Interview by Brian Covert

“Natural farming is more than just a revolution in agricultural techniques. It is the practical foundation of a spiritual movement, of a revolution to change the way man lives.”

—Masanobu Fukuoka, in The Natural Way of Farming

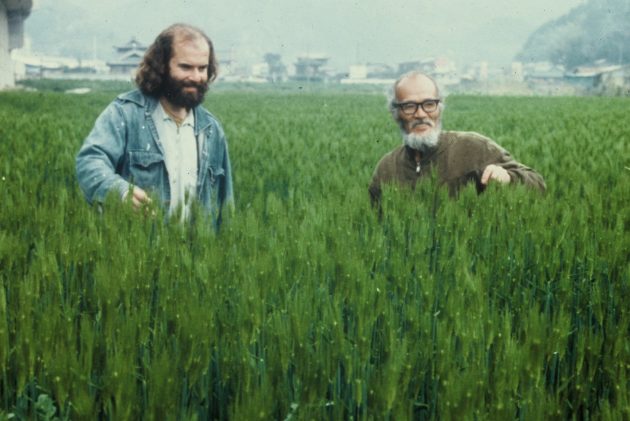

LARRY KORN was a 26-year-old farmhand from the United States living and working at a communal farm in rural Kyoto in 1974 when he decided to go and see for himself an enigmatic farmer-philosopher he had been hearing about through the grapevine in Japan. The buzz among farmworkers was that this farmer was doing remarkable things with his rice, barley and citrus crops in the countryside of Ehime Prefecture on Shikoku, one of Japan’s main islands. Korn, fresh from a stay at a commune on the southern Japanese volcanic island of Suwanose and armed with university studies of plant and soil science in his native California, made his way from Kyoto to the village of Iyo, near the hot-spring city of Matsuyama. There, Korn was met at the rice fields of the Fukuoka Shizen Nōen (Fukuoka Natural Farm) by the farm’s middle-aged proprietor, Masanobu Fukuoka. It was a meeting that would change both of their lives and alter the course of small-scale farming the world over. Fukuoka, by that time, had not plowed his rice fields for a quarter of a century, but was still producing healthy rice crops that could compete with or exceed those of other local farmers in both quality and quantity. Nor did he use any pesticides or artificial composting or do any weeding. “Do-nothing” farming, he called it—following nature’s lead and leaving a minimal human imprint on the earth. Fukuoka credited this type of farming to a revelation he had had back in 1937 at age 25, when he experienced a spiritual vision essentially affirming the sacredness of nature. He soon quit his job as a young inspector of plants at the customs office of the port of Yokohama, and returned to his family’s farm in Shikoku to try and put his divine inspiration to some practical use. Over time, the “do-nothing” method of what Fukuoka came to call “shizen nōhō” (natural farming) was centered around the use of dried straw for ground cover and seed-filled clay pellets for diversifying the crops.

The modest success of his natural farming at that level, as Fukuoka saw it, had the power to heal both the land and the people tending to the land, posing a direct challenge to the destructive practices of modern-day industrial agriculture in Japan and beyond.

Korn ended up staying at that farm for about two years, absorbing the agricultural and philosophical teachings of Fukuoka and coming to understand how his unconventional method of farming in Japan just might benefit farmers elsewhere. Korn decided to return to the U.S. to try to get an English-language version of Fukuoka’s Japanese book Shizen Nōhō — Wara Ippon no Kakumei (Natural farming — the one-straw revolution) printed and released in the United States. The rest is history: the book was published in English in 1978 by Rodale Press as The One-Straw Revolution and became an instant hit, eventually being translated into more than 25 different languages and striking a common chord among local farmers and back-to-the-landers around the globe. Fukuoka now had an international audience with whom he could share his message, and in the years that followed he traveled widely overseas to promote his vision of natural farming in various countries. Fukuoka died in 2008 at age 95.

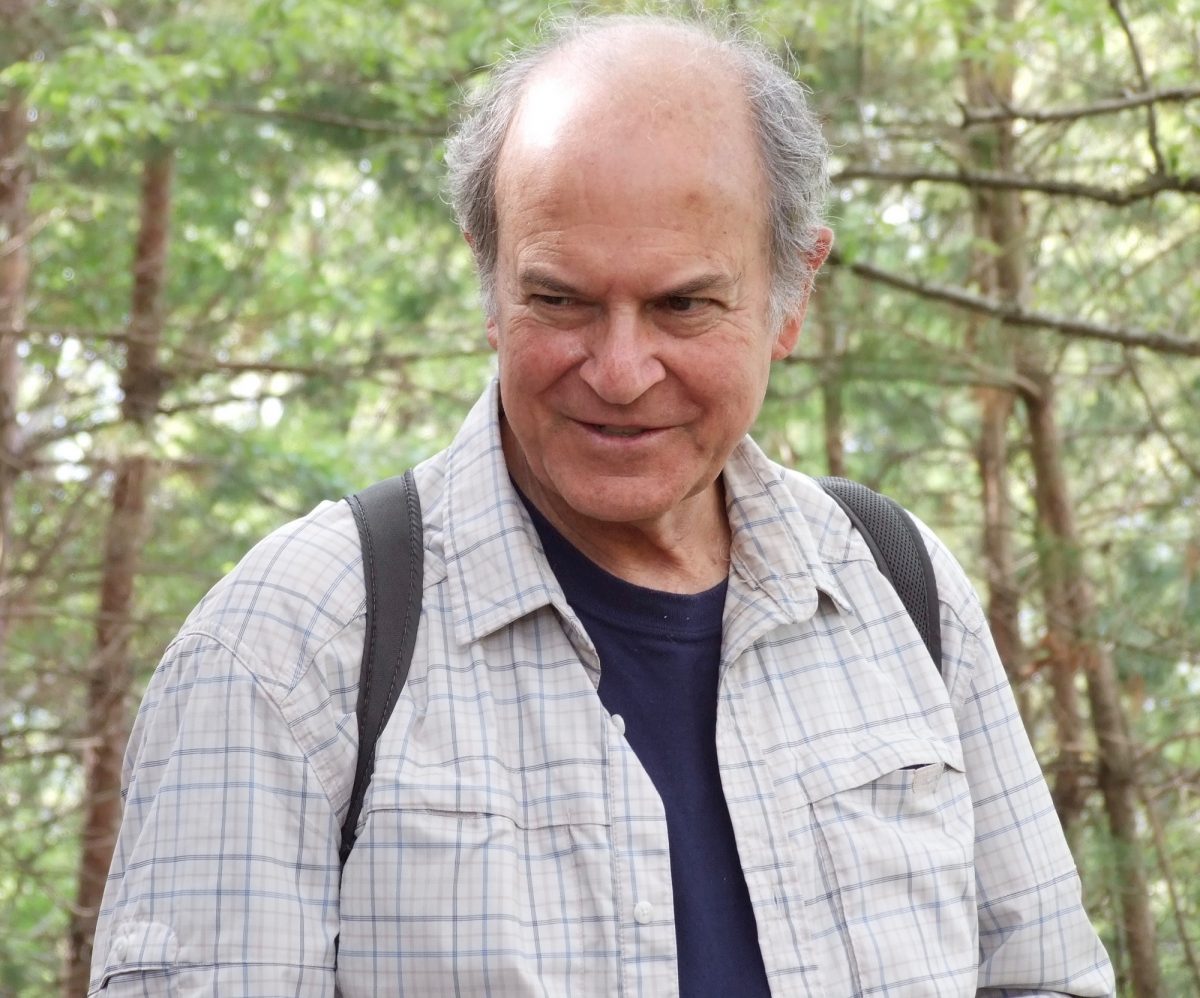

Today Korn is based in the U.S. in Ashland, Oregon and, still referring respectfully to the late Fukuoka by the Japanese honorific of “Sensei,” has devoted the past few years to translating and publishing books to help carry on Fukuoka’s message. Korn regularly lectures and holds workshops in a number of countries where “Fukuoka farming,” as it is commonly known, has taken root and been carried on by yet another generation of small-scale farmers and others pursuing alternative ways of working with the land. Among the events that the 70-year-old Korn already has lined up for 2019 is teaching a class on Fukuoka’s natural farming in Thailand. Korn considers the Fukuoka farming principles and practices he picked up in the 1970s as still relevant to these times—“the only hope,” as he puts it, for the long-term sustainability of the planet.

In spring 2018 Korn returned to the Fukuoka Natural Farm in Japan, completing a circle that began four decades ago in the flatland rice fields and mountainside citrus orchard of Fukuoka’s farm. Journalist Brian Covert recently caught up with Larry Korn at the Yuge dairy farm in Kobe, one of several locations in Japan where Korn was addressing small but receptive audiences and passing along the environmental-spiritual message of his former mentor.

You’ve just come from a tour in India. Tell us a little bit, first of all, about how that went. I understand that Fukuoka-sensei himself thought of India as a place that was carrying forward his vision of “natural farming.”

India was very inspirational for me because I just saw natural farmers everywhere. I taught a seven-day class in Karnataka state, where Bangalore is, and that farm itself was really inspiring. Fukuoka’s orchard [in Japan] had acacia trees and nut trees at the top, at the highest canopy, and then he had various kinds of fruit trees and berries and perennials, and gradually there were all these different layers. And the same layers existed in this farm in India, but the top layer was coconuts, the next layer was papayas and bananas, and then they had many plants that I had never heard of or seen before. It was also no-plowing and keeping a permanent groundcover, and it had so many of the same characteristics [as in Japan]. It was unmistakably Fukuoka-style natural farming.

We saw a number of villagers who came to be part of the course and also taught a little bit of the course, explaining what they do and their rotations. And those farmers, from a group of three villages — 15 to 20 farmers who had been using natural farming for more than 20 years — all said that they got the inspiration from Fukuoka-san and from reading The One-Straw Revolution, specifically. So, that was pretty gratifying for me because when we set out to try to translate that book and get Sensei’s understanding outside of Japan, where it was just languishing, we thought, “If we can just get it translated and published, we’ll get the information outside to the rest of the world.” And they were ready for it: This was in the early ’70s, the environmental movement was just getting started, the back-to-the-land movement, and there was macrobiotic and all sorts of healthy eating. Yoga was coming in.

None of us knew anything about translating or editing or publishing [a book], but we just thought that that would really be a good idea and a helpful thing. And so, 40 years later, to go to India and to find that there’s so many people that were inspired by that book was just really eye-opening, gratifying.

India is also a country with a farming community that has been ravaged by the influx of GMOs and Monsanto and all of that. How do you account for the popularity or the lasting endurance of Fukuoka-style farming in India?

There’s a number of reasons. One of them is that India was doing basically quite well with their small-scale, diversified, village-based farming until the early 1960s, when the “green revolution” came in—which was essentially exporting American-style industrial agriculture, chemical agriculture, to other countries that hadn’t been exposed to it yet. So, that really did a lot of damage in India. They brought in new varieties of crops that needed chemical inputs to continue to yield. They got a slightly higher-than-average yield the first couple of years, then the yields started going down. So, they needed to put in more inputs and then they went into debt for that. It was just devastating to the villages and to the soil, and it created pollution all over. It was bad news.

In the United States and Japan, both countries started with 70 to 80 percent of the people as farmers, and now are down to two or three percent. In India, it’s still 50 to 55 percent of the people still living in the countryside on relatively small-scale farms, and [Fukuoka-style] natural farming is well suited for that.

The biggest difference, I think, is that the Indian people are basically a spiritual people. And the foundation of natural farming is not the specific technique—it’s the way of seeing the world. It’s about getting along in the world, the proper relationship between people and nature. And even more specifically, it’s to help each individual to get back [to nature]. We’ve kind of separated ourselves, as a culture and individually, from nature, and natural farming is a path to get back. Fukuoka-sensei saw that in this “vision” he had when he was 25 years old, and when people couldn’t understand what he was talking about, he went back to his farming village and he created a concrete example, a physical example, by applying the understanding to agriculture.

So, the farming is just an example of seeing the world. And the people in India see the world through the philosophy and so forth first, and then the farming technique second. So, they have a head start. Also, natural farming is so similar to the [nonviolent] approach of [Mahatma] Gandhi, and that approach is still very much alive in India. You just can’t miss the connection there. Sensei himself went to India four times; he met two prime ministers, he was covered on national news when he went there. And even now, natural farmers [in India] are covered in the newspapers all the time.

And yet here in Japan, the birthplace of Fukuoka-sensei, farmers are having a hard time making that transition.

Yeah, after all this time, Fukuoka’s approach is basically being ignored. Japan is still not ready for it, apparently, although they have many of the things that India has: The farms are still small scale, which is ideal for natural farming, and the Japanese are basically a spiritual people that, you would think, might approach natural farming from the philosophy first. But being an individual and just striking out on your own and doing something creative is not something that comes naturally to Japanese, so getting the ball rolling is very hard.

Sensei himself was a free spirit and he did things his way, and that’s not necessarily prized in Japan. He was sort of a pariah in his own village. They didn’t understand him, they pretended that he wasn’t there. He said, “People were not upset with me. They just looked right past me. They pretended I wasn’t there.” Nobody ever asked him what he was doing or asked to get shown around his orchard. But on the other hand, he never went out and volunteered to show people around either. Anyway, natural farming — his style of farming — has not really made inroads in Japan.

Do you see that changing anytime in the future?

I hope so. I see the whole culture [in Japan] changing more towards organic, and a more natural and more healthy way of eating and of living. Whether natural farming will be the basis of that change, maybe not at first. It could gradually find its way there. But I hope that it’ll just start with organic farming: farmers’ markets, where the farmers and the people who are buying the food can meet directly and talk and find that they have common ground. Buying food directly from the farmer is a very good feeling, and it’s also very good economically for both sides.

The super-high cost of natural food in Japan is almost entirely due to the middle-man because there just isn’t that much [on the market] and it’s a chance to take advantage of the consumer. Fukuoka-san, when he was selling his produce, and Kiyoki, his grandson, who is now marketing the same produce, have been committed to keeping the price low because they want the people to see that with natural farming and organic farming, the overhead is much lower, it costs less to produce and the price should be lower. Fukuoka-san, in fact, when he sold his rice or barley or citrus, he told the shopkeeper that he could only mark it up this much. And he actually had people go and check to make sure that they weren’t taking advantage of the consumer because this was very important to him. So, that’s where I see it really starting: the contact between the farmers and the people who are buying the food.

And that was the first step in the United States. When The One-Straw Revolution came out in 1978 in the United States — and coincidentally, permaculture, an organic technique that’s very popular and was created by two Australian fellows [Bill Mollison and David Holmgren], came to the United States exactly at the same time — there were two farmers’ markets in the state of Washington. Now there are hundreds. Every town has at least one farmers’ market. And a city like Portland [Oregon] on a Saturday or Sunday in the summer must have hundreds.

And how many of those organic farmers today are familiar with Fukuoka-sensei and natural farming?

Virtually all of them. The One-Straw Revolution, especially, and all the rest of the work that he did, including traveling to the United States twice [in 1979 and 1986] — the Pacific northwest, California, the northeast and New England is primarily where he went — made him very well known in the United States. I’d say The One-Straw Revolution is probably one of the bestselling books on sustainable agriculture. It has sold probably a million copies by now worldwide. Nobody knows how many languages exactly it’s been translated into, but we’ve counted at least 29 [languages] and eight different dialects in India. When I went to India, they told me it was translated into more like 18 dialects.

“When the farmer forgets the land to which he owes his existence and becomes concerned only with his own self-interest, when the consumer is no longer able to distinguish between food as the staff of life and food as merely nutrition, when the administrator looks down his nose at farmers and the industrialist scoffs at nature, then the land will answer with its death. Nature is not so kind as to forewarn a humanity so foolish as this.”

—Masanobu Fukuoka, in The Natural Way of Farming

You recently went back to the Fukuoka family farm in Shikoku for the first time in almost 45 years. What an emotional reunion that must have been…

This is the first time I’ve been back since I brought the manuscript of The One-Straw Revolution to the United States. The last time I was at the Fukuoka farm [in 1976], people were waving goodbye to me, saying “Good luck, Larry!” and I had my backpack and the manuscript of The One-Straw Revolution rolled up and tucked inside there. So, this is the first time I’ve been back since then.

It was emotional, and it was just fabulous. I got such a warm welcome from the family, and in meeting the other students I lived together with on the farm [in the 1970s]: Tsune Kurosawa, Hide-san, Yu-san and several other people. That’s all been great. I stayed for eight days, and a couple of the days I went out with the farming crew and harvested mikan [citrus fruit], and took them down to the sorting shed. And then I went out and picked shiitake mushrooms. When I was at the farm 40 years ago, Hiroki [Fukuoka’s grandson] was one year old and his mother was carrying him around on her back. Now he’s running the farm, and we got along beautifully. All of that was wonderful, just being back there.

But a lot of things have changed. For example, one of the core components of Fukuoka-sensei’s philosophy was using seed balls to diversify the crops. They’re not doing that at the Fukuoka farm anymore, are they?

No. And even he had slowed down on using seed balls because he didn’t have to use them so much anymore towards the end. He was using them primarily as a way to hide the seeds from birds. He remembered this technique of encasing seeds in clay pellets, which was not his idea — it had been used a lot in farm agriculture in the past — but he revived it and brought it back into the worldwide consciousness.

Not only do [seed balls] protect the seeds from insects and birds, they also provide a little nutrient packet. It helps the seeds to have good conditions when they sprout. When they germinate, they’ve got this little packet of energy that’s right around them. Also, the seeds come up on their own when the time is right. So, Sensei said if you just encase the seeds in pellets and toss them out there, you don’t have to worry about what kind of conditions the different kinds of seeds are in. You don’t have to worry about even what time of year you’re sowing them because nature and the seeds themselves know those things a lot better than you do. So, instead of trying to figure that out yourself, just put the seeds out there and let nature decide which plants are going to come up, and where and when they’re going to sprout. And that was one of the bases of natural farming in general: keeping human decision-making out of the picture. Nature does a much better job. So, he was very happy to follow nature’s lead.

One day he took us up to a place where we could look out over the whole orchard. It was all beautiful, with tall ground cover and diversity of plants—citrus plants growing here and there, pears and apples and pomegranates, and vines going up, vegetables growing everywhere. And he said, “You know, I had nothing to do with designing this garden. Nothing. Well, I made a few terraces, put in a few acacias, built a few huts. But as far as the design of the orchard, what I did was I took the seeds of trees and shrubs and groundcover plants and vegetables and flowers, and I put them all together in seed balls. And I just went around and tossed them all over the place. So, I’m providing the tools for nature, and the design that nature chose is what you see here.” Boy, that was really powerful when he explained it that way. And then I understood why it felt so different to walk in his orchard: It was not a human-designed thing. You’d go in Sensei’s orchard and it was a total, natural free-for-all. It was designed by nature, and there were so many more surprises than when you went into a standard orchard. You’d go out and you’d see something every day that was totally strange and delightful.

So, that was part of the fun. And I don’t know if Sensei wrote about that enough in his writings: how much fun it was to just wake up every morning and walk out into the orchard and go, “Gosh, I wonder what new adventure is going to happen today.” Being alive, really being alive.

His feeling about farming was that even if you’re farming, it doesn’t guarantee that you’re going to be able to find your way back to nature and to living a natural life. You’re outdoors all the time, you’re living with plants and soil, you’re with them and you’ve got yourself as close as possible, but [somehow] you can’t make it happen. And as soon as you forget about rejoining with nature and how frustrating it is not to be able to talk with the grasses and the leaves—Ah! then you find yourself there. And it’s right there.

He also said that natural farming is just one aspect of a broader movement, and that is a natural way of life: You can find your way back to becoming a whole and healthy person and finding an appropriate relationship with nature and other species in a lot of different ways. You can find it there through food or through religion or through art or through yoga or through a lot of different things. And he was focused on the farming. Farming is one way, and there’s a few reasons why he picked it and why he thinks it’s an ideal way, like what I just said: You’re so close [to the natural world]. Also, you’re providing what you need to live. So, in the process of practicing your art or your path of kind of cleaning your act up, with farming you’re also producing food in the process and the other things that you need to live.

As Fukuoka-sensei put it, his way of natural farming was not about cultivating and perfecting crops at all—it was about cultivating and perfecting human beings or the human spirit.

And this is something that the Indian people could see right away: “Oh yeah, I get it.” Because their culture is all designed towards perfecting their personal spirit. And there are certain things that make it a little bit harder [to understand] for westerners, and part of it is that Fukuoka-san explained natural farming through his cultural perspective. He used a lot of Buddhist terms that are familiar to easterners that are not so familiar to westerners, like mu, which translates as “nothingness,” and that really does mean exactly that to westerners. But of course, to an Asian person, it means endless possibilities; it’s so big, it’s the opposite of nothingness, actually.

But westerners are so literal. I’m asked about “no mind” [in Fukuoka’s writings]. Mu and “no mind.” Westerners virtually define themselves by their thoughts: I’m thinking, therefore I exist. So, if you’re not thinking, it’s like mu—nothing, a void. And that makes westerners very uncomfortable. More than uncomfortable: They can’t imagine it. I continued to try to explain natural farming using that angle alone, and I could see people were getting stuck at exactly the same places. Finally, it dawned on me that there was another way of explaining it that westerners were getting more easily, and that was to simply explain that natural farming is what indigenous people were doing all over the world up until just 10,000 years ago. They had a set of ethics that were just about the same for tribes all over the world, but they had to develop a technique for exactly where they lived. In California alone, there are so many conditions in so many places, and the tribes had their own territories and they developed a way of natural farming that was specific to where they lived. Natural farming is not about growing rice and barley and citrus—that’s just the way it looks exactly at Fukuoka’s farm.

That brings up a related point: the difference between organic farming, permaculture and natural farming at a time when “natural” and “healthy”—and even “organic” more and more these days—are little more than advertising copy. How does Fukuoka-sensei’s vision of natural farming differ from those other ways?

All of the other things that you mentioned, including organic farming, permaculture — you could even throw in chemical/industrial agriculture and traditional Japanese agriculture — are all products of the modern culture, after people have decided somehow that we’re better than other species and we’re going to make nature work for us. And since the other species are not as important, we’ll just do what we need for ourselves. And the other species are just going to have to [adapt]. Good luck.

Natural farming is more in line with the way indigenous people lived, which was to observe natural law and to live within a community of species so that we all get along. We need each other to live. We’re all helping each other at the same time. There is also this need that we have to use and eat each other. It’s just the way the world is set up; there’s no value attached to that. It’s just the way it is.

With the indigenous people, it’s more like, “What nature is providing is a gift. We have everything we need.” And there’s a gratitude involved. They take only what they need and they always leave some for other species. They never take it all, and they use everything. There are these ways of living that allowed them to continue living for tens of thousands of years. All the other forms [of farming] are a product of modern culture and it’s more like, “Natural law doesn’t apply to us, so how can we make use of nature?” The industrial farmer says using chemicals is the most efficient way. The organic farmer is using organic additives as the best way to get nature to perform for us.

Permaculture is a kind of ecological form of organic farming, but they’re all about design: They go out to nature and observe what nature is doing. They take some notes and see the patterns. Then they check out the conditions of the soil and begin a soil survey, and do a survey of all the plants. They get all this information together and then they create a design—and they install a design that’s designed after the nature that they’ve observed. So, it’s a design process; it’s completely an intellectual process. It’s the human thinking that the nature they’re observing is digested through their thoughts. It’s kind of an arrogant approach, to my mind. So, the question to them would obviously be: Why not let nature do the design? Like I described, Sensei just tossed the seed balls out and then he walked away, letting nature do the design. Permaculture is a human-driven system, so that’s quite clearly not the same.

You write about how Fukuoka-sensei saw himself as being in service to humanity, trying to tell people that his approach could help solve the problems. Now, decades later, after he talked about the desertification of the state of California and other places, we’re seeing the groundwater running dry and cities facing critical water shortages, among other problems. How accurate were Fukuoka-sensei’s predictions back then?

Oh, he saw clearly the direction that society was going, and the effect that it would have not only on the landscape but also on human lives and culture. You can’t separate the culture from the condition of the landscape. So, he did see that clearly. He was given this inspiration [in the form of a spiritual vision] when he was 25: it was like a bolt from out of the blue; he had no idea why it came to him, but he felt that he had a great responsibility—that he needed to show the world how valuable that could be and that that way of seeing the world could turn the whole ship around. He firmly believed that. And he dedicated each and every day to doing what he could do.

I didn’t realize how committed he was until we traveled together in the United States. He’d always be the first one up, he’d have the tea poured, and as soon as we sat down he wanted to know what the schedule is, like, “What’s the most we can do today to get this going and help?” But towards the end of his life, the last 10 years or so, he could see that it probably wasn’t going to happen during his lifetime, and he became kind of withdrawn and fairly cynical towards the end. It was a shame.

At least some of his hopes are still being kept alive by a small group of loyal, dedicated farmers scattered here and there around the world. Recently, scientists have told us that the planet has entered the sixth mass-extinction age and there’s no going back now. What can something like Fukuoka farming do, if anything, to help turn around such a dire situation?

I think that natural farming, the approach—which is changing our way of thinking to put us back in alignment with the natural world—is the only hope. I’m not depressed or discouraged, though I’m sorry that we’ve gone so far in this direction. But I’m a little bit like Fukuoka: I wake up each day and say, “What can we do? Let’s get moving!” You know, for me, it’s not so much about the farming techniques. It’s about changing minds and attitudes to become more tolerant and compassionate. At least, I think, for a lot of people it’s the entryway, the beginning, of seeing a more appropriate way that we can get along: first with other people and then, finally, with other species.

You know, I used to wake up in the morning and walk out into the orchard [at Fukuoka’s farm], and I would just say hello to my friends, the trees and the plants. I could hear the grasses talking to each other. The trees were kind of saying hello to each other and they’re carrying on conversations. This was just the way it was. You know, I’m not a ditzy person, but this is just the way it was. I could hear all this chatter and it was a joyous thing. And it really did my heart good.

Had you had that experience before you went to Fukuoka-sensei’s farm?

Once or twice, but only briefly. I only had a hint, just a glimpse, and those were at some of these communes in Japan. When I first came to Japan [in 1971], I traveled around to these communes that were really primitive—rustic, let’s call them—places where people were eking out a living the way that people were hundreds of years ago. They were beautiful places, remote places. And you know, I grew up in the city. I grew up in Los Angeles [California, USA] and really had no idea about the natural world. I’d never had a vegetable garden; I didn’t know where food came from. I didn’t know the difference between an evergreen and a deciduous plant: I said, “Deciduous? What does that mean?” And when I lived on these communes, then I had a glimpse.

And I never went back [to the old notions of nature]. From then on, everything I’ve done has revolved around plants and soil. And it started with one experience that I had, where I had been living on a commune on Suwanose island for a couple of months. One night I was just standing out in the fields; it was after dinner, and I was going to walk down to the fields. And the soil started talking to me. Not in words, exactly, but I could definitely feel it. You know, it was a direct personal communication, and I had never experienced anything like that. And it changed my life. Again, everything I’ve done since then has involved plants and soil. And it did kind of prepare me a little bit, just an inkling of that, for Sensei’s farm.

Then you had that experience at the Fukuoka farm, and it opened up a whole new relationship with nature.

Yeah, but one that I couldn’t maintain all the time. Then, after I left the farm [in 1976], I went on my own personal adventure, let’s say, that was not strictly “natural farming.” You know, everybody’s got their personal drama and I lived out mine for the last 10 years. I’ve managed to get back to a place where this is pretty much what I’m doing now. I’m just doing whatever I can to help promote Sensei’s point of view. There aren’t that many people who actually lived at the farm who can explain it and vouch that this place actually existed and how you do it. And also, I knew him personally, so I can help to tell people what he was like as a person. Now I feel the responsibility to keep this going. And it’s something I welcome. I feel like I’m the luckiest person in the world, really, to have had a chance to study with someone like Sensei, first of all, and also have a chance to do something really significant: translate and edit some of his books. So, I’m thrilled to be doing what I’m doing now.

Looking to the future, where do you see Fukuoka-sensei’s message, his legacy, going?

Well, of course, I don’t know. But I’m certainly encouraged by India and Southeast Asia in general, that there’s so much activity there, and I could see those places as becoming places that could demonstrate to the rest of the world how valuable this way of thinking and this way of farming could be. And I think that there is a real opportunity for humanity to see a better way, especially when they’re pushed up against survival. You know, a lot of times people start to make decisions when they really can’t make any other decisions because they’re faced with the alternative, which is not good. So, then they start to see the light.

I’m still optimistic. Sensei said that he is sure that he’s not the first person that’s had this idea [of spiritually based farming]—that this is an idea that’s timeless. And it’s just going to keep coming up. Even if it fades away this time, not being successfully implemented, then it will come again. He said that. He was not attached to things or to legacies.

In fact, the part of the farm where I lived for two years and where we did all of the things that are written about in The One-Straw Revolution and in my book One-Straw Revolutionary, about 15 years before he died, he said, “You know, I wonder would happen if we just stopped doing natural farming here and let nature do whatever it wanted.” And by that, he meant things like keeping the area open to a little more sunlight. When you just stop doing things [with plants and trees], then everything wants the sunlight. And part of the challenge of doing a natural farm or an edible food forest of any kind is to keep enough sunlight coming down to the floor, so that you get a lot of energy and food production at all levels.

So, he said, “I wonder would happen if we stopped.” Now it’s been about 20 years since the family’s done that. And when I went back to the farm [in 2018], it’s unrecognizable now because so many volunteer trees have come up and the existing trees have all kind of closed the canopy above, so it’s much shadier. All the mustard and radish—all the very colorful plants that were along the hillsides—are pretty much gone now. Instead, you’ve got this plant called fuki [Japanese butterbur], a water-loving plant that’s growing all over the hillsides now. It’s gorgeous, but it’s different. The texture is different and it’s growing on the hillsides because there’s so much organic matter in the soil and also there’s no direct evaporation because the canopy is closed on the top, so it feels like it’s in a water-loving place. There’s hardly any citrus there anymore because there’s no sunlight. This is just the way things evolve, and this is what Sensei requested.

The huts are all starting to collapse and be abandoned; the place where I lived is not there anymore. And he welcomed this. When I walked on the farm in this condition [recently], I would not have recognized it as being a farm. I got a really nice feeling from it. The plants were very happy, and it was easy still to talk to them. They were just singing a different song. And it was a song of moving on, like all things do: they come into existence and they flower and then they go out of existence and more are coming into existence all the time. It’s mainly an Asian concept, a timeless concept—no linear time, just this thing that’s existing. That’s the way the world is.

So, I don’t think he was attached to an outcome, personally. But he sure fought hard to try to save this version of humanity or this version of creation.

How successful do you think he was in his lifetime, all things considered?

The number of people practicing natural farming or even organic farming is still tiny now, compared to where the main culture is going. So, in that sense, I don’t think he was that successful. But as far as changing the lives of individuals and individual communities, he was completely successful with the ones that heard the message. They’re forever grateful, I’m forever grateful, to him. My life is so much richer and feels more complete for having come in touch with Sensei and, even more importantly, the message. I’m just a communicator—Sensei was a teacher, clearly, but he was saying, “It’s not about me, it’s about the message I received. I’m just a farmer.” And really, that’s how all of us who studied directly from him [learned it]. It’s the message that’s the important thing.

Further reading & viewing:

Masanobu Fukuoka, Shizen Nōhō — Wara Ippon no Kakumei [original Japanese edition of The One-Straw Revolution], Shunjusha, Tokyo, Japan, 2010.

Masanobu Fukuoka, The One-Straw Revolution — An Introduction to Natural Farming [translated English edition], New York Review Books, New York, USA, 2009. Edited by Larry Korn.

Masanobu Fukuoka, Sowing Seeds in the Desert: Natural Farming, Global Restoration, and Ultimate Food Security, Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, Vermont, USA, 2012. Edited by Larry Korn.

Masanobu Fukuoka, The Natural Way of Farming: The Theory and Practice of Green Philosophy, Bookventure, Madras, India, 2006 edition. Translated by Frederic P. Metreaud.

Masanobu Fukuoka, The Road Back to Nature: Regaining the Paradise Lost, Bookventure, Madras, India, 2011 edition. Translated by Frederic P. Metreaud.

Larry Korn, One-Straw Revolutionary: The Philosophy and Work of Masanobu Fukuoka, Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, Vermont, USA, 2015.

Fukuoka Masanobu Shizen Nōen [Masanobu Fukuoka Natural Farm], official website, Iyo, Ehime, Japan.

Patrick Lydon and Suhee Kang, directors, Final Straw: Food, Earth, Happiness, documentary film, 2015.

BRIAN COVERT is an independent journalist, author and educator based in western Japan. He has worked for United Press International (UPI) news service in Japan, as a staff reporter and editor for English-language daily newspapers in Japan, and as a contributor to Japanese and overseas newspapers and magazines. He currently teaches journalism at Doshisha University in Kyoto.

Photos by Tsune Kurosawa, Larry Korn, Brian Covert