I began to translate the Emperor Meiji as a sort of fluke. Fresh out of grad school at Columbia University, I had a Fulbright to research modern Japanese poetry at Keio University in Tokyo. I was there from 1962-65. Now 1964 was an important year for Tokyo. The Olympics were held there, and some of the stadiums were built on the grounds of the huge Meiji Shrine, a Shinto complex in downtown Tokyo. That’s where the souls of the Emperor Meiji and the Empress Shoken are enshrined. They are still considered by many to be Shinto deities.

Shintoism and sports were always considered to be compatible — from ancient times archery contests and sumo wrestling tournaments were often held at Shinto shrines. It is not strange that the most important games in modern times would be held in the grounds of one of the more important shrines in the country. And it is not surprising that the (now) Chief Priest Shinichiro Takazawa, in his position as Gonguji, or Assistant Chief Priest, wanted to share some of the poetry of the Emperor Meiji with the international guests of the Olympics. The Emperor Meiji had welcomed foreigners into Japan after centuries of isolation. Many of his 100,000 poems written during his lifetime dealt with international themes. Asked if I would provide the translations, I readily accepted.

Meiji Shrine

Before I began the actual translation I was given a tour of the Meiji Shrine. In the iris garden that was designed, in part, by the Emperor Meiji himself, Priest Takazawa turned to me suddenly and asked in Japanese, “Meiji Tenno ni aitai desu ka ?” I wasn’t totally sure I understood. It seemed like a strange thing to say — “Do you want to meet the Emperor Meiji?” I think I said, “HUH?” But then covered up my bewilderment by saying, “Dekireba…”: (If it is possible….) I did know the Emperor had been dead since 1912…But this was Japan, where things are not always clear…

So, I was blessed, and purified. I had the haraigushi, a wand of pure white paper and sacred sakaki leaves swished over my head, with a lot of chanting. I was then led through a gate, back towards the inner sanctum, a place reserved for only the highest Shinto priests. A large Shinto shrine has three main sections: the haiden (where most people worship), the heiden (an area closer in where usually only Shinto priests go to perform rituals or offering) and the innermost area called the honden where the shintai (which Kenkyusha’s New Japanese-English Dictionary. defines as “…an object of worship housed in a Shinto shrine in which the ghost of a deity is traditionally believed to dwell.” I later learned that the priests approaching this area should be ritually pure. No meat. No sex (for a day or two anyway), and when they really get close they are even required to wear surgical masks.We were heading for the very depths of the shrine, the honden. Yet I wasn’t asked to do all the the required ritual. They had other ways, I found, to keep me from polluting this sacred space.

At the door to the inner sanctum I was handed a bowl the size of a wash basin. I thought, perhaps, it was for washing my face. But no! It was for internal purification. Sacred sake! About a quart of the stuff, if I remember right, was sloshed out into my big wash pan by a Shrine maiden dressed in red and white.. I remember Priest Takazawa telling her, “Give him a BIG one. He likes the stuff.”

Well, my knees were buckling a bit when I left the gate to enter a dark dark room. I think I was about half blind anyway. I remember I was told to look deep into a dark alcove, maybe another little room. I think I saw an old hat or something back in a dark closet-like place. I instinctively bowed. Priest Takazawa began the introduction, “This is Harold Wright. He’ll be translating your poetry…”

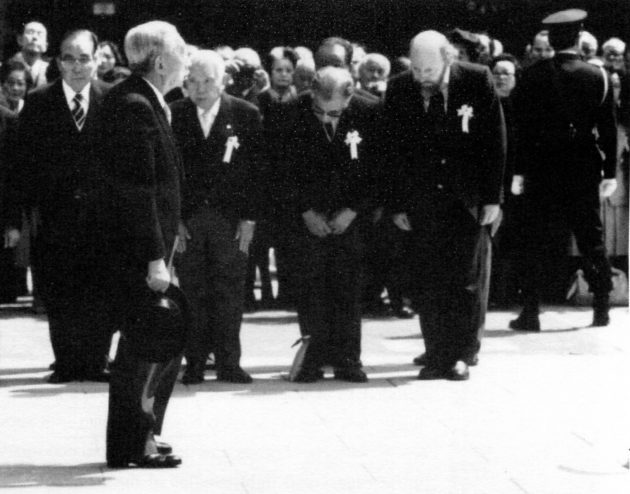

Harold Wright meeting the Showa Emperor

Harold Wright meeting the Showa Emperor

I said, “Hajimemashite. Doozo yoroshiku onegaishimasu.” I don’t really know if His Majesty said anything back or not. The sake was really beginning to work, and I was feeling pure enough and brave enough to also add, “I’d really appreciate your help on this project…I’m kinda new at this sort of thing…”

Altogether I translated nearly 300 of his poems at various times and for different reasons. I was invited back to the Meiji Shrine to do a small book on the 70th anniversary (a very important anniversary) of the death of Emperor Meiji, in 1982, and of the Empress Shoken, in 1984. These two books were for mass distribution by the shrine itself.

Translating these little books, each containing less than one hundred poems in total, was one of the most difficult and exacting translation projects I have ever encountered. Each word was scrutinized by a committee of Shinto priests and traditional tanka poets. My work was read and commented on by even the Grand Chamberlain of the Imperial Household. I don’t know if the Emperor Hirohito himself ever read my work, but I was told, “His Majesty appreciates what you are doing for us.” My hardest critic was one of the professors of Shintoism at Kokugakuin, the national Shinto University in Tokyo. He had done his graduate work in divinity at the University of Chicago. To him the Emperor Meiji was a “kami, “ a “deity” perhaps. (“Not a god! and certainly not one with a capitol “G”…)

But the two books were published, and I was invited to join a number of dignitaries (I was the only one not in tails) to bow to the Emperor as he came to the Meiji Shrine to pay respects to the spirit of his grandfather, the Meiji Emperor. The aging Emperor looked a bit startled to see me in the receiving line, but he was told by the Grand Chamberlain, “That one is Harold Wright, the Emperor Meiji translator. The Emperor said something like “Heh?” and nodded politely. I was bowing so low I could only see his shadow and my new shiny shoes.

Emperor Meiji

After publication, Chief Priest Takazawa went around personally to all the two hundred or more embassies in Tokyo. Presenting the books, he requested that the work be translated again into the language or languages of the country involved, and repeated what he had written in the introduction to the first book “. . . in order that people everywhere on earth can appreciate the ‘magokoro’, or ‘pure-heartedness’, of our Emperor Meiji and the global peace for which he strove.”

It wasn’t until I realized he was actually going around Tokyo making this request that I fully understood the deep concern over my translation into English. Many other translators would have to rely on my English for comprehension of the poems. Many would not be able to read the original Japanese, due especially to the grammar and diction of classical poetry. But this “re-translation” is not unusual. Another one of my books, The Selected Poems of Shuntaro Tanikawa, was re-translated into the language of Nepal…

Harold Wright, a poet, renowned translator and retired Antioch College professor of Japanese language and literature. From Ohio to Japan, his life’s work has been a translation of Japanese poetry and at bridging disparate worlds.

Images sourced from Flickr and The Mad Monarchist