 1961 (http://www.nuclearfiles.org/) have been “codified” in Art VI of the Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1968, which stipulates that all signatories will “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race … and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

US-Japan Security Treaty (Nichi-Bei Anpô), Art X: “This Treaty shall remain in force until in the opinion of the Governments of Japan and the United States of America there shall have come into force such United Nations arrangements as will satisfactorily provide for the maintenance of international peace and security in the Japan area.”

From issue KJ72 (Article 9 and the Imagination) published June 10, 2009

Jean Miyake Downey, KJ contributing editor, was deeply involved in the creation of this special issue on Japan’s pacifist constitution and its implications.

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013