Kazuaki Tanahashi is a Japanese calligrapher, translator of the Zen master Eihei Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō (The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye), and a deeply committed peace worker, who is active in the United States. Known also more simply as Kaz, he approaches all of his work with both thoughtfulness and fluid spontaneity. His methods, emphasizing the inherent power of each moment, and of every breath, are informed by his time as a student of Aikidō founder Morihei Ueshiba, as well as his long immersion in Dōgen’s teachings.

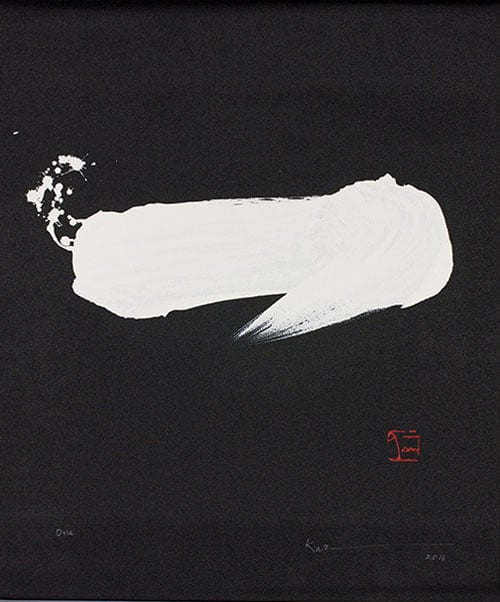

These influences, together with his experiences in wartime Japan and post-war America led to the development of Kaz’s distinctive brushwork, in particular his interpretation of traditional ensō. These hand-drawn circles are commonly seen in Japanese calligraphy, usually created through a single, flowing brushstroke that represents a moment in which the mind creates freely. Ensō have a strong element of wabi-sabi, embracing the incompleteness, roughness, and impermanence of things, a recognition that in turn reveals the raw, organic beauty of life. These strokes reveal a surrendering of mind and body to the transience of things, the mark upon the paper a tangible representation of a moment now passed, a feeling relinquished.

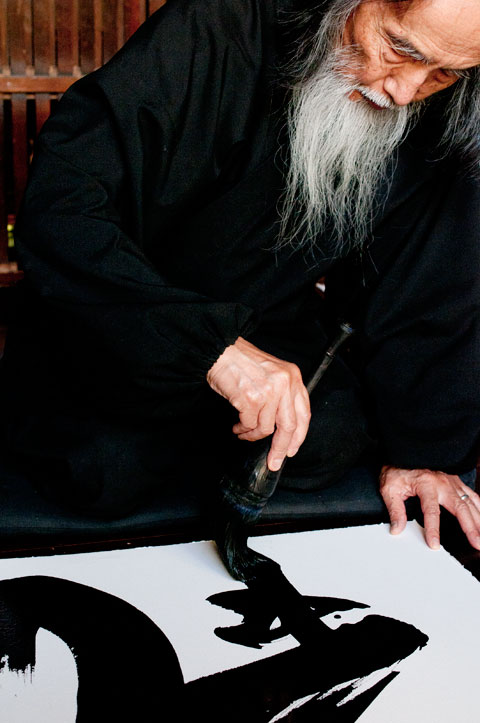

Kaz channels and reinvents the deep symbolism of ensō through his use of immense brushes—some even larger than himself—freeing his painting by ceding some elements of physical control. This freedom is poignantly enhanced through his thoughtful use of color, scale, and shape; there is a quietness to some of his works, a subtle and lingering feeling, while others are powerful, burning, and chaotic. But all are united in their existence as manifestations of something that stirred within Kaz, a feeling that was recognized and embraced without inhibition, then expressed through his technical grace.

“We all have a brush,” Kaz writes in his book, Painting Peace: Art in a Time of Global Crisis (2018). “It starts within us and we each leave our mark on this world in our own unique way. To see that this is within all of us is also a point of unity.”

Below is a conversation the KJ team had with Kaz on his art, activism, and philosophical insights. A number of Kaz’s ensō and calligraphic works are also featured within our Wellbeing issue (KJ95), which can be ordered here.

KJ: What is your earliest memory of your teacher Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikidō?

Kaz: The first essay in my book Painting Peace is called “Years Before Pearl Harbor.” It’s a story about my father, who was a staff officer in the imperial military headquarters. He was literally a war planner. He received a message from a Shinto deity that said “If you start war with the US, Japan will lose and be confined to small islands.” So my father was worried.

At that time it was Japan’s policy to avoid war with the US, so my father talked to various top officials including the prime minister, army minister, the Emperor’s brother and so forth, and then his teacher of Aikidō, Morihei Ueshiba, who supported his endeavor. My father got a big budget from a secret service fund, money you don’t have to report. Japan was choked that time by sanctions because Japan had occupied some parts of Indo-China because of needing oil for airplanes and all that. That created big hostility in the US, so there was a sanction called the ABCD line: America, Britain, China, and Dutch. That was the situation and eventually the government decided to strike Pearl Harbor. So my father was sent to Europe to study the weapon systems of Hitler and Mussolini. And Ueshiba-sensei, friends and family were saying goodbye to my father when his train was going westward.

Is that what made you decide to become active in peace?

I was about eight years old. So I remember that, but I didn’t know about the secret negotiations. Morihei Ueshiba was teaching about peace after the war. My father started a Shinto organization called “Church of Peace” after the war. So I have two teachers. But before that, the war was very difficult. One city, another city—bombed and burned. And there was a severe shortage of food. I suffered so much and don’t want any children in the world to experience such pain. This is the basis of my commitment for peace.

When you went to the US the Vietnam war was happening?

I first visited in 1964 and ‘65, when the Vietnam war was happening. Then I went back to San Francisco in 1977. That was the time of the Cold War and the nuclear arms race. Especially in 1979 and ’80 it became so bad.

That was also the time when you were translating the Zen master Dōgen?

Yes, I was living in San Francisco when I felt that the world might not exist when I would wake up the next morning. I realized that the book I was creating, the translation of Dōgen’s work, might not be published at all. There might not be readers, there might not be people in the world. That’s when I started organizing works to reverse the nuclear arms race.

“Dōgen’s essential teaching is miracles of each moment. To be fully positive, to be confident of your power to serve and make large-scale social transformation.”

You’ve written about your translation of Dōgen—it was very important for you to translate it to an American vernacular, like the American context.

Not necessarily American, but making translation natural for English-speaking readers—we wanted to create an illusion that Dōgen had taught in English.

Can you tell us about that whole process? How you decided to translate that and what it took to actually complete it?

In my mid-20s I was a beginning artist and looking for a spiritual guide, so I went to Existentialism, like many others, and then I realized that to be a good artist in an existentialist way, you had to be in despair or bored. It didn’t work for me. Then I was looking around and ran into Dōgen’s writings. I was fascinated. I had a show in 1960 in Nagoya. There was an old man who would come every day and we became friends. I realized that he was a good scholar on Dōgen study, so I said to him—his name is Sōoichi Nakamura—”I know Dōgen is great, but people don’t understand. If you would translate it into modern Japanese, that would be a great help.” He said, “Yeah, I can do that. If you help me.” So we started working.

I didn’t have any background on Buddhist studies, so I had to study Chinese, Buddhist philosophy, Zen language, Sanskrit and so forth. It took us about seven years to translate the entire 96 chapters of Dōgen’s lifework, Shōbōgenzō, which can be translated as “Treasury of the True Dharma Eye.” In the meantime, I visited North America in ‘64 and ‘65 and there I translated a few essays of Dōgen into English. Later I wanted to translate together with actual practitioners of Zen, instead of doing it in my study in Japan. I was invited by the San Francisco Zen Center and started working in 1977. I worked there for 7 years. Then after I became independent, they supported the Dōgen translation project, just a single book creation, altogether for 33 years. They were not only giving me money but sending me serious Zen practitioners and teachers to translate with me. It took me in total 50 years, from 1960 to 2010.

What do you think was the most difficult part of translating that?

I first paraphrased medieval Japanese into contemporary Japanese. It worked in some cases but it didn’t in other cases. Then after translating a few essays into English, I realized that we needed to deconstruct the original sentence structure and find the best counterpart expression, in this case in English. Sometimes it’s not sufficient to follow the grammatical structure but, instead, to find a better way to express similar meanings in another way while maintaining compatible strength and poetry of the original.

Also, I think that always in any language or any literature, one word or one phrase, has multiple meanings with multiple shades, but you need to choose one in the process of translation. So in a way translation becomes clear and easy to understand, but actually you lose a lot of richness that was in the original. Also, in the new language, some extra meanings or nuances are added. In this way, translation can be seen as an act of being defeated from beginning to end. On the other hand, translation can help transform the consciousness of people, language, and culture.

“Translation can be seen as an act of being defeated from beginning to end. On the other hand, translation can help transform the consciousness of people, language, and culture.”

In regards to doing peace work and anti-nuclear work, often in these situations you’re organizing people to take on power that’s so much bigger than you. You’ve trained in Aikido, which is in that same spirit of being strong against larger opponents or having to confront larger opponents. Have you learned any lessons in your work with peace work or environmental work?

In Painting Peace, there is an essay called “Amazing Turn.” It describes an effort to stop one of Japan’s top priority national projects: plutonium-based electricity generation. Someone came from Japan and said, “No one in Japan can stop it, can you help?” We were just seven hippies and artists living in San Francisco Bay Area. Along with the painter Mayumi Oda, we started an organization called “Plutonium Free Future,” and I was sent to Rio de Janeiro [UNCED “Earth Summit” conference, 1992] and organized an international campaign. You may remember that there was a plutonium shipment from France. We called it a “floating Chernobyl.” There was a big outcry against the plutonium shipment in the international community, and a lot of countries like Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia and Malaysia banned the boat from their territorial waters. When it arrived in Japan, the opinion in the Japanese government split.

We had hired an environmental lawyer, a US lawyer but he used to be an advisor to the Japanese cabinet, so he knew how to deal with the Japanese government and he was an Aikidō practitioner, so he knew how to apply pressure—a small but very effective pressure. Eventually the Japanese government collapsed, not because of us, but because of corruption. One of the people who had been communicating with us from Japan became the minister in charge of science and technology. He held the first public hearing about the long-term nuclear energy development and cancelled a series of multi-billion-dollar projects. Japanese people didn’t say “We will cancel it,” but they said, “We will postpone it indefinitely.” Thus, we made a big throw.

In Aikidō, the other guy may be big and strong, and you may be thrown down. But you have a chance to throw down the opponent, too. We had the nuclear arms race, that was probably the worst scenario of global collective suicide that we had faced as humanity, and we reversed it. So I feel that no situation is impossible to change.

I would like to talk about your brushwork. There’s not a tradition of using color so much in Japanese calligraphy, but you tend to use a lot of it in your work. How did you get into color?

I often draw ensō. One time I was invited by Zen Hospice in San Francisco to do a large ensō and I thought a black circle might not be so cheerful for people who were facing death. So I started using colors. The United States is a society of diversity. I believe a multi-color ensō would be suitable in this context.

So you first put colors on paper or canvas and move the brush over it?

That’s right. In one decisive stroke, without going back.

You don’t meditate first?

For me, every activity, every moment is meditation.

You’ve worked with Dōgen for so long and in translation, how does Dōgen come into your personal day-to-day life?

Dōgen’s essential teaching is miracles of each moment. To be fully positive, to be confident of your power to serve and make large-scale social transformation.

Lastly, do you have any advice for young people who are starting to do peace work or anti-nuclear work in grass-roots organizations? Any lessons you’ve learned in gathering people for a common cause?

I think the important thing is to work together with others, to have good vision and an outstanding strategy. Try to find the most effective way with the least effort for the maximum result.

Kazuaki Tanahashi is credited as author, editor, translator of over 40 inspirational books that include:

Painting Peace: Art in a Time of Global Crisis. Boulder, Colorado, Shambhala. 2018.

Heart Sutra: A Comprehensive Guide to the Classic of Mahayana Buddhism. Boston and London, Shambhala, 2014.

Brush Mind. Berkeley, California: Parallax Press, 1990.

Penetrating Laughter: Hakuin’s Zen and Art. New York: The Overlook Press, 1984.

Enku: Sculptor of a Hundred Thousand Buddhas. Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala, 1982.

You can learn more about Kaz and his work by visiting his personal website: BRUSHMIND.

Header photo by Mitsue Nagase www.mitsuenagase.com

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013