Peter Handel speaks to Andy Couturier, author of "The Abundance of Less"

Back in 1990, Andy Couturier was unexpectedly introduced to a dispersed community of Japanese “pioneers” of simple, sustainable and personally meaningful lifestyle. Many, inspired by years of residence in Nepal or India, lived a life reminiscent of T’ang Dynasty recluses. In 1999/2000 he interviewed them for a column in The Japan Times, and contributed several longer articles to KJ, eventually publishing A Different Kind of Luxury, a book recently updated and re-issued (by North Atlantic Books) asThe Abundance of Less: Lessons in Simple Living from Rural Japan (available at Amazon here).

Journalist and KJ contributor Peter Handel talked with Andy Couturier about the book, the people in it and their priorities in living satisfying lives.

Peter: In The Abundance of Less you profile a group of people who live in the Japanese mountains in a way that repudiates much of the values of capitalism. They are antimaterialistic, community-oriented, and value creative pursuits. Some are more explicit about their rejection of the market economy than others, but all are clear that this was a conscious path. Can you give us some insight into how they’ve been able to live these kinds of lives in modern Japan?

ANDY COUTURIER: First of all, almost all of their decisions are driven by the question: “Does it cost money, or not?” Since they want to be self-reliant and as free as possible, they try to make conscious choices to radically reduce the amount of cash they need. For example, one man, Koichi Yamashita, has a PhD in philosophy and used to teach at a university. But, in order to live in deeper contact with the natural world, he quit that job and doesn’t complain about doing paid work like pulling weeds in the hot sun on a tea plantation. Another tip might be how the same man, who grows all of his own food, advises other farmers to “not be greedy with the soil.” Another clue to the way he avoids the market economy would be when he says, “What I have available to eat, that is what is for dinner.” One woman, Atsuko Watanabe, suggests how each of us can make such a radical change in our way of thinking when she says: “Most people don’t have the time—don’t make the time to slow down and think deeply about the reason they are alive.” She also contemplates often on the lives of the villagers she encountered in India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, and then compares her life in Japan to theirs: “Even though in Japan, we are poor, I feel that I have more than enough.”

How did you meet them and decide to write about them?

I first met several activists in a small city in a rural region of Japan back in 1990 and I was simply pleased to be connected with progressive folks in what seemed like an overwhelmingly conservative country. But quickly I realized that there was something quite different about them, compared to the crowd of activists I had known and was part of back in the US. There seemed to be a lack of striving or grasping to them. They protested government actions—whether it was nuclear power plants, huge dam projects or the destruction of tropical rainforests by Japanese corporations—from a sense of it being the right way to spend their lives, rather than from a sense of righteousness or coming from some old injury in their family or psyche. It seemed profoundly healthy, even though their chances of winning a court or legislative battle was far less than ours in the States was. But the true eye-opener came, for me, when one of those activists, Atsuko Watanabe, invited my partner and I to visit her “in our old farmhouse in the mountains, where we grow our own food.” I wanted to write about these people because I thought they could be a true inspiration to both progressive and environmental people in the West, but also perhaps help more “mainstream” people see that their way of living might not be bringing them happiness, and might be doing a lot of destruction along the way.

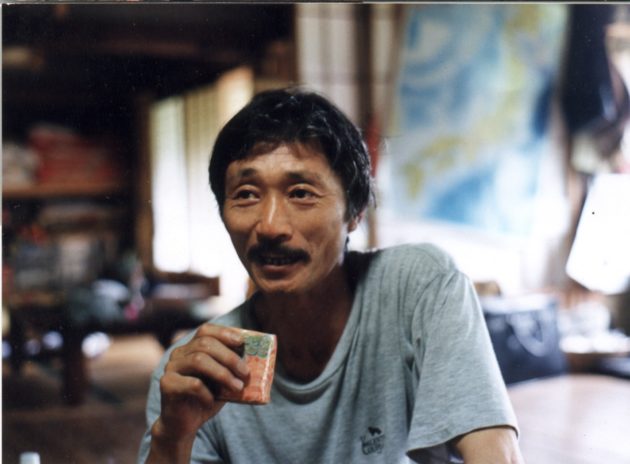

You profile the potter San Oizumi, who calls himself an anarchist. How does he see his life as exemplifying some of the core anarchist principles?

I’ll start with a quote from him. When I asked him what it means to an anarchist in Japan, he replied, “Of course you don’t understand Japanese anarchism. That’s because each one in Japan—and each one anywhere—is different.” For him, I think I can say he’s opposed to all kinds of authority. So, when he was invited to France to speak out against nuclear power by a leftist group, and everyone was cheering wildly, he found that very disturbing and rejected it. “I felt like a demagogue,” he said. Whether as a potter or an activist, he doesn’t participate in the hierarchies of any of the groups he joins. Nor does he give special respect to anyone in a high position. As he says, he does not want to give up “the opportunity to think for himself.” According to him, it’s too valuable a thing to be wasted that way.

Another person, Asha Amemiya, says that “If too many people say: ‘It’s good enough just as it is’ then the system—capitalism—stops turning.” What does she mean by this and how does her life reflect this statement?

The way she puts it, “if you don’t have a lot of unsatisfied people, the economy stops dead — doesn’t it?” And she uses the example of when you spend a lot of money on a new computer and then another one comes out “that’s even better. It has all kinds of improvements, right? So, of course you want it. But, since you want it, you have to work even more. But, if you keep chasing that kind of thing, there’s no end to it. For me, what I have is enough. I don’t need any more.” Another example might be that by some standards, the old house she lives in “needs repair.” But she values her freedom too much to chase after the money it would take to fix it. She’s happy with her life “as it is.” She claims that if too many people were satisfied with how their lives are the capitalist system would “stop dead.”

While the people whose lives you detail in your book are a varied bunch, all value self-sufficiency, particularly in that they grow their own food and this is really central to their lives. Tell us about what you learned with respect to this?

This was a deep learning for me, and it’s hard to sum up in a few words. What I can say is I believe total “self-sufficiency” is not possible. We are all dependent on so many other people, and that’s something to be celebrated. However, the self-reliance of providing for your own needs as much as possible is not only deeply satisfying, but it connects you to the earth, the seasons, your own body, your mind, in terms of how to figure out how to grow food or repair something. It also connects you to thousands of years of tradition and wisdom regarding our relationship with plants.

To varying degrees the people you profile work for money, although none work a full-time job. One or two talk about living with this contradiction. How do they manage these kinds of contradictions in their lives? How do they keep the need to work for money to a minimum?

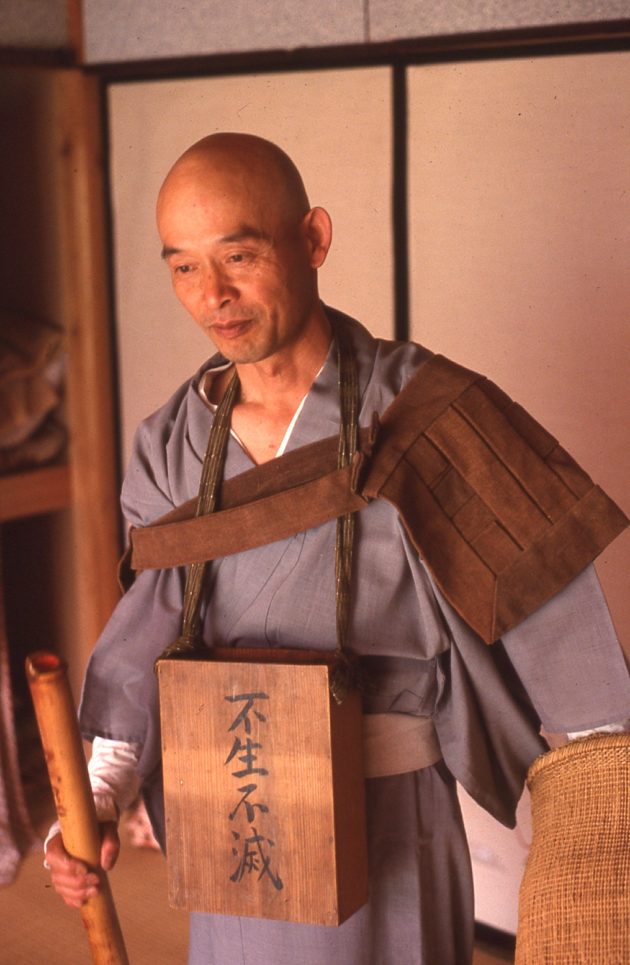

I think all mature people know they have to live with some level of contradiction, especially in our current society. The question is: how do you use your own creativity and resourcefulness to provide for your needs without relying entirely on the cash economy? Part of it is also about building your capacity to control your own cravings and desires, particularly as is taught in many Buddhist traditions. Another thing I noticed about the people I wrote about is that they do not use money to entertain themselves. One man, Kogan Murata, plays the giant bamboo flute. He only plays seven songs—all of them hundreds of years old. He doesn’t make up new songs for himself, nor does he play popular melodies. He finds a tremendous richness just by delving deep into those seven melodies. I think that can be a metaphor for a lot of things. By reducing their desires as much as they can, they are by so doing, reducing the level of contradiction in their life.

Even those of us who don’t think of ourselves as materialistic often strive to earn as much as we can for the sake of our kids. We want them to have good lives and not feel deprived. Yet, many of the people whom you profile have raised happy, healthy kids with very little money. Tell me about that.

I did interview a number of these people’s kids and I think a lot of them really enjoyed the pleasures and joys of country life: raising chickens and having lots of cats and being free to wander and play in the mountains and rivers. One boy gets books from the library on how to make bamboo crafts and makes all kinds of toys for himself. And remember this is in twenty-first century Japan, full of video games. Those kids developed a lot of resilience by learning to entertain themselves instead of using money to buy gadgets, etc. I should also mention that in modern industrial Japan, a lot of families still depend on the father bringing in the majority of the income. (For reasons, that I, as a feminist, have a lot of trouble with—but that’s another story.) However, in all of the families that I interviewed, these kids had a lot of time together with their parents when they were growing up because neither the mother nor the father had to leave for a faraway job. So, that’s a great way for kids “to have good lives,” as you say. As for after they leave home after high school, one young woman who I interviewed was frustrated that she was not able to go to a more expensive university where she could study the Hindi language. Even so, currently she is living and teaching in India. So, while she might have been frustrated as an early-20s person that her parents didn’t have enough money to send her to that university, I think she has had a lot of satisfaction in her life anyway, and now has Hindi and Indian culture as an integral part of her life, even if she didn’t study it an expensive university in Japan. So while I am not a parent, I would say that providing children with every possible thing that money could buy so that they “don’t feel deprived” may not be the best way to provide them with the richest or deepest life.

You could probably see how someone could read this and think, “well, that’s great if you’re going to go live in the mountains of Japan, but what could this mean to my life in the West?” What would you say to that?

Well, this is exactly the question I pick up and examine in detail in the Afterword of the book. Yet I will say that wherever you live, trying to make radical reductions in how much you consume can make a tremendous difference in terms of how satisfied you are, and how much damage you do to other people, and to the earth. Some things that make this radical reduction easier in the West are not insisting on living in the hippest, most happening (and high cost) location. Everyone I profiled lives in a remote rural area. This is very possible in the United States. A second thing would be to try to de-industrialize our own way of thinking. That’s a subtle but important thing. I don’t have space here to explain that in enough detail. A third thing would be insisting on slowing down, no matter what the blowback you might get from the culture or people around you. I think it is crucially important to put aside long chunks of time on a regular basis to reexamine your own life and whether you are living true to your values—and also using that time to figure out the practical side of how to slip the noose that society constantly tries to put around you. In the book, I go into each person’s story about how they did that (instead of providing a set of cut-and-paste tips or tricks or “hacks.”) I think stories are more inspiring and useful. The key thing about all of these changes is that they don’t make life miserable. I have found, meeting these amazing Japanese people, they make life richer, deeper, and more meaningful. And isn’t that kind of satisfaction what we are all truly hoping for?

Peter Handel is a freelance writer living in Northern California.

Photos by Andy Couturier

http://www.theabundanceofless.com/